The Iranian Occidentalist Gaze: Eroticizing Western Modernity and Patriarchal Reactions in Late Pahlavī Era Cinema

Introduction

Iranian cinema of the late Pahlavī era vividly portrays the encounter between Iranian men and the Western world, often through the figure of Western women who embody modernization and allure.1Parviz Ejlali, Digar-gūnī-i ijtimāʿī va fīlm-hā-yi sīnimāʾī dar Īrān [Social transformation and cinematic films in Iran] (Tehran: Nashr-i Āgah, 2017), 300-301. By the 1970s, increased international travel opportunities and a growing presence of Western tourists in Iran made these encounters familiar motifs in popular films. These narratives generally follow two tropes: an Iranian man navigating life in the West, or a Western woman arriving in Iran. Both tropes sexualize and exoticize Western culture, focusing on Western women as symbols of modern progress and desire.2Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 1: The Artisanal Era, 1897–1941 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 241-244; Parviz Ejlali, Digar-gūnī-i ijtimāʿī va fīlm-hā-yi sīnimāʾī dar Īrān [Social transformation and cinematic films in Iran] (Tehran: Nashr-i Āgah, 2017), 301-305. These films emphasize the West’s allure as well as its perceived dangers by implicitly contrasting Western freedom with Iranian tradition.

This article argues that these cinematic encounters reflect an Occidentalist gaze—a mode of representation in which Iranians construct images of the West that both admire and critique it—that simultaneously eroticizes Western modernity and provokes patriarchal reactions in Iranian society. The Western female characters in these films are portrayed as both objects of desire and sources of moral testing. Through their outcomes—typically a return to Iranian values or a reaffirmation of traditional gender roles—the films highlight what in Iranian culture is to be retained or rejected in the face of Western influence.

To illustrate this argument, we examine a selection of key films from the 1970s, each portraying an Iranian man’s encounter with the West (often symbolized by a Western woman or a Westernized Iranian woman). Mr. Naïve (Āqā-yi Hālū, 1970), directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī, follows a naive villager, Hālū, who moves to Tehran seeking a modern wife but becomes disillusioned by the city’s Westernized sexual culture and returns to his village. An Isfahani in New York (Yak Isfahānī dar Nīyu Yurk, 1972), directed by Māshā’Allāh Nāziriyān, tells of Ahmad (Nusratallāh Vahdat), an Iranian who travels to New York to help his brother recover stolen money; with the help of his brother’s fiancée Susan (Rota Panz), Ahmad retrieves the money and returns to Iran with Susan, highlighting both the allure of Western freedom and the comforts of home.

In another instance, Mehdi in Black and Hot Mini Pants (Mahdī Mishkī va Shalvārak-i Dāgh, 1972), directed by Nizām Fātimī, a rural cattle farmer Mahdī (Nāsir Malik-Mutī‛ī) falls in love with Christine (Christian Patterson), a Dutch agricultural expert. Christine ultimately converts to Islam and marries Mahdī, blending Western modernity with Iranian tradition. Rizā Safā’ī’s Iranian Woman Is to Die For (Qurbūn-i Zan-i Īrūnī, 1973) follows Ahmad Bā-Muruvat (Mansūr Sipihrniyā), who, during a trip to London, falls for a Western woman (Maria, played by Carol Weiler). After Maria betrays him, Ahmad realizes his mistake and returns to his wife and family in Iran. In Khusraw Parvīzī’s Akbar Dīlmāj (1973), telephone operator Akbar (Rizā Arhām Sadr) becomes involved with Catherine Farmer (Shūrangīz Tabātabā’ī), a European tourist visiting Tehran, causing conflict at home; ultimately, Akbar reaffirms his commitment to his Iranian wife, Malīhah (Irene), underscoring the primacy of traditional marital values.

Other films from the period continue this theme. Farīdūn Gulah’s Under the Skin of Night (Zīr-i Pūst-i Shab, 1974) features Qāsim (Murtazā ‛Aghīlī), a drifter who spends a long night walking with a foreign woman in Tehran; their encounter ends without fulfillment or lasting change. Shāpūr Qarīb’s Eastern Man and Western Woman (Mard-i Sharqī va Zan-i Farangī, 1975) follows ‛Alī (also played by Murtazā ‛Aghīlī), a photographer who neglects his fiancée after meeting Barbara (Justine), a Western cabaret dancer; his infatuation leads to family turmoil and tragedy. Finally, ‛Abbās Jalīlvand’s Charlotte Comes to the Market (Shārlūt bih Bāzārchah Mī-āyad, 1977) portrays Akram (Nūrī Kasrā’ī), an Iranian woman nicknamed Charlotte after years abroad, who returns to her southern hometown with Western companions; their presence sparks cultural clashes that culminate in her brother Akbar’s death and societal chaos.

In each of these films, however, the narrative resolution tends to reaffirm traditional Iranian values. The protagonist’s dalliance with the West is usually portrayed as a temporary temptation: Hālū renounces his search for a Westernized wife and returns to village life in Mr. Naïve, Ahmad goes back to his Iranian family in Iranian Woman Is to Die For, Akbar chooses his wife in Akbar Dīlmāj, and ‛Alī faces tragic consequences in Eastern Man and Western Woman. Even Mahdī’s marriage to a Western woman endures only after she assimilates by adopting Iranian norms. These outcomes suggest that, while Western women are eroticized on screen, they ultimately reinforce Iran’s patriarchal social order by guiding men back to the security of their own culture.

By focusing on a set of influential films from the 1970s, this article seeks to reveal how these works construct Occidentalism: how they engage with Western modernity by eroticizing Western women through a sexualized gaze, how they embody the simultaneous attraction to and fear of the West, how they negotiate the tensions between tradition and modernity, and how they envision cultural change while ultimately reaffirming patriarchal boundaries.

Since this study focuses on a small number of films to conduct a nuanced examination of their representations of Occidentalism and individual characteristics and distinctions, it does not aim to create a broad categorization of Iranian films depicting encounters with the West. Instead, it analyzes the Occidentalism present in these films to assemble an image highlighting both their differing perspectives and commonalities. This analysis contributes to a broader understanding of how Occidentalism was represented in Iranian cinema during a period when public encounters with the West were becoming increasingly visible in everyday life.

Literature Review

Over the past few decades, the term Occidentalism has gained prominence in both academic and popular discourse. The term Occidentalism refers to the ways non-Western societies perceive and represent the West.3James G. Carrier, “Introduction,” in Occidentalism: Images of the West, ed. James G. Carrier (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 3. It is often framed as a counterpoint to Edward Said’s Orientalism, which critiques Western portrayals of the East. Occidentalism, in contrast, examines how the West is perceived by non-Western observers, alongside the frameworks, stereotypes, and ideologies they employ to depict, critique, and valorize it.4James G. Carrier, “Introduction,” in Occidentalism: Images of the West, ed. James G. Carrier (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 4. Occidentalist discourse frequently internalizes Western narratives of progress and power, casting the West as a model civilization and the non-West as backward or in need of reform. In Iranian intellectual thought, Western societies were often seen as technologically advanced yet morally compromised. Iranian reformers and writers typically admired Western advances in science and culture while warning against Western vices (such as materialism, colonialism, or moral decay).5Zhand Shakibi, Pahlavi Iran and the Politics of Occidentalism (London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 2020), 16. This framework shaped modern Iranian self-awareness, as thinkers debated which Western elements to adopt and which traditional values to preserve.

In his pivotal examination of Iranian Occidentalism, Refashioning Iran: Orientalism, Occidentalism and Historiography, Mohammad Tavakoli-Targhi explores such an Occidenatilism regarding the Western Other in the perspectives of early Iranian European travelers and modernists. He posits that these individuals “gazed and returned the gaze and, in the process of ‘cultural looking,’ they, like their European counterparts, exoticized and eroticized the Other.”6Mohammad Tavakoli-Targhi, Refashioning Iran: Orientalism, Occidentalism and Historiography (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001), 36. Through his analysis of historical accounts by travelers, merchants, and political figures who visited the West or engaged with it indirectly through its narratives, Tavakoli-Targhi introduces the concept of the “voy(ag)eur” to characterize these figures’ preoccupation with the West. A notable and recurring trait among these voyagers is their erotic gaze directed at the European Woman (zan-i farangī), who, as Tavakoli-Targhi notes, became “the locus of gaze and erotic fantasy.”7Mohammad Tavakoli-Targhi, Refashioning Iran: Orientalism, Occidentalism and Historiography (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001), 54. He writes:

The travelers’ recounting of their self-experience provided the material for the formation of competing discourses on women of Europe. With the political hegemony of Europe, a woman’s body served as an important marker of identity and difference and as a terrain of cultural and political contestations. The eroticized depiction of European women by male travelers engendered a desire for that “heaven on earth” and its uninhibited and fairy-like residents who displayed their beauty and mingled with men. The attraction of Europe and European women figured into political contestations and conditioned the formation of new political discourses and identities.8Mohammad Tavakoli-Targhi, Refashioning Iran: Orientalism, Occidentalism and Historiography (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001), 53.

The image of the modern European woman thus became a symbol of Western allure and advancement in Iranian Occidentalism, highlighting what was perceived as lacking in Iranian society, which was in turn symbolized through the “traditional Iranian woman.”9Camron Michael Amin, The Making of the Modern Iranian Woman: Gender, State Policy, and Popular Culture, 1865–1946 (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2002), 48. Conversely, this depiction in Iranian Occidentalism, also underscored aspects in which the homeland was perceived to surpass the West, such as adherence to traditional gender roles characterized by “modesty” and “decency” in women and “honor” in men. These values were perceived to have been lost in the West, where men no longer upheld their roles as guardians.10Mohammad Tavakoli-Targhi, Refashioning Iran: Orientalism, Occidentalism and Historiography (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001), 65-70. Therefore, the sexualized gaze of Iranian modernists and travelers, often marking their initial encounter with the West, played a significant role in delineating what needed to be changed, retained, or rejected in various discourses of Iranian modernity and their visions for the nation’s modernization.11Afsaneh Najmabadi, “Hazards of Modernity and Morality: Women, State and Ideology in Contemporary Iran,” in Women, Islam and the State, ed. Deniz Kandiyoti (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1991), 54-83.

By the mid-twentieth century, this form of Occidentalism and the encounter with the West had spread among a broader range of metropolitan groups. Following the Allied invasion of Iran during the Second World War and the subsequent proliferation of modern mass media such as newspapers, radio, cinema, and television, encounters with the West expanded beyond the elite and upper classes. This shift was especially pronounced after the 1950s, with the rise of consumerism and its associated visual culture in urban centers, which facilitated broader exposure to Western culture. Subsequently, the middle and lower urban classes’ interaction with the West was often framed through an erotic and sexualized lens. A similar gaze was directed toward the modern Iranian woman, who, by adopting European fashion, makeup, and public presence, was derogatorily labeled as a “Western doll” (ʿarūsak-i farangī).12Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 2: The Industrializing Years, 1941–1978 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), 50. Such erotic gaze and subsequent depictions simultaneously provoked attraction and desire, as well as repulsion and fear toward Western women. As symbols of the West, these figures embodied the dual response that exemplified Iranian ambivalence toward modernization and Western influence.13Parviz Ejlali, Digar-gūnī-i ijtimāʿī va fīlm-hā-yi sīnimāʾī dar Īrān [Social transformation and cinematic films in Iran] (Tehran: Nashr-i Āgah, 2017), 354-357. Consequently, such encounters retained a central role in discourses surrounding Iranian modernity.

One of the most illustrative cultural mediums that captured Iranians’ encounter with the West and the ensuing sexualized and fetishistic gaze was Iranian cinema. Film scholars such as Hamid Naficy, Parviz Ejlali, and Golbarg Rekabtalaei have noted this trend in late Pahlavī cinema, and have linked these cultural motifs to specific film genres.14Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 2: The Industrializing Years, 1941–1978 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), chap. 4; Parviz Ejlali, Digar-gūnī-i ijtimāʿī va fīlm-hā-yi sīnimāʾī dar Īrān [Social transformation and cinematic films in Iran] (Tehran: Nashr-i Āgah, 2017), 300-307; Golbarg Rekabtalaei, Iranian Cosmopolitanism: A Cinematic History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 223-228. This type of films form a prominent genre in 1960s–70s films and have often been characterized as “Western bride” genre, named after a seminal film directed by Nusratallāh Vahdat in 1964, in which an Iranian man’s marriage to a Western woman carries a moral lesson.15Golbarg Rekabtalaei, Iranian Cosmopolitanism: A Cinematic History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 223. They argue that these films dramatize the clash between tradition and modernity, and emphasize how such films carry moral lessons—often ending with the Iranian protagonist rejecting the Western influence or assimilating it on Iranian terms (for example, by reaffirming the traditional family or homeland).

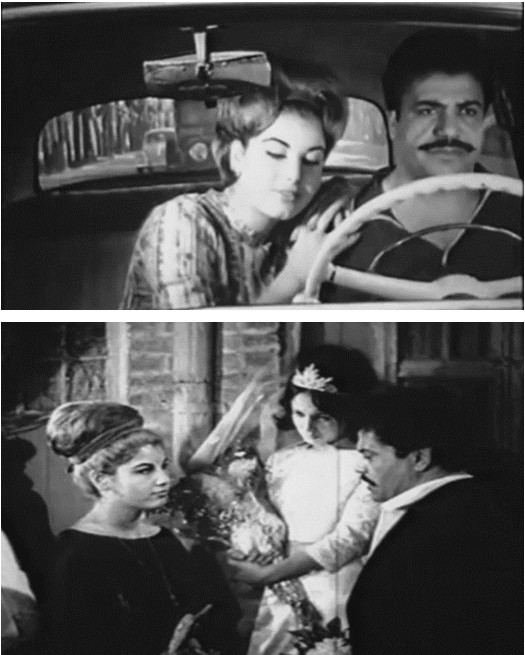

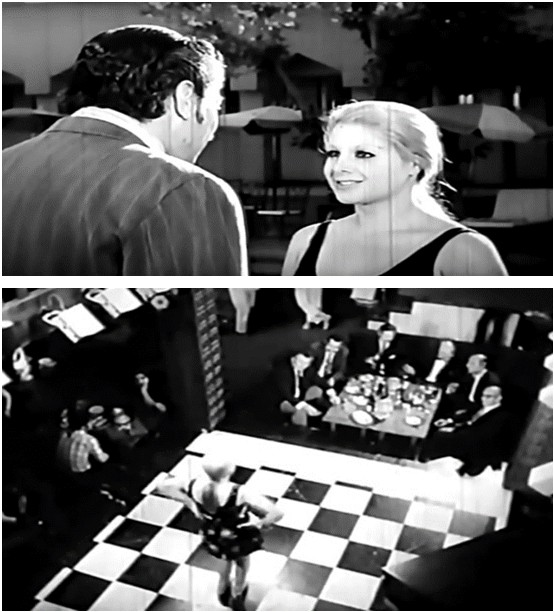

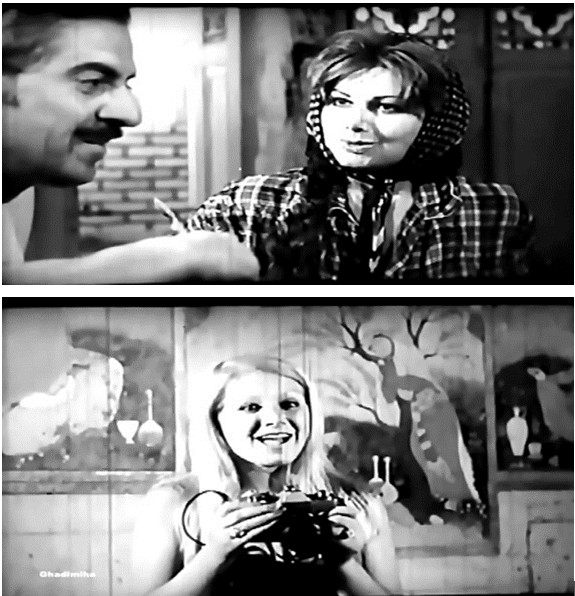

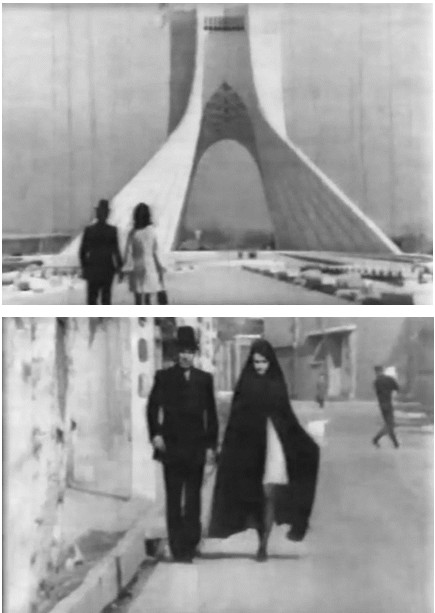

Figures 1 & 2: Most analyses broadly group themes across films, focusing mainly on “Western bride” narratives about Iranian men marrying Western women, as seen in ‛Arūs Farangī (Western bride), directed by Nusratallāh Vahdat. 1964.

However, most existing analyses take a broad view of the genre, aggregating motifs across many films. They have not fully explored how the Occidentalist gaze operates differently in each story, nor considered encounters with the West outside of the marriage framework. This research builds on their work by examining selected films individually, thereby revealing how each film’s portrayal of the West varies. By analyzing a focused set of films, we uncover both the common anxieties about modernization and the unique perspectives each story offers on East–West encounters.

Occidentalism as Erotic Spectacle

Western modernity is repeatedly personified as a sexualized feminine presence in these films, portrayed through the image of Western women who become objects of an intense male gaze. Across the examples, the West is symbolically equated with eroticized female bodies, suggesting that the allure of Western progress and culture is inseparable from the sight of liberated, unveiled women. This pattern – framing the West as an enticing yet morally suspect female figure – provides a unifying argument for the section. The filmmakers present Western women in a way echoing historical impressions of Europe as a “paradise on Earth” populated by “angels” (houris, sg. hūrī), for Iranian male onlookers, even as this paradise is tinged with fear and admonition.16Afsaneh Najmabadi, Women with Mustaches and Men without Beards: Gender and Sexual Anxieties of Iranian Modernity (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2005), 46-47. In what follows, close readings of key scenes will illustrate how this trope is constructed formally (through camerawork, editing, and performance) and narratively, before connecting these cinematic depictions to broader historical and theoretical contexts.

Iranian Woman Is to Die For provides a clear starting point. In this comedy, the protagonist Ahmad’s first experience of London is filtered entirely through a voyeuristic fascination with Western women. On the drive from the airport, he spots a group of young women and is so mesmerized that he asks the driver to stop so he can watch them. Upon arriving in the city, Ahmad remains fixated on one beautiful woman, Maria, whose modern, unveiled appearance immediately captivates him. As he rides through London’s bustling streets – passing modern buildings and busy traffic – the camera aligns with Ahmad’s perspective, showing that his gaze is locked onto Maria rather than the skyline. The effect is to fetishize Maria as the embodiment of the West’s allure. To this provincial visitor, the true marvel of modern London is not its technology or infrastructure, but the sight of liberated Western women moving freely in public, appearing almost like the houris of a worldly paradise. Ahmad’s enchanted reaction implies that, for him, Europe itself is this feminine paradise – an earthly Eden defined by the unveiled beauty of its women.

Figures 3 & 4: Ahmad’s gaze blends desire for Maria with the pulse of the modern western city. Stills from Iranian Woman Is to Die For (Qurbūn-i Zan-i Īrūnī), directed by Rizā Safā’ī, 1973.

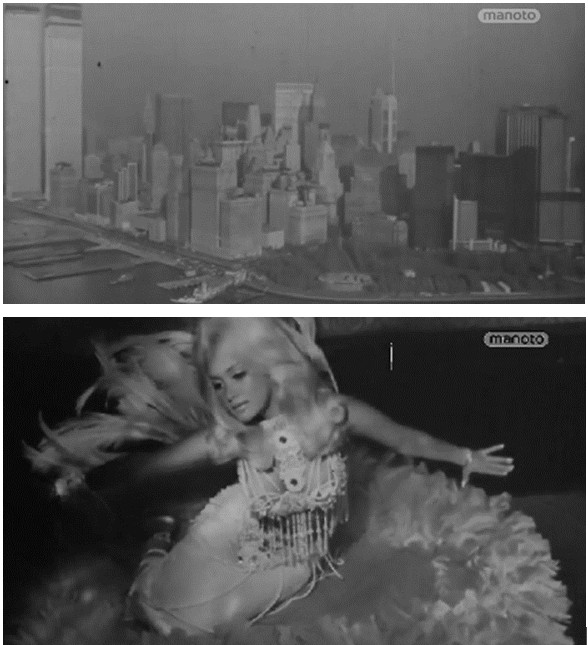

This theme of equating Western modernity with sexualized femininity recurs in An Isfahani in New York. The film’s opening montage introduces the United States through iconic images of New York City’s modernity – towering skyscrapers, neon-lit streets, bustling crowds. Yet this celebration of the Western city immediately gives way to a dance hall scene, where the camera pointedly lingers on a semi-clad female performer on stage. By fixating on a blonde showgirl amid the master shots of Manhattan, the film symbolically links the West’s urban and technological advancement to the image of the Western woman’s revealed body. When the Iranian protagonist (also named Ahmad) arrives in New York, his encounters with the city remain dominated by a voyeuristic gaze at women.

Figures 5 & 6: The film unveils New York’s modernity, linking Western urban grandeur with Western women’s allure, seen through Ahmad’s fascinated gaze. Stills from An Isfahani in New York (Yak Isfahānī dar Nīyu Yurk), directed by Māshā’Allāh Nāziriyān. 1972.

He is fascinated and unsettled by the fashions and freedom of the women he sees – their short skirts, public intimacy with men, and casual socializing in mixed company. These sights echo the unfamiliar sexual dynamics that early Iranian travelers had described upon visiting Europe, where women’s public visibility and interactions with men felt astonishing and exotic. In An Isfahani in New York, the West comes into focus primarily as a spectacle of female sexuality that both entrances Ahmad and leaves him culturally disoriented.

An Isfahani in the Land of Hitler (Yak Isfahānī dar Sarzamīn-i Hītlir) amplifies this voyeuristic dynamic even further in its depiction of an Iranian man’s adventures in Germany. From the outset, the film presents Western space as explicitly sexualized. The opening title sequence pairs images of Europe’s attractions with shots of attractive blonde women, conflating Western landmarks with feminine allure. As the protagonist Mirza Bāqir travels by train toward Germany, his initiation into the “land of Hitler” begins with an intense, silent fixation on a Western woman in his compartment – an encounter conveyed entirely through his captivated gaze at her. Upon his arrival, Mirza Bāqir’s experiences revolve around overtly erotic settings like cabarets and nightclubs, which the film showcases as emblematic Western spaces. On stage, female performers execute striptease acts that become the focal point of the narrative, suggesting that for this Iranian traveler, the essence of Germany lies in its permissive sexual entertainment. Notably, the only Western character with whom Mirza Bāqir directly converses is an eccentric German widow – and she immediately attempts to draw him into a bizarre sadomasochistic role-play, mistaking him for her deceased husband. This comic-subplot underscores the film’s exaggerated portrayal of Western women as sexually aggressive and transgressive. Through such episodes, An Isfahani in the Land of Hitler mirrors and intensifies the same conceit seen in the earlier films: the West is a tantalizing realm of sexual freedom and deviance, observed with a mix of desire and alarm through the eyes of an Eastern voyeur.

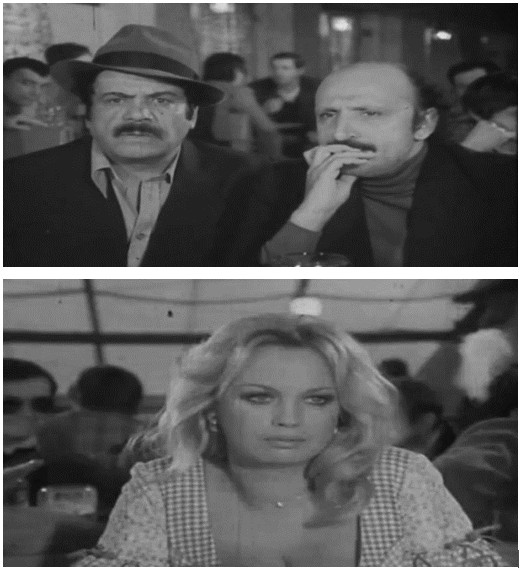

Figures 7 & 8: Mirza Bāqir’s journey reveals Germany’s seductive allure, culminating in a tense encounter with a mysterious German widow. Stills from An Isfahani in the Land of Hitler (Yak Isfahānī dar Sarzamīn-i Hītlir), directed by Nusratallāh Vahdat, 1976.

A similar critique of Westernization as a corrupting, sexualized force appears in Iranian films set on home soil. In Mr. Naïve (1970), the protagonist’s first foray into the big city (Tehran) is accompanied by an overwhelming visual assault of Western-style sexual imagery. The film pointedly equates the Western with commodified sexuality at every turn. Billboards and shop windows display scantily-clad women advertising products; magazine covers at newsstands feature provocative images of European pin-ups; and cinema posters show intimate scenes from foreign films. Modern buildings, factories, and urban bustle form only the backdrop to these seductive images. The wide-eyed country bumpkin, Mr. Naïve, pauses repeatedly to gaze at the posters and advertisements, intoxicating himself on this eroticized visual culture. Enjoying the anonymity of the city crowd, he indulges in looking without restraint, effectively becoming a voyeur of Western decadence in his own country. These shocks and visual stimuli of the Westernized modern city leave their impact on Mr. Naïve’s mind and psyche, and at night, he dreams of a blonde Western woman in the hotel. Tellingly, after this first day in the city, the West even invades his subconscious: that night Mr. Naïve dreams of a blonde, overtly sexual Western woman, who beckons to him as the embodiment of his desires. This dream sequence makes explicit what the urban imagery suggested – that to Mr. Naïve (and, by extension, the film’s viewpoint), “the West” is synonymous with an alluring female sexuality, a temptation that is both exciting and morally suspect.

Figures 9 & 10: Mr. Naïve’s urban journey reveals a city saturated with Western sexualized imagery, which dominates his experience and haunts his dreams. Stills from Mr. Naïve (Āqā-yi Hālū), directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī, 1970.

Under the Skin of Night pushes this idea further by making the male gaze itself the subject of critique through formal techniques. In this film, the Westernized city is once again portrayed as a sexualized landscape saturated with images of women’s bodies, but the cinematic style goes to great lengths to articulate the protagonist Qāsim’s erotic gaze. In one striking sequence, Qāsim stops in front of a newspaper kiosk displaying European magazines. The camera alternates between shots of Qāsim and point-of-view shots of the magazine covers, scanning across rows of half-naked women in glossy photos. The lens finally lingers on one particularly suggestive cover before cutting to a close-up of Qāsim’s face – his eyes wide, lips parted in delight. The correspondence of these shots makes clear that we are looking with Qāsim; the display of scantily clad Western women exists purely for his (and the viewer’s) scopophilic pleasure. Qāsim’s body language then cheekily externalizes his arousal: he raises a finger to his mouth and sucks on it, an infantile gesture of longing that the film uses repeatedly to signify his titillation. In a later scene, outside a cinema showing a foreign movie, Qāsim becomes transfixed by a poster depicting nude lovers in an embrace. As he stares, he unconsciously grips a nearby metal traffic sign and begins to shake it back and forth rhythmically – an unmistakable visual metaphor for masturbation. Through such details, Under the Skin of Night lays bare the normally invisible mechanism of the “determining male gaze” in cinema.17Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” in Feminist Film Theory, ed. Sue Thornham (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1999), 62. The Western woman here is not only an object of desire but also a structural device: her image “connotes to-be-looked-at-ness” in the purest sense, organizing the city’s visual space around Qāsim’s voyeuristic pleasure.18Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” in Feminist Film Theory, ed. Sue Thornham (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1999), 63. By overtly encoding the protagonist’s erotic gaze into camera movements and actor gestures, the film both indulges in and critiques the act of viewing Western female sexuality as the ultimate spectacle.

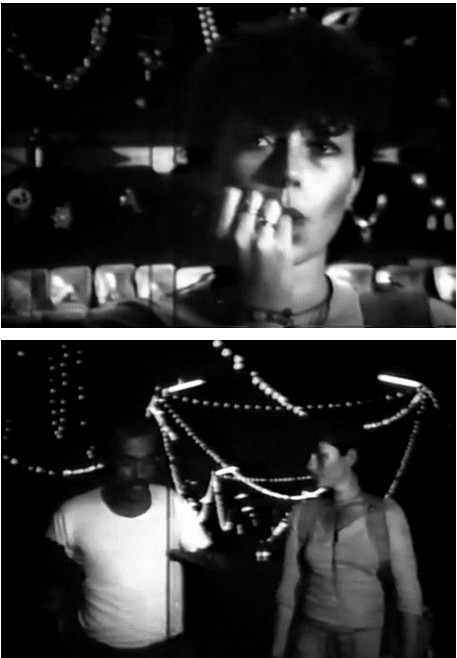

Figures 11 & 12: Through Qāsim’s eyes, the Westernized city becomes a stream of sexual commodities, culminating in fixation on a lone female tourist. Stills from Under the Skin of Night (Zīr-i Pūst-i Shab), directed by Farīdūn Gulah, 1974.

When Western women physically enter Iranian spaces in these films, they are introduced as erotic spectacles in ways that fragment and objectify them from the very first shot. In Akbar Dīlmāj, for example, the European tourist Catherine arrives at a Tehran hotel poolside and is immediately established as a cinematic object of desire. The camera’s first glimpse of her is stylized and symbolic: it pans slowly across the shimmering water of the pool, where the building’s reflection ripples upside-down, until the movement reveals Catherine sunbathing in a bikini. She is splayed out at the pool’s edge, her whole body presented in the frame, while two men – Akbar and his friend Ja‛far – wander into the shot. Significantly, at first only the men’s lower bodies are visible on camera, literally reducing them to anonymous pairs of legs positioned across the pool from Catherine. This compositional choice emphasizes that, from Catherine’s point of view, she is being watched, and from the men’s point of view, only her sexualized form truly fills the screen. Ja‛far cannot help but voice what the visuals already convey: “Look, Akbar… my eyes can’t help but wander,” he says, openly acknowledging their voyeurism.19Akbar Dīlmāj, dir. Khusraw Parvīzī (Iran, 1973), 00:13:16-00:13:20. Noticing their presence, Catherine begins to perform subtle erotic gestures for her spectators: she slowly stretches and dips one leg into the pool, then rises languidly to a standing position, allowing the camera (and the men) to take in her full form. As the camera zooms back to accommodate Akbar and Ja‛far’s reactions, we see them frozen in awe – mouths agape, staring unabashedly. Catherine then approaches to inspect Akbar, walking in a circle around him playfully. Akbar quips, “Perhaps I should circle around you instead, so you don’t get dizzy,” a flirtatious remark laden with sexual innuendo. Throughout this exchange, Ja‛far remains silent, his eyes hidden behind dark sunglasses as he openly ogles Catherine’s body from head to toe. Once Catherine decides to hire Akbar as her local guide, the film cuts to the front of the hotel where Akbar waits with a horse carriage. As Catherine emerges, Akbar and Ja‛far engage in an exaggerated pantomime of male appreciation – winking at each other, adjusting their postures, and practically salivating as she walks by. In these moments, Akbar Dīlmāj leaves no doubt that Catherine is not characterized by any personal depth or agency; rather, she operates as a living fetish of Western femininity. The director’s use of slow pans, zooms, and fragmented framing (showing only parts of bodies) emphasizes the act of looking at her, while the overtly sexual dialogue and gestures from the men confirm that Catherine’s role is to embody a Western fantasy figure. She exists on screen less as a character than as a “cinematic surface” for male projection – the fetishized embodiment of Western modernity in female form.

Figures 13 & 14: Akbar’s life changes when he meets Catherine, a Western tourist depicted as a sexualized commodity, sparking desire and fascination around her. Stills from Akbar Dīlmāj, directed by Khusraw Parvīzī, 1973.

Charlotte Comes to the Market offers a variation on this scenario by placing a Western (or Westernized) woman into a traditional Iranian small-town setting – only to have her met with the same collective male gaze of astonishment and lust. In the film, a group of visitors arrives in a conservative neighborhood: among them are European guests and an Iranian woman named Akram who has returned from Europe having transformed herself into “Charlotte.” Initially, the community greets these visitors with formal hospitality and religious rituals, a gesture of cultural respect. However, as soon as the initial courtesies pass, the film pointedly shifts focus to the visual impact of the outsiders’ presence – especially the unveiled, fashionably dressed women (both the European woman and the Iran-born Charlotte, who is now indistinguishable from a Westerner in style). The camera pointedly shows close-ups of the women’s feet and legs stepping into the scene, highlighting modern high heels and revealing clothes. These shots are rapidly intercut with reaction shots of local men’s faces, wide-eyed and gawking. The implication is clear: to the Iranian male onlookers, the arrival of Western women (and Westernized women) is first and foremost a sexual event. This dynamic persists throughout the film. In one sequence, Charlotte (Akram) attempts to sunbathe in the privacy of a walled courtyard, only for a throng of neighborhood men to secretly climb onto rooftops and balconies to leer at her in her swimsuit – a tableau that mirrors Catherine’s poolside introduction in Akbar Dīlmāj. By saturating these moments with the perspective of peeping men, Charlotte Comes to the Market pointedly critiques the cultural clash in terms of sexual morality and temptation. The Western influence in the village is boiled down to an erotic disturbance: Charlotte’s modern, skimpy attire and behavior scandalize the local elders, even as they enthrall the younger men. This Occidentalist gaze reduces both the foreign woman and the Westernized Iranian woman to the same level of exotic spectacle, implying that in the eyes of tradition-bound Iranian men, the West is essentially a woman who is glamorous, scantily-clad, and dangerously free. The film thus uses overt sexualization to symbolize the West’s disruptive intrusion into the Iranian heartland, echoing the other films’ portrayal of the West as nothing more (or less) than an enticing female body.

Figures 15 & 16: The film exposes how Western women, including the Westernized Akram, become sexualized objects under Iranian male gazes, highlighting cultural clashes. Stills from Charlotte Comes to the Market (Shārlūt bih Bāzārchah Mī-āyad), directed by ‛Abbās Jalīlvand, 1977.

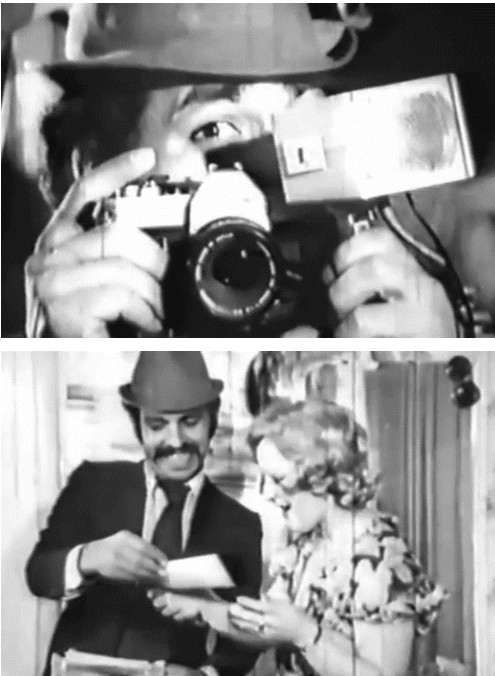

The motif of the Western woman as a seductive disruptor of Iranian life is further apparent in films like The Eastern Man and the Western Woman (Mard-i sharqī, zan-i farangī, 1976) and Mehdi in Black and Hot Mini Pants. In The Eastern Man and the Western Woman, a European woman named Barbara abruptly enters the life of an Iranian man (‛Alī) and is immediately framed as a provocative threat to his moral and social order. The opening scene pointedly has ‛Alī acting as a photographer, taking pictures of Barbara as she poses in scanty clothing. From the first frames, she is presented through the photographer’s lens – literally defined by her sexualized image. Barbara’s flirtatious posing and ‛Alī’s intent focus on capturing her suggest that Westernization, as personified by Barbara, is something that appeals to the eyes yet endangers the equilibrium of ‛Alī’s traditional world. Likewise, in Mehdi in Black and Hot Mini-Pants, the supposed benefits of Western expertise are undermined by the way the Western female expert is depicted. In the story, a young European woman arrives in a rural Iranian community to help the titular character, Mahdī, modernize his cattle farming. Yet the film pointedly reduces her role to that of a sexual object from the moment she appears. Mahdī (and the camera) cannot look past the fact that this woman wears “hot pants” – short shorts – as well as other revealing Western fashions. The point-of-view shots repeatedly cut to her bare legs and mini-skirt, conveying Mahdī’s distracted perspective whenever she is explaining her professional plans. The comedy in these scenes arises from Mahdī’s flustered inability to concentrate on anything but her exposed skin. In effect, her managerial authority and technical knowledge are completely eclipsed by her sexualized presence. She represents Western modernity only inasmuch as she represents sexual liberation and immodesty. Both films, in their titles and content, explicitly pit the “Eastern man” against the “Western woman,” using the woman’s sexuality as the shorthand for all that the West offers and all that it threatens. These Western female characters have agency on paper (Barbara as a bold newcomer, Mahdī’s advisor as an educated expert), but the movies position them chiefly as agents of temptation – exotic interlopers whose feminine wiles throw the orderly, patriarchal norms of Iranian men into comic disarray.

Figures 17 & 18: Barbara’s seductive presence disrupts ‛Alī’s world, symbolizing Westernization’s challenge to Iranian tradition and order. Stills from The Eastern Man and the Western Woman (Mard-i sharqī, zan-i farangī), directed by Shāpūr Qarīb, 1976.

Figures 19 & 20: The Western woman’s mix of competence and sexual allure highlights the clash between modernity and objectification in Mahdī’s world. Stills from Mehdi in Black and Hot Mini Pants (Mahdī Mishkī va Shalvārak-i Dāgh), directed by Nizām Fātimī, 1972.

Taken together, these examples demonstrate a consistent strategy in Iranian cinema of portraying the West via an eroticized female image, inviting the audience to both partake in and critique the male gaze directed at Western women. This cinematic trope is deeply rooted in historical Iranian perceptions of Europe. As historian Mohamad Tavakoli-Targhi observes, many 18th- and 19th-century Persian travelers were astonished by the public visibility of European women. The “appearance of unveiled women in public parks, playhouses, operas, dances, and masquerades” – scenes entirely unfamiliar in their home culture – left these travelers captivated.20Mohammad Tavakoli-Targhi, Refashioning Iran: Orientalism, Occidentalism and Historiography (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001), 55. They described Europe in rapturous terms as a “paradise on Earth,” likening it to the Islamic vision of heaven precisely because of its beautiful, freely mingling women. In their accounts, “desires for Europe were displaced desires for European women,” a telling formulation that highlights how female beauty became the very proxy for Europe’s appeal.21Tavakoli-Targhi references numerous accounts detailing the sexualized gaze of Iranian modernist travelers, highlighting the fascination and intrigue directed towards European women. See Mohammad Tavakoli-Targhi, Refashioning Iran: Orientalism, Occidentalism and Historiography (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001), chap. 4, 62. The travelogues of that era are filled with eroticized depictions of European women – women who appeared “fairy-like” and uninhibited – which in turn engendered a desire for that heaven on earth in the imaginations of Iranian readers back home.22Mohammad Tavakoli-Targhi, Refashioning Iran: Orientalism, Occidentalism and Historiography (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001), 54. Importantly, Tavakoli-Targhi notes that this voyeuristic awe was not universally admiring; it also sparked anxiety. For some observers, the spectacle of European women’s social freedom served as the “precursor of a Europhobic political imagination” – a fearful mindset that sought to protect Iran from Western moral influence.23Mohammad Tavakoli-Targhi, Refashioning Iran: Orientalism, Occidentalism and Historiography (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001), 65. In these reactionary circles, unveiled Western women became symbols of cultural invasion: their sexual allure was thought to portend a “feminization of power” that could weaken Iran’s patriarchal order and invite foreign domination.24Mohammad Tavakoli-Targhi, Refashioning Iran: Orientalism, Occidentalism and Historiography (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001), 65. We can see echoes of these historical attitudes in the films discussed. The filmmakers simultaneously indulge in showing the West as a land of tantalizing feminine charm and warn of its destabilizing effects on Iranian men and society.

The Seductive Dangers of the West

Tavakoli-Targhi’s analysis of the Occidental gaze among Iranian travelers highlights a shift in perception, where the “houris” of one day were later “denigrated as witches” upon closer scrutiny.25Mohammad Tavakoli-Targhi, Refashioning Iran: Orientalism, Occidentalism and Historiography (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001), 58. Both Europhilic and Europhobic accounts of the West caution against traits perceived as detrimental to Iranian values, such as immodesty and a disregard for chastity and honor. Even the most ardent admirers of the West express concerns about uncritical imitation, fearing it could lead to the erosion of distinct gender and religious identities.26Mohammad Tavakoli-Targhi, Refashioning Iran: Orientalism, Occidentalism and Historiography (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001), 72.

One prominent cautionary narrative from early Iranian travelers is Mirza Fattāh Garmrūdī’s account. In 1839, as part of a political delegation to Europe, Mirza Fattāh provided an overtly sexualized description of the West. His narratives, often bordering on the pornographic, highlight the seductive dangers associated with Western attractions.27See Mirza Fattāh Khan Garmrūdī, Safar-nāmah-yi Mīrzā Fattāh Ḵhan Garmrūdī bih Urūpā [Mirza Fattāh Khan Garmrūdī’s travelogue to Europe during Muhammad Shah Qājār’s reign] (Tehran: Bānk-i Bāzargānī-i Īrān, 1969). He emerges as an early proponent of a Europhobic and anti-Western modernist discourse, deeply embedded in sexualized Occidentalism. In this framework, the political threat posed by Europe is linked to the perceived moral and sexual degradation symbolized by European women.28Mohammad Tavakoli-Targhi, Refashioning Iran: Orientalism, Occidentalism and Historiography (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001), 70. This discourse portrays Western women as emblematic of the imperialist traps into which Iranians might fall, adopting European behaviors, assemblies, and customs, thereby turning away from Islamic traditions and values.29Mangol Bayat, Mysticism and Dissent: Socioreligious Thought in Qajar Iran (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1982), 388-389.

Building on these early warnings against the seductive allure of the West, Jalāl Āl-i Ahmad’s concept of “Westoxication” or “Occidentosis” (gharb’zadigī) gained prominence in the 1960s and 1970s. In his seminal work Gharbzadigī, Āl-i Ahmad critiques the pervasive influence of Western culture on non-Western societies, particularly Iran, describing it as a form of cultural and economic dependency that erodes indigenous traditions and autonomy. He likens this phenomenon to a social and individual disease that undermines Iran’s cultural identity and self-reliance.30For information on Āl-i Ahmad’s “Occidentosis,” see Farzin Vahdat, “4. Islamic Revolutionary Thought: The Self as Media ted Subjectivity,” in God and Juggernaut: Iran’s Intellectual Encounter with Modernity (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2002), 131-181; and Ali Mirsepassi, “4. Islam as a modernizing ideology: Al-e Ahmad and Shari’ati,” in Intellectual Discourse and the Politics of Modernization: Negotiating Modernity in Iran (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004). Extending from 19th-century critiques, this discourse uses the Occidental gaze to examine the West’s seductive attractions and their potential to ensnare Iranians, often symbolized by Western or Westernized Iranian women. These figures represent the hollow and perilous allure that threatens to destabilize “authentic” Iranian-Islamic values.31Afsaneh Najmabadi, “Hazards of Modernity and Morality: Women, State and Ideology in Contemporary Iran,” in Women, Islam and the State, ed. Deniz Kandiyoti (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1991), 65-67. As a significant popular discourse, “Westoxication” influenced Iranian cinema from the 1960s onward, and features prominently in several case studies analyzed here.32Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 2: The Industrializing Years, 1941–1978 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), 303-304.

In Iranian Woman Is to Die For, the protagonist Ahmad experiences a profound intoxication driven by the sexualized allure of the West. This intoxication is vividly depicted in a scene where Ahmad, sitting in the bathtub after arriving at his hotel, recalls his encounters with Maria. Presented through his point of view, the memory sequence begins with a shot from inside a car, focusing on Maria’s legs, chest, and face. As the bathroom fills with steam, the scene shifts to Ahmad’s perspective in the bathtub. Through the mist, Maria’s naked form gradually materializes, approaching Ahmad and kissing him. This imagined manifestation of Maria as an exotic and erotic Western figure symbolizes the seductive “spell” consuming Ahmad’s psyche.

Maria’s dominance over Ahmad’s mind becomes increasingly evident as her image intrudes into his professional life. During a business meeting, while Ahmad listens to an elderly woman delivering a speech, he envisions Maria, semi-naked, replacing the speaker. His gaze transforms the room, seeing Maria’s naked body occupying every corner, reflecting the extent to which the Western woman has taken over his thoughts. When his friend Hossein confronts him about his obsession, reminding him of his wife and child in Iran, Ahmad dismisses the reminder, ridiculing his wife’s appearance: “What wife? Every time I saw her, she had stuck skewers and tripods in her hair. She always smeared her face with paste. Look at this woman… she’s like a ripe fruit ready to slide down your throat.”33Iranian Woman Is to Die For, dir. Rizā Safā’ī (Iran, 1973), 01:06:46-01:06:55. Ahmad’s infatuation with Maria leads him to abandon his family, values, and the virtues for which he was once respected.

The film then portrays the inevitable disillusionment that follows Ahmad’s state of “Westoxication.” Although he begins a relationship with Maria, she soon betrays him. This serves as an allegory for Iranian skepticism toward the West rooted in historical experiences of betrayal such as Russian and British imperialism and the 1953 U.S.-orchestrated coup.34Ali Mirsepassi, Intellectual Discourse and the Politics of Modernization: Negotiating Modernity in Iran (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 77-79. Disillusioned by the reality behind the Western allure, Ahmad finds himself spiritually adrift—a state identified by Al-e Ahmad as characteristic of the Westoxicated individual.35Zhand Shakibi, Pahlavi Iran and the Politics of Occidentalism (London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 2020), 158-159. Stripped of his integrity, family, and identity, Ahmad succumbs to despair and ultimately attempts to take his own life.

In Akbar Dīlmāj, a similar narrative of intoxication unfolds, showcasing the protagonist’s descent into obsession with a Western woman and the ensuing personal and cultural consequences. After his initial encounter with the Western woman, Akbar returns home to his wife, Malīhah, but remains mentally consumed by memories of the day. During dinner, Malīhah’s clumsy and unrefined eating contrasts sharply with Akbar’s distant demeanor, as his mind is preoccupied with flashbacks of his experiences. The first memory shown is his encounter with the Western woman by the pool, where her naked body underscores her sexual allure and Akbar’s growing fixation. Subsequent flashbacks detail their interactions throughout the day, emphasizing the extent to which she occupies his thoughts. Akbar neglects Malīhah, who sits nearby, unnoticed and rendered irrelevant.

This preoccupation culminates in a moment of unconscious delight when Akbar mutters, “You’re so beautiful,” lost in his memories.36Akbar Dīlmāj, dir. Khusraw Parvīzī (Iran, 1973), 00:22:01-00:22:05. Malīhah, misinterpreting his words as directed toward her, approaches him romantically. However, Akbar coldly rejects her, signaling the emotional and relational distance created by the Western woman’s intrusion into his life. This marks the onset of his estrangement from his wife and the erosion of his familial bonds.

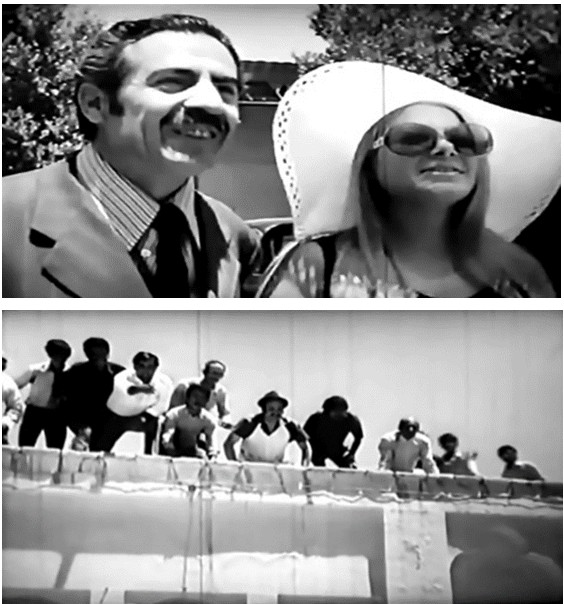

Figures 21 & 22: Akbar’s growing obsession with the Western woman consumes his thoughts, alienating him emotionally from his wife Malīhah. Stills from Akbar Dīlmāj, directed by Khusraw Parvīzī, 1973.

Catherine, the Western woman, further manipulates Akbar, employing calculated seduction to achieve her goal. She invites him to her hotel room, where she appears semi-naked, wrapped in a towel that barely conceals her body. Her motive—to secure a permanent Iranian visa through marriage—reflects a recurring Iranian perception of Western opportunism, wherein personal relationships are exploited for self-serving goals. Catherine’s actions parallel historical anxieties, portraying the West as outwardly seductive but ultimately exploitative.

Catherine ultimately succeeds, becoming Akbar’s second wife. This union symbolizes the catastrophic consequences of succumbing to Western allure. Her “unchaste” behavior disrupts the moral and cultural values central to Akbar’s identity, tarnishing his honor within the local community. Her presence destabilizes the domestic sphere, bringing Akbar’s household to the brink of collapse.

Figures 23 & 24: Catherine’s arrival as Akbar’s second wife shatters his honor, disrupting tradition and destabilizing his family life. Stills from Akbar Dīlmāj, directed by Khusraw Parvīzī, 1973.

The film encapsulates the perceived dangers of Western enchantment, portraying it as a force that corrupts familial and societal structures, undermines traditional values, and leaves the protagonist bereft of stability and honor. Through Akbar’s downfall, the narrative reinforces the theme of cultural betrayal and the destructive outcomes of abandoning one’s roots for the illusory promises of the West.

Building on the theme of familial disruption, An Isfahani in New York portrays the West’s perilous attractions as a corrupting force that derails Ahmad’s brother, Hūshang, during his studies abroad. Falling victim to these temptations, Hūshang abandons his academic purpose, prompting Ahmad’s mission to bring him back home. Upon arriving in New York, Ahmad confronts the forces that have derailed his brother. However, the narrative extends beyond Hūshang to include a particularly vivid scene involving Hājī Mutallib, Hūshang and Ahmad’s father, a devout elder in Isfahan who experiences the West only through Ahmad’s letters. Even secondhand accounts of the West intoxicate him, reflecting the pervasive and disruptive nature of its allure.

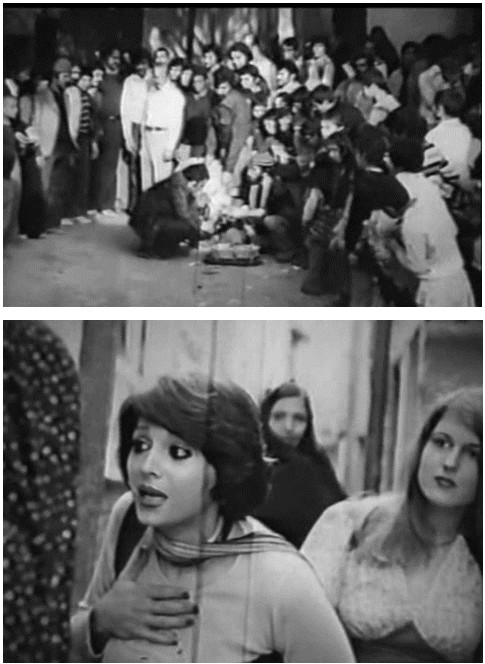

In this scene, Hājī Mutallib reads aloud a letter from Ahmad, recounting that he found Hūshang not studying as expected, but instead in bed with a naked woman who was not his wife. While lying beside his own wife, Hājī Mutallib becomes visibly agitated. When she urges him to let the matter rest and go to sleep, he retorts angrily: “Yes, I should sleep… My good-for-nothing son sleeps with a naked, fair-haired woman in America every night, and I…”37An Isfahani in New York, dir. Māshā’Allāh Nāziriyān (Iran, 1972), 00:52:48-00:52:55. As the scene progresses, Hājī Mutallib’s agitation transforms into jealousy, revealing an inner conflict. As he falls asleep, he dreams of a semi-nude, blonde Western woman provocatively reclining in his wife’s place. Aroused, he moves to embrace her, only to realize it is his wife he is holding. Horrified, he recoils and refuses further intimacy. Delivered with a comic tone, this sequence underscores the disruptive power of Western allure, which not only arouses jealousy and inappropriate desires in a traditionally respectable man but also disturbs his domestic relationships.

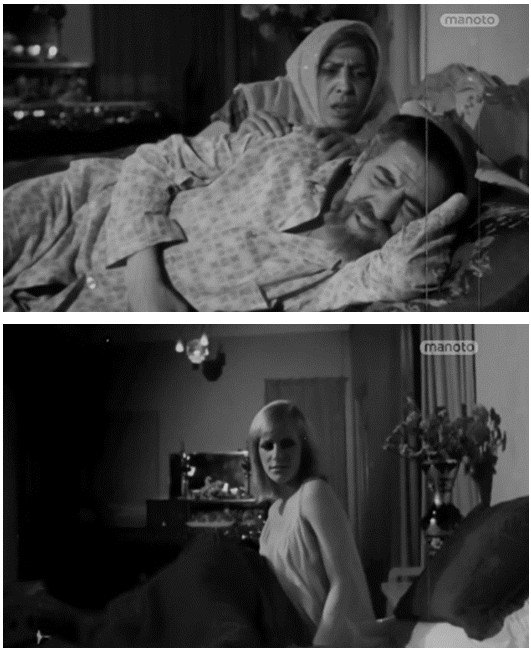

Figures 25 & 26: Jealousy grips Hājī Mutallib, whose dream of a seductive blonde disrupts his honor and strains his marital bond. An Isfahani in New York (Yak Isfahānī dar Nīyu Yurk), directed by Māshā’Allāh Nāziriyān, 1972.

The theme of the Western figure threatening and destabilizing the foundation of the family recurs in Eastern Man and Western Woman, where Barbara is depicted as a deliberate seductress who consciously lures ‛Alī, despite his engagement. She poses provocatively for his camera and lies naked in her bathtub, calling out to him. The film juxtaposes the turmoil in Ahmad’s household—stemming from ‛Alī’s rejection of an arranged marriage to his cousin—with moments of Barbara’s seductive behavior, to emphasize the destructive influence she exerts.

The narrative attempts to rationalize ‛Alī’s betrayal by framing Barbara as a powerful “evil” force determined to disrupt his life and family. In one striking scene, ‛Alī brings Barbara to his family, where her seductive dancing captivates everyone, underscoring the irresistible allure of the West. These depictions critique the Western influence as a destructive force that undermines core Iranian values such as familial cohesion and loyalty.

Similarly, Mr. Naïve portrays the Western consumerist lifestyle associated with urban modernity as inherently at odds with Iranian cultural values. The protagonist, Mr. Naïve, arrives in the city in search of a wife but discovers that this sacred institution cannot thrive in a materialistic society that sexualizes commodities and commodifies sexuality. The urban environment, saturated with consumerism and commodification of sexuality, is depicted as fundamentally incompatible with the moral and cultural values underpinning the traditional Iranian family.

The perceived dangers of Western allure are shown to have a particularly corrosive impact on the family, the most sacred and foundational institution in Iranian society.38Parviz Ejlali, Digar-gūnī-i ijtimāʿī va fīlm-hā-yi sīnimāʾī dar Īrān [Social transformation and cinematic films in Iran] (Tehran: Nashr-i Āgah, 2017), 243-244. These films portray the primary threat of Westoxification as the destabilization of the family structure. Across all the films, the West is depicted as an omnipresent and insidious force that compromises the sanctity of the Iranian family, highlighting the cultural and moral perils associated with Western influence. The threat of Western allure to the family was not merely a cinematic trope, but echoed genuine cultural anxieties in 20th-century Iran. Iranian intellectuals and clerics alike warned that Western-inspired changes – especially those affecting women’s roles – could unravel the traditional family structure. Ever since the early Pahlavī era, advocates of modernization had assured the public that new freedoms for women (education, unveiling, employment) would not erode the sanctity of home and hierarchy; women, it was promised, would still remain devoted wives and mothers even as they gained a public presence.39Janet Afary, Sexual Politics in Modern Iran (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 11. Yet beneath these assurances lay a deep unease. As Afsaneh Najmabadi notes, even a relatively progressive writer like Tālibuf (writing in 1906) praised European advances in women’s education while balking at adopting them in Iran – precisely because he viewed European women’s unveiled socializing (dancing, makeup, low-cut dresses) with “disdain and disapproval,” a “moral anxiety” that Western freedoms would corrupt Iranian women, and through her, Iranian family.40Afsaneh Najmabadi, Women with Mustaches and Men without Beards: Gender and Sexual Anxieties of Iranian Modernity (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2005), 192. By the 1960s–70s this anxiety had intensified: many viewed the Westoxification of Iranian culture as a “plague” eating away at indigenous values, especially, the shallow “feminine consumerism” of the West, sneering that under Western influence Iranians had only given women “the right to parade themselves in public… every day to freshen up and try on a new style.”41Āl-i Ahmad quoted in Shirin S. Deylami, “In the Face of the Machine: Westoxification, Cultural Globalization, and the Making of an Alternative Global Modernity,” Polity 43, no. 2 (2011): 257. Such critiques reveal a fear that Western individualism and sexual openness would destabilize the family – long idealized as the sacred core of Iranian society. In these films, therefore, the West’s omnipresent seduction is portrayed as an insidious force undermining parental authority, marital fidelity, and filial piety. The consistent message is that Westoxification attacks Iran at its moral roots – the family – producing wayward children, immodest women, and disloyal husbands. By dramatically exaggerating broken homes and lost virtues, the films underscore how Westernization was perceived not just as a political or economic threat, but as a cultural poison striking at Iran’s most cherished institution

However, in contrast to the familial themes in previous films, An Isfahani in the Land of Hitler presents a more exaggerated and grotesque portrayal of Western immorality, amplifying its critique of cultural corruption. The film portrays the West in an exaggeratedly sinful and pornographic light, echoing Mirza Fattāh Garmrūdī’s portrayal of the West in his 1842 book, Nocturnal Letter (Shab’nāmah). Mirza Fattāh characterizes Western women as “addicted to pleasure and play” with an “extreme desire for sexual intercourse,” while lacking the fortitude to maintain their “honor.”42Quoted in Mohammad Tavakoli-Targhi, Refashioning Iran: Orientalism, Occidentalism and Historiography (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001), 66. Similarly, Western men are portrayed as sexually impotent and incapable of maintaining authority over their wives.43Janet Afary, Sexual Politics in Modern Iran (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 112. This critique permeates the film, wherein the immoral lifestyles of Western women lead Iranian men into debauchery.

A particularly striking scene epitomizes this exaggerated portrayal: Maria, a German widow, initiates a sadomasochistic encounter with Mirza Bāqir, involving leather whips and mistress-submissive role-play. While the scene denounces Western immorality, it simultaneously hints at repressed desires and enjoyment on the part of the Iranian participant, much like Hājī Mutallib in An Isfahani in New York. As Iranian critic Hassan Hosseini observes, this tension reflects underlying sexual repression.44Hassan Hosseini, “Yak Isfahānī dar Sarzamīn-i Hītlir” [An Isfahani in the land of Hitler], in Rāhnamā-yi fīlm-i sīnimā-yi Īrān: jild-i avval (1309–1361) [A companion to Iranian cinema, part one: 1930–1982], ed. Hassan Hosseini (Tehran: Rūzanah Kār, 2020), 727. In alignment with Garmrūdī’s portrayal of Western women as “daring and exquisite” in fulfilling their partners’ desires,45Quoted in Mohammad Tavakoli-Targhi, Refashioning Iran: Orientalism, Occidentalism and Historiography (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001), 66. Mirza Bāqir, portrayed as a savvy and masculine Iranian man, exploits the situation. However, he rationalizes his actions through religious justification by entering into a temporary marriage (sīghah) with Maria before engaging in the act. Both narratives illuminate the dual nature of the Iranian response to the West, simultaneously critiquing its perceived moral corruption and acknowledging the allure of its forbidden pleasures.

Figures 27 & 28: In a provocative scene, Mirza Bāqir engages in S&M with Maria, a German widow, blending moral critique with hints of repressed Iranian desire. Stills from An Isfahani in the Land of Hitler (Yak Isfahānī dar Sarzamīn-i Hītlir), directed by Nusratallāh Vahdat, 1976.

Iranization of Western Modernity

The portrayal of the West as a threat does not necessarily imply opposition to change or modernization. Instead, the negative depiction, accompanied by a fascinated gaze, can serve as a framework for assessing the extent and nature of change. Zhand Shakibi notes that advocates of change in Iran have always sought to balance the “advantages” and “disadvantages” of Western influence. They advocated adopting aspects of Western modernity deemed beneficial—such as technological, economic, and health advancements—while integrating these with the “virtues” of Iranian-Islamic culture, including honor, family values, chastity, and spirituality.46Zhand Shakibi, Pahlavi Iran and the Politics of Occidentalism (London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 2020), 175-177. Farzin Vahdat identifies these elements as positivist facets of Western modernity,47Farzin Vahdat, God and Juggernaut: Iran’s Intellectual Encounter with Modernity (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2002), chap. 2. while Hamid Naficy describes this integrative approach as a “syncretic” view of modernization.48Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 1: The Artisanal Era, 1897–1941 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 185. This perspective, which emphasized selectively adopting elements of Western modernity thought to contribute to Western “progress” while preserving Iranian-Islamic traditions, has characterized Iranian modernity across various discourses.49Zhand Shakibi, Pahlavi Iran and the Politics of Occidentalism (London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 2020), 172-173. Differences between these discourses often revolved around the degree and specifics of such adaptations and preservations.

The syncretic approach became more pronounced and ideologically entrenched during the calls for a “return to the roots” advocated by figures like Āl-i Ahmad and ‛Alī Sharī‛atī.50Ali Mirsepassi, Intellectual Discourse and the Politics of Modernization: Negotiating Modernity in Iran (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), chap. 4. Despite differing views on what constituted authenticity and how it should be reclaimed, these thinkers converged on the rejection of cultural subjugation and the necessity of prioritizing cultural and religious authenticity.51Ervand Abrahamian, Iran between Two Revolutions (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1982), 466-467. Both called for change and revolution, promoting certain aspects of Western modernity conducive to national progress, while resisting the homogenizing effects of Western imperialism. They warned that unchecked Westernization could lead to moral and social decay as well as the kind of alienation they believed afflicted the Western societies. Instead, they posited that Iran’s Islamic heritage provided a robust moral and spiritual foundation for safeguarding its modernization efforts.

A critical site of this discourse, as previously discussed, has been the feminine body, which played a central role in the “political imagination” of Iranian modernists.52Mohammad Tavakoli-Targhi, Refashioning Iran: Orientalism, Occidentalism and Historiography (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001), 61. The Occidental gaze cast upon Western women inspired a desire to adopt the “best of both worlds” for Iranian women. Exposure to Western consumer culture and changing sexual norms led Iranian modernists to advocate changes in women’s appearance, fashion, demeanor, and speech. Western women’s perceived transformation into houri-like figures was linked to the West’s progress.53Mohammad Tavakoli-Targhi, Refashioning Iran: Orientalism, Occidentalism and Historiography (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001), 62. Yet, this admiration was accompanied by critique, with the Western moral and societal problems projected onto women. Consequently, syncretic modernization required redefining traditional Iranian women—seen as “mired in superstition and ignorance”—into modern figures who could counteract the perceived shortcomings of their predecessors.54Camron Michael Amin, The Making of the Modern Iranian Woman: Gender, State Policy, and Popular Culture, 1865–1946 (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2002), 48. These modern women, constructed within patriarchal frameworks, were envisioned as vital companions to men in the pursuit of Iran’s moral and material renewal. Although they were expected to adopt surface-level changes, they remained bound to traditional roles, maintaining values such as honor, chastity, and familial devotion.55Janet Afary, Sexual Politics in Modern Iran (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), chap. 7. Thus, sexual Occidentalism facilitated a patriarchal vision of modernity. Just as the modern West was symbolized by its women, modern Iran similarly projected its aspirations and anxieties onto the feminine body, with various ideologies—from statist-Pahlavīst to Marxist-leftist and Islamist—adopting this symbolic construct.56For the projection of fears, anxieties and aspirations onto feminine body by various discourses, see Afsaneh Najmabadi, “Hazards of Modernity and Morality: Women, State and Ideology in Contemporary Iran,” in Women, Islam and the State, ed. Deniz Kandiyoti (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1991). See also chapters 2 and 3 in Kamran Talattof, Modernity, Sexuality, and Ideology in Iran: The Life and Legacy of a Popular Female Artist (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2011); and chapter 7 in Janet Afary, Sexual Politics in Modern Iran (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009). This symbolic view of modernization, reflected in the feminine body and debates over what to adopt or reject, is also evident in Akbar Dīlmāj and Iranian Woman is to Die For.

In Akbar Dīlmāj, Akbar represents the ideal modern man within Muhammad Rizā Pahlavī’s bureaucratic system, embodying the urban middle class central to Pahlavī-era modernization. This class, defined by literate, bureaucratic men who adopted Western attire, consumerism, and urban pleasures, considered having a modernized wife essential. By the 1960s and 1970s, this ideal was realized among the upper classes, but most middle- and lower-class women remained unaffected by these changes.57Nafiseh Sharifi, Female Bodies and Sexuality in Iran and the Search for Defiance (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 132.

The film functions as a cautionary tale, urging women to modernize in order to preserve their marriages, ensure family stability, and support national progress. At the beginning of the film, Akbar’s wife, Malīhah, epitomizes the “traditional woman” through unrefined habits—eating from a pot, licking her fingers, and wearing disheveled clothes—that render her undesirable in Akbar’s eyes. In contrast, Catherine embodies modernity: she is attractive and progressive but unwilling to adopt traditional domestic roles, frustrating Akbar with her autonomy and independence.

Malīhah embarks on a transformation, adopting Western-style clothing, makeup, and behavior while retaining traditional values. Guided by Akbar’s sister, she shops for modern outfits, visits a salon, and refines her appearance. Akbar initially fails to recognize her but becomes captivated by her new look and demeanor. Presented with a choice between Catherine’s independence and Malīhah’s modernized obedience, Akbar predictably chooses the latter.

Their reconciliation, with Malīhah now as “attractive” as Catherine but still embodying the values of a “good” and “responsible” wife, takes place in a bedroom with traditional Iranian décor. This setting symbolizes Occidentalist ideal of integrating Western modernity within an Iranian cultural framework. Malīhah’s transformation culminates in her pregnancy, defining her as the “modern-yet-modest” ideal of the modern Iranian woman.58Afsaneh Najmabadi, “Hazards of Modernity and Morality: Women, State and Ideology in Contemporary Iran,” in Women, Islam and the State, ed. Deniz Kandiyoti (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1991), 70.

Her ability to bear a healthy male heir underscores the patriarchal notion that women’s modernization should ultimately serve familial and national agendas, securing Iran’s “progress.”59Afsaneh Najmabadi, “Hazards of Modernity and Morality: Women, State and Ideology in Contemporary Iran,” in Women, Islam and the State, ed. Deniz Kandiyoti (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1991), 49.

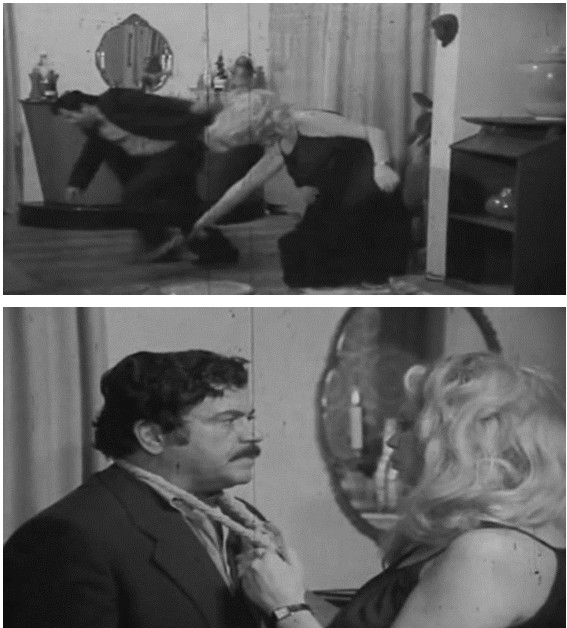

Figures 29 & 30: Stills from Akbar Dīlmāj, directed by Khusraw Parvīzī, 1973. The film portrays women’s modernization as essential for keeping their husbands, strengthening family ties, and advancing the nation—blending tradition with Western influence.

In Iranian Woman Is to Die For, Ahmad, like Akbar in Akbar Dīlmāj, holds a bureaucratic position but remains unmodernized, as reflected in his colleagues’ remarks and his traditional habits, such as eating on the floor despite owning a dining table. His wife, Sakīnah, similarly embodies a traditional lifestyle in her speech and appearance. Ahmad’s journey to the West initiates his transformation through exposure to European women, particularly Maria, whose allure reshapes his aesthetics and expectations. However, the narrative rejects Westoxification, advocating instead a modernized “return to the self,” achievable only through Sakīnah’s transformation.

After rescuing Ahmad from despair and multiple suicide attempts, Sakīnah assumes responsibility for her marital “shortcomings,” confessing her neglect of Ahmad’s physical and emotional needs:

I thought merely taking care of the house and children was fulfilling my duty… While in reality, I had forgotten about you… Perhaps if I had known my duties, you would never have pursued lust, and you wouldn’t be on the edge of this cliff now. Yes, Ahmad, my sin is no less than yours.60Iranian Woman Is to Die For, dir. Rizā Safā’ī (Iran, 1973), 01:30:20-01:30:45.

Following this admission, the couple returns to Tehran, where Sakīnah undergoes a visible transformation in appearance, behavior, and speech. She now combines the aesthetic appeal associated with Western women and the moral integrity of Iranian tradition, rekindling intimacy with Ahmad. The film concludes with a symbolic pilgrimage to Mashhad, Iran’s religious center, via the modern means of air travel. In public spaces, Sakīnah wears a chador, representing the retention of traditional values despite changes in appearance, behavior and speech.

Figures 31 & 32: Ahmad’s encounter with the West triggers change, yet real transformation happens when Sakīnah adapts, merging tradition and modernity to heal their marriage and faith. Stills from Iranian Woman Is to Die For (Qurbūn-i Zan-i Īrūnī), directed by Rizā Safā’ī, 1973.

As such, both Iranian Woman Is to Die For and Akbar Dīlmāj use the Occidental gaze to explore Iranian modernity, emphasizing the pivotal role of the “woman question” in shaping it.61Afsaneh Najmabadi, “Hazards of Modernity and Morality: Women, State and Ideology in Contemporary Iran,” in Women, Islam and the State, ed. Deniz Kandiyoti (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1991), 67. These films envision progress as the selective integration of Western elements into Iranian traditions, embodying a culturally authentic “return to the self.”

It should be noted that there is a stark contrast in how these narratives handle female sexuality – Western women are hyper-sexualized “temptresses,” while Iranian women even in their changed, modern state, are virtually desexualized in anywhere except public spaces. This dichotomy is no accident; it reflects a broader patriarchal discourse from the Pahlavī era that cast Iranian women as symbols of chastity, to be protected and kept morally pure. Men assumed the role of protectors and women the protected, with the home idealized as a sanctified inner realm of virtue.62Minoo Moallem, Between Warrior Brother and Veiled Sister: Islamic Fundamentalism and the Politics of Patriarchy in Iran (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 44-46. Womanhood was equated with motherhood and wifely respectability – in official rhetoric Iran was the “motherland” and women’s highest duty was nurturing the next generations.63Minoo Moallem, Between Warrior Brother and Veiled Sister: Islamic Fundamentalism and the Politics of Patriarchy in Iran (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 72. Within this framework, any open expression of female sexuality was seen as a direct threat to the family and by extension the nation. Tellingly, the Pahlavī state’s own policies reinforced this desexualization. For instance, while Rizā Shah’s regime unveiled respectable women as a sign of modernity, it simultaneously ordered that prostitute (women who embodied transgressive sexuality) remain veiled and out of sight – effectively marking them as outside the respectable social body until they married and became “legitimate.”64Minoo Moallem, Between Warrior Brother and Veiled Sister: Islamic Fundamentalism and the Politics of Patriarchy in Iran (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 73. In popular culture and film, therefore, the ideal modern Iranian woman, although adapting the erotic allure of Western woman at domestic spaces, is virtuous, modest, and subordinated to family roles, and consequently desexualized in society and public spaces. Any illicit erotic indulgence is displaced onto Western female characters, who are demonized for their “sins” even as the films voyeuristically revel in them. This narrative strategy has a sinister undertone: it preserves the illusion of Iranian women’s chastity by erasing their sexual agency, all the while projecting repressed desires onto the figure of the Western femme fatale.

The Iranization of Western modernity is also evident in An Isfahani in New York and Mehdi in Black and Hot Mini Pants, though this time it is achieved through the narrative transformation of Western female characters. In An Isfahani in New York, Susan, Hūshang’s fiancée, becomes disillusioned with the vice and immorality of her homeland, which has led to her fiancé’s moral straying. After Ahmad completes his mission in New York, rescuing his brother and returning to Iran, Susan joins them. Her adoption of the hijab symbolizes her Iranization. This plot development is noteworthy: while Hūshang’s original journey to the West aimed to acquire scientific knowledge for Iran’s benefit, such a mission is depicted as both hazardous and unnecessary. Instead, the narrative implies that it is now the West that must learn from Iran.

This theme aligns with the cultural self-assurance of the “return to the roots” discourse, which exalted an Iranian-Islamic lifestyle and values while rejecting the perceived immorality of the Western “other.” This perspective gained momentum in the late 1960s, reinforced by the state’s adoption of the discourse, which reflected both a strategic political alignment with popular sentiment and an authentic concern about Western cultural influence and moral decline.65Ali Ansari, Modern Iran (London and New York: Routledge, 2007), 222-224; Zhand Shakibi, Pahlavi Iran and the Politics of Occidentalism (London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 2020), 172–174. During this period, as Zhand Shakibi notes, “the shah and members of the Pahlavī elite were… becoming increasingly skeptical of fundamental cultural and moral elements of Western civilization, concerned about the loss of Iranian authenticity, as defined by the state, and confident about Iran’s future.”66Zhand Shakibi, Pahlavi Iran and the Politics of Occidentalism (London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 2020), 187. This confidence manifested in state propaganda, publications, official speeches, and grandiose events such as the inauguration of Shahyād Tower, the coronation ceremony, and the 2,500th-anniversary celebrations of the Achaemenid Empire.67Homa Katouzian, The Political Economy of Modern Iran (London and New York: Macmillan and New York University Press, 1981), 338; Ali Ansari, Modern Iran (London and New York: Routledge, 2007), 235-237.

This vision of national progress was supported by economic, scientific, and technological development, coupled with a belief in moral and spiritual superiority. As part of this vision, the Shah famously stated:

We can very firmly and with absolute certainty say that Iran will not only become an industrial nation but in my assessment in 12 years’ time enter what we say is the era of the Great Civilization… This welfare state doesn’t mean that society will be completely undisciplined. It doesn’t mean that our society will also sink into all the degradation that we can see in some places.68Quoted in Ali Ansari, Modern Iran (London and New York: Routledge, 2007), 219.

This sentiment, led to his aspiration for Iran to be a “model country” for other societies, including the West.69Ali Ansari, Modern Iran (London and New York: Routledge, 2007), 176.

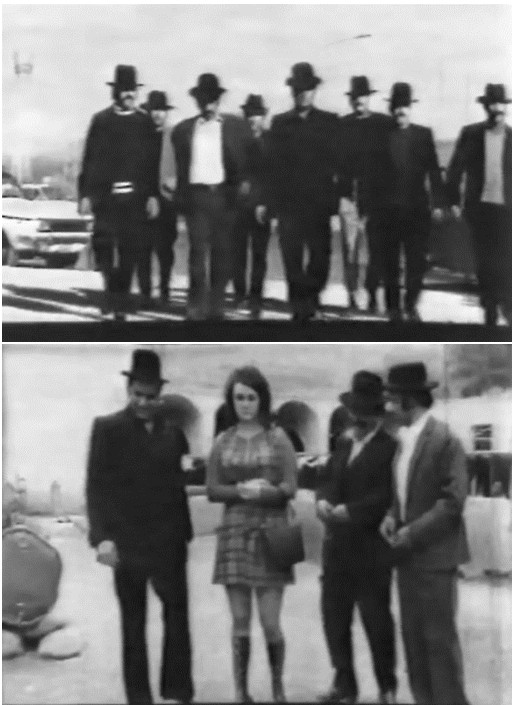

In Mehdi in Black and Hot Mini Pants, this vision is even more pronounced. Mahdī Mishkī interacts confidently with Christine, reducing her professional identity to a sexualized object while introducing her to Iran’s cultural and modern achievements. He guides her through significant landmarks such as the tomb of Hāfiz (Hāfiziyah), Āryāmihr Stadium, Shahyād Tower, and sites related to the 2,500th-anniversary celebrations, linking Iran’s historical legacy with its modernizing aspirations. As Iranian critic Ali Papoli Yazdi notes, “Miss [Christine] Richard has entered a country where the jāhilī [the quintessential patriarchal archetype of the Iranian man] merges with monarchical pride to construct a vision of a new world. The presence of the Shah’s portrait in Mahdī’s office likely serves as a reference to the alignment and collaboration between these cultural and political forces.”70Ali Papoli Yazdi, “Mahdī Mishkī va Shalvārak-i Dāgh” [Mehdi in Black and Hot Mini Pants], in in Rāhnamā-yi fīlm-i sīnimā-yi Īrān: jild-i avval (1309–1361) [A companion to Iranian cinema, part one: 1930–1982], ed. Hassan Hosseini (Tehran: Rūzanah Kār, 2020), 523. Ultimately, Christine’s transformation—her conversion to Islam, adoption of the hijab, and marriage to Mahdī—serves as a metaphor for the Iranization of the Western “other.”

Figures 33 & 34: Christine conversion, hijab, and marriage symbolize the Iranization of the Western other, reflecting jāhilī masculinity fused with monarchical pride. Stills from Mehdi in Black and Hot Mini Pants (Mahdī Mishkī va Shalvārak-i Dāgh), directed by Nizām Fātimī, 1972.

The Occidentalism in these films underscores an assertion of Iranian cultural and moral superiority over the West.

Criticizing Pahlavī Modernization

The Occidental gaze, in some cases, critiques domestic governance and societal issues rather than the West itself. This is evident in Under the Skin of Night, where the director, Farīdūn Gulah, employs such criticism. Gulah does not focus on the adverse effects of the prevalence of Western influences or the Westernization of his homeland. Instead, his critique centers on the exclusion of the protagonist, Qāsim, from participation in this new social order. Qāsim is denied access to the promises and privileges of the Westernized city, positioning him as an outsider. This serves as a critique of the economic and social inequalities within metropolises like Tehran, where consumerist opportunities were restricted to a minority of the urban upper and modern middle classes.71Homa Katouzian, The Political Economy of Modern Iran (London and New York: Macmillan and New York University Press, 1981), 207-209. Meanwhile, the urban lower classes, living in the same environment, were drawn to the city’s glamorous attractions but relegated to mere spectatorship, limited to “window-shopping” rather than actual participation.

The film narrates Qāsim’s disillusionment and eventual rejection of this reality. Initially, he is captivated by the Western attractions embedded in the urban visual culture, believing the city and its streets to be his home, a space where he can share in its opportunities. His encounter with a foreign woman—symbolizing the West—reveals the illusion underlying this belief. At first, Qāsim assumes that securing a “home” is inconsequential since the city itself seems to belong to him. However, as the day transitions into night, the city’s true nature emerges. The dazzling allure of shop displays and Qāsim’s positioning in relation to them exposes a stark reality. The shift reflects a form of “class consciousness,” wherein the city delineates those who live “behind” the display windows—those in possession of its goods—from those confined to remain “in front,” unable to attain what they see.72Janet Ward, Weimar Surfaces (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), 227. Qāsim, firmly situated in the latter category, embodies the frustration of those excluded from the consumerist order. Gulah poignantly illustrates this separation through the couple’s shared frustration at their exclusion from the privileges symbolized by the display window.

The recurring theme of exclusion—seduced by Western influences yet denied access to them—dominates the narrative. Qāsim realizes that the Westernized city excludes individuals like himself, who lack the economic means to participate in its offerings.

In Charlotte Comes to the Market, sexual Occidentalism is also not deployed as a critique of the West itself, but rather as an exploration of the profound tensions and catastrophic outcomes arising from the abrupt and poorly managed imposition of Western values and practices onto Iranian society. The film does not challenge Charlotte’s decision to pursue education in the West, portraying it in a positive light. Instead, it focuses sharply on the cultural dissonance and disastrous consequences that occur when Iran’s traditional boundaries are violated.