Through the Olive Trees: Probing the Premise of ‘Reel’ Narrative in an Eco-poetic Film

Figure 1: Poster for the film Through the Olive Trees (Zīr-i Dirakhtān-i Zaytūn), directed by ʿAbbās Kiyārustamī, 1994.

Through the Olive Trees (Zīr-i Dirakhtān-i Zaytūn, ʿAbbās Kiyārustamī, 1994)1The title of the film is shortened to Olive Trees henceforth. is the third and last installment of ʿAbbās Kiyārustamī’s Koker trilogy filmed in the village of Koker, in the township of Rustam Ābād in northern Iran.2The previous films of the trilogy are: Where Is the Friend’s House? (Khānah-yi Dūst Kujāst? 1987) and Life, and Nothing More (Zindagī va Dīgar Hīch, 1992). Olive Trees is a seemingly simple story of rural life as though Kiyārustamī is showing the spectators another episode of reality in the same village where he filmed his previous movies. However, as the film continues, the audience comes to understand that there is nothing simple or even real about this story at all. In Olive Trees, Kiyārustamī questions the authenticity of cinematic stories, including his own. More vehemently than in the director’s previous films, Olive Trees portrays a multi-layered, paradoxical, and ironic meta-cinematic narrative that questions the reality of the “reel” world and the role of the filmmaker in creating such “reality”. When Kiyārustamī made the third installation of the Koker trilogy, he was already celebrated in global film circuits as an auteur who excels in the art of improvisation by recruiting amateur actors to play themselves. He was taken as a filmmaker who produces “authentic” neorealist films about rural life in Iran. With this context in mind, Olive Trees was made to playfully and ironically question the premise of authenticity of ‘Kiyārustamī style’ reality. The ensuing discussion explores this topic in both the formal and contextual levels in the film.

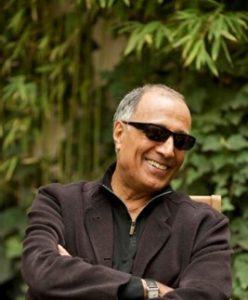

ʿAbbās Kiyārustamī (1940-2016), was one of the most prolific Iranian directors and arguably the most acclaimed Iranian filmmaker outside of Iran. He was praised throughout his career by distinguished international directors such as Jean Luc Godard and Akira Kurosawa.3Jean Luc Godard said: “Film begins with DW Griffith and ends with Abbas Kiarostami.” Quoted in “Abbas Kiarostami/Movies,” Guardian, April 28, 2005, accessed July 2, 2024 https://www.theguardian.com/film/2005/apr/28/hayfilmfestival2005.guardianhayfestival

Praising Kiyārustamī’s aesthetics, Akira Kurosawa told him: “What I like about your films is their simplicity and narrative fluency. It is hard to describe them. One has to see them.” See Shohreh Golparian, “The Emperor and I: Abbas Kiarostami Meets Akira Kurosawa,” Film International Magazine 1, no. 4 (Autumn 1993): 4-7. It was the Koker trilogy that introduced Kiyārustamī, and by extension post-revolutionary Iranian cinema, to film festivals and cinephiles around the world. Olive Trees secured multiple awards and was praised by critics for its artistic and aesthetic merits, especially in France. The most notable among the accolades for the film were its nomination for Palm D’Or at the 1994 Cannes Film Festival and the winning of the Silver Hugo Award at the Chicago Film Festival in the same year. The critical success of Olive Trees paved the way for Kiyārustamī’s eventual winning of Palm D’Or at Cannes Film Festival three years later for Taste of Cherry (Taʿm-i Gīlās, 1997).

Figure 2: Portrait of ʿAbbās Kiyārustamī

Narrative

Kiyārustamī was inspired to make Olive Trees while he was producing Life, and Nothing More (Zindagī va Dīgar Hīch, 1992) in Koker. He fancied to make a movie about the continuity of life and love with the backdrop of a quake-struck displaced community that had lost more than 45,000 of its inhabitants. Paradoxically, given this grim context, he chose to focus on life rather than death, and to meditate on hope, love, and nature from within this disastrous moment in Iran’s history. It is important to indicate that the deadly earthquake in the Rūdbār area opened unhealed wounds for the nation. Iranians in early 1990s were still traumatized by the aftermath of mass imprisonments of the opposing groups and mass executions of 1980s,4Iran Tribunal recorded 11,000 executions in the 1980s by the Islamic regime “but an alternative estimation suggests that the number exceeded 20,000.” See “History of Mass Executions in 1980s,” Iran Tribunal, accessed July 10, 2024, https://irantribunal.com/mass-executions/history-of-mass-executions-in-1980s/. as well as the remnants of Iran-Iraq war that lasted eight years and caused around 1,000,000 causalities, as well as bringing economic hardship to the nation.

The story of Olive Trees does not contemplate on the sociopolitical issues that captivated Iranians at the time. Instead, (in the middle layer of the narrative, which is presented as the “reality” outside of the cinematic story) it is a seemingly simple tale of a young man’s (Husayn, played by Husayn Rizā’ī) love for a woman (Tāhirah, played by Tāhirah Lādaniyān). Husayn, who was previously working as a mason, is pictured in the film in his second attempt to win Tāhirah’s heart, after being rejected once before. Tāhirah has lost all her family members in the earthquake and is left only with her grandmother. Before the earthquake, Tāhirah’s family found an illiterate man’s proposal to their daughter insulting. Her grandmother also believes that Husayn’s social status is below that of her grandchild, an aspiring student. Husayn’s logic to win Tāhirah’s heart follows the idea that since life is fleeting, being illiterate or not having money should not become a barrier to love. While this plotline is unraveling, the film also depicts Husayn and Tāhirah being picked by a fictional film crew to play a newlywed couple. To the fictional filmmaker’s dismay, Tāhirah is unable to differentiate between off-camera reality and on-camera acting. Hence, she refuses to talk to Husayn on-set and does not deliver her lines properly. It causes frustration for the (fictional) crew and creates a comedy for the viewers.

The Sketch of the three layers of Through the Olive Trees

|

The first layer: a fictional film crew are making a film. The process of filmmaking by a fictional director played by Muhammad ‛Alī Kishāvarz is shown. |

||

|

The second layer: the ‘real’ life of the village, as people are depicted in their ‘everyday’ activities. Husayn and Tāhirah as their ‘real’ selves are depicted. |

||

|

The third layer: performance of Tāhirah and Husayn as actors in Kishāvarz’s movie. In this layer Tāhirah and Husayn are a married couple |

||

As the above chart outlines, there are at least three layers of narrative in Olive Trees. One layer is the process of making a film by a fictional film crew. The second layer is the story of everyday life in the village, their community life, and behind-the-scenes interactions with the cast. The third layer shows on-camera moments with Husayn and Tāhirah, unsuccessfully playing the same sequence repeatedly, in the hopes that Tāhirah would finally talk to Husayn in a less rigid more natural manner.5Previous sequences were equally humorous, showing how Hussein (the film crew errand boy) ended up replacing another fellow villager as Tāhirah’s fictional partner. The previous man was stuttering in front of young women, hence was released by the film director. The viewer understands, of course, that both the so-called off-camera reality and on-camera acting are fictional. The real and fictional layers of the film are scripted, set up and played by (mostly) amateur actors. The story’s meta-narrative layout showcases stories within the frame story that unfold in a nonlinear manner. The on-camera details interfere with off-camera stories to the point that the viewer cannot comprehend a complete, uninterrupted fictive story, as is shown in a more conventional film.

Figure 3: Husayn and Tāhirah, the film’s main characters, stand apart on a porch that visually reflects the emotional and societal distance between them. A still from the film Through the Olive Trees (Zīr-i Dirakhtān-i Zaytūn), directed by ʿAbbās Kiyārustamī, 1994. accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iAe8_O_4VZI (01:08:42).

Olive Trees has a meta-cinematic structure as well, since the film (a cinematic production) shows the making of a film (an embedded fictive cinematic production) to draw the viewers’ attention to the artificiality of on-screen “reality.” As mentioned before, in the opening sequences, Olive Trees appears deceptively simple. But once the spectators continue watching, they realize that the multilayered and meta-cinematic structure of the film is quite sophisticated and self-reflexive. Kiyārustamī playfully intermingles the assumed “diegetic” and “non-diegetic” stories to show his mastery in making a multi-narrative poetic realist film.

Olive Trees unfolds in a non-linear, multilayered meta-narrative style to depict the yearning for a beloved and dealing with the loss of loved ones in a half-destroyed village. Kiyārustamī pictures a devastated community yet beaming with love and life. The hustle and bustle of the village, the blooming of flowers, and the glamour of trees minimize the impact of the natural disaster. Loss and love are juxtaposed to remind the viewer that life offers paradoxical paradigms simultaneously. The story within story structure of the film, known in literary studies as the “Chinese Box Structure,” or “Framed Narrative Structure” is a well-known narrative format for Iranian audiences. It is rehearsed in such classical works as Thousand and One Nights, Rumi’s Masnavī and Kalīlah and Dimnah. The narrative structure is also spatial and circular, which is closer to Persian poetry (such as ghazal poetry of Rumi and Hāfiz).6The affinities between Kiyārustamī’s aesthetics in Koker trilogy and the spatial format of Ghazal poetry is diligently explored in Khatereh Sheibani, The Poetics of Iranian Cinema: Aesthetics, Modernity and Film after the Revolution (London: I.B. Tauris, 2011).

On a philosophical level, Kiyārustamī reminds us that life is not a linear journey as often simplified in many commercial movies. It is rather non-linear and multilayered. Olive Trees maintains a narrative style that exposes the artificiality of what is seen in mainstream cinema. The meta-cinematic structure of the movie contains the three layers of stories intertwined into one another. The whole film remains an unfinished story showcased in fragmented sequences. The director, Kiyārustamī, evades “seamless classical editing” that would have offered a linear story. Instead, the film narrative and its editing are “disjunctive” and open-ended, which recall the structure of both Persian stories such as Thousand and One Nights as well as the format of ghazals by Hāfiz.

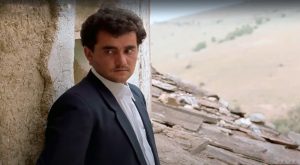

The notion of love, which is a central theme in Persian literature (such as the ghazals of Hāfiz and Rumi) is also a predominant subject in Olive Trees. After making Report (Guzārish, 1977), Kiyārustamī shows a comeback to romantic stories in Olive Trees. Although both films have melodramatic elements, in none of them love is glamorized. Instead, we see a pessimistic twist and (in this film) a humorous depiction of love. The sarcastic point of view, the unheroic and even waggish characterization of the lover, and the representation of a non-reciprocal love makes it hard to consider the film as a love story in a traditional sense. Husayn does not look as handsome, masculine or assertive as the archetypal image of lovers such as Khusraw in Nizāmī’s Khusraw and Shīrīn or in movies such as Qārūn’s Treasure (‛Alī played by Muhammad ‛Alī Fardīn) (Ganj-i Qārūn, Siyāmak Yāsimī, 1965). The romance in Olive Trees is reduced to a comic situation that may or may not turn to a serious love affair. Romance in Olive Trees has distancing effect; therefore, the audience does not identify with the lover and may not commiserate with his feelings. That said, while the portrayal of Husayn does not necessarily recall the perfect lover, his determination and diligence are admirable. Through the characterization of Husayn, the director gave precedence to human agency and perseverance without idealizing romance.

Figure 4: The character Husayn in the film Through the Olive Trees (Zīr-i Dirakhtān-i Zaytūn), directed by ʿAbbās Kiyārustamī, 1994.

The characterization of Husayn is far from the ideal character of traditional heroes, yet his words to Tāhirah about the ephemeral nature of life and the importance of seizing the present moment, being happy with what we have are worth pondering upon. Unconventionally, the director decided to have an illiterate uncharismatic character delivering the lines that are normally reserved for charismatic and wise characters. The filmgoers’ expectations on many levels, including the narrative style and characterization are deconstructed by Kiyārustamī.

Nonetheless, the film concentrates on the power of life, which surmounts tragedy and death. It is the pursuit of happiness, love, and the desire to live that conveys meaning to the lives of people in mourning. Olive Trees shows that hope and perseverance outlived the earthquake, as do the trees themselves. Olive trees become an emblem of fortitude and endurance. Their predominant presence in the filming location inspired the director’s choice in naming the film. The olive grove, with its prevalent visual and thematic signification in the film could, even be considered the main character. The subject of love is juxtaposed with the significance of nature as represented by the trees in the film. Hence, love, passion, perseverance and having dreams for a better life are the most valued concepts in this eco-poetic film.

Figure 5: The theme of love is juxtaposed with the significance of nature, represented by the trees. A still from the film Through the Olive Trees (Zīr-i Dirakhtān-i Zaytūn), directed by ʿAbbās Kiyārustamī, 1994. accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iAe8_O_4VZI (01:34:34).

A multilayered narrative in a nonlinear fashion, and a meta-cinematic arrangement provide the film with a complex structure which demands the audience’s participation in constructing meaning while watching the film. In this way, the audience is challenged to play a semiological game as a seemingly simple story becomes a complicated one.

Perfecting the Genre of ‘Rural Movies’ in Through the Olive Trees

With the Iranian revolution of 1979, a politicized and fundamentalist interpretation of Islam became the dominant narrative propagated by the new regime, prescribing behavior in all levels of social life. The mandatory hijab for women became an emblem of the Islamic government and a message of defiance to the West. Naturally, the Iranian film industry, as with other social sectors, was affected by such ideological mandates. Filmmakers faced new limitations in depicting everyday life, especially when they wanted to zoom their camera in private spaces. It is noteworthy that the newly appointed Islamists in power exerted more control over urban spaces compared to rural and nomadic areas. The image of an Islamic Iran was mostly showcased in films and television programs that were produced to depict an urban Iran. With hijabized women pictured even in the intimacy of their bedroom and fictional couples who could not even touch each other’s hands, making realist films about urban life became next to impossible. The time for making fascinating realist melodramas such as Report was over.

Beyond the Islamic mandates in gender behavior and sexual politics, the revolution and war created profound sociopolitical transformations. As a result, the Iranian film industry experienced fundamental amendments. The existing cinematic genres and modes had to be modified to ensure the survival of the medium. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, two distinct cinematic genres thrived in Iranian film industry: War Movies and Rural Movies. Popular War Movies such as Ibrāhīm Hātamīkiyā’s From Karkheh to Rein (Az Karkhah tā Rāyn, 1993) were more in line with the regime’s propagandist goals of altruist exertions of soldiers fighting with “the enemy,” Rural Movies, with Kiyārustamī as the genre’s most important representative, mostly evaded ideologically oriented themes of sacrifice, martyrdom, loyalty to one’s country, and religion to instead embrace ontological and existential questions. Refreshingly, Kiyārustamī’s rural films mapped a new artistic route to transcend hope, love and, at times, romance in the absence of ideology. Set within vast farmlands, olive groves, and secluded villages, the characters of Kiyārustamī’s films enjoyed open spaces to ponder deeper questions about life and existence outside of the current political situation. The imagery of slow-paced rural living had a meditative impact on the traumatized Iranian viewers who were constantly experiencing adversity in their daily lives and bombarded with ideological-ridden visual aesthetics.

Figure 6: The rural landscape depicted in Kiyārustamī’s film. A still from the film Through the Olive Trees (Zīr-i Dirakhtān-i Zaytūn), directed by ʿAbbās Kiyārustamī, 1994. accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iAe8_O_4VZI (00:06:34).

With the Koker trilogy,7The village of Koker was introduced to him by a visionary colleague and fellow filmmaker Kāmbūziyā Partuvī. Kiyārustamī, who had already made seven feature films and semi-documentaries about city life, trained his camera to the rural domains. The genre of (art-house) Rural Movies in Iranian cinema was not initiated by Kiyārustamī. It was already rehearsed by notable filmmakers such as Amīr Nādirī and Suhrāb Shahīd-Sālis. Like these directors, Kiyārustamī found a more liberal space in rural settings to practice his poetic realist style. The liberal aura in the post-revolutionary village movies was the result of a less controlled and less politicized environment of villages.

Koker trilogy practiced realism. In Olive Trees, as with the previous films of the trio, the cultural and societal depiction of life in corresponded with a natural rural atmosphere. Unlike films made in cities, the viewers are offered relaxed and realistic human interactions. What is interesting in Olive Trees is that the liberal vibe of the rural space influenced the film grammar. Kiyārustamī freed his film from more conventional stylistic choices such as excessive closeup shots, medium shots, shot/reverse-angle shots for dialogue sequences, as well as ‘seamless classical editing’. Instead, Olive Trees perfected Kiyārustamī’s employment of deep focus, long shots and extreme long shots, long takes, and slow-pace editing. A superb example of a deep focus sequence, which also employed extreme long shots of the subjects, studded with an extreme long take, can be found in the last sequence of the film.8The following example is quoted from Khatereh Sheibani, The Poetics of Iranian Cinema: Aesthetics, Modernity and Film After the Revolution (London: I.B. Tauris, 2011), 62-63.

In a long, static take with deep focus, Husayn is shown following Tāhirah, apparently proposing to her once again. The camera tilts down the hill through the olive trees and into an open field after the fictional crew has finished shooting the film. Here the couple are depicted (deceptively) in their real, off-camera lives. They fade into white dots in the green landscape. As they move further away, the audience no longer hears Husayn’s pleading.

Figure 7: Husayn is shown following Tāhirah, seemingly proposing to her once again. A still from the film Through the Olive Trees (Zīr-i Dirakhtān-i Zaytūn), directed by ʿAbbās Kiyārustamī, 1994. accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iAe8_O_4VZI (01:36:33).

After a fairly long silence, the audience is given the privilege of hearing the soundtrack once again, but disappointingly it is not Tāhirah and Husayn’s conversation. Instead, it is a peaceful piece of classical music: “Concerto for Oboe and Strings” by Domenico Cimarosa. This extremely static long take with deep focus continues as we see Husayn running towards the camera once again. Does he have good news? The audience can only assume so. Here, the depth of focus gives a more realistic, less theatrical image of life with its complex messages. This last shot is a reflection of the actual passage of time and makes the entire movie seem to be one long episode in which the viewer is suspended between film fiction and reality. The deep focus that shows reality as a whole, especially in the absence of a soundtrack, proposes a unique cinematic language, offering ultimate liberation from the constructed meaning imposed through traditional montage images that break down the action into cuts.

Kiyārustamī’s rejection of the classic editing aesthetics gives the audience of Olive Trees maximum freedom to conclude the film either way. The fact that this episode is presented in its seemingly physical entirety makes it ambiguous, if not undecidable. In the last sequence, the audience does not see the actors in close-ups that would reveal their facial expressions accompanied by their voices. The choice of deep focus, which brings uncertainty, is especially important in suggesting that Husayn and Tāhirah are shown in real, off-camera moments – although this is a deceptive twist, and in any case, this is only a film or a fictive imitation of reality. The last sequence could suggest that people’s real personalities are much more complex and intriguing than the characters they play in front of a camera. It displays Kiyārustamī’s perfection of the employment of deep focus in a long take in a natural landscape.

Figure 8: The final sequence of Olive Trees showcases Kiyārustamī’s mastery of deep focus in a long natural take. A still from the film Through the Olive Trees (Zīr-i Dirakhtān-i Zaytūn), directed by ʿAbbās Kiyārustamī, 1994, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iAe8_O_4VZI (01:38:02).

In the post-revolutionary context, Kiyārustamī decided to turn his gaze to rural spaces in the trilogy to evade a non-realistic portrayal of life. He succeeded to side-step the religiosity that was promoted by state-funded films of the 1980s and 1990s. Rural Movies provided a transcendental escape for Iranian filmgoers. They created a much needed peaceful and serene vibe that was almost therapeutic. Instead of pondering on politics and ideology, humanism became the quintessential appeal of the trilogy. Olive Trees sealed a cinematic trilogy that offered an innovative narrative and stylistic approach in Iranian cinema. A new aesthetic vista started shaping in Iranian cinema with Kiyārustamī at its forefront. As indicated above, Rural Movies didn’t start with Kiyārustamī, but his aesthetic choices made his pastoral films the most outstanding examples of the genre. When Kiyārustamī became a canonized filmmaker, his auteuristic choices, including his generic and aesthetic eccentricities became known as the Kiyārustamī School of filmmaking. The Kiyārustamī Film School was later imitated, adopted, and remodified by the next generation of filmmakers in Iran. Ja‛far Panāhī and Bahman Qubādī are among the directors who were initially trained by Kiyārustamī and made their first movies in line with Kiyārustamī aesthetics. Later on, both Panāhī and Qubādī attained their own cinematic language and produced masterpieces on their own accord.

Stylistics

Olive Trees, like almost all Kiyārustamī’s films, is a low-budget, neorealist film that typically employs amateur actors, on-location shooting, and available lighting. The mise-en-scène appears non-staged and authentic. The only professional actor of the film is Muhammad ‛Alī Kishāvarz who plays the role of the fictional director/Kiyārustamī’s alter ego in the film. Superficially, Olive Trees seems to have an undeveloped story line, which comprises of a Tehrani film crew coming to a northern village to film a simple, documentary-like story. The minimalist mise-en-scène with non-professional acting and the on-location setting may suggest that the film was made with no or minimal directorship. As noted, only after the film ends, the viewer realizes that the film has a complex storyline, alluding to profound existential questions about life, love, and death. Olive Trees, followed by Taste of Cherry (1998) and The Wind Will Carry Us (Bād mā rā khvāhad burd, 2000) are among Kiyārustamī’s most philosophical films.

Figure 9: Muhammad ‛Alī Kishāvarz, who plays the role of the fictional director, along with the directing team. A still from the film Through the Olive Trees (Zīr-i Dirakhtān-i Zaytūn), directed by ʿAbbās Kiyārustamī, 1994. accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iAe8_O_4VZI (00:27:04).

What the audience sees in the movie (in every layer of the film) is in fact meticulously planned, scripted, and designed by Kiyārustamī. None of the ‘natural’ or amateur looking dialogues were uttered spontaneously by the actors. They were all scripted by the director. A short documentary film about the making of Olive Trees, consisting of footages of behind-the-scenes sequences, reveals the meticulous supervision and intervention of Kiyārustamī on every aspect of acting, camera movements, cinematography, and mise-en-scène.9Beyond Olive Trees (Ānsū-yi Dirakhtān-i Zaytūn), dir. Ḥamīdah Sharīf-Rād (Iran, 2018, 32 min.) is a documentary that looks behind the scenes of Through Olive Trees. Sharīf-Rād made the documentary based on the footage taken by Bahman Kiyārustamī during the making of the feature film. The documentary reaffirms the fact that there is nothing simple, improvised, or unassuming about this seemingly simple and modest film. Olive Trees was directed, produced, edited by Kiyārustamī. It is a sublime example of auteur cinema in Iran. He had overall artistic and creative control over the production.

A significant feature of Olive Trees is the use of local non-actors and the employment of regional dialects in the film. Because the cast are local Gīlakīs, their dialect and acting rehearse the ethnic veracity of rural life in the Rūdbār region. Even in the setting of a small village such as Koker, we see cultural and linguistic diversity. For instance, the Roma people (known in Iran as the ‘kawlī’) have their own dialect, rituals, and traditions. The villagers consist of diverse communities with economic and cultural differences. The film highlights the ethnic and cultural diversity of Iran, something not seen in most official narratives. The stylistic choice of the director to make a village as the epicentre of the narrative enhances the idea that Iran is more than its capital Tehran and the major cities. Iran is a multi-cultural and multi-linguistic country, yet rural Iran has been always marginalized in Iranian cinema. Even when represented, rural life has often been appropriated through an urbanist point of view. This is even visible in acclaimed films such as The Journey of the Stone (Safar-i Sang, Mas‛ūd Kīmiyā’ī, 1978). In this film, the employment of well-known stars such as Īraj Rād, Farzānah Ta’īdī, Gītī Pāshā’ī, and Ja‛far Vālī who deliver their lines in a theatrical tone and non-specified dialect makes it difficult for film viewers to imagine the well-known stars as authentic rural characters.

|

|

|

Figure 10-11: Use of local non-actors and incorporation of regional dialects. Stills from the film Through the Olive Trees (Zīr-i Dirakhtān-i Zaytūn), directed by ʿAbbās Kiyārustamī, 1994.

The accuracy of the dramatic situation in Olive Trees does not merely rest on the choice of a local cast. The film resists the idea of stereotypical representation of rural people as quintessentially different from their urban counterparts. The fictional film crew in Olive Trees try to impose their own presumptions of village life onto the local cast. In their interactions with the Koker community, the fictional director (Kishāvarz) and his team are constantly challenged by the villagers. Tāhirah in particular defies the film crew and makes them understand the reality of village life with more open-mindedness, not through urbanized cliches. At one point, the fictive director/Kishāvarz and Ms. Shīvā insist that Tāhirah should wear local costumes. Tāhirah initially resists the idea. She tells Ms. Shīvā that only old women, and the illiterate kawlī women wear local costumes. Her normal attire (off-set) is more like the urban schoolgirls uniform in the 1990s: a baggy manteau and a scarf. However, she wanted to appear on camera with a party dress. In her everyday conversations, she does not speak Gīlakī but the standard Persian dialect. Eventually, despite her resistance, she is forced by the film crew to wear the traditional dress and speak with a Gīlakī dialect. Tāhirah, however still manages to defy the director’s authorial power as she does not talk to Husayn on the set.

Overall, since modernity was implemented in Iranian cities, many urbanized Iranians have showcased a sense of superiority over people who live in small towns and villages. Residents of Tehran sometimes use the pejorative term of “Shahristānī” to refer to people who live outside of the capital. The Shahristānīs are normally considered as low class, less cultured, and less educated. The Shahristānīs are assumed to be on the lower level of the hierarchy both culturally and intellectually. The presumed inferiority of the Shahristānīs is challenged and defied by Tāhirah. She teaches the urban film crew a lesson about equality and equity of all Iranians, regardless of their place of residence. The role of director, the authorial power, is questioned in the characterization of Kishāvarz as the director of the film within the film. Kiyārustamī criticizes his alter ego, and by extension questions his own role as the author and director of the film.

Figure 12: Ms. Shīvā urges Tāhirah to wear local costumes, but Tāhirah resists, saying only old and illiterate kawlī women do. A still from the film Through the Olive Trees (Zīr-i Dirakhtān-i Zaytūn), directed by ʿAbbās Kiyārustamī, 1994. accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iAe8_O_4VZI (00:11:24).

Olive Trees shows that the Tehrani crew came to the village with presumptions about their filming subjects. Their expectations, it seems, were unrealistic. They faced difficulty and were corrected and defied by the villagers. They discovered the real village by reflecting on their own mistakes. The fictional director eventually becomes more invested in the off-camera life of Husayn and Tāhirah, giving Husayn lessons in befriending Tāhirah. The film crew tries to retain order, but in the end, it is the disorderliness and imperfections that make the story meaningful.

The fact that this film is not linear and refuses a clear ending remind the viewer that real life doesn’t always have the perfect ending of mainstream movies. The concepts of “perfection” and “happy ending,” or even “ending,” “completion,” and “closure” are illusionist ideas. Order and structure are not necessarily part of our everyday life. They must be imposed on it, sometimes with no success. Life is filled with imperfect open ending events with no closures. Virtuous cinema, philosophical cinema could remind the viewer about such realities.

Ecopoetic Cinema

Olive Trees is a film with ecopoetic sensibilities. Its meditation on nature and the natural beauty of olive trees makes it an example of visual poetry with ecological emphasis. A survey of old and new films made by directors such as Sāmū’il Khāchīkiyān, Amīr Nādirī, Shahīd Sālis, Muhsin Makhmalbāf, and Rakhshān Banī I‛timād reveals that the themes of the love for nature, finding peace and serenity in nature, and searching for humanity in nature all appear often in Iranian cinema. However, among other art-house filmmakers, Kiyārustamī’s ecopoetic approach is prevalent. He was obviously inspired by Persian poets such as Hāfiz and Suhrāb Sipihrī who employed nature as their source of aesthetic stimulation.10See Khatereh Sheibani, The Poetics of Iranian Cinema: Aesthetics, Modernity and Film after the Revolution (London: I.B. Tauris, 2011).

As discussed, Olive Trees conveys documentary aesthetics by employing neorealist sensibilities and amateur acting that appears to be improvised. Yet, there is barely anything natural, improvised, and unpremeditated in the film. The mise-en-scène, including dialogue, acting, and most of the set design, including the façade of the newlywed couple for the on-camera sequences, were manicured by an auteur director who had inclusive artistic control over the film.

The only natural and real part of the mise-en-scene is the olive grove. As indicated, one could also argue that the grove is in fact the film’s protagonist. All of the sequences in Olive Trees are shot outdoors within nature. Even the scenes of homelife take place outdoors. When Ms. Shīvā goes to fetch Tāhirah, she finds the young woman’s grandmother sitting on the balcony behind pots of geraniums. When Tāhirah eventually shows up, she enters the house to try on a party dress. Ms. Shīvā follows her to check on her attire, but the camera remains outside of the house. Likewise, the shots of the newlyweds in their home are all done in open space, and the fictional film crew are also shown camping outside in tents under olive trees. The cast and crew are always shown in open spaces— whether in cars, walking, acting, or in conversation. Nature is home to these people. The olive grove is their resting place, and the sky is their roof. The emphasis on nature in the film is more apparent than in any other in Kiyārustamī’s oeuvre.

Figure 13: The fictional film crew is shown camping in tents beneath olive trees. A still from the film Through the Olive Trees (Zīr-i Dirakhtān-i Zaytūn), directed by ʿAbbās Kiyārustamī, 1994.

The olive has a long history in Iranian culture and Persian literature. The Achaemenid documents attest to the existence of olive trees 2500 years ago. In Middle Persian/Pahlavī language (224-651 CE), the word for olive is mentioned as Zayt. Olives are also mentioned in the Old Testament and the Quran. Poets such as Rumi and Khāqānī referred to olive as a source of enlightenment11“Zān hamī pursī charā īn mī-kunī / kih ṣuvar zayt ast u ma‛nī rushanī.” (Rumi) and beauty.12“Jān fashānand bar ān khāl u bar ān halqah-yi zulf/ ʿĀshiqān kān rukh-i zaytūnī-i zībā bīnand.” (Khāqānī)

The poems are quoted from Bahrām Girāmī, Gul u giyāh dar hizār sāl shiʿr-i fārsī: Tashbīhāt va Istiʿārāt [Flowers and Plants in a Thousand Years of Persian Poetry: Similes and Metaphors] (Tehran, Farhang-i Mu‛āsir, 2007), 571-573. In Olive Trees, Husayn eventually secures a response from the reluctant Tāhirah when they walk under the grove. The final composition of the film shows that Husayn has become enlightened under the olive trees, but the audience is not given the same privilege. Instead, the audience is rewarded to view a peaceful composition of olive trees in extreme long shot.

The olive tree, Dirakht-i Zaytūn in Persian, is the emblem of perseverance. Olive trees easily acclimatize in different climate types.13The information about olive tree and its history and significance in Iran is mostly acquired from the following two sources: Shamāmah Muhammadīfar, “Zaytūn” (Olive), Dānishnāmah-yi Jahān-i Islām, accessed June 2, 2025, https://rch.ac.ir/article/Details?id=14882; And Bahrām Girāmī, Gul u giyāh dar hizār sāl shiʿr-i fārsī: Tashbīhāt va Istiʿārāt [Flowers and Plants in a Thousand Years of Persian Poetry: Similes and Metaphors] (Tehran, Farhang-i Mu‛āsir, 2007), 571-572. In Iran, olive trees have been planted and used as a source of energy as well as for culinary, aesthetic, hygienic and medical purposes for over 3000 years. Olive trees yield fruits in the mild, rainy provinces of Gīlān and Mazandaran as well as the arid areas of southern Khurāsān, Fārs and Kirmān. They can live for over a thousand years. These evergreens thrive in locations with gusting winds and endure cold winters. In the film, the audience sees that unlike the man-made edifices, the olive trees survived the earthquake. Hence, olive trees are the insignia—both literally, and figuratively—of endurance, perseverance and longevity. Kiyārustamī’s camera is quite observant of the olive grove, often focusing more on the trees than the human characters. The constant portrayal of olive trees in deep focus, wide angle shots, long shots, medium long shots, and long takes collectively depict the integrity and diligence of olive trees.

Olive trees also symbolize peace and love. Husayn’s perseverance in his pursuit of love also bears resemblance to the nature of olive trees. The prominence of olive gardens in the film and the matching resilience of the human characters and olive trees could be seen as an allegory for Iranian/Persian art and identity, which survived and even thrived under repression in different periods of history. The allegorical significance of olive trees is discernible through the zooming of camera on the olive grove rather than highlighting the ruined houses caused by the earthquake. Like the trees, Persian art and identity survived despite sociopolitical suppression after the formation of the Islamic regime.

Figure 14: A view of Tāhirah and an olive tree. A still from the film Through the Olive Trees (Zīr-i Dirakhtān-i Zaytūn), directed by ʿAbbās Kiyārustamī, 1994. accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iAe8_O_4VZI (01:35:59).

Iranian cinema after the 1978-79 Revolution was threatened with annihilation, as initially, Khumaynī was not in favor of having a film industry in the country. He wrote about cinema as the “direct cause of prostitution, corruption, and political dependence.”14Quoted in Khatereh Sheibani, The Poetics of Iranian Cinema: Aesthetics, Modernity and Film after the Revolution (London: I.B. Tauris, 2011), 5. Hundreds of theatre houses were burned down by the Islamists during the revolution. Many theatre houses and entertainment centres were also shut down by the revolutionary forces or the government. Prominent filmmakers and actors were either exiled, secluded, or imprisoned. The film industry went into a dormant period for the first few years, and once it revived, the state-funded productions of Islamist directors such as Muhsin Makhmalbāf replaced the favorite fīlmfārsī movies of the pre-revolutionary era.

However, Iranian cinema, with its diverse range of commercial and art-house productions, revived slowly in the 1980s. For art-house cinema, the newly imposed constraints forced filmmakers to further draw on an allegorical language, known as the poetic realist aesthetics, to convey sociological or philosophical meanings. The result was aesthetically outstanding productions such as Kiyārustamī’s Through the Olive Trees. The perseverance of olive trees in the film could be understood as an allegory for the perseverance of cinema in Iran. It is worth remembering the meta-cinematic story of the film depicts the hardship a film crew endures in a half-ruined village. The fictional story of the film crew in Olive Trees is the story of filmmakers, artists, and film technicians who sacrificed a much easier lifestyle so they could revitalize Iranian cinema. Through the Olive Trees is a love story, but the subject of true love in the film is not Tāhirah, but rather nature in the form of olive trees and by extension culture and identity in the form of Iranian cinema. Olive trees are the subject of passion and love—the real protagonists of the film. Unlike previous superstars who were eradicated from the cinema screens and pushed to seclusion by the Islamic regime, the beauty of nature as the protagonist or a star, could not be eradicated. The nature, in an ecopoetic outlook, became immortalized in one of the most outstanding productions of ʿAbbās Kiyārustamī.

Through the Olive Trees problematizes conventional cinematic realism, and in a self-reflexive manner criticizes the role of filmmakers in the process of making (neo)realist films. In the end, the audience comes to the conclusion that the only authentic and real element of the film, which has been there before the intrusion of the film crew, is the nature represented and highlighted through the olive trees. Indeed, the eco-poetic representation of nature as Kiyārustamī’s camera portrays is the poetry of life.

Cite this article

Through Olive Trees is the third part of Abbas Kiarostami’s Koker trilogy, which was filmed in Koker, in the Rostam Abad region of Gilan province in Iran. What is significant in this film is its deceptively simple plot that eventually leads the viewer to thought-provoking thematics. In this meta-cinematic rural movie, Kiarostami affirmed his aptitude for side-stepping political religiosity, which was promoted in the state-funded films of the 1980s and 1990s. He embraces an authentic humanism that became a signature part of his “cinema stylo” aesthetics.