The Representation of Drugs in Iranian Arthouse Cinema and Their Social Context (2000-2025)

Figure 1: Still from Critical Zone (Mantaqah-yi buhrānī), directed by ‘Alī Ahmadzādah, 2023.

The Rise of the Social Issues “Genre” in Cinema Under Muhammad Khātamī’s Reformist Presidency

In 1999 a seminal conference on Iranian cinema was held at the School of Oriental and African Studies, London. In a paper delivered there and subsequently published as The New Iranian Cinema: Politics, Representation and Identity, Ali Reza Haghighi noted of the contemporaneous situation in Iranian cinema that although it was heavily affected by politics, the films themselves could not explore political issues. He claimed that in spite of this restriction many films could still be interpreted as political in intent.1Ali Reza Haghighi, “Politics and Cinema in Post-revolutionary Iran: An Uneasy Relationship,” in The New Iranian Cinema: Politics, Representation and Identity, ed. Richard Tapper (London: Taurus, 2002) 109-116. The conference occurred two years after the election of a Reformist government, under the presidency of Muhammad Khātamī, during which there was some relaxation of censorship in cinema. As Blake Atwood has summarised it, “Starting in the early 1990s an intimate relationship developed between the popular reformist movement and the film industry.”2Blake Atwood, “Introduction: Revolutionary Cinema and the Logic of Reform,” in Reform Cinema in Iran: Film and Political Change in the Islamic Republic (New York Chichester, West Sussex: Columbia University Press, 2016), 10. Changes became evident within a few years as filmmakers explored the (limited) new freedoms. Yet some twenty-five years later both everything and nothing has changed.

One significant change was the introduction of sīnimā-yi muslihānah or social issues filmmaking as an official “genre” in the Islamic Republic. 3Whether or not this qualifies as a genre has been debated, but for simplicity it will be classified as such here. Saeed Zeydabadi-Nejad has cited an unpublished document from the Ministry of Cultural and Islamic Guidance (MCIG) in which the genre was defined as “films with ‘reformist intentions’ which would focus on social, political and cultural problems.”4Saeed Zeydabadi-Nejad, The Politics of Iranian Cinema: Film and Society in the Islamic Republic (London: Routledge, 2009), 50. A significant marker was 2000, when these emerging changes to the industry were acknowledged internationally and became measurable through prestigious awards.5Three new or early career Iranian filmmakers, Ḥasan Yiktāpanāh, Samīra Makhmalbāf and Bahmān Qubādī, won major awards at Cannes. More controversial on the home front and more successful internationally was Panāhī’s The Circle (Dāyirah) which won a Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival later that year. All films were purchased for international distribution. This prompted Hamid Dabishi, who described the situation as “a spectacular achievement for Iranian cinema,” to write prematurely of the “death of ideology in Iranian political culture.” This prompted Hamid Dabashi to write prematurely of the “death of ideology in Iranian political culture.”6Hamid Dabashi, “Whither Iranian Cinema? The Perils and Promises of Globalization,” in Close Up: Iranian Cinema Past, Present and Future (Verso, London & New York, 2001), 244–282. Nonetheless film critic Houshang Golmakani noted in his roundup of films from 2000 – 2001 that the biggest of these changes had been the filmic exploration of political content.7Houshan Golmakani, “Stars within Reach.” in Being & Becoming: The Cinemas of Asia. eds. Aruna Vasudev, Latika Padgaonkar and Rashmi Doraiswami (New Delhi: Macmillan India, 2002), 186–204. Although social issues films enjoyed official recognition, there was an inherent contradiction. While social issues films may be critical of the realms in which they are set, such as the home, they must tow the regime’s interests. Thus, it has been difficult for filmmakers to find the ever-shifting red line in showing or suggesting the social roots of personal problems, as they often reflect poorly on government.

A major social problem in Iran has been the use of drugs. Although drug use is seemingly a personal issue, I argue that it is not disconnected from government policy. In this article I trace the history of the representation of drugs as addressed by arthouse directors in what became one of the important ‘genres’ of the Islamic Republic. I justify my argument with several key films made between 2003 and 2025, discussing their reflection of contemporary social debates, changes in policy and legislation, and the economic situation.8Peter Decherney and Blake Atwood note the complications of differentiating between mainstream and art cinema in Iranian cinema, using William Brown’s article “Cease Fire: Rethinking Iranian Cinema through Its Mainstream,” a film directed by Tahmīnah Mīlānī. The gist of their argument is that work such as Milani’s tackles controversial issues like gender and most recently AIDS [and thus] falls into Hamid Naficy’s category of “art cinema” because it “engages with [post-revolutionary] values” and critiques “social conditions under the Islamicgovernment.” See Peter Decherney and Blake Atwood, “Introduction,” in Iranian Cinema in a Global Context: Policy, Politics, and Form, ed. Peter Decherney and Blake Atwood (New York: Routledge, 2015), 7 and footnote 36. Over time, much genre hybridization can be observed, in line with global trends in contemporary cinema.9“Genre” as a term is used very loosely here. What constitutes genre in Iranian cinema is as difficult to define as the terms “mainstream” and “art cinema”, discussed in the following footnote. It has been claimed that Sacred Defence cinema is the only true Iranian genre. In examining the representation of drugs in social issue films, we find that the hybridization of genres has evolved over time, with the initial use of melodrama shifting to thriller, crime, action, and police procedural modes. Additionally, the setting has shifted from the middle class to the working class and back again. I will argue that these changes can be attributed to two external reasons ⸺changing politics and the Iranian economic crisis.

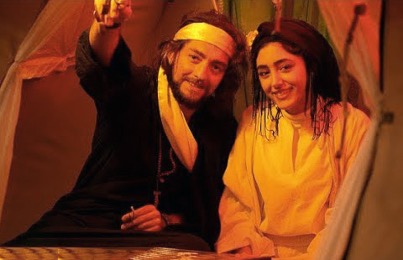

Figure 2: Still from Critical Zone (Mantaqah-yi buhrānī), directed by ‘Alī Ahmadzādah, 2023.

Although social issues films came to be a trademark of Iranian post-revolutionary cinema, its birth can be traced to the so-called New Iranian Cinema in the 1960s.10See Parviz Jahed, “The Forerunners of the New Wave Cinema in Iran,” in Directory of World Cinema: Iran. ed. Parviz Jahed (Bristol: Intellect, 2012), 84–91. Jahed claims 1969 as the starting point, while others argue for an earlier date, around 1962. A prominent and controversial feature was Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī’s The Cycle (Dāyirah-yi Mīnā) produced in pre-revolutionary Iran in 1974, but initially banned for release. The Cycle revolves around a young man attempting to raise money for his father’s medical treatment and is set largely within the confines of a large government hospital where organized gangs sell adulterated blood to impoverished patients. That a film must uphold the incorruptibility of the regime was true of both pre-revolutionary and post-revolutionary cinema, and so The Cycle was not released in Iran until 1978, following the establishment of a blood bank in Iran and after premieres of the film in Europe. It set what would become a common pattern for the controversies surrounding independent social issues productions in the Islamic Republic.

On my annual visits to the Fajr International Film Festival between 2001 and 2018, I discussed the films with other regular international guests. Some of us noticed that in each edition of the festival a specific theme would emerge among the films selected for our viewing. Polygamy and temporary marriage, for example, were themes that seemed to recur when the Family Laws were under debate in Parliament. At one point, I asked Amīr Isfandiyārī, who was in charge of International Affairs at the Fārābī Cinema Foundation at the time, about an observation I had made: that the selection of films, which seemed more arthouse than commercial, appeared to be connected to contemporary social issues. When queried whether this was related to funding, he commented that although I was not the first to ask this question, it was not the case. Unconvinced, I began to discuss the connections between funding and topics with independent filmmakers.11In 2014, I encountered an extreme example in a never realised project being pitched. It combined what seemed an unlikely mix of Bob Dylan and Jimi Hendrix with Sacred Defence. The filmmaker slightly shamefacedly conceded that this was for funding appeal.

Figure 3: Still from The Cycle (Dāyirah-yi Mīnā), directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī, 1974.

Drug Representations in Film

Illegal drug use and addiction have long been one of Iran’s most pressing social issues. In the late 1990s, Khātamī introduced reforms, both reducing penalties for drug use and increasing methadone maintenance treatment, but neither survived the Ahmadīnizhād presidency. Estimates of drug abuse in Iran vary. The Islamic Republic of Iran Drug Control Headquarters claimed that 2.8 million people suffered from addiction in 2017, shortly before the production dates of two films explored further on, Sheeple (Maqz’ẖā-yi kūchak-i zang’zadah, 2018) and Just 6.5 (Mitrī shīsh u nīm, 2019).12“Iran’s drug problem: Addicts “more than double” in six Years,” BBC news, June 25, 2017. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-40397727 Also in 2017, Hasan Nawrūzī, spokesman for the Majlis Judicial and Legal Commission, stated that more than six million people were involved in drugs in the country, including 5.2 million addicts and 1.8 million users.13“Iran: Drug Law Amended to Restrict Use of Capital Punishment,” Global Legal Monitor, August 31, 2017. Library of Congress Digital Collections. https://www.loc.gov/item/global-legal-monitor/2017-08-31/iran-drug-law-amended-to-restrict-use-of-capital-punishment/. It is generally agreed that these statistics are underestimated, along with the numbers of narcotics traffickers who have been executed in the last three decades. The impact, not reflected in these statistics, also extends to the significant number of narcotics agents who have died in the line of work.

Pūrān Dirakhshandah, an “insider” filmmaker and self-proclaimed social issues filmmaker, made a 17-part documentary called Shukarān between 1980 and 1982 about drug addiction, smuggling, and methods of preventing drug abuse. However, all the other films that I reference are fictional. During the Khātamī presidency, Dirakhshandah’s Candle in the Wind (Sham‘ī dar bād, 2003), a classic social issues film, introduced a theme involving parties and drug use that would become a recurring motif in later works, even though this theme appears only briefly in this film. This theme would resurface as a narrative device in many films, including Ja‘far Panāhī’s Crimson Gold (Talāy-i Surkh, 2003), also released in 2003, and Mustafā Kiyā’ī’s Ice Age (‘Asr-i Yakhbandān, 2015), which will be discussed further.14Ja‘far Panāhī is also a self-described Social Issues filmmaker.

Early in the Ahmadīnizhād presidency, two major examples of films where drug addiction is a major plot element were produced: Rakhshān Banī-I‘timād’s Mainline (Khūn’bāzī, 2006) and Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī’s Santūrī (2007). These two arthouse films were widely screened internationally. They both portray addiction in young middle class Tehrani characters, and the destruction that it causes to their personal lives and relationships. They are harrowing examples of melodrama, which had a strong presence in Iranian social issues films at the time.

Mainline deals with a young woman whose addiction eventually ruins her marriage prospects with her diasporic Iranian fiancé, despite the efforts of her mother to help her come clean. Mainline was approved for domestic and international screenings, despite, as Michelle Langford notes, that it “brazenly and cleverly flaunt[s] censorship regulations.”15Michelle Langford, “Mainline,” in Directory of World Cinema: Iran. ed. Parviz Jahed (Bristol: Intellect, 2012), 165. Roxanne Varzi learned from an interview with Banī-I‘timād’s script co-writers that inspiration for the film came fromBanī-I‘timād’s discovery that the drug problem was reaching the middle classes.16Roxanne Varzi, “A Grave State: Rakshan Bani-Etemad’s Mainline,” in Iranian Cinema in a Global Context: Policy, Politics, and Form, ed. Peter Decherney and Blake Atwood (New York: Routledge, 2015), 98.

Figure 4: Still from Mainline (Khūn’bāzī), directed by Rakhshān Banī-I‘timād, 2006.

Mihrjūyī’s Santūrī was another film set among the middle classes that focused on the addiction of one specific individual. It depicts the destruction of a love-match marriage caused by the addiction struggles of the lead male, professional musician ‘Alī Santūrī. The film only screened once in Iran, to foreign guests at the Fajr International Film Festival. Ostensibly the film had screening permit problems because Mihrjūyī used a Kurdish musician who did not have broadcasting permission as the playback singer for lead actor Bahrām Rādān. As I have argued elsewhere, I believe that the feisty and alluring character played by Gulshīftah Farahānī and the portrayal of the intense relationship between the two leads, who embody the antithesis of Islamic virtue, contributed to the banning.17Anne Démy-Geroe. Iranian National Cinema: The Interaction of Policy, Genre, Funding, and Reception. (Abingdon Oxon: Routledge, 2020), 60-62.

Although social issues films were initially intended to deal with the poor in accordance with Iranian Islamic theology, these two films were early examples of an emerging trend of films that I have described elsewhere as the middle class family drama.18Anne Démy-Geroe. Iranian National Cinema: The Interaction of Policy, Genre, Funding, and Reception. (Abingdon Oxon: Routledge, 2020), 67. What remained constant in films portraying drug addiction until 2018 was the depiction of individual addicts from the middle classes, suggesting they were isolated cases rather than a widespread societal problem. This isolation is emphasised through filmic language. In Mainline as Langford noted, “The rather confronting use of extreme close-ups of Kowsari helps to deeply connect the viewer with [the heroin-addicted young woman] Sara’s suffering and with her mother’s desperate attempts to protect her from society and herself.”19Michelle Langford, “Iranian Cinema Looks Inward: The 25th Fajr International Film Festival,” Senses of Cinema 44, 2007. https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2007/festival-reports/fajr-iff-2007/. Several years later Banī-I‘timād’s film Tales (Qissah’hā, 2014) develops the stories of her protagonists from Mainline and other earlier films. Sara has gone clean (although she is emotionally damaged) because her middle-class mother could afford to take her to rehab. In Ice Age, discussed further on, there are numerous medium shots of the female lead smoking alone. ‘Alī Santūrī is despatched to a sanatorium, where he wanders alone as the only drug addict among the mentally unstable.

Figure 5: Still from Santūrī, directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī, 2007.

Mahmūd Ahmadīnizhād’s second presidential term (2009-2013) witnessed unprecedented conflict between the regime and the filmmakers. While the government placed an emphasis on re-harnessing the film industry to its own goals, many social issues filmmakers, by contrast, created controversial films with thinly veiled references to regime corruption and dubious moral practices. Some examples include Private Life (Zindagī-i Khusūsī; dir. Muhammad Husayn Farah’bakhsh, 2012), The Guidance Patrol (Gasht-i Irshād; dir. Sa‘īd Suhaylī, 2012) and Manuscripts Don’t Burn (Dast’nivishtah’hā ni’mīsūzand; dir. Muhammad Rasūluf, 2013). Government aggression was so extreme that on his election Ahmadīnizhād’s moderate successor, Hasan Rūhānī, made a public apology to the filmmakers heralding another relaxation and a surge in independent filmmaking.

Ice Age follows the established model for representing drug addiction as isolated and situated among the middle class. But the content of the film is far from what was previously acceptable. A couple married for ten years suddenly faces a marriage crisis. The husband tries to counter their financial difficulties by working longer hours. His bored wife engages in an affair, attending an unceasing round of parties with her new lover’s circle, resulting in her addiction. The moral ending of the film sees her reach rock bottom, coming to the realisation that she has ruined her life. A commercial melodrama with luxury cars and a stellar cast, including Bahrām Rādān, the film received 6 nominations, one for the Audience Award, and two wins at Fajr that year. It was acceptable to show that failing to adhere to Islamic values can have devastating consequences. What once was forbidden was now permissible, as Javād Shamaqdarī, the Deputy Minister for Cinematographic Affairs, explained to me in an interview in 2013 when he was asked to define “Muslim filmmaking”. This interview took place very late in the Ahmadīnizhād presidency. Statistics showed that the volume of drugs brought into Iran between 2012 and 2015 had increased by 24%.20“Iran: Drug Law Amended to Restrict Use of Capital Punishment,” Global Legal Monitor Library of Congress, August 31, 2017. https://www.loc.gov/item/global-legal-monitor/2017-08-31/iran-drug-law-amended-to-restrict-use-of-capital-punishment/. Kiyā’ī portrayed another element in Ice Agethat ostensibly made people susceptible to drug addiction. He referenced the contemporary financial crisis facing Iranians. Sanctions placed on Iran since 2012, along with government mismanagement resulted in soaring inflation rates – 36.6% for 2013, dropping to 12.08 for 2015, but climbing to a staggering 39.91 by 2019. This significantly impacted the middle classes.21“Iran Inflation Rate 1960-2025,” Macrotrends, accessed October 1, 2025, https://www.macrotrends.net/global-metrics/countries/irn/iran/inflation-rate-cpi.

Figure 6: Still from Ice Age (‘Asr-i Yakhbandān), directed by Mustafā Kiyā’ī, 2015.

Drugs and the Crime Genre

In 2015 an article from the Tehran bureau of The Guardian newspaper about that year’s Fajr International Film Festival entitled “Cars, drugs and virginity tests dominate Iranian film festival” was subtitled, “Tehran’s Fajr film festival … has ditched weighty themes in favour of populist blockbusters.”22“Cars, drugs and virginity tests dominate Iranian film festival,” The Guardian, February 19, 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/world/iran-blog/2015/feb/19/iran-faji-film-festival-blockbusters-dominate. This was a transitional year for films with the relaxation of the regulations under Rouhani evident; drugs and corruption along with violence and crime had become more acceptable to the MCIG. The films selected for the festival were overall more commercial, as the Guardian article makes clear, but some themes were certainly of major sociopolitical relevance. Two films dealing with drugs screened, one of which was Ice Age, discussed above, a film following the narrative structure already established for the representation of drugs, but daring in its content. The second film, a thriller, from Hūman Sayyidī, was at the forefront of a new trend in representation. An advance publicity article for the 2015 Fajr International Film Festival discussedSayyidī’s Confessions of My Dangerous Mind (I‘tirāfāt-i Zihn-i Khatarnāk-i Man, 2015), and noted, “A bit of action and random violence is what sets this movie apart – a characteristic not very common in mainstream Iranian cinema.”23“A Glance at Fajr Festival Must-See Films,” The Financial Tribune, January 30, 2015. https://financialtribune.com/articles/art-and-culture/10106/a-glance-at-fajr-festival-must-see-films. However Sayyidī employed what is a cliché trope in Iranian cinema used to bypass censorship– amnesia. The protagonist wakes up in a random wheatfield and conveniently cannot remember whether he is a drug addict or has cancer. He embarks on a game foisted on him to try to discover the truth, yet another not uncommon device for avoiding censorship. This film received five nominations and one win at Fajr that same year.

Figure 7: Still from Confessions of My Dangerous Mind (I‘tirāfāt-i Zihn-i Khatarnāk-i Man), directed by Hūman Sayyidī, 2015.

Drugs, the Crime Genre and the Working class

The next shift in the representation of drug issues occurred with Sayyidī’s Sheeple (2018) and what is almost a companion piece made a year later, Just 6.5 (2019), the sophomore feature from Sa‘īd Rūstāyī. They have more in common than the theme of drugs and the lead actor Navīd Muhammadzādah, who gives sensational and strikingly different performances in both films.

Sheeple, as most of Sayyidī’s earlier films, is a crime film, but this one is also heavily inflected with social issues, dealing with family values, shame, disloyalty, tradition and child slave labour. It examines the dynamics of the conservative working-class family of a small-time druglord, Shakūr (Farhād Aslānī), who runs a ramshackle crystal meth kitchen for neighbourhood distribution. Shakūr lives with his parents and siblings, each of whom has their own story. The protagonist is his inept but verbose younger brother Shāhīn, who has delusions, fed by his best friend, of taking over the family business. He becomes conflicted when he discovers that the real money is not in the production of ice but in an even more dubious business involving child slave labour. Its strong streak of humanism cements it as Iranian.

Figure 8: Still from Sheeple (Maqz’ẖā-yi kūchak-i zang’zadah), directed by Hūman Sayyidī, 2018.

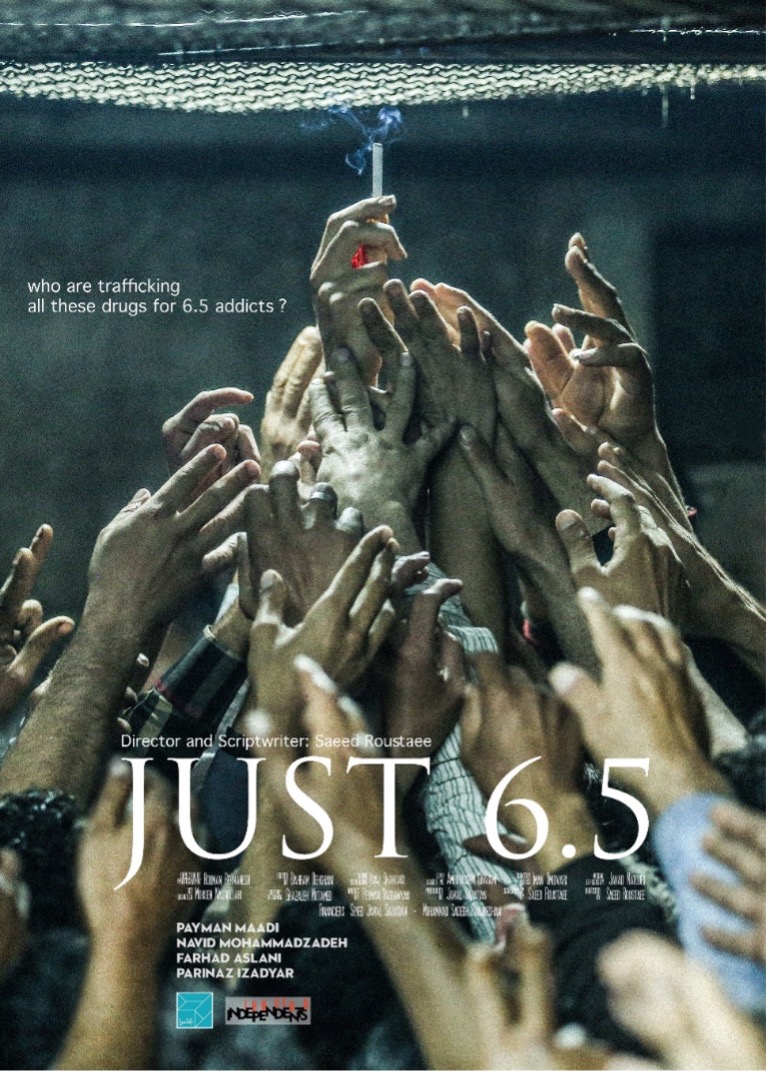

Just 6.5 (aka The Law of Tehran) premiered at the 37th Fajr International Film Festival. It fared well domestically, both critically and commercially, then travelled with considerable international success.24Anne Démy-Geroe, “Just 6.5: A new modulation on the social issues film” in IB Tauris Handboook of Iranian Cinema ed. Michelle Langford, Maryam Ghorbankarimi and Zahra Khosroshahi (London, Bloomsbury, 2025), 163-182. Its major thematic ingredients are class conflict, patriarchy and moral ambiguity alongside drugs. The title refers to the 6.5 million drug users in Iran, reinforcing the film’s fusing of a humanistic message with “the razor’s edge of spiralling tension.”25Deborah Young, “Film Review: Just 6.5 (‘Metri Shesh-o Nim’),” Hollywood Reporter, April 29, 2019. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-reviews/just-65-1205431/

Rūstāyī’s and Sayyidī’s filmic responses were contributions to the contemporaneous public debate around amendments to the drug-trafficking laws. On August 13, 2017, Majlis approved a bill to curtail the application of the death sentence to minor offenders. Just 6.5 first screened in January 2019, less than 18 months later. An important element in the debate was voiced by a member of the Majlis Judicial and Legal Commission who acknowledged that most drug dealers “are not the actual smugglers or ringleaders but are dragged and/or tempted into the crime due to poverty, joblessness and hopelessness … Poverty pushes people to do anything to provide for their families. But our laws did not take this into consideration….” 26“Majlis Endorses Bill to Restrict Death Penalty for Drug Crimes,” The Financial Tribune. August 14, 2017. https://financialtribune.com/articles/people/70331/majlis-endorses-bill-to-restrict-death-penalty-for-drug-crimes. This statement makes the link between drugs, poverty and the worsening economic situation in Iran. These two films, Sheeple and Just 6.5, emphasized working class sentiments.

Figure 9: Still from Sheeple (Maqz’ẖā-yi kūchak-i zang’zadah), directed by Hūman Sayyidī, 2018.

More Than “Just” Genre Films

Both Sheeple and Just 6.5 had international critics scrambling to classify them. While some international critics started to compare the films with the work of directors such as Quentin Tarantino, Guy Ritchie and Anurag Kashyap, suggesting violence, crime, thugs and moral ambiguity, there was another view. Chief film critic for Variety magazine Owen Gleiberman, and Bijan Tehrani, expatriate Iranian writer, film critic and film director, were both confused as to how to classify the films. Tehrani, who had been following Sayyidī closely since Africa (Āfrīqā, 2010), acknowledged the influence of Tarantino on Sheeple but claimed “Houman takes a big step forward and comes up with an extraordinary and shocking film which provides great proof of the birth of a new voice for world cinema.”27Bijani Tehrani, “Sheeple – Birth of a new voice for world cinema,” Cinema Without Borders. May 5, 2019. https://www.cinemawithoutborders.com/sheeple-maghz-haye-kuchak-zang-zadeh/. Gleiberman saw Sheeple as outside the norm: “The cinema of Iran has often been marked by stylistic qualities of delicacy and restraint. It has found ways to speak loudly with a whisper. But … the traumatically explosive… Sheepleamounts to a rather spectacular counterexample.” But he did not position it as derivative of Tarantino or Ritchie. He continued, “Hooman Seyyedi’s Sheeple, “for all its helter-skelter crime-film energy, [is] a serious and humane movie,” (author’s emphasis) and concluded that, “it’s tantamount to a kind of moral myopia to regard [Sheeple] as a genre film.”28Owen Gleiberman, “Film Review: ‘Sheeple’,” Variety, January 15, 2019, https://variety.com/2019/film/reviews/sheeple-review-iranian-film-festival-new-york-1203107426/. Again, this time in a crime-family drama about a family drug business, as with Just 6.5, there is the use of the adjective “humane”, an adjective more usually associated with the social issues films.

Just 6.5 pushes the genre boundary one step further than Sheeple. Rather than focus on the problems depicted in earlier films – a few isolated individual middle class addicts, or the phenomenon of the local neighbourhood drug ring based around a single working class family and arguably posited as something perhaps unusual in Sheeple – Rūstāyī portrays the existence of a widespread social issue and makes a thorough systemic analysis down to the children of both protagonists. Deborah Young, a senior critic highly respected in Iran for her knowledgeable and insightful criticism of Iranian cinema, expresses ideas about Just 6.5 similar to Gleiberman’s for Sheeple. “This differs from its genre companions in angrily underlining the human damage caused by the abuse of heroin, cocaine and crack.”29Deborah Young, “Just 6. 5 (‘Metri Shesh-o Nim’): Film Review,” Hollywood Reporter, April 29, 2019. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-reviews/just-65-1205431/. Humanism is a characteristic that has often and long been attributed to post-revolutionary Iranian cinema by a range of people from Iranian film bureaucrats, politicians and critics to Western academics.30For examples see Anne Démy-Geroe, Iranian National Cinema: The Interaction of Policy, Genre, Funding, and Reception (Abingdon Oxon: Routledge, 2020), 98-99. Here the humanistic lens on the issue of drugs, hybridised with the action genre, again suggests the social issues genre, while eschewing another of its common characteristics, melodrama. At the same time, the convention of the thriller in this film downplays suspense as a less important element. Instead, the emphasis is on an emotional critique of a system unable to solve social problems. A new and prominent element added to the representation of drug addiction in both Sheeple and Just 6.5, along with the class depiction, was the execution of the druglord. Furthermore, the danger of the work for the narcotics agents is highlighted in Just 6.5. Rūstāyī confirmed his intent with Just 6.5 in an interview for the French release of the film. When asked if he had intended from the beginning for his film to be a thriller, as the French press has categorised it, he replied:

Not quite. Let’s say that the social issue got the upper hand in my mind. And that I arrived at the thriller as a consequence, quite simply because the problem that I raise affects circles – the poor, the Mafiosi, the police, the justice system – which are involved in the genre.31Jaques Mandelbaum, “Saeed Roustayi: ‘Un cinéaste iranien doit être persévérant’,” Le Monde, July 26 2021. https://www.lemonde.fr/culture/article/2021/07/26/saeed-roustayi-un-cineaste-iranien-doit-etre-perseverant_6089600_3246.html [translated by the author]. This is further confirmed by Rūstāyī’s unarguable use of the social issues genre in both his subsequent films, Leila’s Brothers (Barādarān-i Laylā, 2022) and Woman and Child (Zan u Bachchah, 2025).

Figure 10: Poster for the film Just 6.5 (Mitrī shīsh u nīm), directed by Sa‘īd Rūstāyī, 2019.

It is worth describing an early scene in Just 6.5 – the beautifully executed police round-up of every homeless person and drug user in South Tehran, where drugs, poverty and overcrowding are rife. This lengthy scene starts with close-ups and medium shots of many individuals, even a group shot of women using drugs, the camera pulling back to show their environment, the cluster of large concrete pipes in which they live. When the police arrive panic sets in. But the space empties quickly and the camera lingers on the deserted space, rather than following the mechanics of arresting and transporting the huge groups of addicts to the lockup. The sequence has worked to show the people, their environment, and the scope of the problem. Back at the lockup, this is reinforced as the shots of individuals become those of groups: slow pans of shirtless male bodies, tightly packed, tightly framed. Many are clearly in a narcotized state, their swaying bodies fragile and emaciated. The camera zeroes in, to close-ups of groups of faces. Four of the youths will not remove their shirts, finally revealing to the frustrated officer that they are actually women. A high angle shot of a bedraggled group of women making their way through the crowd and up a staircase follows. It is very clear that Rūstāyī utilised the typical Iranian neorealist device of using non-professionals in documentary-like footage. There is no denying the magnitude of the drug problem or the poverty. The intimate portraits of the groups of emaciated bodies connect the film visually to the lepers of Furūgh Farrukhzād’s The House Is Black (Khānah Siyāh Ast, 1963), a film often cited by Iranian directors.

Figure 11: In the lockup after the roundup. It’s clear that non-professionals were used. Still from Just 6.5 (Mitrī shīsh u nīm), directed by Sa‘īd Rūstāyī, 2019. Courtesy of Muhammad Atibbā’ī, Iranian Independents.

As Rūstāyī has explained, he was not seeking to make a crime thriller. Content dictated the final form as he sought to highlight Iran’s massive drug problem and its sources, building a film that divides sympathy and understanding between the narcotics agent and the druglord, both victims of the system. The ending hauntingly echoes a statement made by the previously quoted Jalīl Rahīmī Jahān’ābādī, member of the Majlis Judicial and Legal Commission: “Four decades of war on drugs has yielded very little. Our laws clearly failed to have the desired deterrence effect. There is a need for an overhaul ….”32“Majlis Endorses Bill to Restrict Death Penalty for Drug Crimes,” The Financial Tribune, August 14, 2017. https://financialtribune.com/articles/people/70331/majlis-endorses-bill-to-restrict-death-penalty-for-drug-crimes. The worsening economic conditions in Iran, to which he was referring in August 2017, led to an almost continuous series of nationwide strikes and protests. In 2018, a range of strikes occurred, from miners and truckers to conservative bazaris. In 2019 the protest known as Bloody November (or Bloody Ābān), in response to a 50-200% increase in fuel prices, spread quickly, embracing a wide range of social groups and classes, including Tehrani bus and taxi drivers who organised protests in January 2020. In all, the protests continued for around a year. In September 2022 protests recurred. The catalyst was the death-in-custody of Mahsā Amīnī. The protests transformed into the ongoing Woman Life Freedom movement. Government repression was harsh; aside from internet cuts there was shocking violence with many deaths.

By the conclusion of the film, Rūstāyī’s protagonist, the narcotics agent, has traversed a trajectory from what seems to be a mix of idealism and careerism to complete disillusionment as he finally rounds up the major drug lord who has eluded him for years. He realises the full impact of the drug problem, and what he personally has sacrificed by being involved in attempting to control it. Moreover, he understands that the current approach to solving the problem will never be successful. He rejects a promotion and leaves the force. Sadly, this vital scene was removed for domestic release. Without it the film changes from a probing analysis of the problem – a successful drug raid with what, for the narcotics agent, should be a satisfying conclusion of the capture and execution of the druglord to a simple police procedural.

The drug laws implemented in 2017 led to an almost immediate and dramatic decrease in executions between 2018 and 2020. But this was short-lived. In 2021 two new figures entered the scene – a new president, Ibrāhīm Ra’īsī, and a new Head of the Judiciary, Ghulām Husayn Izhah’ī – with a significant swing in the anti-narcotics policy. Amnesty International claims to have analysed official statements that criticized the 2017 reforms and called for increased use of the death penalty. There has been a horrifying upward trajectory since 2021, with 481 drug-related executions in 2023—an 89% increase from 2022 and a 264% increase from 2021, when 132 people were executed for drug-related offenses.33“Iran executes 853 people in eight-year high amid relentless repression and renewed ‘war on drugs’,” Amnesty International News, April 4, 2024. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2024/04/iran-executes-853-people-in-eight-year-high-amid-relentless-repression-and-renewed-war-on-drugs/.

Woman, Life, Freedom and film

Concurrently, the inflation rate continued to rise, as discussed earlier. In 2022, with the shocking death of Mahsā Amīnī, protests erupted worldwide, alongside the rise of the Woman, Life, Freedom movement. Filmmakers were quick to represent the contemporary situation onscreen. Filmmaking in Iran shifted seismically with general rebellion in, for example, the portrayal of veiling, reflecting the changes on the streets. Filmmakers broadened their focus from drugs to other wide-ranging problems.

In 2024 veteran filmmaker Muhammad Rasūluf made The Seed of the Sacred Fig (Dānah-yi anjīr-i ma‘ābid) which follows the family of a man who has been promoted to state investigator. The limitations on the family’s freedom increase exponentially and although at huge personal costs to each family member there will be rewards such as an apartment large enough for each daughter to have her own bedroom! Drug representation is not present, but the abandoning of a basic tenet of Iranian filmmaking, the use of allegory, makes it useful to discuss. The film begins traditionally, but at the two-thirds point, Rasūluf, who had made sophisticated allegorical films such as The White Meadows (Kishtzār’hā-yi sipīd, 2009), turns to horror and thriller possibly comparable to Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining(1980). When interviewed about this he explained that he now felt that allegory was a cowardly type of self-censorship.34“Mohammad Rasoulof in conversation [conducted by the author],” ACMI, October 24, 2024. https://www.acmi.net.au/whats-on/mohammad-rasoulof-in-cinemas/mohammad-rasoulof-in-conversation/.

Figure 12: Still from Critical Zone (Mantaqah-yi buhrānī), directed by ‘Alī Ahmadzādah, 2023.

Young independent filmmakers took up the mantle very quickly, defying all government rules with a string of independent films of varying quality. One of these which did achieve traction was Critical Zone (Mantaqah-yi buhrānī, 2023), ‘Alī Ahmadzādah’s third feature, which won the Golden Leopard in Locarno in 2023. All three of Ahmadzādah’s films to date have been road movies, featuring wild parties and drugs. The earlier films, such as Kami’s Party (Mihmūnī-i Kāmī, 2013), portray the lifestyle of wealthy young Iranians and can perhaps be claimed as non-didactic social issues films. Critical Zone follows the protagonist, a pusher, one night as he prepares packages of drugs then drives around Tehran making deliveries. As with his earlier films, Critical Zone does not judge its characters, rather it tries to portray the contemporary atmosphere, showing a wild desperation in scenes of young people and their encounters with the law.

Conclusion

Drug addiction has been recognised as a major social issue by both Iranian society and the clergy for more than forty years, yet despite efforts little has been achieved to combat it. Its depiction has been a popular topic for independent filmmakers and while “insider” films on the subject are often formulaic in their use of cliché plot lines and melodrama, independent filmmakers, some discussed here, from Mainline and Santūrī to Just 6.5 and Critical Zone, have experimented in hybridising the topic with others, introducing new elements, taking risks in pushing the boundaries of the acceptable, and respecting their audiences with scripts of integrity. The humanism expected of Iranian cinema is present to varying degrees in all of them. Some of the filmmakers were careful in their approach, others could never have anticipated domestic or even international screening permission.35The government requires a separate permit for both domestic and international screenings, with films receiving both, neither, just domestic or just international. This, in itself, is a fascinating topic. Nonetheless they have attracted star talent from Bahrām Rādān to Bārān Kawsarī, Navīd Muhammadzādah, and Paymān Ma‘ādī, to create works which have stood the test of time.

Cite this article

A major change in Iranian cinema under Muhammad Khātamī’s Reformist presidency was the rise of social issue films as a kind of genre. There was also a liberalisation of the cinema regulations. Illegal drug use and addiction have long been one of Iran’s most pressing social problems and it was not surprising that they would form a major theme in social issues films. This article will trace a brief history of their changing representation from 2000 to 2025 within their social and political context.