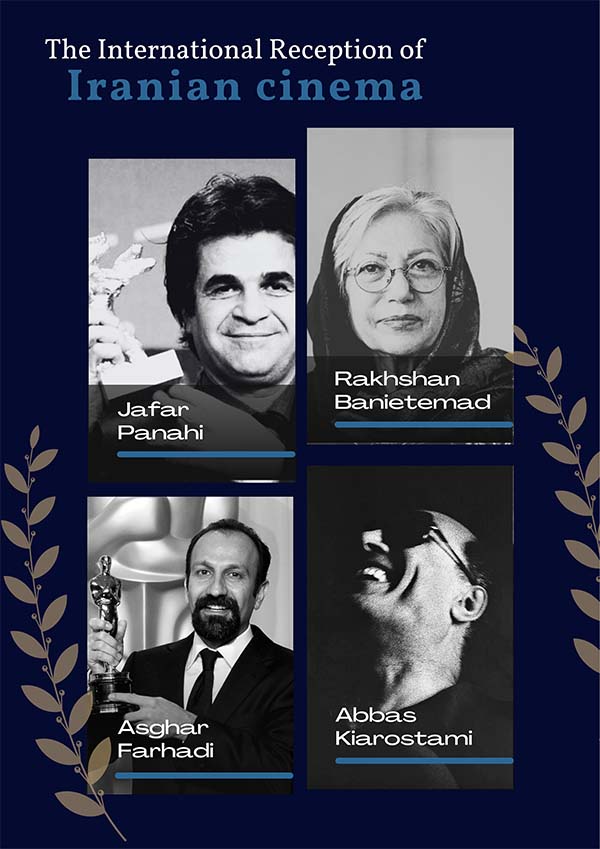

The International Reception of Iranian Cinema

Introduction

Iranian cinema entered the European film festival scene in the 1960s.1Roy Armes, Third World Filmmaking and the West (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987), 191. The first Iranian film to screen at Cannes was Mostafa Farzaneh’s Cyrus the Great (1961) during the year of its release. Viewed retrospectively, perhaps of more significance was Forough Farrokhzad’s The House is Black (1962), a twenty-one minute documentary, the length of which belies its importance. It won a Grand Jury Prize at the Oberhausen Short Film Festival in 1963 and has been cited as seminal by filmmakers and critics from Mohsen Makhmalbaf to Jonathan Rosenbaum.2Jonathan Rosenbaum, review of The House Is Black by Forough Farrokhzad, Chicago Reader (March 7, 1997), jonathanrosenbaum.net February 22, 2021/ Accessed June 24, 2022, jonathanrosenbaum.net/2021/02/the-house-is-black/. Some trace the origins of the Iranian New Wave to around this time, although Parviz Jahed claims it as around 1969.3Parviz Jahed, “The Forerunners of the New Wave Cinema in Iran,” in Directory of World Cinema: Iran. ed. Parviz Jahed (Bristol: Intellect, 2012), 84–91. By 1979 a number of major films had been selected for the European A festivals including Darius Mehrjui’s The Cow (1969), which famously debuted internationally at Venice in 1971 without subtitles. The Berlinale introduced both Sohrab Shahid Saless and Parviz Kimiavi in 1974 and 1975 respectively, while Cannes responded with international premieres from Bahman Farmanara and Bahram Beyzai, setting up a triangle between the two European festivals and Iran that would be resumed decades later. Just when Iranian cinema seemed to be blooming, the Islamic Revolution struck. There was a huge decline in production just before it, and immediately following it a virtual standstill.

Figure 1-2: Left: Movie poster for The House is Black (1962), Forough Farrokhzad. Right: Movie poster for The Cow (1969), Darius Mehrjui

This entry, concerned with the international reception of post-revolutionary cinema, will trace the history of the latter’s early reception through to its establishment as an important national cinema concluding with the winning of Iran’s first Academy Award in 2012. The markers for this will be festival screenings, because “festivals and critics grew the commercial market for Iranian films abroad.”4Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema volume 4: The Globalizing Era 1984-2010 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012), 246. Cinema and politics are generally acknowledged as being closely connected in Iran and this is very pertinent to its international reception. The brevity of this article prevents much exploration of these connections. However, while focusing on the FIAPF A list festivals, it does devote some consideration to the audience-driven Rotterdam International Film Festival in order to demonstrate the impact of geopolitics. It then turns to a discussion of the other, various reasons for Iranian cinema’s international appeal, considering factors such as aesthetics and content. It will conclude with an overview of the post-Ahmadinejad period.

After the Revolution

Following the Islamic Revolution there was very little film production until the establishment in 1983 of the Farabi Cinema Foundation (Farabi), tasked with all matters cinematographic, from production to international affairs. As discussed by Mohammad Attebai, who worked at Farabi in the 1980s, initially Farabi staff persistently sent out letters and screeners to the major international festivals to no avail.5Interview with the author, February, 2011. The first film screened internationally after the Revolution was Amir Naderi’s The Runner (1985), at Nantes in 1985 where it was awarded a prize. The following year it screened at the London and Sydney film festivals, and in 1987 at a further three festivals. Alireza Shojanoori, then in charge of the international arm of Farabi, has singled out the screening of Frosty Roads (dir. Maud Jafari Jozani) at the 37th Berlinale in 1987 as what he considers the first major “international attention” having been paid to post-Revolutionary Iranian cinema.6Alireza Shojanoori, Interview with the author, 16 February, 2011. Frosty Roads then screened at Montreal, Tokyo and Hawaii as well as Hong Kong alongside The Runner. Mohsen Makhmalbaf began his foray into the international scene in 1988 when The Peddler was screened at the London Film Festival.

Figure 3-4: Left: Movie poster for The Runner (1985), Amir Naderi. Right: Movie poster for The Peddler (1986), Mohsen Makhmalbaf.

Perhaps the year when real international success for the cinema of the Islamic Republic might be considered to have begun was 1989. The Iran-Iraq War had ceased in August 1988 and in June 1989 the Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini passed away. Both events had an impact on cinema but of more immediate impact was the screening of Kiarostami’s Where is the Friend’s House? at the forty-second Locarno International Film Festival held that same year. Made in 1986 and first screened at Nantes in 1988, this first of Kiarostami’s Koker trilogy received a “modest” Bronze Leopard and four other awards at Locarno, not yet a FIAF A list festival, but nonetheless a major one. Azadeh Farahmand specifically attributes the “escalation in the presence of Iranian films abroad” to Kiarostami’s Locarno success7Azadeh Farahmand, “Perspectives on Recent (International Acclaim for) Iranian Cinema,” in The New Iranian Cinema: Politics, Representation and Identity. ed. Richard Tapper. (London: Taurus, 2002), 94. and Naficy records a sudden leap in international exhibition in 1990, with “230 films in 78 international festivals, winning 11 prizes.”8Hamid Naficy, “Islamizing Film Culture in Iran: A Post-Khatami Update,” in The New Iranian Cinema: Politics, Representation and Identity. ed. Richard Tapper. (London: Taurus, 2002), 51. Around 1991 the National Film Archive of Iran assembled a collection of sixteen international award-winning films, which it made available as 16mm prints for festivals and cultural events internationally. Distributed by Farabi under the banner, “Festival of Iranian Films,” this highly successful venture resulted in events right around the world. (In Australia, for example, the festival screened in Sydney and Melbourne under the aegis of the Australian Film Institute.)

At this point it is important to note that what is seen internationally, and thus what is discussed here, is generally labelled under the category of “festival films” and accounts for a very small percentage of the total Iranian film output. Films generally approved and considered desirable for the domestic market include commercial comedies, sacred defence films and social issues films. The pan-Islamic market assumed a priority during Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s second presidential term. The results of the ensuing government productions, starting with Shariar Behrani’s Kingdom of Solomon (2009), were not successful. However mention should be made of Majid Majidi’s Islamic blockbuster Mohammad, Messenger of God (2015), made with a crew heavy with Oscar winners such as cinematographer Vittorio Storaro and composer A.R.Rahman. It did gain some international traction despite facing controversy in some Islamic countries.

Figure 4-5: Left: Movie poster for Where is the Friend’s House? (1986), Kiarostami. Right: Movie poster for Mohammad, Messenger of God (2015), Majid Majidi.

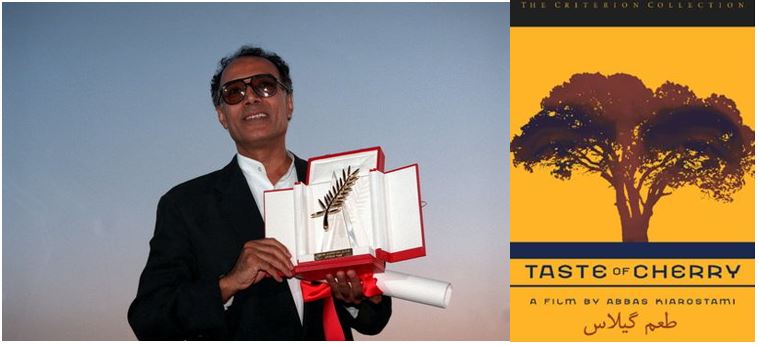

Returning to Kiarostami, Through the Olive Trees, the third film in his Koker trilogy, was nominated for a Palme d’Or at Cannes in 1994, marking the beginning of what would be known as the ‘golden era’ of Iranian cinema. By 1997, when The Taste of Cherry won the Palme d’Or at Cannes, France alone had already honoured Kiarostami with the Career Award of the Prix Roberto Rossellini at Cannes (1992), and made him an Officier de la Légion d’honneur (1996). However, Locarno had also continued to acknowledge Kiarostami. In 1995 Marco Müller presented the first ever “virtually complete” retrospective of Kiarostami’s films at Locarno, along with an exhibition of his photographs of landscapes and two paintings.9Jonathan Rosenbaum, “From Iran with Love.” Chicago Reader, 29 Sep. 1995: jonathanrosenbaum.net accessed 12 Oct. 2012.

But Locarno’s contribution to Iranian cinema was greater than this. Müller was the first to screen Tahmineh Milani’s debut feature, The Legend of Sigh, in 1991; and under his directorship, two classics of New Iranian Cinema came to world attention with Golden Leopards: Ibrahim Foruzesh’s The Jar, in 1994, and in 1997 Jafar Panahi’s The Mirror. In 1998 Müller invited Abolfazl Jalili to Locarno where he received Locarno’s Silver Leopard for Dance of Dust.

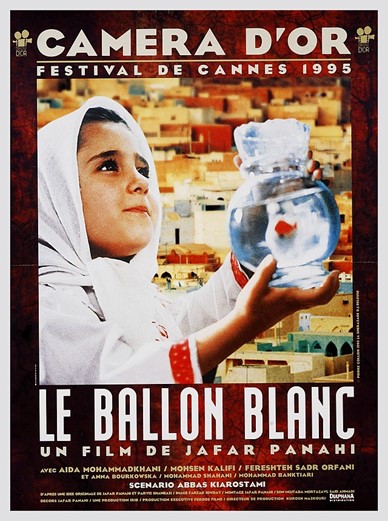

Festival interest continued to build, along with limited commercial interest. International awards proliferated from 1995 with Panahi’s 1995 Camera d’Or (Cannes) win, The White Balloon, followed in 1998 by his above-mentioned Golden Leopard for The Mirror. Majid Majidi had been represented in the Director’s Fortnight at Cannes back in 1992 with his directorial debut, Baduk. In 1997 his Children of Heaven (1997) was the first, and for long the only, Iranian film nominated for Best Foreign Film at the Academy Awards. By the late 1990s, “No respectable festival could be without at least one film from Iran.”10Richard Tapper, “Screening Iran: The Cinema as National Forum.” Global Dialogue, 3:2–3 (2001): 120-31.

Figure 5-6: Left: Movie poster for Taste of cherry (1986), Kiarostami. Right: Kiarostami at the Vienna Film Festival with the Palme d’Or

Iran—A Millenium Hotspot

In 2000 Hamid Dabashi made the witty comment that, “for reasons that have nothing to do with the dawn of the third millennium, because Iran follows its own version of the Islamic calendar, the year 2000 marks a spectacular achievement for Iranian cinema.”11Hamid Dabashi, Close Up: Iranian Cinema, Past, Present, and Future (London: Verso, 2001), 259. Three early career Iranian filmmakers won major awards at Cannes—Samira Makhmalbaf won a Special Jury Prize for Blackboards, and the Camera d’Or was shared by Hassan Yektapanah (Djomeh) and Bahman Ghobadi (A Time for Drunken Horses). Most importantly, their films were all purchased for international distribution. Even more successful internationally, but more controversial on the home front, was Jafar Panahi’s The Circle which won a Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival later that year and received wide international distribution. This exceptional achievement for Iranian cinema internationally was a kind of spring following the 1997 election of a Reformist government.

Yet another landmark, very important for the reception of Iranian cinema, also occurred in 2000—the first prominent use of the term ‘The New Iranian Cinema’ to describe a series of film screenings, and concurrent conference in London, followed by the seminal book of the conference papers, published in 2002. The New Iranian cinema was now a movement.12

In 1999 the National Film Theatre, London, presented a season, titled “Art and Life: The New Iranian Cinema”, and consisting of some sixty films, both pre- and post-revolutionary, accompanied by a small catalogue of the same name. The papers of the concurrent landmark were drawn together by Richard Tapper in the seminal book, The New Iranian Cinema: Politics, Representation and Identity.

However a very different, non-filmic landmark was created with 9/11. September 11, 2001 was a major turning point for many festivals. While up to that point festivals were focused on aesthetics, suddenly ideology and relevance became important. Many programmers who had seen objectivity as important in programming suddenly felt compelled to take a position in relation to the horrific rise of Islamophobia internationally.

Figure 7-8: Left: Movie poster for Blackboards (1999), Samira Makhmalbaf. Right: Movie poster for The Circle (1999??), Jafar Panahi.

The International Film Festival Rotterdam—A Case Study

Just four months after the September 11 attacks, the International Film Festival Rotterdam (IFFR), a large audience-driven festival with only a small market and a modest yet important production fund, demonstrated its serious political engagement. The co-directors, Simon Field and Sandra den Hamer, wrote in the introduction to the catalogue:

We are … presenting the festival in a world that has been rocked by September 11 … And in this world the question of ‘what cinema’ takes on additional force. Is there now an even more urgent need for a socially responsible cinema, for a new political cinema? In this regard, we strongly believe that a festival like Rotterdam becomes even more important as a necessary platform: showing films from different cultures and different perspectives and as a meeting place for people from all over the world.13Catalogue 2002, 23 January-3 February: 31st International Film Festival Rotterdam 2002, ed. Lot Piscaer (Rotterdam: International Film Festival, 2002), 12.

IFFR’s traditional engagement with Iran saw the integration of an unprecedented nine Iranian films across the programme that year. Peter van Hoof, programmer of a section called The Desert of the Real wrote a segment introduction in rhetoric reminiscent of the IRI itself:

The Film Festival Rotterdam was originally for many a cultural and ideological breeding ground where ‘politics’ and ‘cinema’ were inextricably bound up with each other. Film was a weapon in the struggle against imperialism and class struggle, and the aim of awakening a political consciousness. People took up arms against the dominance of Hollywood: its dominant film language, financial colonialism and repressive tolerance. Ideologies such as socialism, liberalism and nationalism have made way for more realistic and pragmatic varieties of capitalism …. Western cinema follows meekly [sic].14Catalogue 2002, 13.

Milani’s The Hidden Half, Rakshan Bani-Etemad’s Under the Skin of the City (a Farabi production) and Majid Majidi’s Baran, Kiarostami’s A.B.C. Africa and Reza Mir-Karimi’s Under the Moonlight were screened. Another three inclusions in the programme had been recipients of funding from IFFR’s Hubert Bals Fund. These were Secret Ballot, a first film directed by Babak Payami and produced by Marco Müller while he was at Locarno, that had won an award for screenplay at Venice in 2001; Delbaran, from the (then) mid-career director Abolfazl Jalili who had been one of IFFR’s Filmmakers in Focus the previous year; and Killing Rapids from veteran filmmaker Bahram Beyzai. The whole selection is notable for its diversity.

Iranian cinema remained prominent in the IFFR programme. In 2006 they introduced a segment called “hotspots,” the intention behind which was explained as follows: “To discover specific filmmakers and audiovisual artists, we are looking for the particular environment in which their work originates, the local scene.”15Kies Brienen, “Hot Spots,” in Catalogue: 36th International Film Festival Rotterdam. 2007, n.p. Iran featured in that first year with twenty short films, documentaries about cinema, music and Tehran, along with features, including Rafi Pitts’s It’s Winter and Jafar Panahi’s Offside in the general programme. The well-known musician, Mohsen Namjoo, gave his first performance outside Iran.

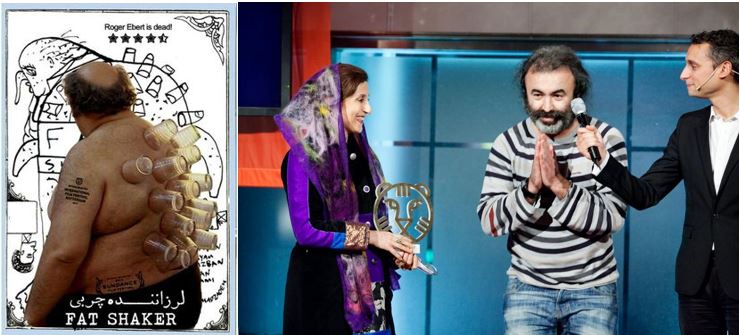

Iran has had some success in IFFR’s Tiger Awards Competition, which focuses on “promoting young talent in filmmaking from around the world”16IFFR Official Website, 2012. with Ramtin Lavafipour’s Be Calm and Count to Seven (2009). In 2013 Mohammad Shirvani’s Fat Shaker (2013) shared the award with two other films under a jury that included the famous Iranian actress Fatemeh Motamed Arya and Chinese artist/activist Ai Weiwei. At least equally significant was the festival’s Hubert Bals Fund for cinema from developing countries, where Iranian filmmakers received hefty funding support over the years. Moreover, the festival hired a specialist on Iranian and Arab cinema and art, the London-based independent curator, Rose Issa, to IFFR.

IFFR’s promotion of Iranian cinema internationally is more important than it might appear. Although Rotterdam prides itself on the size of its local audience, it also attracts many international film programmers, giving rise to Jafar Panahi’s description of the festival as a “souk”, despite there being no official market at Rotterdam.17Parviz Jahed, “Independent Cinema and Censorship in Iran: Interview with Jafar Panahi,” in Directory of World Cinema: Iran, ed. Parviz Jahed (Bristol: Intellect, 2012), 15. The festival’s reputation for quality programming ensures that most films screening there would travel, and widely, perhaps to festivals that may select only one or two Iranian films in any year.

Figure 9-10: Left: Movie poster for Fat Shaker (2013), Mohammad Shirvani. Right: Shirvani is receiving an award from Motamed-Aria at the Rotterdam Film Festival.

The Contradictory Politics of Film Festivals

The response or lack of it to the September attacks by the various festivals suggests “the contradictory politics of film festivals” that Farahmand had already noted in 2000.18Farahmand, “Perspectives” 104. A line was drawn between big market-driven festivals and festivals aimed at the general public, shocked into acknowledging contemporary politics in their programmes. This spike in interest from 9/11 did not last. Panahi noted in an interview in early 2008 that Iranian cinema was experiencing a decline in representation internationally.19Parviz Jahed, “Independent Cinema and Censorship in Iran,” 18.

Although initially the larger festivals were not concerned to take any kind of public political stance in relation to Iran, maintaining instead their focus on cinematic excellence, this changed radically in 2010 with Panahi’s arrest. Suddenly Cannes and the Berlinale competed with each other to show their commitment to the rights of filmmakers. In 2010 Cannes left an empty chair on the jury for Panahi; images of Juliet Binoche weeping at the news that Panahi had begun a hunger strike flooded the media, and Panahi was awarded the Carrosse d’or (Golden Coach) Prize, an annual tribute for the innovative qualities, courage and independent-mindedness of a filmmaker’s work. The Berlinale repeated the performance in 2011 with another empty jury chair. Jury president Isabella Rossellini read an open letter from Panahi at the festival opening ceremony, and festival director Dieter Kosslick continued to note his absence throughout the festival, whilst a truck circled the Potsdamer Platz, the festival venue, with a signboard asking, “Wo bleibt Jafar Panahi” (Where is Jafar Panahi?). A few months later Cannes screened Panahi’s This Is Not a Film (made despite his having been banned from filmmaking, and ostensibly smuggled out of Iran on a USB stick inside a cake).

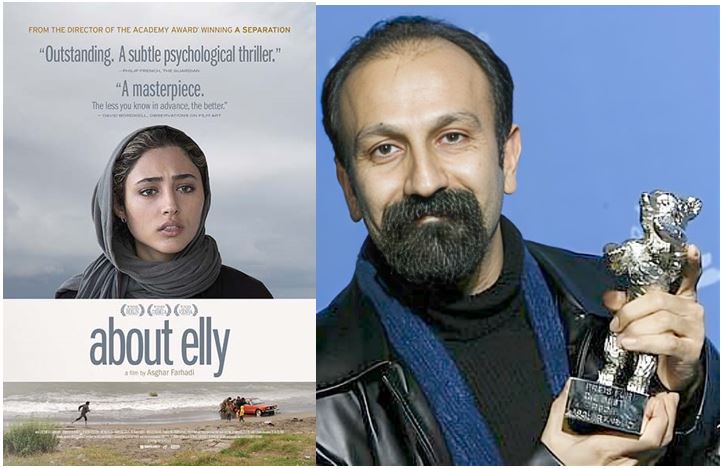

Viewed retrospectively, Panahi’s 2008 concern about a decline in representation seemed unjustified and perhaps the Berlinale triumphed over Cannes—in 2009 they had backed Asghar Farhadi’s About Elly, which won a Silver Bear for best director. After Farhadi’s next film, A Separation, won the Golden Bear the following year, it was picked up by Sony Pictures Classics. Such a major distributor was able to mount the Oscar campaign necessary for a chance to win an award and, subsequently, in 2012, A Separation became the first Iranian film to win an Academy Award (for Best Foreign Film). Iran was now a real “player” and could anticipate increased commercial success.

Figure 11-12: Left: Movie poster for About Elly (2009), Asghar Farhadi. Right: Farhadi which won a Silver Bear for best director

Figure 13-14: Left: Movie poster for Separation (2011), Asghar Farhadi. Right: Farhadi’s Separation won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 2012

The Cannes /Berlin rivalry surfaced again in 2013, when Cannes world-premiered Farhadi’s The Past and Rasoulof’s Manuscripts Don’t Burn, while Berlin screened Panahi’s Closed Curtain, rumoured to have been rejected by Cannes. Would it be cynical to note the extensive publicity this generated for both festivals?

Rotterdam had continued its commitment to Iranian cinema and in 2013 presented a special focus of thirty-six shorts and features, Signs—Inside Iran, with an emphasis on underground and exilic work. There were three features from well-known directors: A Modest Reception (Mani Hagighi), which had premiered at Berlinale the previous year, and two exilic works, Makhmalbaf’s The Gardener (2012, at the Busan International Film Festival), and Bahman Ghobadi’s Rhino Season. But even Rotterdam had not avoided exoticism. The notes by the curators indicated that in preparing the programme, both had visited Iran for the first time. Taal’s comments, published as “Imprisoned in an Unwanted Vacation,” read like an exotic traveller’s tale.20Bianca Taal and Gertjan Zuilhof. “Signals: Inside Iran: An introduction,” in International Film Festival Rotterdam, 19 Jan. 2013. https://iffr.com/en/blog/signals-inside-iran-an-introduction-by-bianca-taal-and-gertjan-zuilhof Accessed 15 Apr. 2013.

Moving to North America, in 1995 the prestigious Telluride Film Festival had opened with Jafar Panahi’s Camera d’Or winner, The White Balloon, where Werner Herzog introduced it with the following statement: “What I say tonight will be a banality in the future. The greatest films of the world today are being made in Iran.”21Dorna Khazeni. “Rev. of Close Up: Iranian Cinema Past Present and Future, by Hamid Dabashi.” Bright Lights Film Journal, 35 (2002). https://brightlightsfilm.com/book-review-close-hamid-dabashi/#.YrV7aS2r2Aw Accessed 15 July 2013. Often films which had missed a premiere at one of the European A festivals were held back for the Montreal World Film Festival (WFF) in late August or for the Busan International Film Festival (now known as BIFF, and previously as the Pusan International Film Festival), early October which was preferred over WFF by at least one sales agent.22Email correspondence with Mohammad Atebbai. It is notable that Iranian filmmakers had the power to decide on their premieres. However, WFF had a solid record for attracting premieres. WFF president Serge Losique noted of Jafar Panahi’s appointment as Head of the Jury in 2009, that “the appointment fits the festival’s long history of championing Iranian cinema.”23Denis Seguin, “Iranian Director Jafar Panahi to Lead Montreal’s Competition Jury,” Screen Daily, 18 Aug. 2009. https://www.screendaily.com/iranian-director-jafar-panahi-to-lead-montreals-competition-jury/5004645.article. 5 Nov. 2010 Majidi’s aforementioned The Children of Heaven (1997) won WFF’s top award, the Grand Prix of the Americas, in 1997, before its nomination for an Academy Award. Majidi loyally returned with The Color of Paradise (1999) and Baran (2001), each of which also took the award. Leila Hatami and Fatemeh Motamed Arya have both received Best Actress awards there. The Toronto Film Festival has also screened its share of Iranian cinema, including the world premiere of Bahman Ghobadi’s Rhino Season (2012). The New York Film Festival and the Lincoln Center under Richard Pena also showed a substantial commitment to Iranian cinema in the form of retrospectives.

Figure 15-16: Left: Movie poster for The Color of Paradise (1999), Majid Majidi. Right: Movie poster for Children of Heaven (1997), Majid Majidi.

Iranian cinema has been embraced by many major Asian festivals (such as Busan, Hong Kong, and Kerala) ideologically concerned to combat the exoticization of Asian film. They encourage Asian filmmakers to resist the lure of the West, in terms of adapting style or content to Western taste, and encourage preferencing Asian premieres. Already in 1989 the Hong Kong International Film Festival, arguably the major Asian festival at the time, screened The Peddler (dir. Mohsen Makhmalbaf) and Frosty Roads (dir. Massood Jafari Jozani).

BIFF, which was established in 1996, and quickly became the premiere Asian festival, has accorded Iranian cinema significant representation and recognition in the various sections of the programme since its inception. The Fipresci Award has twice in the period from 2000 to 2013 been won by an Iranian film—Parviz Shahbazi’s Deep Breath (2003) and Mourning (2011), directed by Morteza Farshbaf—and three times in that same period, the New Currents Award has gone to a new Iranian director: Marziyeh Meshkini, for The Day I Become a Woman (2000), Alireza Armin,i for Tiny Snowflakes (2003), and Morteza Farshbaf, for Mourning (2011). Mohammad Ahmadi’s Poet of the Wastes received the CJ Collection Award in 2005. In 2003 Makhmalbaf accepted the first annual Filmmaker of the Year Award, concurrent with a retrospective of his work. Makhmalbaf (in 2007) and Kiarostami (in 2010) have been appointed Dean of Busan’s annual Asian Film Academy programme and Iranian filmmaker and scriptwriter, Parviz Shahbazi was Directing Mentor in 2012.

The International Film Festival of Kerala’s (IFFK) distinctly Third Cinema programming regards its intended audience as local, but it has international impact among Asian cinema cinephiles. It has had a strong commitment to Iranian cinema, and Iranian guests and jury members have included Kiarostami, Panahi, Fatemeh Motamed Arya, Niki Karimi, Mania Akbari, Samira Makhmalbaf, and Mohammad Rasoulof.

The latter part of this time period also witnessed the rise of the Iranian themed film festival model. These targeted largely the Iranian diaspora but have also broadened the appeal of Iranian cinema.

The International Appeal of Iranian Cinema

Festival programmers, in their rush for the new, can be fickle; and the duration of a hotspot may be short. It is fruitful to explore some of the reasons for the ongoing appeal of Iranian cinema. Its prominence in Western festivals since the 1990s has waxed and waned and coincided with two contradictory situations. The first, the ongoing topicality of Iran’s domestic and international political situation, has already been discussed. This has combined with a changing festival landscape, one with a demand for an increased number of soft arthouse films; a requirement for novelty and exoticism are important elements in the rise of any hotspot.

Hamid Naficy has noted that Iranian cinema is “counterhegemonic politically, innovative stylistically and ethnographically exotic.”24Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, vol. 4, 176. This combination has allowed it to pass the festival gatekeepers, as ideal festival material, appealing to a broad demographic. Naficy notes more explicitly that this cinema embraces “small and humanist topics” and “often deceptively simple but innovative styles.”25Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, vol. 4, 175.

In 2001 Richard Tapper had perceived its appeal as follows:

Iranian movies have drawn international attention by their neo-realism and reflexivity, their focus on children and their difficulties with the portrayal of women. In an age of ever-escalating Hollywood blockbusters, part of their attraction [like that of much ‘Third World’ cinema] comes from shoestring budgets and the use of amateur actors. Many successful films have had strikingly simple, local, small-scale themes, which have been variously read as totally apolitical or as highly ambiguous and open to interpretation as being politically and socially critical.26Tapper, “Screening Iran.”

Jafar Panahi’s The White Balloon (1995; Camera d’Or Cannes), perhaps the most widely known of the “Children Cinema” films, epitomizes this, as its Variety review indicates: “By turns suspenseful and amusing, deceptively slight tale is a charmer with lots of local color.”27Lisa Nesselson, review of The White Balloon by Jafar Panahi, Variety, May 31, 1995. https://variety.com/1995/film/reviews/the-white-balloon-1200441531/#! Accessed 28 June 2022.

Laura Mulvey emphasized the aesthetic a year later, in 2002, writing that “there is no point in denying an element of the exotic in attraction between cultures,” but the attractiveness for non-Iranian audiences to “the sense of strangeness … is just as much to do with an encounter with a surprising cinema as with the screening of unfamiliar landscapes and remote people” ….and “[t]he exotic alone cannot sustain a ‘new wave.’”28Laura Mulvey. “Afterword,” in The New Iranian Cinema: Politics, Representation and Identity. ed. Richard Tapper (London: Taurus, 2002), 256. Here there is acknowledgement of a cinema of quality that has indeed sustained. In the following year Chaudhuri and Finn (2003) also countermanded the appeal of the exotic as the overriding factor in the appeal of Iranian cinema. They suggested that the “appeal of New Iranian Cinema in the West may have less to do with ‘sympathy’ for an exoticised ‘other’ under conditions of repression than with self-recognition. The open images of Iranian film remind us of the loss of such images in most contemporary cinema, the loss of cinema’s particular space for creative interpretation and critical reflection.”29Shohini Chaudhuri and Howard Finn, “The Open Image: Poetic Realism and the New Iranian Cinema.” Screen 44 (2003), 38.

Figure 17: Movie poster for The White Balloon (1995), Jafar Panahi.

These arguments are supplemented by other, more general ones. Films are seen as direct sources of information about countries, unmediated by Western (or any) media. They also offer escapism in the form of pleasurable armchair travel with location/culture foregrounded, education in the broad sense and an alternative perspective or truth. They are therefore often regarded as more accurate or more evocative. The filmmaker’s eye is seen as a superior substitute for the tourist’s own eye, one that gives a more vivid and/or accurate account of historical or current events. The well-known curator Rose Issa, on her choice of Iranian films for the 2006 Berlinale, commented that, “All the current issues of daily life in Iran are reflected in their [Rafi Pitts’s and Jafar Panahi’s] work. Those who go and see the films will have a better view of what life is like in Iran today.”30Ray Furlong, “Iran Films Return to Berlin Festival.” BBC News, 18 Feb. 2006. accessed. 29 Dec. 2010. Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa commented similarly:

One of the attractive elements of Iranian films for non-Iranian audiences abroad is the locations used. On a safe, visa-free tour they can ‘visit’ parts of Iran and construct a mental map of the country and its culture. At times, watching these films confirms pre-existing images of the place as an exotic land of mystery (ancient mythical Persia) and misery (terrorism and poverty).31Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa, “Location (Physical Space) and Cultural Identity in Iranian Films,” in The New Iranian Cinema: Politics, Representation and Identity, ed. Richard Tapper (London: Taurus, 2002), 200–201.

Mohsen Makhmalbaf was well aware of the appeal of exoticism when making Gabbeh. According to the Makhmalbaf Film House website, Gabbeh “served both as artistic expression and autobiographical record of the lives of the weavers. Spellbound by the exotic countryside, and by the tales behind the Gabbehs, Makhmalbaf’s intended documentary evolved into a fictional love story which uses a gabbeh as a magic story-telling device weaving past and present[,] fantasy and reality.” The film was “one of the top ten films of the year,” according to Time magazine.

Figure 18: Movie poster for Gabbeh (1996), Mohsen Makhmalbaf.

Humanism—A Major Characteristic of Iranian Cinema?

That Iranian cinema is characterized by humanism is a truism, and an irony that increases its fascination for the audience because it contradicts the media representation of the country.

While Hamid Naficy has spoken of “the small and humanist topics,”32Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, vol. 4, 175. Saeed Talajooy notes the tendency of critics to “extol the poetic qualities and the ‘humanitarian’ treatment of subject;”33Saeed Talajooy, “Directors: Jafar Panahi,” in Directory of World Cinema: Iran, ed. Parviz Jahed (Bristol: Intellect, 2012), 37. Rose Issa has written a length, that in “Iranian low-budget auteur films” there is a “new, humanistic aesthetic language, determined by the film-makers’ individual and national identity, rather than the forces of globalism,” making it part of the appeal of Iranian cinema, and creating “a strong creative dialogue not only on homeground but with audiences around the world.”34Rose Issa, “Real Fictions.” Dossier: Rose Issa. Haus der Kunst, 8 Mar. 2004. http://archiv.hkw.de/en/dossiers/iran_dossierroseissa/kapitel2.html. Accessed 10 Jan. 2014. Parviz Jahed has noted that humanism (along with poetic qualities) was one of the success factors both internally and externally for “Children Cinema.” For film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum, Iranian cinema is “among the most ethical and humanist.”35Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa and Jonathan Rosenbaum, Abbas Kiarostami (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2003), 2.

Other Factors: Banned in Iran and The Representation of Women

“Banned” in relation to a film is every publicist’s delight for increasing desirability.36Shelly Kraicer in his article “The Use and Abuse of Chinese Cinema” (degenerate films, 9 Dec 2010, www.dgeneratefilms.com/post/shelly-on-film-the-use-and-abuse-of-chinese-cinema-part-two) has listed seven not mutually exclusive categories of ways in which Chinese films selected by Western programmers can be classified. One is for banned films. As he writes “There’s still no more seductive media attractant to spray onto Chinese movies than the overused ‘Banned In China!’ tag.” In relation to Iranian cinema, Naficy has noted that the “Islamic Republic’s severe censoring and its periodic banning and imprisonment of the filmmakers…further whetted the curiosity and appetite for these films.”37Naficy, Social History, 4:176.

Many of the major award-winning films on the Western festival circuit between 2000 and 2013 featured strong female leads and focused on women’s issues. Shahla Lahiji commented in a publication from 2002 that “one of the current criteria for evaluating a cinematographic piece of work is the filmmaker’s attitude to women.”38Shahla Lahiji,“Chaste Dolls and Unchaste Dolls: Women in Iranian Cinema since 1979” in The New Iranian Cinema: Politics, Representation and Identity, ed. Richard Tapper (London: Taurus, 2002), 215. Roughly contemporaneously, in 2000, Deborah Young, then a senior Variety reviewer, wrote of Jafar Panahi’s 2000 Venice Golden Lion winner The Circle:

Dramatizing the terrifying discrimination against women in Iranian society, Jafar Panahi’s The Circle both fascinates and horrifies with its bold assertions about what it means to be a woman under a cruel, institutionalized patriarchy. The pic is shot with such skillful simplicity, the hallmark of Iran’s finest cinema with its content pushing at the outer limits of Iran censorship, Circle was formally banned until recently at home. Circle marks the second Iranian film screened at Venice about female oppression.39Deborah Young, review of The Circle, by Jafar Panahi, Variety, Sep 11, 2000. https://variety.com/2000/film/reviews/the-circle-1200464326/ accessed 28 June 2022.

The trigger words here are “women” and “banned.”

More than a decade later, in 2012, when Jay Weissberg reviewed The Paternal House (dir. Kianoush Ayari), a powerful film about honour killing from Venice, the rhetoric had not changed. He wrote tellingly, in his piece for Variety, that “the pic is a standard-issue sudser without enough of a pro-woman message to propel it beyond home territories.”40Jay Weissberg, review of The Paternal House, by Kianoush Ayari, Variety, 9 Sept. 2012. https://variety.com/2012/scene/reviews/the-paternal-house-1117948275/ accessed 28 June 2022.

Figure 19: Movie poster for The Paternal House (2012), Kianoush Ayari.

International Distribution

Commercial distribution of Iranian cinema has been relatively limited over the years, confined mainly to the more accessible of the award winners from the A list festivals, such as Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s Gabbeh. Most of Jafar Panahi’s films have been acquired by French sales agent Celluloid Dreams, but as Panahi pointed out to me many years ago, never as a pre-sale. The French company MK11 distributed Kiarostami’s whole catalogue. To quote Mohammad Attebai, the most significant Iranian international sales agent working since the 1980s:

As for the commercial release of Iranian films in the world, you know there’s not been any considerable release at the level of commercial or even world-known arthouse filmmakers. There was firstly a circle of a few directors like the Makhmalbafs, Abbas Kiarostami, Majid Majidi and even Abolfazl Jalil whose films were sold to distributors worldwide; but we could see that the Makhmalbafs and Jalili and even Majidi were fading from the market and a new generation, Asghar Farhadi, Jafar Panahi, Bahman Ghobadi, and Mohammad Rasoulof were coming to the market, representing more social/political viewpoints.41Mohammad Atebbai, Email to author 24 June 2022.

But Farhadi’s About Elly made an impact and the French production company Memento Films International subsequently purchased the rights for international distribution of his next film, A Separation, in collaboration with Dreamlab. These were in turn acquired for the American market along with other territories by Sony Classics after the Berlinale premiere afforded Farhadi an opportunity for the essential Oscar campaign for the film. Memento was a producer of Farhadi’s next film, The Past. Most of Farhadi’s films have been widely bought, even retrospectively, since his Academy Award wins. French distributors still purchase Iranian films. Saeed Roustayi’s Just 6.5 (released in France as La Loi du Tehran) had a very successful French release in July 2021 after its 2020 purchase by Wild Bunch. Hopefully this may pave the way for the next generation.42Atebbai, Email to author 24 June 2022.

The Iranian Diaspora

The Diaspora has produced a number of films, some of which have achieved significant success in the West. A disproportionately high number are directed by women and feature female protagonists. There is an extraordinary list of first features: Marjane Sartrapi’s Persepolis, Shirin Neshat’s Women without Men, Granaz Moussavi’s My Tehran for Sale and Ana Lily Amirpour’s A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014), the last of these hyped and ostensibly described by the director as “the first Iranian vampire spaghetti western.”43Matthew Watkins, “Best Horror Movies Directed by Women”, movieweb 15 March 2022 https://movieweb.com/horror-movies-directed-by-women/#:~:text=2014’s%20A%20Girl%20Walks%20Home%20at%20Night%2C%20is,in%20reality%2C%20it’s%20so%20much%20more%20than%20that.

Figure 20-21: Left: Movie poster for A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014), Ana Lily Amirpour. Right: Movie poster for My Tehran for Sale (2009), Granaz Moussavi.

Juries, Polls, and Entering the Cannon

Another measure of the international reception of Iranian cinema is the inclusion of (mostly) directors or actors on prestigious juries. Directors, including Abbas Kiarostami and Asghar Farhadi, and actors such as Fatemeh Motemad Arya, have received their share of these honors. A notable moment occurred in 2009 when Jafar Panahi, as Head of the Montreal World Film Festival Jury, convinced his accompanying jurors to wear green scarves at the opening and closing of the festival in support of the Green Movement. The inclusion in 2014 of Leila Hatami as part of the famous Cannes all-female jury chaired by Jane Campion and comprised of only five members was another singular moment.

In the 2012 Sight & Sound poll, Kiarostami’s Close-Up made it to number thirty-seven on the “Directors’ 100 Greatest Films of All Time” list,44Directors’ 100 Greatest Films of All Time BFI, www.bfi.org.uk/sight-andsound/polls/greatest-films-all-time/directors-100-best while the same film, along with two other Kiarostami works and Asghar Farhadi’s A Separation, “made it into the top 100 in BBC Culture’s 2018 poll to find the greatest [ever] foreign-language films.”45Hamid Dabashi, “Why Iran creates some of the world’s best films,” BBC https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20181115-the-great-films-that-define-iran

Figure 22: The moment when Jafar Panahi, as Head of the Montreal World Film Festival Jury, convinced his accompanying jurors to wear green scarves at the opening and closing of the festival in support of the Green Movement (2019).

Figure 23: Movie poster for Close-Up (1990), Abbas Kiarostami.

The Post-Ahmadinejad Period

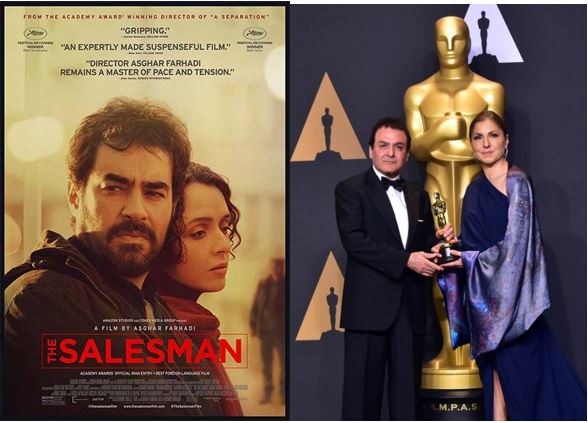

With the beginning of the Rouhani presidency in 2013 the government was at pains to calm its much-publicized conflict with the film industry. However, Mohammad Rasoulof continued to create controversy with A Man of Integrity (2017; winner, Un Certain Regard, Cannes) and There is No Evil (2020; Golden Bear Berlinale). In 2016 Asghar Farhadi won his second Academy Award for The Salesman following recognition for Best Screenplay and Best Actor at Cannes. Among the newer generation to achieve acclaim internationally are Reza Dormishian, Shahram Mokri and Saeed Roustayi.

Figure 24-25: Left: Movie poster for The Salesman (2016), Asghar Farhadi. Right: Anousheh Ansari and Firouz Naderi received the Oscar award in place of Asghar Farhadi.

Conclusion

Following the Islamic Revolution, Iranian cinema re-built itself from a zero base and under new constraints. This unfamiliar cinema was gradually embraced internationally at festivals till in 2000 it acquired the status of a movement—The New Iranian Cinema. By then it had collected a serious number of major festival awards, and by 2012 its first Academy Award, cementing it firmly as a national cinema of importance. Its appeal has been variously ascribed to its humanism, its simplicity and the small scale of the works (although this has changed with time), but geopolitical topicality has also been a major factor. Its popularity has waxed and waned. While Abbas Kiarostami has reached a high level of international recognition, serious commercial reception, with the possible exception of Farhadi’s films, has yet to be achieved.

Cite this article

Iranian cinema first gained international recognition in the 1960s with groundbreaking works like Forough Farrokhzad’s The House is Black (1962) and Darius Mehrjui’s The Cow (1969). The Islamic Revolution of 1979 disrupted production, but the establishment of the Farabi Cinema Foundation in 1983 revitalized the industry. Post-revolutionary films like Abbas Kiarostami’s Where is the Friend’s House? (1986) and Asghar Farhadi’s A Separation (2011) brought global acclaim, highlighting the resilience and creativity of Iranian filmmakers. This article charts the evolution of Iranian cinema’s international reception, from its early presence at European film festivals to its current status as a significant cultural force, emphasizing how Iranian filmmakers navigate cultural constraints to produce art that resonates worldwide.