To Live Is to Rebel: Khayyām’s Rubāʿiyāt, My Favourite Cake, and the Politics of Joy in Iran

Introduction

Awareness of mortality has long served as a powerful catalyst for philosophical reflection and artistic creation. Across cultures and centuries, the certainty of death has inspired artists, thinkers, poets, and creatives alike to ask urgent questions about the meaning of life, the possibility of happiness, and the value of lived experience. Rather than retreating into nihilism or religious consolation, some of the most enduring creative works engage this awareness of finitude as a call to live more fully—to find beauty, intimacy, and truth in the fleeting moment.

This ethos underpins My Favourite Cake (Kayk-i mahbūb-i man, 2024), a contemporary Iranian film by Maryam Muqaddam and Bihtāsh Sanā‛ī’hā. Set in Tehran, the film follows Mahīn, a seventy-year-old widow who, after decades of solitude, dares to pursue love and self-expression. In the context of a society that polices aging, femininity, and desire, Mahīn’s rebellion—seeking companionship, inviting a man to her house, sharing wine and dancing—becomes a radical act of agency and presence.

Described by its directors as a film made “in praise of life,”1“My Favourite Cake. Iran, France, Sweden, Germany 2024, 97 mins. Directors: Maryam Moghaddam, Bihtāsh Sanā‛ī’hā,” BFI Southbank Programme Notes, accessed June 20, 2025, https://bfidatadigipres.github.io/new%20releases/2024/09/13/my-favourite-cake/. My Favourite Cake presents an unapologetic embrace of desire and pleasure in the face of mortality—an outlook that invites deeper reflection: What intellectual and cultural resources inform this perspective? What kind of worldview shapes the film’s portrayal of pleasure not as indulgence, but as a form of meaning-making?

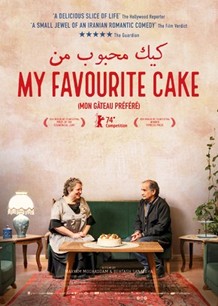

Figure 1: Poster for My Favourite Cake (Kayk-i Mahbūb-i Man), directed by Maryam Muqaddam and Bihtāsh Sanā‛ī’hā, 2024. The image captures the film’s central characters, Mahīn and Farāmarz, seated together across a modest table adorned with a cake.

This essay explores how My Favourite Cake draws on enduring currents in Persian literary and philosophical thought, particularly the legacy of ‛Umar Khayyām (1048–1131), a celebrated philosopher, poet, mathematician, and astronomer, to frame mortality as a catalyst for authentic living.

This connection to ‛Umar Khayyām’s philosophy is indeed affirmed by the directors of My Favourite Cake in their own reflections. As co-director Bihtāsh Sanā‛ī’hā notes, “Our poets, like Omar Khayyam, speak about seizing the moment. As Iranians, we are always thinking about this because we live in a country where the future is unpredictable. Bad things might be waiting for us, but we are used to living in the moment and enjoying it.”2“My Favourite Cake,” Lansdown Film Club, accessed June 20, 2025, https://www.lansdownfilmclub.org/whats-on/myfavouritecake. Khayyām uses his Rubāʿiyāt (quatrains) to reflect on enduring existential questions, especially the transient and uncertain nature of human life. Composed in eloquent and compact verses, the Rubāʿiyāt weave together themes of mortality, doubt, and desire, offering a poetic philosophy that urges readers to embrace the present moment rather than defer meaning to the hereafter. In Khayyām’s verse, earthly pleasures—such as drinking wine, enjoying nature, and indulging in sensual intimacy—are not distractions but existential responses to the fact of life’s finitude and humans’ unescapable uncertainty about its meaning. Importantly, Khayyām frequently positions these themes in direct tension with dominant religious doctrines concerning abstinence, divine judgment, and the afterlife. In this sense, My Favourite Cake functions as a contemporary reflection of Khayyām’s carpe diem principle. Filmed without state approval, this film offers a quiet but radical act of defiance within a socio-political structure that tightly monitors and restricts women’s autonomy, agency, and desire. In her rebellion against societal, religious, and gendered expectations, Mahīn becomes a contemporary heir to Khayyām’s call for present-tense living. Her pursuit of love and pleasure, though tender and deeply human, directly challenges the restrictive legal and religious norms in post-revolutionary Iran. This defiance, whether conscious or not, carries the imprint of Khayyām’s worldview, who in his verses—often dismissed by religious authorities as hedonistic—performs a subversive critique of theological orthodoxy by placing significant importance on earthly experiences and human agency.3Daryūsh Shāyigān, Panj Iqlīm-i Ḥuzūr [The Five Realms of Presence] (Tehran: Farzān-i Rūz, 2001), 43-44. As Khayyām boldly declares in one of his verses:

Fardā ‛alam-i nifāq tay khāham kard,

Bā mū-yi sipīd qasd-i may khāham kard,

Paymānah-yi ‛umr-i man bih haftād risīd,

In dam nakunam nishāt, kay khāham kard?

Tomorrow, I will cast off the robe of hypocrisy;

With my white hair, I will raise a toast,

The cup of my life has reached seventy—

If I don’t rejoice now, then when will I?4All translations of Khayyām’s Rubāʿiyāt are by the author of this article, unless otherwise noted.

The following sections provide a deeper examination of how My Favourite Cake reflects the philosophical and poetic legacy of Khayyām, revealing a rich, multi-layered cultural and intellectual continuity. Through their shared emphasis on mortality, joy, and defiance, both works offer a rich meditation on what it means to live truthfully under conditions of repression.

Contextual Overview: Subversive Echoes Across Eras

Although separated by nearly a millennium, The Rubāʿiyāt of ‛Umar Khayyām and My Favourite Cake emerge from similarly repressive sociopolitical conditions. Both works speak from within societies governed by orthodoxy, moral surveillance, and tightly controlled narratives around mortality, pleasure, and freedom.

Living during the Seljuk era, Khayyām made significant contributions to algebra and calendar reform, yet it is his Rubāʿiyāt—a collection of quatrains that continues to provoke and inspire. His verses, often written in a skeptical and disarmingly candid tone, challenge dominant religious doctrines and advocate for embracing sensual and intellectual pleasures despite societal or theological prohibitions.5Dariush Shayegan, Panj Iqlīm-i Ḥuẓūr [The Five Realms of Presence] (Tehran: Farzan-e Rooz, 2001), 43-44.

My Favourite Cake was produced in contemporary Iran under a similar climate of intense ideological censorship. Iranian cinema, particularly since the 1979 Revolution, has long been subject to strict controls, including mandatory hijab regulations on screen and restrictions on the depiction of intimacy. By portraying an elderly woman acknowledging her agency and seeking connection, intimacy, and joy, the film boldly challenges these cinematic and moral constraints—an act that led to serious legal repercussions for its filmmakers.6Bahar Momeni, “A Slice of Life: The Lasting Bittersweet Taste of My Favorite Cake,” IranWire, accessed June 20, 2025, https://iranwire.com/en/guest-blogger/135764-a-slice-of-life-the-lasting-bittersweet-taste-of-my-favorite-cake/.

Despite their different historical contexts, both the Rubāʿiyāt and My Favourite Cake subvert the dominant religious and political orthodoxies of their time. Each work poses profound questions about mortality, freedom, and authenticity, offering ephemeral pleasure not as a distraction but as philosophical resistance. In such similar socio-political settings, both Khayyām and the creators of My Favourite Cake address the same fundamental questions: How should one live in the shadow of death? What does it mean to pursue joy and authenticity in a repressive world? How might art illuminate the deeper truths obscured by dogmatic and authoritarian systems of control?

Ephemeral Existence – The Fleeting Nature of Life

While My Favourite Cake highlights the ephemerality of life through its various manifestations—growing old, physical decline, solitude, isolation, and ultimately, death—Khayyām’s verses achieve a similar effect by repeatedly reminding us of the brevity and fragility of our time on earth.

Afsūs kih bīfāyidah farsūdah shudīm,

Vaz dās-i sipihr-i sarnigūn sūdah shudīm;

Dardā u nidāmatā kih tā chashm zadīm,

Nābūdah bih kām-i khvīsh, nābūdah shudīm!7Sādiq Hidāyat, ed. Tarānah-hā-yi Khayyām [The Songs of Khayyām] (Tehran: Amīr Kabīr, 1963), 74, quatrain 19.

Alas, we were worn down, wasted in vain,

Crushed beneath heaven’s inverted blade again;

Ah, sorrow and regret—for in the blink of an eye,

Before tasting life’s joy, we vanished!

Mahīn, the protagonist of My Favourite Cake, faces the twilight of life directly. After decades of widowhood, Mahīn makes a bold and unexpected choice: she confronts the woman she has become, and dares to be honest with herself. In a radical act of self-liberation, she embraces her long-silenced yearning for intimacy and connection and, without apology, begins to seek love on her own terms. This determination to disregard the strong taboos surrounding old age and womanhood, as well as to seek intimacy and humbly pursue her last chances at love and happiness, is a response to the simple yet profound realization that her time is short. Mahīn’s late-life romance is suffused with an awareness that every moment is precious precisely because it will not last long.

Throughout the film, subtle cues highlight Mahīn’s marginalization as she struggles to feel truly alive. During a gathering to celebrate her belated birthday, her friends present her with a blood pressure monitor. This gift serves as a poignant reminder of her advancing age and the societal expectations associated with it. The scene is infused with dark humor, as Mahīn’s friends are also widows, highlighting the shared experiences of aging and loneliness within their social circle.8John McDonald, “My Favourite Cake,” Everything the Artworld Doesn’t Want You to Know, December 5, 2024, accessed June 20, 2025, https://www.everythingthe.com/p/my-favourite-cake.

Figure 2: Mahīn chats with her friends during a lively lunch gathering. A still from the film My Favourite Cake (Kayk-i Mahbūb-i Man), directed by Maryam Muqaddam and Bihtāsh Sanā‛ī’hā, 2024. (00:07:21).

Later that night, in a video call with her daughter, Mahīn attempts to share a tender gesture—a handwoven quilt made for her grandson—but is met with distracted detachment. Her daughter barely registers the offering, cuts her off mid-conversation, and offers perfunctory advice: to wear new clothes “in the house” and to stay indoors because of a new disease. These moments accumulate into a painful realization: Mahīn is seen only as a fragile, aging woman who needs to be protected, not as someone capable of love, longing, or renewal.

Figure 3: Mahīn holds up a handmade crocheted blanket. A still from the film My Favourite Cake (Kayk-i Mahbūb-i Man), directed by Maryam Muqaddam and Bihtāsh Sanā‛ī’hā, 2024. (00:12:40).

The emotional disregard she receives from her closest relations drives home the quiet violence of being rendered invisible. In the wake of this indifference, immediately after her conversation with her daughter, Mahīn steps into the dim light of her bathroom, confronts her own reflection, and begins to apply bold makeup—not out of vanity, but as an act of reclamation. In doing so, she asserts her right to feel, to desire, and to be seen—not as a relic of the past, but as a woman still alive to possibility.

As Mahīn’s journey unfolds into a seemingly meaningful and intimate connection with Farāmarz, the viewers, like Mahīn herself, are drawn into a joyous celebration of love and companionship, marked by a night of passionate drinking, dancing, eating, and conversation. This emotional peak is abruptly shattered by Farāmarz’s sudden death—the film’s most vivid and jarring reminder of life’s fragility. Only hours after spending the “best night of his life”9My Favourite Cake, dir. Maryam Muqaddam and Bihtāsh Sanā‛ī’hā (Caractères Productions, Watchmen Productions, HOBAB, Fīlmsāzān-i Javān, 2024), 00:57:32.—an intimate evening with his newfound love—Farāmarz, instead of carrying the night into morning with his beloved, unexpectedly succumbs to death and embarks on a journey of no return. His passing underscores death’s omnipresence, intruding just as joy and intimacy take root, and leaving both Mahīn and the viewer with a sobering awareness of life’s impermanence.

This cinematic exploration of life’s impermanence finds a profound literary parallel in numerous quatrains of Khayyām.

Yak qatrah-yi āb būd bā daryā shud,

Yak zarrah khāk bā zamīn yiktā shud,

Āmad shudan-i tu andar īn ‛ālam chīst,

Āmad magasī padīd u nāpaydā shud.10Sādiq Hidāyat, ed. Tarānah-hā-yi Khayyām [The Songs of Khayyām] (Tehran: Amīr Kabīr, 1963), 80, quatrain 41.

A drop of water—it joined the sea.

A speck of dust—it became one with the earth.

What is your coming and going in this world?

A fly, it appeared—then vanished.

Much like a drop dissolving into the ocean of nothingness, or a speck of dust merging with the earth, the human journey—our arrival and departure—is brief and, ultimately, insignificant. As Dāryūsh Shāyigān notes in his work Panj Iqlīm-i Huzūr (The Five Realms of Presence), Khayyām, when faced with the profound futility of existence, offers two interwoven yet distinct responses, reflecting the dual nature of human experience. One is a poignantly blunt and negative view that cuts through all illusions and hopeful fantasies with a blinding, unsparing force of disillusionment, unveiling the powerful presence of death to reveal the fragility of human beings in life. The other is a constructive effort to salvage a sense of presence, however fragile, from the world’s wreckage and disorder. Khayyām is merciless in his negation: What does it matter whether this world is created or eternal, when we are headed toward a destiny we have no reliable way of knowing?11Dariush Shayegan, Panj Iqlīm-i Ḥuẓūr [The Five Realms of Presence] (Tehran: Farzan-e Rooz, 2001), 52-53. From this unflinching awareness, Khayyām draws a logical and deeply human conclusion: since certainty eludes us and permanence is an illusion, all we can do is embrace the present, finding joy, beauty, and meaning in the fleeting moments of life while they last.

Shādī bitalab kih hāsil-i ʿumr damī-st,

Har zarrah zi khāk-i Kayqubādī u Jamī-st,

Ahvāl-i jahān va asl-i in ʿumr kih hast,

Khvābī u khiyālī u farībī u damī-st.12Sādiq Hidāyat, ed. Tarānah-hā-yi Khayyām [The Songs of Khayyām] (Tehran: Amīr Kabīr, 1963), 103, quatrain 109.

Seek joy, for life’s yield is but a breath.

Every particle of dust was once a Jamshīd or a Kay Qubād.

The state of the world and the truth of this life—

Are but a dream, a fantasy, a deception, a fleeting moment.

Khayyām reminds us that no one, and no life situation, can exempt a human being from the law of mortality, as even the most significant and powerful figures in history have ultimately been reduced to mere objects in the hands of time.

In addition to highlighting life’s impermanence and the inevitability of death, Khayyām frequently contemplates the material transformation of the body after death. Several of his quatrains imagine human remains—once reduced to dust—being reshaped into clay, then fashioned into everyday vessels such as jugs or pitchers. This recurring imagery of the kūzah (jug) and clay serves as a potent metaphor in both Persian literary and Islamic traditions, evoking the idea that humans are formed from the earth and will ultimately return to it.13Nick M. Loghmani, Omar Khayyam: On the Value of Time (New York: Routledge India, 2022), 18–22. These symbols not only affirm the cyclical nature of life and matter but also make the reality of death intimately tangible, embodied in the ordinary objects we hold in our hands. At the same time, Khayyām subtly undermines belief in an afterlife or metaphysical continuation of the soul, offering instead a vision of posthumous existence as dissolution into earth and reconstitution as inert form. One quatrain poignantly captures this vision:

Zān kūzah-yi may kih nīst dar vay ẓararī,

Pur kun qadahī, bikhur, bi-man dih digarī.

Zān pīshtar, ay sanam, kih dar rahguzarī,

Khāk-i man u tu kūzah kunad, kūzah-garī.14Sādiq Hidāyat, ed. Tarānah-hā-yi Khayyām [The Songs of Khayyām] (Tehran: Amīr Kabīr, 1963), 90, quatrain 68.

From that jug of wine that brings no harm,

Fill a cup, drink, and hand me another.

Before, O beloved, on a passway,

A potter fashions a jug from your dust and mine.

In this quatrain, Khayyām envisions death not as a metaphysical journey, but as a material transformation—our bodies, once reduced to dust, reshaped into a humble jug. This potent image collapses the boundary between the animate and inanimate, reminding us that the matter of our being persists, not as soul, but as clay—molded, repurposed, and woven back into the cycle of nature.

This philosophy reverberates in Farāmarz’s fate, which—uncannily—mirrors Khayyām’s worldview. Shortly after sharing moments of joyful communion with Mahīn, Farāmarz dies unexpectedly. Earlier that evening, while drinking wine and admiring the vitality of Mahīn’s lush garden, he wistfully expresses a longing for such a space. Mahīn generously replies, “Well, this garden is yours.”15My Favourite Cake, dir. Maryam Muqaddam and Bihtāsh Sanā‛ī’hā (Caractères Productions, Watchmen Productions, HOBAB, Fīlmsāzān-i Javān, 2024), 00:55:10. What seems at first a warm gesture becomes, in retrospect, a prophetic one. Farāmarz dies that very night, and by becoming part of the garden—symbolically rooted in the soil he admired—he fulfills both his promise to bring a plant and Khayyām’s vision of posthumous transformation. Just as Khayyām imagines human remains reconstituted as vessels of pleasure, Farāmarz becomes part of the garden’s living beauty, folded into the earth and its quiet continuities.

Pā bar sar-i sabzah tā bih khvārī nanahī,

Kān sabzah zi khāk-i lālah rūyī rastah ast.16Sādiq Hidāyat, ed. Tarānah-hā-yi Khayyām [The Songs of Khayyām] (Tehran: Amīr Kabīr, 1963), 88, quatrain 63.

Tread not with scorn upon the living grass,

For it has sprung from the dust of a tulip-faced one.

Or

In kūzah chu man ʿāshiq-i zārī būdah-st,

Dar band-i sar-i zulf-i nigārī būdah-st.

In dastah kih bar gardan-i ū mī-bīnī,

Dastī-st kih bar gardan-i yārī būdah-st.17Sādiq Hidāyat, ed. Tarānah-hā-yi Khayyām [The Songs of Khayyām] (Tehran: Amīr Kabīr, 1963), 91, quatrain 72.

This jug, like me, has been a desperate lover,

Captivated by the tresses of a beloved

The handle you see upon its neck,

Was once a hand that once embraced a beloved’s neck.

In his work titled The Songs of Khayyām (Tarānah-hā-yi Khayyām) influential twentieth-century writer Sādiq Hidāyat notes that Khayyām’s worldview stands in stark contrast to the Sufi belief that everything in the universe serves a divine purpose and that human life is guided by a higher mission. Instead, for Khayyām, existence is composed of transient particles, bound to dissolve and recombine in the indifferent cycles of nature. In the wine jug, he sees not merely a vessel but the reconstituted dust of once-beautiful bodies, their essence now animated by the wine it holds. This vision evokes both awe and sorrow, inviting readers to embrace the present before it vanishes into oblivion.18Sādiq Hidāyat, ed. Tarānah-hā-yi Khayyām [The Songs of Khayyām] (Tehran: Amīr Kabīr, 1963), 34.

A similar sensibility surfaces in My Favourite Cake through Farāmarz’s revelation that he once made wine with a friend, sealing it in clay jugs and burying them in the earth. When Mahīn playfully suggests they do the same in her garden, the gesture seems lighthearted—until it gains weight in hindsight. Farāmarz, who dies unexpectedly that night, symbolically becomes the jug: returned to the soil, folded into the cycle of impermanence that Khayyām so often evokes. The scene transforms a moment of intimacy into a meditation on mortality, underscoring the film’s awareness that joy is always shadowed by loss.

Figure 4: Mahīn opens a large bottle of homemade wine with a joyful smile. A still from the film My Favourite Cake (Kayk-i Mahbūb-i Man), directed by Maryam Muqaddam and Bihtāsh Sanā‛ī’hā, 2024. (00:44:33).

In this light, the acknowledgment of mortality in both works does not lead to despair or nihilism. Instead, it becomes the ground for a different kind of existential courage. Having faced the inevitability of death, both the Rubāʿiyāt and My Favourite Cake turn to a deeper question: how to live meaningfully within life’s fleeting limits. In doing so, they embrace joy—both sensual and relational—not as a denial, but as a defiance: an act of choosing beauty and connection precisely because they are impermanent.

Seizing the Moment: A Response to Life’s Uncertainty

Even though Khayyām in his Rubāʿiyāt unapologetically confronts readers with the fragility of human existence, he does not leave them stranded within this unsettling truth. Instead, his candid acknowledgment serves as an invitation to live life to the fullest. Ultimately, Khayyām’s reflections encourage embracing and savoring life’s fleeting yet exquisite moments as the most meaningful human response to existential uncertainty. Nick M. Loghmani, in his work Omar Khayyam: On the Value of Time, emphasizes Khayyām’s message that existence is fleeting, and, thus, the precious moments of life must be cherished.19Nick M. Loghmani, Omar Khayyam: On the Value of Time (New York: Routledge India, 2022), 25. Loghmani adds that Khayyām’s central message in addressing life’s perplexing ambiguities is unambiguous: life is brief and impermanent, and therefore its beautiful, fleeting moments deserve deep appreciation. In a world defined by constant flux, Khayyām suggests that the only path to true equanimity lies in embracing the present fully and without illusion. Loghmani further contends that, for Khayyām, life’s transience grants each moment inherent worth, made meaningful when lived through experiences of art, love, and beauty. Thus, the act of savoring these moments may be understood as a mode of aesthetic engagement with temporality.20Nick M. Loghmani, Omar Khayyam: On the Value of Time (New York: Routledge India, 2022), 26-27.

Figure 5: Mahīn and Farāmarz recline side by side, hands clasped, silently savoring their shared presence after dancing together. A still from the film My Favourite Cake (Kayk-i Mahbūb-i Man), directed by Maryam Muqaddam and Bihtāsh Sanā‛ī’hā, 2024. (01:13:33).

My Favorite Cake also underscores a keen awareness of time’s transience through several poignant moments. Shortly after her initial encounter with Farāmarz, Mahīn repeatedly urges him to return quickly, even during the briefest separations—whether he steps away to visit the pharmacy, use the bathroom, or take a shower. She seems genuinely aware of how limited their time is, and having already lost three decades of her life in solitude, she does not want to miss a single moment of the joy and happiness of being with a beloved companion. For instance, after their heartfelt exchange in the car, when Farāmarz steps out to go to the pharmacy, Mahīn remains seated, gazing through the rain-speckled windshield. The droplets shimmer with soft hues of yellow, red, and blue—reflections of a world that suddenly feels more alive. Mahīn smiles, not merely at the colors, but at the tenderness they seem to embody. Through this quiet interplay of rain and light, the film subtly suggests how Farāmarz’s presence brings warmth and color back into her life.

Figure 6: Rain blurs the city lights into soft, colorful orbs as Mahīn sits alone in the car. A still from the film My Favourite Cake (Kayk-i Mahbūb-i Man), directed by Maryam Muqaddam and Bihtāsh Sanā‛ī’hā, 2024. (00:36:09).

Also, when Mahīn goes to the kitchen to prepare fruit and wine glasses while talking to Farāmarz, she notices him standing and, with visible concern on her face, asks, “Why did you get up? I was just about to serve you something.”21My Favourite Cake, dir. Maryam Muqaddam and Bihtāsh Sanā‛ī’hā (Caractères Productions, Watchmen Productions, HOBAB, Fīlmsāzān-i Javān, 2024), 00:45:35. Mahīn appears anxious that Farāmarz might leave, bringing their brief time together to an abrupt end. However, upon realizing that he has no intention of departing, she smiles with visible relief.

Figure 7: Mahīn in the kitchen notices Farāmarz standing in the middle of the living room. A still from the film My Favourite Cake (Kayk-i Mahbūb-i Man), directed by Maryam Muqaddam and Bihtāsh Sanā‛ī’hā, 2024. (00:45:45).

Further, just before the dance scene, when Farāmarz says he’s going to the bathroom, Mahīn says, “Come back soon,” and, moments later, teasingly urges him, “Farāmarz, what’s taking you so long? Come on, we want to dance!”22My Favourite Cake, dir. Maryam Muqaddam and Bihtāsh Sanā‛ī’hā (Caractères Productions, Watchmen Productions, HOBAB, Fīlmsāzān-i Javān, 2024), 01:09:20. As Farāmarz rejoined Mahīn, the camera glides alongside their gentle movements, rotating through the house to reveal how Mahīn’s once-muted space is now bathed in warm light—alive with joy, intimacy, and renewed vitality. In stark contrast, the scene following Farāmarz’s sudden death captures the devastating rupture of that transformation. When Mahīn realizes he is not merely asleep but truly gone, she rushes from the room in panic. The camera lingers, panning through the dimly lit home, now hushed and hollow—an echo of the solitude that once defined her existence. Her desperate cry, “Don’t do this to me,”23My Favourite Cake, dir. Maryam Muqaddam and Bihtāsh Sanā‛ī’hā (Caractères Productions, Watchmen Productions, HOBAB, Fīlmsāzān-i Javān, 2024), 00:21:35. reverberates through the silence as the camera drifts for nearly two minutes, capturing the eerie stillness. It eventually settles on Mahīn, weeping at his bedside, trying in vain to revive him. With Farāmarz’s absence, the warmth and color he had brought vanish, replaced by a void as profound as the one his presence had briefly dispelled.

This emotional intensity helps explain why their bond deepens so quickly over the span of just a few hours, culminating in Mahīn referring to themselves as “lovers.”24My Favourite Cake, dir. Maryam Muqaddam and Bihtāsh Sanā‛ī’hā (Caractères Productions, Watchmen Productions, HOBAB, Fīlmsāzān-i Javān, 2024), 00:51:00. In the kitchen scene where they share a glass of wine, Mahīn recalls a past attempt at making wine on her own, noting that the result was unsuccessful. She then proposes that she and Farāmarz make wine together and bury the jugs in her garden, mentioning an old belief that if two lovers make wine jointly, “the more in love they are, the finer their wine will be.” Farāmarz responds affirmatively, implicitly acknowledging their romantic connection by remarking, “How interesting! Maybe ours will be good too!”25My Favourite Cake, dir. Maryam Muqaddam and Bihtāsh Sanā‛ī’hā (Caractères Productions, Watchmen Productions, HOBAB, Fīlmsāzān-i Javān, 2024), 00:51:10. While their behavior may seem hasty, rushing to call their feelings love, it stems from an acute awareness that time is fleeting.

Wine also plays a symbolic role in the film—its presence in conversation, its consumption, and its liberating effect on the characters all serve as catalysts for moments of self-revelation. In most of the scenes involving Mahīn and Farāmarz, wine appears as a recurring motif. Mahīn has carefully preserved a large jar of fine, deep red wine, awaiting the opportunity to share it with a companion. To her, the act of drinking serves as a means of suspending temporal concerns, allowing her to transcend both past and future in favor of a conscious engagement with the present. In an interview, Sanā‛ī’hā mentions, “Drinking wine is a simple sign of enjoying life, which is why we put it in our story.” Also, Muqaddam concurs, “[Khayyām] talks a lot about drinking wine and forgetting the madness of the world, because life is too short, and you’ll be gone forever, sooner or later.”26Nick Chen, “My Favourite Cake: The Iranian Rom-Com That Earned Its Makers a Travel Ban,” AnOther, September 13, 2024, accessed June 20, 2025, https://www.anothermag.com/design-living/15861/my-favourite-cake-maryam-moghaddam-behtash-seanaeeha-interview-film.

Figure 8: Mahīn and Farāmarz raise their glasses in a toast, sharing a joyful moment over wine and fruit in her cozy kitchen. A still from the film My Favourite Cake (Kayk-i Mahbūb-i Man), directed by Maryam Muqaddam and Bihtāsh Sanā‛ī’hā, 2024. (00:49:20).

Echoing this perspective, wine in Khayyām’s Rubāʿiyāt serves not merely as a symbol of earthly pleasure but as a paradoxical conduit to mindfulness and presence. Far from a marginal motif, wine is a recurring and foundational element in Rubāʿiyāt: forty quatrains depict the act of drinking, and twenty-seven others reference terms for wine—may, bādah, and sharāb—underscoring both its symbolic weight and literal presence in Khayyām’s corpus.27Omar Khayyam and Kuros Amouzgar, The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam for Students of Persian Literature: Bilingual Edition with Transliteration of the Persian (Farsi) (Bethesda, MD: Ibex Publishers, 2014), 13.

In the film, Khayyām’s worldview also shines through in several moments involving wine, most vividly in the garden scene where Mahīn and Farāmarz share a drink. Before taking another sip, Farāmarz pauses and gently pours a portion of his wine into the garden’s soil. When asked why, he replies simply, “This is the portion for the ones who are beneath the soil. In the old days, they’d say: with every glass you drink, offer a sip to those who’ve departed.” Mahīn, touched by the sentiment, smiles and says, “How beautiful!” She pours a sip and adds, “This is my share.”28My Favourite Cake, directed by Maryam Muqaddam and Bihtāsh Sanā‛ī’hā (Caractères Productions, Watchmen Productions, HOBAB, Fīlmsāzān-i Javān, 2024), 00:57:20.

Figure 9: Mahīn and Farāmarz in the garden. Farāmarz pours a cup of wine onto the earth—an offering in remembrance of the dead. A still from the film My Favourite Cake (Kayk-i Mahbūb-i Man), directed by Maryam Muqaddam and Bihtāsh Sanā‛ī’hā, 2024. (00:57:40).

This evocative gesture echoes Khayyām’s poetic logic, in which wine becomes more than indulgence—it serves as a medium for contemplating mortality and communing with the dead, as if in drinking with them, we are reminded that we will one day join them, and perhaps, in some way, already have. This quiet ritual of remembrance and Farāmarz’s acknowledgment of mortality can be read as an embodiment of this verse with striking clarity:

Yārān bih muvāfaqat chu dīdār kunīd,

Bāyad kih zi dust yād-i bisyār kunīd;

Chun bādah-yi khushgavār nūshīd bih ham,

Nūbat chu bih mā rasad, nigūnsār kunīd.29Sādiq Hidāyat, ed. Tarānah-hā-yi Khayyām [The Songs of Khayyām] (Tehran: Amīr Kabīr, 1963), 94, quatrain 83.

When you, my friends, gather in harmony,

Remember your absent friend often and warmly.

And when you drink that sweet, delightful wine—

Turn the cup down when it comes to my time.

Deep in his heart, Farāmarz might know that this is the last time he will drink wine, thus offering this view to Mahīn, as if he already senses that he will soon become part of the garden’s soil. In doing so, he signals to Mahīn that she may continue to share the ritual with him even after he has passed, when his presence lingers in the earth beneath her feet. Furthermore, there are several subtle cues in various scenes that foreshadow Farmaraz’s death. For instance, in their conversation in the garden, he promises Mahīn that he will be there daily, sitting in the garden and watching over her. He also speaks of bringing her a bush of stock flowers to plant in the garden’s “pure soil.” Additionally, among all the herbs, he expresses a fondness for mint: “Mint is such a good plant. Once you plant it, it stays forever. It’s always there,” Mahīn says. “Nothing lasts forever,” Farāmarz replies. “Yes, it does!” Mahīn insists. “Like what?” Farāmarz asks. Mahīn pauses, as if recalling the quiet truth of transience, as if realizing that only nothingness endures—and answers, “I don’t know… maybe nothing.”30My Favourite Cake, dir. Maryam Muqaddam and Bihtāsh Sanā‛ī’hā (Caractères Productions, Watchmen Productions, HOBAB, Fīlmsāzān-i Javān, 2024), 00:55:30.

In retrospect, Farāmarz’s promises seem to have been fulfilled not in life but in death—he becomes the plant buried in the earth, the eternal mint, and the silent presence watching Mahīn from within the garden. It is no surprise, then, that from the moment Mahīn meets Farāmarz, the film subtly shifts its visual perspective. For instance, when Mahīn first enters her backyard—on that rainy night—the camera adopts the garden’s point of view, as though we are witnessing her through Farāmarz’s eyes, soon to be embedded in the garden’s soil.

Figure 10: Mahīn enters the door to her house under the cover of night and rain for the first time after meeting Farāmarz. A still from the film My Favourite Cake (Kayk-i Mahbūb-i Man), directed by Maryam Muqaddam and Bihtāsh Sanā‛ī’hā, 2024. (00:38:00).

In the final scene, this transformation is further underscored: Mahīn is depicted from behind, sitting and gazing into the garden, wearing a dress adorned with stock flowers, as if wrapped in the memory of Farāmarz’s final gift.

Figure 11: The back of Mahīn’s head frames the screen as she sits alone, facing the garden, now quiet and sunlit (Last scene of the film). A still from the film My Favourite Cake (Kayk-i Mahbūb-i Man), directed by Maryam Muqaddam and Bihtāsh Sanā‛ī’hā, 2024. (01:32:00).

This intimate layering of symbolism—where love, the fleetingness of the moment, and mortality are interwoven with nature—sets the stage for a deeper reading of the film within its broader cultural framework. It reveals how the quiet act of embracing joy, however small or ephemeral, becomes a meaningful gesture in the face of life’s transience. Yet in a society where joy and intimacy are tightly policed, particularly for women, such gestures take on added weight. What begins as personal becomes unmistakably political, and what feels poetic becomes subversive when placed against the backdrop of contemporary societal constraints.

Socio-Political Resistance Through Individual Agency

Another significant parallel between Khayyām’s Rubā‛iyāt and My Favourite Cake lies in their shared engagement with—and defiance of—restrictive socio-political and moral frameworks. Both works mount their resistance through subtle, embodied challenges to dominant norms, portraying joy, companionship, and sensuality not merely as private indulgences but as radical affirmations of life and personal freedom—a declaration of autonomy in the face of repressive authority.

Although the Rubāʿiyāt was not publicly circulated during Khayyām’s lifetime, its verses nonetheless posed a quiet yet profound challenge to the dominant religious dogmas of the highly orthodox Seljuk era (c. 1037–1194), privileging the richness of temporal life over abstract theological promises of the afterlife. The Seljuk Empire, while politically expansive, actively reinforced Sunni orthodoxy and curtailed earlier traditions of rationalist and speculative thought. As Bertold Spuler explains, it was during this period that powerful institutions like the Nizāmiyah madrasas in Baghdad were established to promote orthodox Sunni doctrine and suppress theological dissent, particularly the lingering Muʿtazilite rationalism that had flourished in Persia for centuries. Through these state-backed schools and court patronage, viziers such as Nizām al-Mulk institutionalized a system of favoritism that rewarded compliant scholars and marginalized dissenters. Scholars whose views diverged from sanctioned orthodoxy risked losing their posts and their patrons.31Bertold Spuler, Iran in the Early Islamic Period: Politics, Culture, Administration and Public Life Between the Arab and the Seljuk Conquests, 633–1055 (Leiden: Brill, 2014), 145–146. In this climate, Khayyām’s skeptical and hedonistic quatrains offered a subtle yet potent critique of the restrictive religious and political order that sought to dictate not only belief but the very terms of philosophical inquiry.

As Mehdi Aminrazavi notes in The Wine of Wisdom, Khayyām lived at the cusp of this cultural shift, when the intellectual openness of the Islamic Golden Age gave way to increased dogmatism and theological rigidity. In contrast to contemporaries like Al-Ghazzālī, who worked to consolidate mainstream Sunni beliefs through Sufi-infused orthodoxy, Khayyām’s verse articulated a philosophical skepticism that quietly resisted these enforced norms.32ehdi Aminrazavi, The Wine of Wisdom: The Life, Poetry and Philosophy of Omar Khayyam (Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 2005), 84-85.

Importantly, Khayyām turned to verse as a safer medium for ideas that would have been dangerous to express openly in prose. While not all the quatrains attributed to Khayyām are authentically his, his quatrains often satirize dogma and highlight the limits of human knowledge, setting him at odds with the dominant intellectual currents of his time, especially the contentious debates between the Muʿtazilites and Ashʿarites, two major Islamic schools that clashed over reason, free will, and divine justice.33Mehdi Aminrazavi, The Wine of Wisdom: The Life, Poetry and Philosophy of Omar Khayyam (Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 2005), 85.

This tension between rebellion and restraint is reflected not only in the content of Khayyām’s verses but also in their chosen form. The rubāʿī—a popular form of quatrain in Persian poetry known for its brevity, precision, and rhetorical force—has long been a favored vehicle for unorthodox expression. Its direct and compact structure allows the poet to unveil philosophical and existential truths without hesitation, mirroring the boldness and clarity often found in the meanings these quatrains carry.34Mehdi Aminrazavi, The Wine of Wisdom: The Life, Poetry and Philosophy of Omar Khayyam (Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 2005), 51. As Peter Avery notes, this form was widely embraced by thinkers “who were in some degree non-conformists opposed to religious fanaticism,” and who used the verse form to veil their dissent.35Peter Avery and John Heath-Stubbs, The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyam (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1981), 9.

Aminrazavi notes that although Khayyām outwardly practiced Islam—reportedly even performing the pilgrimage (hajj), likely as a way to demonstrate his faith and shield himself from allegations of heresy circulating among his contemporaries—his quatrains unmistakably reveal an agnostic, if not outright atheistic, worldview.36Mehdi Aminrazavi, The Wine of Wisdom: The Life, Poetry and Philosophy of Omar Khayyam (Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 2005), 29. As Hidāyat further observes, Khayyām’s verses offer a rare and enduring example of secular thought in a Persian literary tradition often shaped by mystical or moral allegory. In contrast to poets like Hāfiz, whose wine-soaked metaphors often serve as vehicles for mystical allusion or at least allow such alternative spiritual interpretations, Khayyām speaks about wine with striking clarity and directness. His references to wine, intoxication, and sensual pleasure are not cloaked in symbolic ambiguity but are instead literal affirmations of earthly joy in the face of mortality. Hidāyat emphasizes that Khayyām’s poetry resists the indirect, allegorical style typical of the Persian canon, articulating materialist and existential concerns with a rare plainness and unembellished force.37Sādiq Hidāyat, ed. Tarānah-hā-yi Khayyām [The Songs of Khayyām] (Tehran: Amīr Kabīr, 1963), 56. Khayyām’s rejection of the false dichotomy between piety and pleasure—and his unapologetic use of symbols like wine and revelry—was so provocative that it not only unsettled religious authorities in his own time but continues to spark debate today. The subversive force of his poetry has elicited polarized responses from Iranian intellectuals and the broader public over centuries, ranging from reverence to repudiation. For instance, Sādiq Hidāyat regards Khayyām as the embodiment of a rebellious Aryan spirit resisting Semitic religious doctrines.38Sādiq Hidāyat, ed. Tarānah-hā-yi Khayyām [The Songs of Khayyām] (Tehran: Amīr Kabīr, 1963), 27-28. In contrast, critics such as Siddīqī Nakhjavānī condemn Khayyām for what they view as irreverent hedonism and overt challenges to theological authority.39Rizā Siddīqī Nakhjavānī, Khayyām-pindārī va pāsukh-i afkār-i qalandarānah-yi ū (Tabriz, Iran: Sorush, 1931), 25-40. These polarized interpretations underscore the enduring rebellion at the heart of Khayyām’s work: his commitment to sensual and existential freedom in a context shaped by asceticism and spiritual discipline.

Sādiq Hidāyat frames Khayyām’s worldview as deeply rooted in his background in mathematics and astronomy, suggesting that the poet viewed the universe as a product of random particle assembly, caught in eternal cycles of formation and dissolution. This cosmic indifference is reflected in verses such as:

Bāz āmadanat nīst, chu raftī raftī.

There is no return—once you are gone, you are gone.

Or

Chun ʿāqibat-i kār-i jahān nīstī-st.40Sādiq Hidāyat, ed. Tarānah-hā-yi Khayyām [The Songs of Khayyām] (Tehran: Amīr Kabīr, 1963), 32.

For the end of the world’s work is nothingness.

Dawrī kih dar [ū] āmadan u raftan-i māst,

Ū rā nah nahāyat, nah badāyat paydāst,

Kas mī-nazanad damī dar-īn maʿnī rāst,

Kīn āmadan az kujā u raftan bih kujāst!41Sādiq Hidāyat, ed. Tarānah-hā-yi Khayyām [The Songs of Khayyām] (Tehran: Amīr Kabīr, 1963), 71, quatrain 10.

This cycle in which our coming and going takes place—

Has neither a beginning nor an end in sight.

No one speaks truthfully, even for a moment,

Of where this coming is from and where this going leads.

Or

Tā chand zanam bih rūyi daryā-hā khisht?

Bīzār shudam z but-parastān-i kunisht.

Khayyām! kih guft duzakhī khvāhad būd?

Kih raft bih duzakh u kih āmad z bihisht?42Sādiq Hidāyat, ed. Tarānah-hā-yi Khayyām [The Songs of Khayyām] (Tehran: Amīr Kabīr, 1963), 70, quatrain 6.

How long must I lay bricks upon the sea?

I’m weary of the idol-worshippers of the sanctuary.

Khayyām! Who said there will be a hell?

Who has gone to hell—and who returned from paradise?

Khayyām’s outright denial—or, at the very least, profound skepticism—regarding the afterlife, and by extension one of the foundational tenets of religious belief, constitutes a radical departure from Islamic eschatological doctrine.

In the medieval Islamic context, doubting the idea of Resurrection was a radical departure from the mainstream, essentially a rejection of a cornerstone of Islamic theology. Yet Khayyām often writes as if the body and its fate were all that we have, with “death…confined to the body” and no promise of an afterlife.43Abhik Maiti, “Out, Out Brief Candle! The Fragility of Life and the Theme of Mortality and Melancholia in Omar Khayyam’s ‘Rubaiyat’,” International Journal of English Language, Literature in Humanities 5, no. 8 (August 2017): 486. While he adopted a more conservative stance in his scientific writings—likely as a means of safeguarding his social position—his poetry reveals no such restraint.44Nick M. Loghmani, Omar Khayyam: On the Value of Time (New York: Routledge India, 2022), 19.

In one verse, he ridicules divine creation by likening God to a deranged potter who smashes his own fragile vessels:

In kūzah-gar-i dahr chunīn jām-i latīf

Mīsāzad u bāz bar zamīn mī-zanad-ash.45Sādiq Hidāyat, ed. Tarānah-hā-yi Khayyām [The Songs of Khayyām] (Tehran: Amīr Kabīr, 1963), 83, quatrain 43.

This potter of fate crafts such a delicate vase,

Only to dash it to the ground in spite.

Elsewhere, he portrays humanity as helpless puppets in the hands of a capricious cosmic force:

Mā luʿbatigān-īm u falak luʿbat-bāz,

Az rūyi haqīqatī nah az rūyi majāz;

Yak-chand dar-īn basāt bāzī kardīm,

Raftīm bih sandūq-i ʿadam yak-yak bāz!46Sādiq Hidāyat, ed. Tarānah-hā-yi Khayyām [The Songs of Khayyām] (Tehran: Amīr Kabīr, 1963), 85, quatrain 50.

We are but puppets, and the firmament the puppeteer,

Not in metaphor, but in the truest sense, clear.

For a brief while we played upon this stage,

Then, one by one, returned to the chest of nothingness.

His revolutionary ideas culminate in a verse that dismisses debates about religion and blasphemy as ultimately meaningless—childish diversions that distract from the real uncertainties of existence, and ultimately asserts that even God is nothing more than a word, lacking any reliable or verifiable source.

Sāniʿ bih jahān-i kuhnah hamchun zarfī-st.

Ābī-st bih maʿnī u bih zāhir barfī-st;

Bāzīchah-yi kufr u dīn bih tiflān bispār,

Bugzar z maqāmī kih khudā ham harfī-st!47Sādiq Hidāyat, Tarānah-hā-yi Khayyām [The Songs of Khayyām] (Tehran: Amīr Kabīr, 1963), 42.

The maker of this worn-out world is like a vessel—

Its meaning fluid, though on the surface, like snow.

Leave the game of faith and blasphemy to children;

Move beyond such stations—where even God is just a word.

Notably, although skeptical of the prevailing beliefs of his time, Khayyām does not claim certainty or advocate a particular ideology. Instead, he acknowledges the fundamental limits of human understanding. This perspective is consistent across multiple quatrains, where Khayyām reflects on the inescapable limits of human knowledge and the futility of metaphysical speculation:

Asrār-i azal rā nah tu dānī u nah man,

Vīn harf-i muʿammā, nah tu khvānī u nah man.48Sādiq Hidāyat, ed. Tarānah-hā-yi Khayyām [The Songs of Khayyām] (Tehran: Amīr Kabīr, 1963), 70, quatrain 7.

The secrets of eternity—neither you know, nor I;

The answer to this riddle—neither you can read, nor I.

Also:

Ān bīkhabarān kih durr-i maʿnī suftand,

Dar charkh bih anvāʿ sukhan-hā guftand;

Āgah chu nagashtand bar asrār-i jahān,

Avval zanakhī zadand u ākhir khuftand.49Sādiq Hidāyat, ed. Tarānah-hā-yi Khayyām [The Songs of Khayyām] (Tehran: Amīr Kabīr, 1963), 72, quatrain 14.

Those heedless ones [who thought that] they grasped truth’s pearls,

Spoke countless words beneath the turning sky;

Yet never touched the secrets of this world—

They muttered at first, and in the end, slept away.

These verses frame human existence as uncertain and ultimately unknowable—an existential stance that privileges earthly meaning-making over religious promises of salvation. This celebration of present-tense joy, sensual freedom, and defiance of orthodoxy finds a powerful contemporary parallel in My Favourite Cake. Just as Khayyām’s verses challenge the theological and moral structures of his time by affirming the dignity of earthly experience, the film confronts Iran’s modern socio-political restrictions on bodily autonomy, female agency, and private pleasure. Turning now to the cinematic context, we can trace how Mahīn’s rebellion mirrors Khayyām’s ethos, reimagining the pursuit of love, joy, and personal freedom as subversive acts within a heavily censored and patriarchal society.

The film’s Berlinale synopsis underscores the inherently political nature of its narrative, describing it as the story of “a woman who decides to live out her desires in a country where women’s rights are heavily restricted.”50Vassilis Economou, “My Favourite Cake Wins the Eurimages Award at the Berlinale Co-Production Market,” Cineuropa, February 15, 2022 accessed June 20, 2025, https://cineuropa.org/en/newsdetail/421980/. In this light, Mahīn’s decision to pursue love—and to open her heart and home for a night of dancing, wine, and intimacy—is nothing short of revolutionary, both personally and politically.51Nick Chen, “My Favourite Cake: The Iranian Rom-Com That Earned Its Makers a Travel Ban,” AnOther, September 13, 2024, accessed June 20, 2025, https://www.anothermag.com/design-living/15861/my-favourite-cake-maryam-moghaddam-behtash-seanaeeha-interview-film. In a society that polices female desire and autonomy, such an act becomes a radical intervention that challenges a patriarchal culture expecting widows and older women to become invisible, to “disappear and remain modest as they age.”52Zebib K. Abraham, “My Favourite Cake,” Writers Mosaic Magazine, October 30, 2024, accessed June 20, 2025, https://writersmosaic.org.uk/reviews/my-favourite-cake/. The film pointedly refuses to punish or shame its protagonist for her desires—a powerful act of resistance within the context of Iranian cinema. Instead, Mahīn’s pursuit of pleasure and companionship is treated as both natural and profoundly human.

Figure 12: Mahīn sits silently next to a stranger on a bench at the bakery. The metal racks in the foreground frame them like bars. A still from the film My Favourite Cake (Kayk-i Mahbūb-i Man), directed by Maryam Muqaddam and Bihtāsh Sanā‛ī’hā, 2024. (00:16:35).

Iranian society under the Islamic Republic imposes strict moral codes on individuals: a woman of any age hosting an unrelated man behind closed doors, sharing alcohol (which is strictly illegal), or even appearing without hijab in front of him—all defy the country’s dominant socio-political norms. These restrictions are not incidental but have been institutionally enforced since the 1979 Revolution. As Pardis Minuchehr explains, “From the very outset of the revolution, the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance (MCIG) attempted to define the role of women in the new regime’s ideological understanding of cinema specifically and to regulate cultural policies in the Islamic Republic more broadly.”53Pardis Minuchehr, “Women’s Cinema in Post-Revolutionary Iran,” in Cinema Iranica (Encyclopaedia Iranica Foundation, 2024), accessed June 20, 2025, https://cinema.iranicaonline.org/article/14251-2/. Also, Negar Mottahedeh notes, “Attached to traditional Islamic values and confined by the enforcement of modesty laws, women’s bodies became subject to a system of regulations that aimed to fabricate the modesty of Iranian women into the hallmark of the new Shi’ite nation.”54Negar Mottahedeh, “Iranian Cinema in the Twentieth Century: A Sensory History,” Iranian Studies 42, no. 4 (2009): 534. These state-imposed fabrications have profoundly shaped not only Iranian cinema but also the very representation of women within it.

The film strives to remain faithful to the private, often hidden dimensions of Iranian life, shedding light on experiences long suppressed by censorship and cultural norms. As Sanā‛ī’hā explains, “Alcohol is forbidden in Iran, but Iranians drink it. It’s just being honest about life. By being honest, you face consequences. But that is life in Iran.” He adds, “For the last 45 years, Iranian cinema has had to show Iranian women wearing a hijab inside their house, even when they sleep… It’s a lie. We want to show how Iranian women really live.”55Nick Chen, “My Favourite Cake: The Iranian Rom-Com That Earned Its Makers a Travel Ban,” AnOther, September 13, 2024, accessed June 20, 2025, https://www.anothermag.com/design-living/15861/my-favourite-cake-maryam-moghaddam-behtash-seanaeeha-interview-film. In revealing these realities, the film quietly affirms the dignity of everyday Iranian life and allows viewers to see themselves truthfully represented on screen. Unsurprisingly, despite being banned from official release in Iran, a leaked version spread rapidly and became a major topic of discussion, especially among women.

This commitment to portraying lived reality culminates in one of the film’s most poignant and transgressive moments. Among the film’s most memorable scenes is an intimate moment in which Mahīn and Farāmarz, intoxicated by wine, sing and dance together. Earlier in the evening, Mahīn is visibly anxious about the neighbors and the weight of social expectations. In a striking visual moment, she is shown speaking to her neighbor through a metal gate. Mahīn stands inside her dimly lit home—warm, private, and intimate—while the outside is drowned in an unnatural green light, the kind often used in lighting of religious spaces such as mosques and shrines. This color contrast instinctively separates Mahīn’s inner world from the external pressures of public morality and religious surveillance. Yet, as the night progresses—and under the influence of both the wine and the emotional connection—she relinquishes those fears. Their dance becomes a liberating, defiant embrace of private joy and intimacy, marking a significant shift in Mahīn’s character.

Figure 13: Mahīn, talking to her neighbor who has come to question the noise. A still from the film My Favourite Cake (Kayk-i Mahbūb-i Man), directed by Maryam Muqaddam and Bihtāsh Sanā‛ī’hā, 2024. (00:51:50).

Critic Zebib Abraham notes that the film’s most “daring feature” lies precisely in this tender, physical portrayal of the elderly couple: “Mahīn and Farāmarz… want emotional and physical connection at a time of their lives when they are supposed to have no desire, and in a country that suppresses the expression of desire.” Their joyous dance breaks long-standing taboos in Iranian cinema surrounding female sexual subjectivity and aging.56Zebib K. Abraham, “My Favourite Cake,” Writers Mosaic Magazine, October 30, 2024, accessed June 20, 2025, https://writersmosaic.org.uk/reviews/my-favourite-cake/.

The dance is accompanied by Farīdūn Farrukhzād’s song “Dar-rā vā nimīkunam” (I Won’t Open the Door), which deepens the emotional and symbolic layers of the scene.57Farīdūn Farrukhzād, “Dar-rā vā nimīkunam [I Won’t Open the Door],” lyrics by Abulqāsim Ilhāmī, music by Hādī Āzarm, released ca. 1970s, accessed June 20, 2025, https://parand.se/?p=18537. The lyrics evoke a fierce desire to protect a private moment of connection from the intrusions of the outside world:

If the moon comes down from the sky and knocks at my door,

If the bird of luck and fortune flies above my head,

If the thunder in the sky starts to roar,

If a thousand screams rain down on me—

Since you’re my guest, I won’t open the door.

You are the companion of my soul, I won’t open the door.

Figure 14: Mahīn and Farāmarz dance joyfully in her living room, their faces lit with laughter and warmth. A still from the film My Favourite Cake (Kayk-i Mahbūb-i Man), directed by Maryam Muqaddam and Bihtāsh Sanā‛ī’hā, 2024. (00:01:12).

The choice of Farrukhzād’s song carries profound political and cultural resonance. A beloved pre-revolutionary singer, poet, and openly queer public figure, Farrukhzād embodied resistance to censorship, gender norms, and authoritarian control. His assassination in exile in 1992—widely believed to have been orchestrated by the Iranian Islamic regime—transformed him into a potent symbol of silenced dissent.58“Former IRGC Minister Admits to Directing International Assassinations,” IranWire, February 1, 2025, accessed June 20, 2025, https://iranwire.com/en/politics/139765-former-irgc-minister-admits-to-directing-international-assassinations/. Within this context, the inclusion of “Dar-rā vā nimīkunam” amplifies the characters’ private act of rebellion, linking their fleeting joy to a broader history of resistance, vulnerability, and suppressed expression in Iranian society. Mahīn’s dance thus becomes a fearless, unapologetic assertion of presence, feeling, and desire in defiance of forces that seek to repress them.

In fact, Mahīn’s journey toward understanding, embracing, and revealing her truth demands that she navigates multiple layers of censorship, pushing back against both internalized and external forms of control. She must confront her own guilt and hesitation, as well as the ever-present threat of the state’s moral surveillance, symbolically embodied in the watchful eye of a nosy neighbor.

This dual structure of repression—internal censorship, shaped by years of ideological conditioning, and external censorship, enforced through legal and social sanctions—frames Mahīn’s rebellion. Her actions become emblematic of a broader feminist challenge to Iran’s gendered and institutional constraints. The Women’s movement surrounding the film in the contemporary Iranian context cannot be overlooked: in recent years, particularly following the “Woman, Life, Freedom” protests of 2022, Iranian women and artists have increasingly defied compulsory hijab laws and resisted conservative censorship. Yet even in this context, My Favourite Cake’s boldness is almost unprecedented among Iranian films produced inside the country. The film was produced independently “without the [Iran] Culture Ministry’s permission, in defiance of the country’s strict ideological censorship and hijab regulations for actresses.”59“Iran Summons My Favorite Cake Film Directors to Revolutionary Court,” Iran International, February 12, 2025, accessed June 20, 2025, https://www.iranintl.com/en/202502128369.

It is no wonder, then, that the filmmakers and their team faced severe repercussions for this film. They were barred from travel and later summoned to Tehran’s Revolutionary Court on charges including producing a film with obscene content, violating public morality and ethics, “promoting immorality,” and even “propaganda against the Islamic Republic.”60“Iran Summons My Favorite Cake Film Directors to Revolutionary Court,” Iran International, February 12, 2025, accessed June 20, 2025, https://www.iranintl.com/en/202502128369. Ultimately, both directors, Muqaddam and Sanā‛ī’hā along with the film’s producer, were sentenced to suspended prison terms on charges largely stemming from the film’s depiction of women without hijab and its submission to international festivals without prior domestic approval.61“Iranian Guild Condemns My Favorite Cake Film Convictions,” IranWire, April 8, 2025, accessed June 20, 2025, https://iranwire.com/en/society/140204-iranian-guild-condemns-my-favorite-cake-film-convictions/. The filmmakers’ equipment was confiscated, and other crew members, including actors and the cinematographer, were fined. These charges make clear that the film is viewed as a direct challenge to the sociopolitical order of the Islamic Republic. This defiance is vividly rendered in a pivotal scene where the morality police attempt to arrest young women for improper hijab in a public park, just as Mahīn passes by in pursuit of love. Her bold intervention to protect the young women serves as a stark illustration of the everyday battles Iranian women face. The scene powerfully evokes the arrest and death of Mahsā Amīnī—a 22-year-old woman who died in the custody of the morality police—an event that ignited the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement and occurred during the very days the film was being shot in Tehran. While some critics argue that the scene disrupts the film’s otherwise subtle, lyrical, and whimsical tone, it stands as a crucial moment: both a reflection of the socio-political reality surrounding Mahīn’s story and a timely expression of collective resistance.62Martha Bird, “Berlinale 2024: My Favourite Cake,” Film Fest Report, February 19, 2024, accessed June 20, 2025, https://film-fest-report.com/berlinale-2024-my-favourite-cake-maryam-moghaddam-behtash-sanaeeha-review/. In this light, Mahīn’s transformation can be seen not merely as personal, but as deeply political.

Figure 15: Mahīn stands before morality police officers as a young woman ushered into a van. A still from the film My Favourite Cake (Kayk-i Mahbūb-i Man), directed by Maryam Muqaddam and Bihtāsh Sanā‛ī’hā, 2024. (00:23:40).

Conclusion

The parallels between My Favourite Cake and ‛Umar Khayyām’s Rubāʿiyāt reflect a deep cultural continuity in how Iranian artists, across centuries, have turned to joy, ephemerality, and mortality as tools for resistance and meaning-making. Beginning with moments of quiet domesticity, the film soon unfolds into a bold expression of rebellion, echoing the silent defiance many Iranian women enact in their everyday lives. In portraying an elderly woman who seeks love and intimacy without shame, the film challenges not only narrative expectations but also entrenched sociopolitical taboos. It openly defies the codes of post-revolutionary Iranian cinema, which have long suppressed representations of female desire, aging, and autonomy. Without explicit imagery or overt political rhetoric, it insists that women—even older, widowed women—have the right to feel, to want, and to live fully.

This cinematic act of defiance resonates profoundly with the philosophical spirit of Khayyām. In his Rubāʿiyāt, Khayyām invokes the imagery of wine, gardens, and love not merely to celebrate life’s fleeting pleasures, but to challenge the accepted tenets of religious orthodoxy. He satirizes theological doctrines that postpone fulfillment to a speculative afterlife, instead urging his readers to embrace the here and now. Unlike the mystical ambiguity often found in Sufi verse, Khayyām’s voice is strikingly literal—so much so that his work has endured centuries of censorship, forced allegorization, and moral discomfort, all efforts to sanitize a worldview that steadfastly refused to conform. In this sense, both the film and the poems challenge what is culturally or theologically forbidden, whether in thought or bodily experience, as a means of reclaiming authenticity. In their worlds, pleasure becomes a form of truth-telling, and joy becomes an act of resistance. As Mahīn violates the unwritten rules of widowhood and as Khayyām pours wine in the face of dogma, both affirm a right to presence, feeling, and freedom.

This contemplation finds its most intimate expression in the quiet details of Mahīn’s home. Hanging on the wall above her green velvet couch are three embroidered frames—repeatedly visible throughout the film, including the pivotal moment when Farāmarz first enters her house. These works, according to a conversation of author of this article with co-director Bihtāsh Sanā‛ī’hā, were handmade by Maryam Muqaddam’s grandfather, who was an admirer of Khayyām. Each embroidery, while visually modest, bears philosophical weight. The leftmost reads something akin to “One must savor every moment of life and share that joy with others,” stitched with the date Urdībihisht 1352 (May 1973), a nod to a hopeful pre-revolutionary past. The rightmost contains the Zoroastrian ethic, “Good thoughts, good words, good deeds,” a moral compass that predates Islamic doctrine and persists in the Iranian ethical imagination.

The center frame, at first glance the most ambiguous, carries a profound weight. As Sanā‛ī’hā explained, it features lines by Bertolt Brecht:

“…Alas, we

Who wished to lay the foundations of kindness

Could not ourselves be kind.

But you, when at last it comes to pass

That man can help his fellow man,

Do not judge us

Too harshly.”63Bertolt Brecht, To Posterity, 1938, quoted in George Fish, “Alas, we who wished to lay the foundations of kindness…” New Politics, July 3, 2011, accessed June 20, 2025, https://newpol.org/alas-we-who-wished-lay-foundations-kindness/.

This verse—delivered as a message to future generations—is a haunting acknowledgment of historical failure and enduring hope. Embedded within it is the voice of an older generation, one that tried and perhaps faltered, yet still entrusted the dream of compassion and liberation to those who would follow. In this way, the three frames—crafted by a grandfather inspired by Khayyām, chosen by filmmakers who reimagine joy as subversion, and centered in a story of late-life intimacy—form a symbolic triad of inherited values. They quietly stitch together a lineage of dissent that spans generations: from Khayyām’s poetic irreverence to Brecht’s political yearning, and finally to Mahīn and Farāmarz’s shared longing for connection. This transmission of subversive ethics across time—through embroidery, through poetry, through film—becomes a radical act in itself.

Together, The Rubāʿiyāt and My Favourite Cake resist the erasure of lived experience under systems of control. They reclaim intimacy and immediacy not only as aesthetic choices but as philosophical imperatives. Both works insist that the right to joy, to desire, to love, and to live fully—even under repression—is not just essential, but the very essence of life itself in its most unadulterated form.

In this way, My Favourite Cake becomes not only a story of transgressive love but also a vessel of cultural memory. It is a quiet yet resounding testament to how Persian intellectual traditions—embodied in the embroidered maxims on a widow’s wall, or in Khayyām’s heretical verse—continue to animate acts of beauty, resistance, and radical authenticity in the face of constraint.

Figure 16: Mahīn and Farāmarz sit side by side in the parlor, engaged in a conversation. Behind them hang three framed pieces of embroidery in Persian. A still from the film My Favourite Cake (Kayk-i Mahbūb-i Man), directed by Maryam Muqaddam and Bihtāsh Sanā‛ī’hā, 2024. (00:43:35).

Cite this article

This paper explores the philosophical and cultural affinities between My Favourite Cake (Kayk-i mahbūb-i man, 2024), a contemporary Iranian film by Maryam Muqaddam and Bihtāsh Sanā‛ī’hā, and The Rubāʿiyāt, a celebrated 11th–12th century collection of quatrains by Persian poet and philosopher ‛Umar Khayyām. Through a comparative analysis, it examines how both works center themes of mortality, fleeting joy, and existential defiance to mount a resistance against sociopolitical and religious constraints. In portraying Mahīn—a seventy-year-old widow who dares to pursue love, intimacy, and self-expression—the film mirrors Khayyām’s worldview, in which sensual pleasures and present-tense living are not indulgences but meaningful responses to life’s impermanence.

The film’s boldness lies not only in its subject matter but also in its refusal to conform to the ideological and cinematic restrictions imposed in post-revolutionary Iran. Similarly, Khayyām’s quatrains, often accused of heresy, question divine justice, religious dogma, and metaphysical certainty, privileging human agency and the here-and-now over promises of an afterlife. Both works challenge dominant frameworks—whether theological or political—through an aesthetics of joy, embodiment, and immediacy.

Ultimately, this paper argues that My Favourite Cake continues a centuries-old Persian tradition of dissent, finding in art a means of resistance. By drawing on Khayyām’s legacy, the film reclaims intimacy and pleasure as acts of truth-telling within a repressive context. In doing so, it demonstrates how cultural memory and philosophical inheritance can inform and empower contemporary artistic expression.