The Middle-Class Poor in Iranian Cinema: Shattered Lives, Fading Horizons in At the End of the Night (2024)

She washes chicken pieces with care, sautés herbs for ghormeh sabzi, fries eggplants one by one, slices sangak bread, and neatly packs them all into freezer bundles, performing each task in silence, while simultaneously, and with quiet anxiety, packing her suitcase. This woman, Mahrokh (or Mahi, as she is more commonly called), is not preparing for a trip, but for a final departure—not a vacation, but a separation. The next morning she will leave behind her home, her young son Dara, her husband Behnam, and a life once built on love. And yet, the silence of the kitchen, despite the noise of Dara’s video game in the background, in the opening scene of At the End of the Night speaks to something far deeper than a personal rupture. It is not only the future that is being prepared, but the past that is being carefully sealed and stored—in memory’s freezer.

Before the title credits roll, the camera captures Mahi and Behnam lying side by side on their bed, shoulder to shoulder, motionless, enveloped in wordless sorrow. The mise-en-scène—the bedroom, the shared bed, their parallel bodies—suggests an intimacy that no longer exists. The camera underscores this absence with precision: it moves from medium close-ups of their torsos to close-ups of their faces, only to freeze them into separate, isolated frames. The viewer is left staring at two people who were once in love, now confined to neighboring yet solitary emotional cells.

Figure 1: Opening scene from At the End of the Night (Dar Intihā-yi Shab), directed by Āydā Panāhandah, 2024.

As the series unfolds, this rupture is not pathologized through the language of psychology or reduced to a personal failing. Instead, it is situated within a broader social and economic landscape. This is not simply the story of a collapsing marriage; it is the intimate expression of a larger societal crisis: a slow-moving economic collapse whose shockwaves have dismantled the everyday architecture of life for an educated young middle-class couple, pushing them not only to the edge of the city, but to the margins of meaning, dignity, and belonging.

***

For over a century, Iran’s modern middle class has served as a vital artery of modern transformation, running through the core of the nation’s major historical upheavals—from the Constitutional Revolution and Reza Shah’s modernization campaigns, to the oil nationalization movement under Mosaddegh, the industrial expansion of the late Pahlavi era, the 1979 Revolution, and the reform movement of the late 1990s.1Cyrus Schayegh, Who Is Knowledgeable Is Strong: Science, Class, and the Formation of Modern Iranian Society, 1900-1950 (University of California Press, 2009). And yet, in Iranian cinema, the lived experiences, aspirations, and inner conflicts of this class remained strikingly underrepresented until recent decades—a marginalization that sharply contrasts with its central role in the nation’s modern history.

Pre-revolutionary commercial cinema, known as filmfarsi, largely excluded the modern middle class from serious representation, whether in its “stewpot” melodrama or the “tough-guy” action films. The former, consolidated with Siamak Yasami’s Qarun’s Treasure (1965), centered on stories of love, betrayal, and sacrifice, often saturated with sentimentality, song-and-dance sequences, and overt moralizing. The latter, modeled by Majid Mohseni’s The Generous Tough (1958), focused on hypermasculine figures—typically from Tehran’s working-class neighborhoods—who upheld an informal code of justice, defended honor, and navigated the city’s criminal underworld.2Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 2: The Industrializing Years, 1941–1978 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books, 2011), 154. In both genres the life of the modern middle class remained in the shadows, while the films drew massive audiences, particularly young working-class men eager to see their desires, fantasies, and frustrations reflected on screen.3Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 2: The Industrializing Years, 1941–1978 (Duke University Press Books, 2011), 305; Filmfarsi, Documentary, directed by Ehsan Khoshbakht, 2019, Online, 84 minutes, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt9304470/.

The Iranian New Wave, or what some scholars described “alter-cinema” of the 1960s and 1970s, broke from filmfarsi’s formulaic aesthetics but remained primarily focused on the lives of marginalized groups (peasants, migrants, and workers), or on disoriented anti-heroes such as those in Dariush Mehrjui’s The Cow (1969) or Mas‘ud Kimiai’s Qeysar (1969). However, part of this movement foregrounded the dilemmas of the growing urban middle class, shaped by the expansion of higher education, the growth of white-collar employment, and the Shah’s modernization projects. For example, Mehrjui’s The Postman (1971), Nasser Taqva’i’s Tranquility in the Presence of Others (1969), and Bahram Beyza’i’s Downpour (1971) powerfully portray the identity struggles, disillusionments, and existential crises of the new middle-class.4Golbarg Rekabtalaei, “Cinematic Revolution: Cosmopolitan Alter-Cinema of Pre-Revolutionary Iran,” Iranian Studies 48, no. 4 (2015): 575-8. Perhaps the most striking example, produced in the twilight of the Pahlavi monarchy, is Abbas Kiarostami’s lesser-known film The Report (1977). The film offers an unflinching portrait of the moral and psychological collapse of a young middle-class couple. The husband, an employee of the tax office, despite holding a stable job and social position, suffers from alienation and a deep sense of meaninglessness under mounting economic pressures. His wife, unable to endure the disintegration of their family life, attempts suicide.5Parviz Jahed, The New Wave Cinema in Iran: A Critical Study (Bloomsbury Academic, 2022), 195. The film crystallizes a central motif in much of the New Wave’s engagement with the new middle class: possessing a position without possessing a horizon.

In the decade following the 1979 Revolution, cinema was initially reshaped by a state-sponsored Islamic ideology that regarded modern, secular middle-class values with deep suspicion. Representations of the cultural bourgeoisie were frequently seen as ideologically subversive and were either sanitized, marginalized, or eliminated altogether. The dominance of Sacred Defense cinema throughout the 1980s further entrenched this erasure. Despite their stark ideological differences, both pre-revolutionary commercial films and post-revolutionary Islamic cinema shared a common blind spot: the modern middle class was consistently sidelined or reduced to caricature—as weak, indecisive, emotionally unstable, or ineffectual. It remained structurally disenfranchised, culturally discredited, and narratively underdeveloped.6Kaveh Bassiri, “Masculinity in Iranian Cinema,” in Global Encyclopedia of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History (2019), 1022.

It was not until the Reform era (1997–2005) that Iranian cinema decisively shifted its gaze toward the middle class. Reform Cinema—emerging as a distinct cultural and political mode during the presidency of Mohammad Khatami—foregrounded the everyday experiences of urban middle-class life: family tensions, generational divides, ethical dilemmas, and the fragile balance between aspiration and constraint. This shift reflected broader socio-political dynamics: the expansion of the middle class in the postwar period, the relaxation of cultural restrictions, and the Reform Movement’s emphasis on civil society, citizen rights, and pluralism.7Blake Atwood, Reform Cinema in Iran: Film and Political Change in the Islamic Republic (Columbia University Press, 2016), 20-22.

Dariush Mehrjui was central to this transformation. Having earlier depicted the struggles of the lower classes, in the post-revolutionary period he turned his focus to the crises of the middle class. Films such as Hamoun (1989), Sara (1993), Leila (1996), and The Lady (1998) captured its existential dilemmas with a precision and urgency that helped define Reformist Cinema. Hamoun in particular became a touchstone, delivering what remains perhaps the most iconic cinematic exploration of middle-class existential crisis. The film traces the mental fragmentation of a man caught between revolutionary moralism, post-war fatigue, and the absurdities of modern intellectual life. Hamoun was not merely a character study; it was a cinematic diagnosis of a class that had become alienated from the system externally and eroded internally. Beyond their formal and aesthetic achievements, these films stand as cultural documents: records of a class whose fragility and inner contradictions mirror the wider dislocations of modern Iranian society. Far from marginal, the modern middle class in these films emerges as a pressure point—an affective register of Iran’s turbulent modernity.

The influence of this turn was not limited to auteur cinema. Commercial films of the late 1990s and early 2000s—such as Tahmineh Milani’s Two Women (1999), The Fifth Reaction (2003), and Ceasefire (2006), Fereydoun Jeyrani’s Red (1999), and Behrouz Afkhami’s Hemlock (1999)—likewise placed middle-class life at the center of their narratives. As William Brown has argued, these films reflected a broader cultural moment in which the middle class became the principal site for imagining social change.8William Brown, “Cease Fire: Rethinking Iranian Cinema through Its Mainstream,” Third Text 25, no. 3 (2011): 335–41, https://doi.org/10.1080/09528822.2011.573320.

This legacy extends to the present. Aida Panahi’s recent mini-series At the End of the Night (2024), independently produced and distributed through Iran’s home-video network, revisits the middle class not through philosophical allegory of auteur cinema but through intimate social storytelling. With a minimalist yet evocative style, it traces the slow erosion of middle-class life under the weight of economic collapse, institutional corruption, sanctions, and pervasive stagnation. This article argues that At the End of the Night dramatizes the emergence of Iran’s “middle-class poor,” a group defined by downward mobility amid socioeconomic precarity. Unlike earlier films that depicted explosive crises of revolution or war, the series renders the slow suffocation of daily life under inflation, housing insecurity, forced peripheralization, and emotional exhaustion. It is a portrait of decline told through silence—of a class fading not with a bang, but beneath the weight of unrelenting, invisible pressure.

The series serves as a narrative case study that makes this new dynamic visible. Its protagonists, Behnam and Mahi, are an educated young couple struggling to preserve their cultural identity and social standing under growing economic stress. They cut expenses, relocate to a satellite town outside Tehran, sell their books and paintings, and embark upon bureaucratic jobs far below their standing—all in a final bid to preserve a semblance of middle-class life. Yet, these efforts ultimately prove futile, and the family begins to unravel. At the End of the Night thus offers a tragic reflection on the fate of Iran’s middle class and the affective price of downward mobility, especially among its lower strata.

In what follows, we situate the recent socio-economic dynamics that have precipitated the impoverishment of Iran’s middle class, and examine this condition across three interlocking dimensions. First, we analyze the spatial displacement of the middle class from the city center to precarious peripheries, where geography itself becomes a marker of dispossession. Second, we trace how this displacement corrodes the moral fabric and sense of self that once anchored middle-class life. Finally, we turn to the dynamics of alienation and exclusion, showing how institutional structures and cultural norms converge to immobilize this class and deny it recognition.9While this article engages visual motifs and aspects of mise-en-scène, it does not pursue a formalist film or media studies analysis of cinematography, editing, or framing. Its focus is on plot and thematic content, examined through a sociological lens concerned with class, identity, and everyday life rather than formal aesthetics. Taken together, these sections reveal how At the End of the Night illuminates not only the everyday struggles of its protagonists, but also the structural unmaking of Iran’s modern middle class.

Figure 2: Māhī alone in bed. Still from At the End of the Night (Dar Intihā-yi Shab), directed by Āydā Panāhandah, 2024.

Contemporary Economic Crisis: The Emergence of the Middle-Class Poor

In the past decade, Iran has seen one of the most dramatic economic crises in its modern history. While the economy has long strained due to endemic issues—U.S. sanctions, systemic corruption, and structural inefficiencies—the crisis took a new and more dire course after the imposition of sweeping sanctions by the Obama administration in 2011 and the Trump administration’s 2018 withdrawal from the JCPOA (Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action), which reinstated maximum pressure policies.10Narges Bajoghli et al., How Sanctions Work: Iran and the Impact of Economic Warfare (Stanford University Press, 2024); Djavad Salehi-Isfahani, “Iran’s Economy 40 Years after the Islamic Revolution,” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, March 14, 2019, https://www.belfercenter.org/publication/irans-economy-40-years-after-islamic-revolution. These developments halted foreign investment, triggered massive capital flight—both domestic and foreign—plunged the value of the national currency, and pushed inflation toward a staggering 40%.11“Iran Inflation Rate,” accessed May 29, 2025, https://tradingeconomics.com/iran/inflation-cpi. In the past decade, these conditions have had impacts far deeper than material deprivation: they have dramatically disturbed the ethical, psychological, and identity foundations upon which everyday life rests.12Djavad Salehi-Isfahani, “Poverty and Income Inequality in the Islamic Republic of Iran,” Revue Internationale Des Études Du Développement, no. 229 (2017): 113–36.

Among the groups most deeply impacted by Iran’s ongoing economic crisis is the modern middle class. According to recent estimates, since 2012, its size has declined by an estimated 11 percent annually.13Mohammad Reza Farzanegan and Nader Habibi, “The Effect of International Sanctions on the Size of the Middle Class in Iran,” CESifo, July 3, 2024, 14-15. By “modern middle class,”14By “modern middle class” in Iran, we refer to a social group that is distinct from the “traditional middle class” or “propertied middle class” in terms of education, lifestyle, sources of income, and cultural orientation. The traditional or propertied middle class—often associated with the bazaar—has historically derived its wealth from commerce and trade, typically maintains lower levels of formal education, and has played an influential role in both the economic and political spheres of modern Iranian history, particularly in alliance with religious institutions. In contrast, the modern middle class is predominantly composed of university-educated professionals employed in white-collar occupations such as education, healthcare, bureaucracy, and the arts. See H. E. Chehabi, “The Rise of the Middle Class in Iran before the Second World War,” in The Global Bourgeoisie: The Rise of the Middle Classes in the Age of Empire, ed. Christof Dejung et al. (Princeton University Press, 2019); Ervand Abrahamian, Iran between Two Revolutions (Princeton University Press, 1982), 421. we refer not simply to an income bracket, but to a sociocultural formation characterized by higher education, relative autonomy in lifestyle, and a cultural identity rooted in symbolic distinction—particularly from the working poor. While members of this class may possess only moderate economic capital, they typically exhibit significant cultural capital in their tastes, aspirations, and everyday practices, aspiring toward a Europeanized or globalized bourgeois sensibility. Their identity is anchored less in material wealth than in markers of refinement, consumption, and cultural orientation.15Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste (Harvard University Press, 1984), 6-7, 172-175. By contrast, the working classes are generally defined by limited access to economic resources, constrained cultural capital, and a daily life oriented around subsistence and survival. While the material hardships endured by lower classes are acute and deserve attention, this article focuses instead on the psychological, social, and symbolic consequences of economic decline as they manifest within the modern middle class.

This class has emerged as one of the central casualties of Iran’s long-term economic downturn. Its dependence on fixed-income white-collar jobs—largely in the public sector, education, healthcare, and specialized services—has made its living most vulnerable to state economic policy. The state’s wage structures, often rigid and not sensitive enough to price shocks from inflation, have left salaried professionals far more vulnerable than their counterparts in the private sector.16For more information on the history of Iranian middle class’s economic ups and downs see: Sohrab Behdad, Class and Labor in Iran: Did the Revolution Matter? (Syracuse University Press, 2006). Meanwhile, economic recession, austerity measures, failed privatization, and labor market volatility have eroded stable employment and produced waves of layoffs, short-term contracts, and informal labor. One of the most significant effects of this decline has been the collapse of purchasing power, particularly devastating for a class whose identity is tightly bound to lifestyle distinction and cultural engagement. The gradual elimination of expenditures on education, leisure, and cultural goods has triggered a crisis of identity, striking at the very core of middle-class subjectivity. Recent data suggest that this loss now extends beyond cultural life to basic needs such as healthcare and housing.17Farzanegan and Habibi, “The Effect of International Sanctions on the Size of the Middle Class in Iran,” 19-20.

Because of its intermediate status and symbolic self-perception, the modern middle class is particularly susceptible to downward mobility. In recent years, austerity has worn away its more precarious layers, pushing many into lower socioeconomic brackets. As Asef Bayat noted, we are witnessing the rise of the “middle-class poor” in the neoliberal world—a group that retains the cultural memory and symbolic habitus of the middle class, but has lost its material footing.18Asef Bayat, Life as Politics: How Ordinary People Change the Middle East, 2 edition (Stanford University Press, 2013), 34. Once distinguished by distinctive consumption patterns, cultural capital, and a sense of upward mobility, this group is now economically indistinguishable from the working poor. What is more alarming is the inverse demographic trend: while the global middle class diminishes in numbers, its impoverished segment continues to expand.19Ibid., 265; Asef Bayat, “The Fire That Fueled the Iran Protests,” The Atlantic, January 27, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/01/iran-protest-mashaad-green-class-labor-economy/551690/.

Crucially, this phenomenon cannot be understood through the narrow lens of “lack of money.” Financial hardship—conventionally framed as a temporary, episodic condition triggered by job loss or unexpected expenses—presumes the backdrop of an otherwise functioning economy.20Jonathan Morduch and Rachel Schneider, The Financial Diaries: How American Families Cope in a World of Uncertainty (Princeton University Press, 2017), 4. But the downward slide of Iran’s middle class is not episodic. It is a slow-motion collapse, a long-term, structural pattern that displaces individuals from their former class status not through personal misfortune, but through the cumulative effects of a protracted, decade-long economic crisis.

Nor does the middle-class poor fit within conventional definitions of the working class. Although their material conditions increasingly resemble those of the economically disadvantaged, a clear symbolic distance remains—evident in their consumption habits, linguistic registers, social networks, and aspirational self-perceptions. What sets them apart is not their material standing, but their continued attachment to the cultural identity of the modern middle class. They continue to perform its values and aesthetics—albeit in pared-down or improvised forms. While they no longer meet the economic criteria associated with middle-class status, they remain psychologically and symbolically rooted in its worldview.

This tension of declining material conditions and persistent cultural membership is one of the defining features of their experience. The tension between dwindling resources and persistent middle-class signifiers creates a structural contradiction that shapes their everyday experience. They cannot easily sustain their membership with a middle-class ideology and refuse complete integration among the working poor. In this sense they live in a liminal state: neither solidly middle-class anymore, and not fully integrated into the subordinate classes. Understanding this in-between state is key to grasping the fluid shape of the impoverished middle class in Iran today—a condition that At the End of the Night dramatizes with striking clarity through Behnam and Mahi’s lives. Their story exemplifies how downward mobility unfolds across spatial displacement to precarious peripheries, moral erosion within the intimate sphere, and political alienation produced by institutional exclusion. These are not simply personal struggles, but structural forces shaping the everyday realities of Iran’s middle-class.

Figure 3: Pardīs town. Still from At the End of the Night (Dar Intihā-yi Shab), directed by Āydā Panāhandah, 2024.

From the City to the Non-Place: Spatial Displacement and Everyday Precarity

The first sign of the couple’s downward spiral is their departure from Tehran, less a choice than a forced migration. Their former residence in Jolfa—a historic and affluent neighborhood in northeast Tehran—offered more than economic comfort.21The neighborhood takes its name from Armenian migrants who relocated from the Jolfa district of Isfahan to Tehran in the early 20th century—a cultural lineage still evident in the area’s character today. It embodied cultural density: tree-lined streets, bookstores, galleries, reputable schools, and a sense of visibility and belonging. It was a lifeworld where daily rhythms sustained both identity and community.

Under the pressure of inflation and mounting living costs, Behnam and Mahi are pushed to leave this world behind for Pardis, a satellite town on the mountainous outskirts of Tehran. Composed of monotonous high-rises from the Ahmadinejad-era Mehr Housing Project, Pardis lacks the basic foundations of urban life: walkable streets, public amenities, and spaces of sociability. Their move is not simply geographic but symbolic: a descent from center to margin, from meaning to anonymity. Ownership here is stripped of dignity, reduced to a bare apartment in a failed housing scheme. Pardis resembles a dormitory settlement rather than a city: a place to rest, not to live.

In Jolfa their home was embedded in networks of cultural and intellectual life. In Pardis it becomes a container for fatigue. Each day they travel into Tehran for work and school, returning at night to a periphery emptied of memory and future horizons. In an early episode, Behnam lashes out in a monologue summarizing the pressures of his new reality:

I have to wake up three hours earlier every morning. In the evening, I drag that kid through three hours of traffic—crowded buses, packed metros. By the time I get home, it’s already seven. If I try to read a single page or sketch a design, it’s midnight. And then I lie awake thinking about this goddamn apartment’s mortgage. I haven’t slept like a human being in five months.22t the End of the Night, Episode 1, 00:32:36-00:33:04.

Life in the periphery has stripped him of the place, energy, and community necessary for creative work. As anthropologist Setha Low argues, space becomes “place” only through social relations.23Setha Low, Spatializing Culture (Routledge, 2017), 32. From this vantage point, to be pushed to the periphery is thus to endure not only economic precarity but cultural erasure. It is to live without connection, recognition, or promise.

This negation is intensified inside the home. In Pardis, the home ceases to be a sanctuary and becomes a prison. With exterior life absent, the weight of despair and inertia collapses inward. Marc Augé calls such places “non-place,” sites stripped of history, identity, and relation.24Marc Auge, Non-Places: An Introduction to Supermodernity, trans. John Howe (Verso, 2008), 77-78. Pardis, in this sense, is not an extension of the city but its opposite: a concrete landscape of de-socialization, where existence is reduced to endurance. In this vacuum the home becomes a pressure chamber, overburdened with the emotional labor of replacing a vanished public sphere. Sleeplessness, resentment, and existential fatigue replace intimacy and rest. Behnam’s insomnia, his disorientation, and Mahi’s weary pragmatism all register the psychic toll of life in a non-place.

The series visualizes this collapse through its mise-en-scène. Across the nine episodes only a handful of scenes take place in “living” urban space. In Pardis, exterior life is marked by friction or futility—Behnam’s mistaken detention on a shuttle bus, a quarrel with a neighbor, a scuffle in a barren field. The narrative is largely confined indoors, where windows open onto barren cliffs, walls press in suffocatingly, and conversations dissolve into silence. The grinding of coffee beans each morning becomes a sonic motif for the grinding-down of bodies and relationships. When Behnam hurls the grinder out the window, the act reads not as mere frustration but as expulsion—an attempt to cast off accumulated futility and class rage.

Figure 4: Bihnām grinding breakfast coffee. Still from At the End of the Night (Dar Intihā-yi Shab), directed by Āydā Panāhandah, 2024.

In contrast, Tehran retains a spectral aura of possibility. Work, school, and fleeting moments of pleasure remain tethered to the city. In one of the series’ most revealing confrontations, Behnam, desperate and disoriented, pleads with Mahi: “Our life is headed somewhere awful. Let’s sell this place and move back to Jolfa. This place isn’t for us. These mountains, these highways—they’re driving me crazy. I’m sick of myself. I’m sick of my life.”25At the End of the Night, Episode 1, 00:46:14-00:46:53. His words are not just a cry for change; they are an elegy for the failure of “home” without “city,” for the middle class’s vanishing ability to make space meaningful. The mountains and highways of Pardis, stripped of texture or memory, stand as monuments to the anti-urban. It is the condition Milan Kundera famously described as the “unbearable lightness of being,” the very novel that recurs throughout the series as a visual and thematic touchstone. Or, as Behnam bitterly names it, “this godforsaken wilderness” (in barr-e biabun-e la’nati).26At the End of the Night, Episode 1, 00:46:55-00:46:55. Their conflict—on the surface, about whether to stay or leave—is, at its core, a struggle between two competing survival strategies. For Mahi, homeownership, even in a dystopia, is a bulwark against inflation;27At the End of the Night, Episode 1, 00:46:23-00:46:27. for Behnam, it is despair itself. Their dispute crystallizes the dilemma of the middle-class poor: whether to prioritize fragile economic security or to reclaim cultural identity in the city.

The move from center to periphery, then, is more than geographic, it is existential. As urban life contracts, pressure turns inward, corroding the moral fabric and destabilizing the sense of self that once anchored the modern middle class. The following section turns to this inner unraveling, tracing how economic strain and spatial displacement crystallize into moral erosion.

Moral Erosion: The Fragility of the Middle-Class Self

The economic collapse of Iran’s modern middle class in recent years has not been confined to income, livelihood, or forced relocation to peripheral satellite towns. Its reverberations extend deep into the very conditions that sustain social networks. As Pierre Bourdieu argues, the reproduction of social capital—“the aggregate of the actual or potential resources linked to possession of a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition”—is inseparable from both economic and cultural capital.28Pierre Bourdieu, “The Forms of Capital,” in The Sociology of Economic Life, ed. Mark Granovetter and Richard Swedberg (Routledge, 2011), 84. When the material foundations of capital are undermined by inflation, job insecurity, and prolonged stagnation, the capacity to invest in and maintain networks of kinship, friendship, and civic association is correspondingly diminished. What deteriorates under such conditions is not merely participation in formal organizations, but the resources and practices that make durable social ties possible—trust, reciprocity, and shared norms—thereby constraining the collective benefits these networks once generated.29Scholars have shown that neoliberal policies—such as job insecurity, deregulation, declining real wages, and growing economic inequality—have played a decisive role in the erosion of trust, collective solidarity, and social cohesion. See, for example, David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism (Oxford University Press, 2020); Richard Sennett, ed., The Culture of the New Capitalism (Yale University Press, 2007).

At the End of the Night captures these dynamics on an intimate scale. From its opening episodes, the erosion of communal trust and solidarity is visible in the unraveling relationship between Behnam and Mahi. What begins as low-level domestic tension escalates into a broader disintegration of the social fabric around them. In episode two, for instance, an argument erupts over Mahi’s frugality—taking buses instead of taxis and limiting food purchases to stay afloat financially. To Behnam these “austerity measures” distort the natural rhythm of their shared life, hollowing out its texture.30At the End of the Night, Episode 1, 00:47:42-00:47:43.

This conflict soon spills over into Behnam’s relationship with their son, Dara. In several scenes Behnam loses patience over Dara’s schoolwork, yelling with such intensity that the child retreats in fear and hurt. The radius of dysfunction expands. Behnam’s previously respectful rapport with Mahi’s family collapses. In a jarring moment, Mahi’s father assaults Behnam with a steering wheel lock in front of Dara’s school—an act of symbolic and literal violence under the watchful gaze of other children and parents. Mahi’s own relationship with her father begins to fracture. In a fit of rage, he slaps her across the face, an unprecedented act that betrays the affectionate, dignified image he had cultivated as a single father. Even Mahi’s close relationship with her sister begins to unravel under the pressure of financial disputes and emotional fatigue.

These fractures are not simply the product of personal failings. They are structural responses to prolonged, grinding crisis. The economic strain has become so pervasive that it has normalized aggression and destabilized moral restraint. Characters behave in ways alien to their prior selves, later bewildered by the very actions they performed. Introspection brings little clarity, because the behaviors in question are not rooted in individual pathology, but in systemic exhaustion. The line between morality and survival begins to blur.

Figure 5: Interrogation of Bihnām. Still from At the End of the Night (Dar Intihā-yi Shab), directed by Āydā Panāhandah, 2024.

This moral breakdown reaches its peak in moments when characters abandon the ethical boundaries they once upheld. In one storyline Behnam plots to strip Mahi of her maternal rights by conspiring with a friend to fabricate evidence for a custody battle. Though morally conflicted he eventually goes through with it. In another plot narrative he begins a sexual and emotional relationship with Soraya, a divorced neighbor. He knows the affair is emotionally unsustainable and socially asymmetrical—he is emotionally fragile, and she is vulnerable and positioned on a lower rung of the class hierarchy. Yet he continues the relationship, less out of desire than to fill the void left by Mahi. These entanglements are not simply personal failures; they are symptoms of a larger moral exhaustion, born from years of economic and social degradation. What social psychologists describe as “the erosion of self-regulation,” “increased aggression,” and “moral disengagement” is here rendered in compelling narrative form. Human relationships in At the End of the Night become mirrors of a society in which social capital is eroding and moral frameworks are fraying at the seams.

Figure 6: Safā, Bihnām and the Gulag painting. Still from At the End of the Night (Dar Intihā-yi Shab), directed by Āydā Panāhandah, 2024.

Perhaps the most dramatic illustration of this collapse occurs in episode four, in a scene that distills the moral stakes of the entire series. Behnam, Mahi, and Safa—a family friend and a renowned painter recently returned from Europe—become embroiled in a dispute over a painting. Once gifted by Safa as a gesture of friendship, the artwork is now treated as property, a survival asset. All three are in financial distress, and each now claims ownership. What once functioned as a symbolic expression of cultural and moral generosity has been stripped of its meaning and reduced to an object of transaction. Safa, at first hesitant, awkwardly asks for the painting back: “I know I gave it to you as a gift, but I’ve come regretfully to reclaim it.”31At the End of the Night, Episode 3, 00:47:19-00:47:26. When Behnam and Mahi resist, he becomes more forceful: “I gave it to you, and now I want it back. Among artists, this is normal.”32At the End of the Night, Episode 3, 00:53:45-00:53:51. Their refusal is less about principle than about necessity. They plan to sell the painting to alleviate their worsening financial situation. Safa, stung, exclaims: “I gave you that painting to hang in your home, not to sell. Doesn’t it feel parasitic to turn my pain into your bandage?” Behnam replies coldly: “No, it doesn’t. It’s mine. It’s payment for all the work I did for you to hold your first gallery in Iran.”33At the End of the Night, Episode 3, 00:52:41-00:52:54. This moment even shocks Mahi. The Behnam she once knew—principled, sensitive, morally grounded—has become transactional, detached, unrecognizable. She pleads: “Give it back. It’s beneath us to beg like this.” Behnam responds: “Maybe it is for you, but not for me. I’ve been humiliated more in these past months than in my whole life. This is just one more.”34At the End of the Night, Episode 3, 00:49:57-00:50:08.

Figure 7 (left): The Gulag Painting. Still from At the End of the Night (Dar Intihā-yi Shab), directed by Āydā Panāhandah, 2024.

Figure 8 (right): Safā and Bihnām looking at the Gulag painting. Still from At the End of the Night (Dar Intihā-yi Shab), directed by Āydā Panāhandah, 2024.

The irony of the scene lies in the painting itself: The Gulag Archipelago, named after Aleksandr Isaevich Solzhenitsyn’s harrowing account of moral disintegration in the Soviet labor camps. In the original book, not only the state but the prisoners themselves betray each other for survival, illustrating how prolonged crisis degrades human dignity.35Aleksandr Isaevich Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago, 1918-1956: An Experiment in Literary Investigation, trans. Thomas P. Whitney (Harper & Row, 1974). Here, the artwork becomes the battleground for a similar moral unraveling. The scene reaches its climax when Safa and Behnam stand side by side, facing the painting. The camera adopts the painting’s point of view, positioning the two men in a confrontational medium close-up. Safa, solemn and theatrical, quotes a line from Solzhenitsyn:

The same hands that once chained ours now reach out in reconciliation, saying: ‘No! The past should not be unearthed!’ Anyone who brings up the past should lose one eye. But as the saying goes: ‘those who forget the past should lose both.’36At the End of the Night, Episode 3, 00:50:20-00:50:49.

Safa invokes the quote to justify reclaiming the painting and reiterates the symbolic meaning of his earlier act of generosity. But Behnam remains unimpressed and retorts: “I agree. Both eyes should go.”37At the End of the Night, Episode 3, 00:50:50-00:50:53. The reply is biting and laced with cold irony. While seemingly endorsing Safa’s moral lesson, Behnam reverses the script and insinuates that Safa’s appeal to morality is simplistic and irrelevant in the situation.

This dispute over art, morality, and ownership stands as a compressed allegory of a greater crisis. This is how symbolic capital—the accumulation of honor, prestige, and social recognition—becomes null in economic stress, how generosity becomes transactional, and how dignity succumbs to survival. The viewer is not merely compelled to witness the erosion in morals of the characters but to grasp the underlying system that drives their erosion. What we are being presented with is not a crisis in consumption or standard of living downturn. This is a breakdown that shrinks horizons in care, trust, and possibility. A class that once mediated between state and society, particularly during the reform era, is now compelled to watch from the sidelines. The modern middle class that once drove dialogue, critique, and imagination is increasingly fettered—trapped in material poverty and yet in moral fatigue. This is perhaps one of the most profound and least visible consequences of Iran’s ongoing economic crisis.

This internal unraveling does not occur in isolation. The moral fragility of the middle class is reinforced by external pressures of political marginalization and social exclusion, forces that strip it of recognition and constrict the space for agency. The following section turns to these dynamics, examining how the state’s disciplinary apparatus and society’s cultural codes together entrench the precarious condition of the middle class.

Alienation and Exclusion: The Politics of the Middle Class

Iran’s modern middle class occupies a precarious position in the country’s sociopolitical landscape. Under the Islamic Republic, this class is traditionally viewed as representative of a secular way of life and a tendency for Western values, all characteristics that are fundamentally at odds with the regime’s religious-revolutionary hegemony. As such the modern middle class has been cast as an ideological “other”—a group in need of discipline, surveillance, and, when necessary, exclusion. This suspicion manifests in various forms: lifestyle and dress policing, restrictions on cultural expression, and systematic barriers to meaningful institutional participation. Over time these pressures marginalized the modern middle class across both bureaucratic structures and public discourse. In the unwritten grammar of the government, ideological loyalty consistently takes precedence over professional competence—what the regime valorizes as ta’ahhod (commitment) over takhassos (expertise). Those failing in this regard are not merely overlooked; they are stalled, sidelined, or purged from the machinery of state power.

In At the End of the Night Behnam stands as a paradigmatic figure of institutional marginalization. Once a respected artist and university lecturer, he now has the absurd title “urban waste specialist” (karshenas-e zava’ed-e shahri) in Tehran Municipality’s Beautification Office—a title that literally captures his professional relegation. For years Behnam has awaited a promotion, but his requests are either ignored or indefinitely deferred. A revealing scene with his boss—a younger, ideologically aligned, and religiously observant manager—lays bare the internal logic of the system. Behnam is not evaluated based on his expertise or creative contributions, but rather on his ideological conformity and personal life. After learning that Behnam is divorced, the manager insists Behnam remarry and explains that marital status is a prerequisite for promotion. “Having a family [meaning being married],” he states, “is one of the conditions for becoming a model boss” (modir-e taraz).38At the End of the Night, Episode 4, 00:29:20-00:29:23. The absurdity is telling. Competence and innovation are not the criteria for professional advancement, but rather conformity with the moral and ideological expectations of the state.

The Beautification Office, which exists to promote urban aesthetics, is rendered in the series as a stifling, bureaucratic apparatus—one that demands obedience over innovation and aesthetic conformity over artistic exploration. In one pivotal scene, Behnam gets into a physical confrontation with a shopkeeper who refuses to remove his family’s handcrafted storefront sign. The municipality wants to replace all signage with state-approved templates, enforcing a visual order in harmony with an abstract, top-down ideal of uniformity. The clash dramatizes a deeper tension between citizen-centered aesthetics—rooted in memory, craftsmanship, and autonomy—and the homogenizing, ideological vision of state-sponsored “beauty.”

Mahi’s experience mirrors Behnam’s. A young woman with leadership skills and a long-standing background in art, she is confined to a low-level position at the Niavaran Cultural Center. Frustrated, she tells her supervisor: “I’m rotting in this basement. I have to leave. I’ve been doing a job I hate for ten years. My life is slipping away.”39At the End of the Night, Episode 4, 00:27:30-00:27:55. Once an aspiring student of art with dreams of studying in France, Mahi now coordinates exhibition schedules for others. The space offers neither creative freedom nor professional autonomy; it functions instead as a filtration mechanism—an administrative checkpoint for legitimizing content that aligns with the regime’s cultural code.

For women like Mahi, the pressure to conform is doubly intensified. Mahi’s attire visibly shifts across spaces. At work she wears a black manteau and headdress (maqna’eh). Outside, she switches to a lighter shawl. This change is not simply sartorial; it is a symbolic act of resistance, a brief gesture of reclaiming autonomy in the face of institutional discipline. The contrast suggests a deeper tension: women like Mahi, who comply out of necessity rather than conviction, are barred from advancement. The vetting system—designed to enforce ideological conformity—either filters such individuals out during hiring or immobilizes them within the lower echelons of bureaucracy.

Figure 9: Māhī at her workplace. Still from At the End of the Night (Dar Intihā-yi Shab), directed by Āydā Panāhandah, 2024.

The cultural center where Mahi works—like the Beautification Office where Behnam is employed—stands in stark contradiction to its mission. One is tasked with nurturing art but reduces it to state-approved spectacle; the other is charged with enhancing the city’s beauty but enforces an antiseptic, controlled aesthetic devoid of local expression. In both institutions professionals are not empowered agents of creativity, but passive functionaries, entrapped in bureaucratic repetition. Promotions are tokens for ideological loyalty rather than rewards for skill.

In this reading bureaucratic alienation is not merely an individual misfortune; it is a structural mechanism. A system designed to suppress or marginalize those deemed culturally alien or politically suspect. The result is a double alienation: the state sees the modern middle class as a threat to its ideological order, while the modern middle class, confronted by institutional stagnation, economic mismanagement, and cultural censorship, comes to see the state as the architect of its disempowerment. What emerges is a chronic condition of mistrust—a structural disconnect that erodes the social contract and jeopardizes national cohesion. The professional experiences of Behnam and Mahi reflect more than workplace frustration. They register an existential condition—a world in which expertise is subordinated to obedience, and those who once shaped public life are now managed by the ideologically trustworthy. This alienation is not confined to the office; it spreads across the landscape of social life, becoming part of the emotional architecture of everyday life.

In addition to the political alienation imposed by the state, Iran’s modern middle class has long been subject to a parallel form of social exclusion from below. This marginalization does not primarily stem from economic difference, but rather from perceived distinctions in lifestyle, worldview, and appearance. Since its emergence in the late nineteenth century, the modern middle class—comprised of artists, intellectuals, writers, students, and academics—has been cast as a social outlier by traditionalist segments of Iranian society. It has repeatedly appeared as the “rejected other,” marked by symbolic violence: through pejorative terms like zhigol, fokoli, and soosool (dandy, pretty boy, softie), and through belittling representations in literature, cinema, and public discourse.40Hamid Naficy traces the development of the zhigol, fokoli, and soosool character types in pre-revolutionary filmfarsi as emblematic of Iran’s cultural anxieties about modernity and masculinity. These figures—often portrayed as effeminate, Westernized, and morally suspect—served as foils to the hypermasculine jahel or lat characters who defended traditional codes of honor and authenticity. The fokoli in particular, usually dressed in European clothing and fluent in foreign languages, symbolized a class perceived as culturally alienated and socially pretentious. Through these caricatures, filmfarsi reinforced popular suspicion of the modern middle class and reflected broader social tensions between tradition and modernity. Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 2, 261–87. The result is a condition of cultural marginalization—a position in which the modern middle class is not only politically constrained but also denied full cultural legitimacy. In such a landscape, cultural actors from this class experience double estrangement: from the top-down repression of the state, and from the bottom-up ridicule of traditional society. Caught between institutional repression and symbolic denigration, the modern middle class occupies a profoundly unstable and embattled social position.

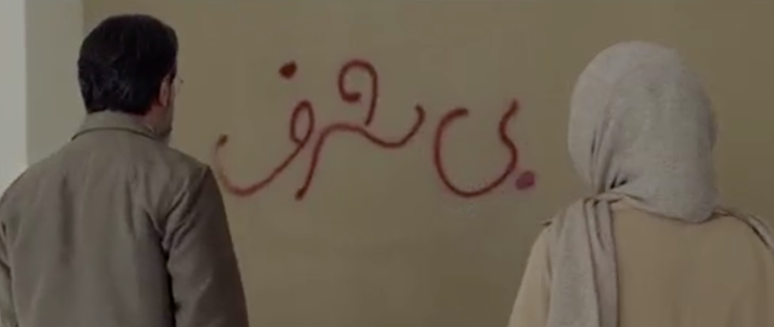

At the End of the Night renders this condition tangible through the figure of Behnam, who is repeatedly subjected to acts of social humiliation and moral judgment. A particularly visceral instance occurs when Soraya’s ex-husband, upon discovering Behnam’s relationship with her, spray-paints the word “dishonorable” (bi-sharaf) in bold red across his living room wall.41At the End of the Night, Episode 6, 00:27:02-00:27:22. The act, saturated with patriarchal notions of namus (honor), is not just an expression of jealousy; it is an assertion of traditionalist moral authority against a man whose lifestyle violates its codes.

But instead of erasing the insult, Behnam transforms it. He picks up his paintbrush—not to conceal, but to sublimate. He scribbles over the slur and builds a dark background around it, turning the wall into a site of expression. The result is not a conventional artwork, but a furious composition: a deformed, wounded face with sunken eyes, executed in violent strokes of red, blue, and black. It is an abstract expressionist outcry—a psychically saturated self-portrait of collapse. The wall itself becomes canvas, confession, and an aesthetic defiance, transforming trauma and humiliation into a gesture of creation. Behnam’s brushwork, echoing the disfigured subjects of Egon Schiele,42In episode four of the series, Reza—Mahi’s former classmate—accuses Behnam of imitating Egon Schiele, the acclaimed early 20th-century Austrian painter. Indeed, Behnam’s mural bears certain affinities with Schiele’s distinctive style. Known for his expressionistic intensity and psychological rawness, Schiele’s work is characterized by agitated lines, contorted bodies, and emotionally unstable figures. His paintings—particularly his stark depictions of the nude—offer a harsh, vulnerable, and often disoriented vision of the human form, serving as a critique of the conservative, moralistic hypocrisy of fin-de-siècle Austrian bourgeois culture. By confronting official aesthetics and rendering the body with unflinching attention to decay, mortality, and inner turmoil, Schiele challenged the idealized human image promoted by academic art. His oeuvre emerges as a deeply personal articulation of identity crisis and the fragmentation of modern values. challenges both the aesthetic ideals of official culture and the moralism of patriarchal society. It performs a quiet rebellion against the normative image of the strong, dignified, self-controlled Iranian man. Here, vulnerability is not hidden but exposed; woundedness elevated into form.

Figure 10: Slur written on the wall of Bihnām’s apartment. Still from At the End of the Night (Dar Intihā-yi Shab), directed by Āydā Panāhandah, 2024.

Figure 11: Bihnām painting over the slur. Still from At the End of the Night (Dar Intihā-yi Shab), directed by Āydā Panāhandah, 2024.

The mural is more than a symbolic act of resistance. It is an indictment. A confrontation with all those who have diminished him: the wife who abandoned him, the supervisor who humiliated him with menial assignments, the former student turned into romantic rival, and the man who literally branded him as dishonorable. The painting becomes a visual condensation of all that Behnam has endured—a compression of shame, rage, and unspoken grief.

Even Mahi’s father—himself a retired worker from the film industry and familiar with art—views Behnam with barely veiled contempt. He describes him in ridicule as “a tired Paul Newman with a dead battery”43At the End of the Night, Episode 1, 00:28:06-00:28:17.—a once-charming intellectual now seen as useless and drained. This disdain is echoed by Behnam’s subordinates, who regard him not with respect, but with pity—an overeducated man unable to navigate the practical demands of daily life. Even his encounter with the shopkeeper, who resists Behnam’s municipal directive to replace a traditional signboard, reflects this social dynamic. To the shopkeeper, Behnam is not a bearer of refined aesthetics, but a disconnected bureaucrat, a symbol of superficial modernity out of touch with vernacular tradition.

What Behnam suffers is not simply the bitterness of a failed career or broken relationships. It is the long historical wound of a class whose cultural and symbolic authority has been steadily eroded. His marginalization is not merely psychological; it is structural. He is not only a character, but a vessel of collective memory, a condensation of the traumas, contradictions, and exclusions that have haunted Iran’s modern middle class for generations.

Figure 12: Bihnām and his supervisor. Still from At the End of the Night (Dar Intihā-yi Shab), directed by Āydā Panāhandah, 2024.

Conclusion: Shattered Lives, Fading Horizons

Beneath the surface of domestic drama, At the End of the Night offers a layered commentary on the unraveling of Iran’s modern middle class. Through narrative structure, character development, and visual composition, it charts the erosion of stability once secured by prosperity, civic participation, and cultural production. What emerges is not only the intimate story of Behnam and Mahi, but a broader portrait of a class marked by downward mobility, forced precarity, and the exhaustion of daily survival.

As this article has argued, the series crystallizes the paradox of Iran’s “middle-class poor”: a group slipping into economic decline while still clinging to the cultural identity and aspirations of the middle class. It depicts with rare sensitivity the fragility of this condition—its contradictions, deferred dreams, and fading horizons.

In this sense, At the End of the Night stands as more than a tale of personal despair. It is a cinematic elegy for a class that once imagined itself the engine of national progress, and now finds itself estranged from the state, displaced from the cultural mainstream, and depleted by the daily labor of survival. It no longer dreams of the future; it clings to the remnants of the present. And in that quiet endurance, it becomes a witness to its own fading past. Beyond its immediate story, the series compels us to reconsider the place of the middle class in contemporary Iranian cinema and to recognize how cultural forms register not only political upheaval but the quieter, more corrosive collapse of everyday life.

Cite this article

While the middle class in Iran has historically defined itself not solely by income but through cultural consumption, lifestyle practices, and symbolic distinction from the working poor, recent structural crises have produced a new social formation: the middle-class poor. This group, despite facing severe economic decline due to inflation, corruption, mismanagement, and international sanctions, continues to identify culturally and symbolically with its former class position. Its members retain the aspirations, aesthetic dispositions, and social sensibilities of the middle class, even as their material conditions increasingly resemble those of the lower class.

This article analyzes the 2024 mini-series At the End of the Night (Dar Entehā-ye Shab), directed by Ayda Panahi, as a narrative case study that dramatizes this condition. Through a close reading of the series’ portrayal of a middle-class couple confronting economic collapse, professional marginalization, and emotional fragmentation, the article explores how the tension between economic precarity and cultural continuity gives rise to a distinct, liminal social identity. We argue that this impoverished middle class is not merely a class in decline, but a class caught in transition—alienated from its past, dislocated in the present, and uncertain about its future.