Transcending Realities The Poetic Evolution of Love in Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī’s Cinema (The Pear Tree and Dear Cousin is Lost)

Introduction

Silence, often perceived merely as the absence of sound or speech, functions in narrative and literary contexts as a complex and generative phenomenon. It is not simply muteness or void; rather, it constitutes a deliberate absence within the semiotic chain that invites interpretation and engagement. In written narratives, silence refers to elements that are left unstated, unrepresented, or absent in the text, yet still influence the reader’s understanding of the story. It may manifest as omitted lines, words, or events that shape interpretation and generate meaning through what is not explicitly told.

In literary studies, silence has been addressed from multiple angles. Scholars such as Politi (1998),1J. Politi, “The Silencing of Silence,” in Anatomies of Silence: Selected Papers of the Second HASE International Conference on Autonomy of Logos: Anatomies of Silence, ed. Ann Cacoullos and Maria Sifianou (Athens: Hellenic Association for Semiotics of the Arts and Letters, 1998), 29–45. Massey (2003),2K. R. Massey, “Shattering the Empty Vessel: Absence and Language in Addie’s Chapter of Faulkner’s as I Lay Dying,” (Master’s thesis, North Carolina State University, 2003). Schwalm (1998),3H. Schwalm, “The Silence of Many Words: Metafictional Interior Monologues in the Postmodernist British Novels of Julian Barnes and Kazuo Ishiguro,” in Anatomies of Silence: Selected Papers of the Second HASE International Conference on Autonomy of Logos: Anatomies of Silence, ed. Ann Cacoullos and Maria Sifianou (Athens: Hellenic Association for Semiotics of the Arts and Letters, 1998), 128–36. Tseng (2002),4M.-Y. Tseng, “The Representation of Silence in Text,” Dong Hwa Journal of Humanistic Studies, no. 2 (2000): 103–24. and Glenn (2004)5K. M. Glenn, Discourse of Silence in Alcanfor and “Te deix, amor, la mar com a penyora” (California: Wake Forest University, 2004). examine various theoretical dimensions of silence, while sociolinguistic researchers—including Bruneau (1973, 1988, 2007),6Thomas J. Bruneau, “Communicative Silences: Forms and Functions,” Journal of Communication 23 (1973): 17–46; Thomas J. Bruneau and S. Ishii, “Communicative Silences: East and West,” World Communication 17, no. 1 (1988): 1–33. Originally presented at the International Communication Association Conference, Honolulu, HI, 1985; Thomas J. Bruneau, “Functions of Communicative Silences: A Critical Review; a Revision of a Paper: ‘Functions of Communicative Silences: East and West,’” paper presented at Harmony, Diversity, and Intercultural Communication Conference, Harbin, China, June 2007. Huckin (2002),7Thomas Huckin, “Textual Silence and the Discourse of Homelessness,” Discourse & Society 13, no. 3 (2002): 347–72. Kurzon (1997, 2007),8Dennis Kurzon, Discourse of Silence (Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing, 1998); Dennis Kurzon, “Towards a Typology of Silence,” Journal of Pragmatics 39, no. 10 (2007): 1673–88; Dennis Kurzon, “Peters Edition V. Batt: The Intertextuality of Silence,” International Journal for the Semiotics of Law 20 (2007): 285–303. Tannen (1985),9Deborah Tannen and Miriam Saville-Troike, Perspectives on Silence (Norwood, NJ: Ablex, 1985). Saville-Troike (1985, 1994),10M. Saville-Troike, “Silence,” in The Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics, ed. R. E. Asher and J. M. Y. Simpson (Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1994), 9345–47; M. Saville-Troike, The Ethnography of Communication: An Introduction (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 1985); M. Saville-Troike, “The Place of Silence in an Integrated Theory of Communication,” in Perspectives on Silence, ed. Deborah Tannen and M. Saville-Troike (Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing, 1985), 3–18. and Jaworski (1993, 1997, 2000)11Adam Jaworski, ed., Silence: Interdisciplinary Perspectives (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1997); Adam Jaworski, “‘White and White’: Metacommunicative and Metaphorical Silences,” in Silence: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, ed. Adam Jaworski (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1997), 381–401; Adam Jaworski, “Silence and Small Talk,” in Small Talk, ed. Justine Coupland (Routledge, 2000), 110–132.—focus primarily on silence in speech and language use. These approaches, though valuable, often overlook the function of silence as a narrative strategy that structures the story itself. This study, by contrast, investigates the role of narrative silence in shaping fictional worlds, emphasizing how stories are structured by what is intentionally left untold.

Key theorists in literary and narratological studies have explored related concepts. Wolfgang Iser’s notion of the “blanks” (1978)12Wolfgang Iser, The Act of Reading: A Theory of Aesthetic Response (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1978). highlights the reader’s active role in completing indeterminate spaces left by the author, while Gérard Genette’s concept of gap-reading (1982)13Gérard Genette, Figures of Literary Discourse, trans. Marie-Rose Logan (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982). emphasizes narrative omissions that demand imaginative supplementation. Meir Sternberg (1987)14Meir Sternberg, The Poetics of Biblical Narrative: Ideological Literature and the Drama of Reading (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987). describes a network of informational gaps through which meaning emerges via the reader’s active reconstruction. Lubomír Doležel (1995)15Lubomír Doležel, “Fictional Worlds: Density, Gaps, and Inference,” Style 29, no. 2 (1995): 201–14. and David Herman (2009)16David Herman, Basic Elements of Narrative (Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, 2009). consider these gaps as inherent features of fictional worlds rather than flaws. Similarly, Denis Kurzon (1997), Michal Ephratt (2018), and Thomas Huckin (2002) demonstrate that silence—whether as blank spaces, pauses, or rhetorical gaps—produces meaning precisely through its absence, functioning as a semiotic and communicative tool. Literary examples, such as the blank pages in Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy or William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying, illustrate how silence foregrounds unspoken or unshown content, eliciting interpretive and imaginative activity from the reader.

Building on these perspectives, silence in narrative can be understood as a cognitive and semiotic mechanism: it creates a space where meaning is not delivered directly but constructed through the reader’s or viewer’s engagement. By leaving elements unstated, narrative silence stimulates the mind to anticipate, infer, and conceptually complete missing information. Drawing on Sadeghi’s typology (2008, 2010, 2013, 2015),17Leila Sadeghi, “The Denotative Discourse of Silence from a Linguistic Perspective (Intersection of Silence in Social Interaction and Narrative Silence) [Guftimān-i dilālī-i sukūt az dīdgāh-i zabānshināsī (taqātu‘-i sukūt dar taʿāmul-i ijtimāʿī va sukūt-i rivāyī)],” Majallah-yi Pazhūhish-i ʿUlūm-i Insānī 10, no. 24 (Fall–Winter 2008): 163–183; Leila Sadeghi, “Narrative Function of Silence in Story Structure,” Quarterly Journal of Comparative Language and Literature (Linguistic Essays) 1, no. 2 (Summer 2010): 69–88; Leila Sadeghi, Discursive Function of Silence in Contemporary Persian Literature [Kārkārd-i guftimānī-i sukūt dar adabiyāt-i muʿāsir-i fārsī] (Tehran: Naqsh-i Jahān, 2013); Leila Sadeghi, “Interaction of Verbal and Visual Modes in the Discourse of Contemporary Persian Visual Poetry: A Cognitive Poetics Approach [Taʿāmul-i shīvah-hā-yi kalāmī va tasvīrī dar guftimān-i shiʿr-i dīdārī-i Fārsī-i muʿāsir bā rūykard-i shiʿr-shināsī shinākhtī],” (PhD diss., University of Tehran, Department of General Linguistics, 2015). this study distinguishes structural, semantic, and implicational forms of silence in cinematic and literary narratives, each contributing differently to audience engagement and meaning-making. Cognitive research provides a framework for understanding these processes, showing that just as the mind reconstructs incomplete visual or sensory input, it similarly interprets narrative gaps to form coherent understandings. In this sense, silence is not merely an aesthetic or formal device but a cognitive tool, mobilizing attention, memory, and inferential reasoning to generate meaning from absence.

Discursive Silence: The Link Between the Brain and Narrative

Human sensory experiences are mediated through complex perceptual mechanisms that allow the mind to construct coherent wholes from fragmented or incomplete information. The unconscious perceptual system enables the organization of visual and auditory inputs into structured forms, a concept formalized as Gestalt theory by Max Wertheimer (1923)18Max Wertheimer, Laws of Organization in Perceptual Forms (Berlin: Psychologische Forschung, 1923). and further developed by Wolfgang Köhler (1929),19Wolfgang Köhler, Gestalt Psychology (New York: Liveright, 1929). Kurt Koffka (1935),20Kurt Koffka, Principles of Gestalt Psychology (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1935). and Wolfgang Metzinger (1936).21Wolfgang Metzger, Laws of Seeing, trans. Lothar Spillmann et al. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009). The term Gestalt, meaning “shape” or “form” in German, reflects the theory’s emphasis on perceiving integrated patterns rather than isolated elements. According to Todorović,22Dejan Todorović, “Gestalt Principles,” in Encyclopedia of Perception, ed. E. Bruce Goldstein, (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2008), 381–384. humans perceive the world as nested, complex scenes composed of smaller components within broader contexts, yet the mind organizes these elements into coherent wholes through Gestalt principles.23Dejan Todorović, “Gestalt Principles,” Scholarpedia 3, no. 12 (2008): 5345. Within this framework, the principle of closure, in particular, illustrates how the brain completes incomplete or occluded elements, enabling perception of a unified object even when parts are missing.24Kurt Koffka, Principles of Gestalt Psychology (New York: Harcourt, Brace & Company, 1935; repr. Milan: Mimesis International, 2014), 632. This process, which relies on the interaction of closure and continuity, demonstrates a universal cognitive tendency to seek patterns and maintain perceptual coherence. This tendency underlies not only visual perception but also narrative comprehension.

One reason children enjoy playing hide-and-seek is related to the brain’s perceptual tendency to complete what is only partially given—a process explained by the Gestalt principle of closure. Even when an object is not fully visible, the mind infers its continued existence, deriving satisfaction from resolving the gap between absence and presence. Infants respond positively to such games, but as they grow older, the increasing predictability of outcomes modifies the game’s structure.25Diane Rogers-Ramachandran and Vilayanur S. Ramachandran, “The Neurology of Aesthetics,” Scientific American Mind 18, no. 2 (2008): 74. This same principle of closure extends into other cognitive and aesthetic activities, including puzzles, riddles, problem-solving, and discovery. In these cases, the brain derives pleasure not simply from perceiving hidden or fragmented elements, but from actively “closing” gaps to construct a coherent whole. For this reason, the so-called “principle of perceptual problem-solving” can be understood as a cognitive manifestation of closure: humans find it inherently rewarding to resolve what is incomplete, whether in visual perception, play, or intellectual inquiry.

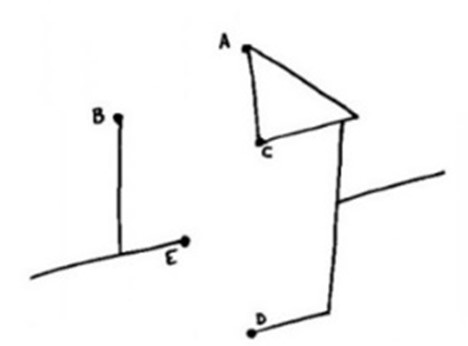

Figure 1-1: Principle of Closure

Consider a triangle outlined in black behind a white triangle (Figure 1-1). On the retina—the light-sensitive surface at the back of the eye—the image initially appears fragmented. However, the brain does not perceive the gaps as empty spaces. Instead, it seamlessly integrates the broken segments into a single, unified shape, filling in missing portions based on surrounding texture, color, and illumination.26Luiz Pessoa and Peter de Weerd, eds., Filling-in: From Perceptual Completion to Cortical Reorganization (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 1. As Bradley argues that our perceptual system seeks to complete partially occluded visual forms, deriving cognitive satisfaction when enough cues are present for the mind to infer missing elements—but if too much information is missing, the viewer fails to integrate the parts into a coherent whole.27Steven Bradley, Design Fundamentals—Elements, Attributes, & Principles: A Beginner’s Guide to Graphic Communication (Boulder, CO: Vanseo Design, 2013). Interestingly, if all elements are explicitly provided, the closure mechanism remains inactive, and the cognitive satisfaction derived from mentally filling in gaps does not occur.

Neurologically, this reconstructive capacity reflects the brain’s handling of incomplete sensory input. As Stephen Grossberg explains, blind spots in the visual field arise from gaps in photoreceptor coverage on the retina, yet the brain compensates seamlessly, producing a continuous perceptual experience.28Stephen Grossberg, “Filling-In the Forms: Surface and Boundary Interactions in Visual Cortex,” in Filling-in: From Perceptual Completion to Cortical Reorganization, ed. Luiz Pessoa and Peter de Weerd (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 16. This principle of completion extends beyond visual perception to textual and auditory domains, where the mind naturally interpolates missing elements to construct coherent meaning even when information is partial or fragmented. Silence, at its core, refers to what is not explicitly uttered in the semiotic chain yet is still received as meaning. It does not signify mere muteness or absence but rather functions as a constitutive gap within the textual system—an absence that stimulates the reader’s cognitive and imaginative faculties. As Spolsky observes, “the construction of new meaning arises not merely from collaboration among different domains of the brain, but from the very presence of gaps and fissures within the text, which lead to innovation.”29Ellen Spolsky, “Darwin and Derrida: Cognitive Literary Theory as a Species of Post-Structuralism,” Poetics Today 23, no. 1 (2002): 31. Silence thus operates at the interface between narrative and cognition: meaning emerges not only from what is present but also from what is withheld, and interpretive dynamism depends upon this tension between absence and presence.30David Herman, Basic Elements of Narrative (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009), 137–160.

According to Ray Kurzweil, the neocortex continuously predicts what will happen next in the world. In doing so, it detects information consistent with expectation, allowing humans to perceive what they anticipate and to attend selectively to expected stimuli. Consequently, human narratives mirror these cognitive predictions and possess a neurobiological foundation, while unanticipated elements often remain unnoticed, forming cognitive blind spots.31Ray Kurzweil, How to Create a Mind, unabridged ed. (Brilliance Audio, 2012), 1. He further emphasizes that the neocortex’s repeated cortical columns detect and generate hierarchical and networked patterns, enabling humans to link fragmented observations into coherent structures and conceptually reconstruct missing information. This predictive function aligns with Boyd’s observation that humans have an innate propensity to recognize patterns, integrating previously acquired environmental information to comprehend the world and their relationship to it.32Brian Boyd, “Patterns of Thought: Narrative and Verse,” in Cognitive Literary Science: Dialogues between Literature and Cognition, ed. Michael Burke and Emily T. Troscianko (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 49. Together, these findings indicate that narrative gaps—such as omitted events or unresolved actions—actively engage evolved cognitive mechanisms, prompting audiences to infer, complete, and interpret the story-world, just as the visual system reconstructs fragmented retinal images into unified percepts.

Building on these foundational perceptual processes, the principle of closure also underpins how humans engage with more abstract and symbolic forms of information. Activities such as connecting dots, solving riddles, and uncovering hidden patterns do more than exercise visual or motor skills—they cultivate higher-order cognitive functions, including reasoning, pattern recognition, and problem-solving. By actively inferring missing elements and integrating them into a coherent whole, the mind practices the same reconstructive processes that operate in visual perception and narrative comprehension. In this way, closure functions as both a perceptual and cognitive tool, shaping the way humans interpret fragmented or incomplete information across domains, from play and learning to storytelling and literary engagement (Figure 1-2).

Figure 1-2: Connecting Key Points to Enhance Cognitive Abilities in Children

In cinematic narratives, similar to the way children connect the dots in games, segments of a narrative function as key nodes that viewers mentally link to construct the structural and semantic Gestalt of the film. This allows audiences to infer unstated or unseen elements within the narrative. For instance, in The Pear Tree (Dirakht-i Gulābī, 1998) the recognition of key conceptual metaphors as nodes creates a structural Gestalt: the protagonist’s life is initially shaped not just by the literal “destiny of the pear tree” but by the metaphorical “destiny of the spider’s web.” The proximity of the web to the tree branches directs the trajectory of the narrative, leading the protagonist to lose the beloved and pursue social recognition. Only at the narrative’s conclusion does the character realize the misalignment, understanding that the true “beloved” must be sought within the self rather than externally.

Similarly, in Dear Cousin is Lost (Dukhtar’dā’ī-i Gumshudah, 1998) the narrative uses illogical sequences and fragmented storytelling, where moments of silence, visual gaps, and disjointed interactions act as nodes that the audience mentally connects. These gaps—such as the drowned bride, the floating camera, and the interplay between the director, ‘Alī, and the unseen bride—require viewers to actively construct narrative meaning, linking metaphoric elements (water as loss, the camera as memory, the air as freedom) to produce a coherent internal Gestalt of the story. The juxtaposition of expected and unexpected events creates cognitive tension, and the audience completes the narrative using prior knowledge, intuition, and emotional inference.

In both films, silence function as a cognitive and semiotic tool, distinct from mere muteness or inaction. Deliberate silence—whether a pause in dialogue, an unshown event, or a gap in the visual field—evokes meanings that contribute directly to narrative construction. This aligns with the principle of closure: the human brain perceives incomplete visual or auditory information as part of a whole, filling gaps to form a coherent narrative experience. In these films, audiences mentally complete what is not explicitly presented, engaging actively in the interpretation of the narrative.

Thus, silence in cinema serves a dual purpose: aesthetically, it produces suspense, poetic resonance, and emotional engagement; cognitively, it mobilizes the audience’s perceptual and inferential capacities, allowing them to reconstruct hidden narrative elements. By strategically omitting key moments, both The Pear Tree and Dear Cousin is Lost exemplify how biologically grounded cognitive mechanisms—rooted in the principle of closure—underlie the reception of cinematic narratives, transforming what is absent into a site of meaning and interpretive participation.

Mihrjūyī’s filmmaking is often situated within the framework of the Iranian New Wave—a style that privileges visual composition, symbolism, and atmospherics over linear, plot-driven narratives. This style typically incorporates non-linear storytelling and focuses on philosophical reflection rather than delivering definitive resolutions. Such an approach resonates with the ideas of Viktor Shklovsky, who distinguishes poetic cinema from prosaic cinema, arguing that its primary concern is not narrative or conventional plot, but the formal construction of the film, which makes the audience perceive familiar objects and actions in new and heightened ways.33Viktor Shklovsky, “Poetry and Prose in Cinematography,” in Russian Formalist Criticism: Four Essays, ed. and trans. Lee T. Lemon and Marion J. Reis (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1965), 10–14. In his differentiation he identifies that cinema enables the viewer to encounter the world in a renewed way, moving beyond a merely linear reading of narrative. As he observes, through the concept of ostranenie (defamiliarization), cinema can “return sensation to our limbs,” allowing viewers to experience the world freshly and deepening their engagement with their surroundings.34Viktor Shklovsky, “Poetry and Prose in Cinematography,” in Russian Formalist Criticism: Four Essays, ed. and trans. Lee T. Lemon and Marion J. Reis (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1965), 11.

Building on this formalist foundation, contemporary cognitive theorists such as Daniel Stern expand on how viewers experience cinema on a pre-reflective, sensory level. Stern’s concept of “vitality affects” describes the dynamic, temporal qualities of perception—the sensory and affective impulses that arise before explicit narrative meaning is formed.35Daniel Stern, The Interpersonal World of the Infant: A View from Psychoanalysis and Developmental Psychology (New York: Basic Books, 1987), 45–48. In other words, the audience’s engagement with film can occur through rhythms, gestures, and audiovisual patterns, rather than solely through plot comprehension. By linking Shklovsky’s emphasis on formal perception to Stern’s cognitive framework, one can trace a continuum from early theories of poetic cinema to modern understandings of embodied cinematic experience. A significant portion of Mihrjūyī’s style—particularly in Dear Cousin is Lost—aligns with this perspective, as he abandons conventional storytelling to create a sensory and emotional experience. Through his use of surrealist style and cinematic silence as a narrative technique—both at the structural and semantic levels—Mihrjūyī compels the viewer to confront the dynamics of form rather than the conventions of classical narrative.

Extending this line of inquiry, Tom Gunning emphasizes that the essence of poetic cinema lies in its ability to estrange perception and reveal “new ways of sensing and knowing the world,” positioning form not as a vessel for meaning but as a site of aesthetic and cognitive renewal.36Tom Gunning, “The Question of Poetic Cinema,” in The Palgrave Handbook of the Philosophy of Film and Motion Pictures, ed. Noël Carroll, Thomas Nannicelli, and Piers Rawling (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), 551–71. Similarly, Maarten Coëgnarts and Peter Kravanja propose an embodied poetics of cinema, asserting that films communicate abstract meaning through patterns of perception and bodily experience shared across viewers. They focus on “image schemas,” such as SOURCE-PATH-GOAL and CENTRE-PERIPHERY, which structure how movement, spatial relations, and intensity are perceived, and show how these schemas can be metaphorically extended to represent time, emotion, and thought. By highlighting how rhythm, camera movement, and audiovisual patterns are experienced corporeally, their framework demonstrates that poetic cinema engages audiences pre-reflectively, eliciting sensory and affective responses that go beyond intellectual comprehension. In this way, their work extends Shklovsky’s ideas, illustrating how cinematic form can foster a participatory, embodied experience that transcends traditional narrative structures.37Maarten Coëgnarts and Peter Kravanja, “Towards an Embodied Poetics of Cinema: The Metaphoric Construction of Abstract Meaning in Film,” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media 4 (2012): 1–15.

Thus, Mihrjūyī’s films exemplify poetic cinema by deliberately challenging conventional narrative structures and engaging viewers on a pre-reflective, sensory level. In this style, silence becomes a central narrative device, creating a perceptual space that encourages introspection and embodied engagement. By minimizing explicit dialogue or linear exposition, the films cultivate an environment in which the audience interacts with audiovisual rhythms, gestures, and spatial patterns, activating what Daniel Stern terms “vitality affects”—dynamic, temporal qualities of perception that arise before conscious interpretation. Similarly, drawing on the framework of Coëgnarts and Kravanja, Mihrjūyī’s use of visual composition, camera movement, and silence can be seen as employing image schemas that metaphorically structure abstract concepts such as time, emotion, and relational dynamics. In this way, the viewer participates actively in meaning-making, experiencing the film not merely intellectually but in an embodied way, as form and sensation guide perception and interpretation. Silence, therefore, functions as both a cognitive and aesthetic tool: it opens a space for ambiguity, reflection, and personal resonance, heightening sensory awareness and inviting the audience into a participatory cinematic experience.

From a cognitive perspective, silence engages the brain’s predictive and inferential mechanisms: when information is missing, the mind actively fills in gaps, anticipates possible continuations, and constructs coherent interpretations based on prior knowledge and experience.38Leila Sadeghi, A Cognitive Approach to Literary Theory [Naqd-i adabī bā rūykard-i shinākhtī] vol. 3 (Tehran: Logos Publications, 2022), 215. This aligns with Gestalt principles of closure, where perception and understanding rely not only on what is present but also on the brain’s ability to infer and anticipate absent elements. As Barbara Johnstone suggests, silence only becomes legible when it is foregrounded against textual fragments, drawing attention to absence itself.39Barbara Johnstone, Discourse Analysis (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008), 70. In this way, discursive silence becomes a cognitive tool that fosters active engagement, imagination, and deeper comprehension of narrative structures.

These cognitive mechanisms provide a framework for analyzing how silence operates within cinematic narratives, guiding audience interpretation and shaping perceptual and emotional engagement. Drawing on Sadeghi’s typology (2009), this study distinguishes structural, semantic, and implicational forms of silence, each contributing uniquely to audience engagement and meaning-making.40Leila Sadeghi, “The Discursive Function of Silence in Short Stories [Kārkard-i guftimānī-i sukūt dar dāstān-i kūtāh]” (Master’s thesis, Allameh Tabatabaʾi University, 2009). By examining these dimensions in the two films, the research demonstrates how silence functions as a productive site for interpretation, enhancing narrative logic while activating viewers’ perceptual capacities. Through sensory and affective engagement, audiences reconstruct unstated events and link fragmented narrative elements, forming a participatory experience that connects individual perception with broader socio-cultural contexts. In this way, silence in Mihrjūyī’s cinema emerges as a defining feature of poetic cinema, creating layered spaces for reflection and offering novel means to convey the subtleties and complexities of human experience.

In sum, discursive silence can be understood as a cognitive phenomenon in which the absence of textual or auditory elements does not denote a deficit but instead functions as a generative gap that engages the mind’s predictive and inferential mechanisms. Rather than representing emptiness, silence operates at the intersection of narrative structure and cognitive processing: what is withheld prompts mental closure, encourages the anticipation of narrative continuations, and facilitates the reconstruction of meaning from incomplete information. Through this dynamic interaction, silence transforms absence into an active site of interpretation, shaping coherence and enriching narrative comprehension. Building on this perspective, discursive silence can be systematically categorized into three interrelated domains:41Leila Sadeghi, A Cognitive Approach to Literary Theory [Naqd-i adabī bā rūykard-i shinākhtī] vol. 3 (Tehran: Logos Publications, 2022), 216-227.

- Structural Silence — located at the level of textual or narrative organization.

- Omission: A silence produced by the physical absence of narrative segments. Certain elements are deliberately cut or left unexpressed, compelling the reader to supply them through the Gestalt principle of closure. In this case, meaning arises not from what is presented but from the recognition of a missing part that the mind reconstructs.

- Cataphora (Deferred Disclosure): A silence generated by deferred disclosure. Information is withheld at one point in the text and introduced later, requiring the reader to maintain a provisional representation and retrospectively integrate the missing detail once it appears. Cognitively, this engages memory and backtracking processes to restore coherence.

- Semantic Silence — arising from substitution or displacement of meaning.

- Metaphor: A silence that conceals one meaning beneath another by mapping an abstract concept onto a more concrete domain. The explicit expression displaces the underlying content, which the reader must reconstruct by identifying similarity across domains. This cognitive mechanism produces new interpretive possibilities by layering absence and presence.

- Metonymy: A silence that emerges when two entities share a conceptual domain or scope, and one is used to evoke the other. By presenting only part of a whole, or cause in place of effect, the narrative withholds direct articulation, relying on the reader’s associative cognition to retrieve the absent referent.

- Implicational Silence — grounded in Herbert Paul Grice’s cooperative principle, which holds that communication relies on shared expectations expressed through four maxims: quantity (provide the right amount of information), quality (speak truthfully), relation (be relevant), and manner (be clear and orderly).42Herbert Paul Grice, “Meaning,” Philosophical Review 66 (1957): 377–88. Silence in narrative emerges when these expectations are either upheld or strategically flouted, prompting the audience to supply meaning through cognitive processes such as schema activation, presupposition, and inference.

- Presupposition (as schemata): This type of silence depends on the audience’s prior knowledge, cultural frameworks, and mental schemas to interpret narrative gaps. Rather than violating conversational norms, presuppositional silence aligns with the Maxim of Quantity: only partial information is provided, requiring the audience to infer unstated elements. By activating shared assumptions and background knowledge, the narrative conveys meaning indirectly, embedding significance in the cognitive context rather than in explicit text.

- Implication (as inference): This form of silence prompts the audience to actively reconstruct meaning beyond what is directly presented. It engages cognitive processes to detect relevance and resolve ambiguity, corresponding to the Maxims of Relation and Manner: meaning is implied rather than stated explicitly. By encountering details that seem unrelated or incomplete, viewers or readers are compelled to draw connections, bridging gaps and elaborating on the narrative through inference. In this way, inferential silence transforms absence into a semiotic cue that guides interpretation.

|

Type of Silence |

Subcategory |

Role in Narrative and Meaning-Making |

|

Structural Silence |

Omission |

Leaves events, actions, or explanations unstated, creating gaps that compel viewers to actively reconstruct the narrative. |

|

Cataphora / Deferred Disclosure |

Delays revealing information, requiring the audience to maintain provisional understanding and integrate later details to make sense of the story. |

|

|

Semantic Silence |

Metonymy |

Objects, gestures, or minor details stand for broader concepts (e.g., the pear tree for lost love and blocked creativity). |

|

Metaphor |

Concrete images symbolize abstract ideas, evoking emotional or conceptual meaning indirectly. |

|

|

Implicational Silence |

Presuppositional |

Relies on audience’s prior knowledge and cultural schemas to interpret narrative gaps (relates to Maxim of Quantity: only partial info given, requiring inference). |

|

Inferential |

Encourages viewers to draw connections and reconstruct meaning beyond what is shown (relates to Maxims of Relation and Manner: relevance and clarity are implied, not explicit). |

Table 1: Typology of Discursive Silence and Their Functions in Meaning-Making (adapted from Sadeghi, 2009)

This tripartite model highlights that discursive silence is not reducible to muteness or textual voids. Rather, it functions as a cognitive strategy of absence, systematically embedded within narrative structures, semantic substitutions, and implicational cues. Each type of silence mobilizes distinct mental processes—closure, analogy, association, schemata, and inference—demonstrating how meaning emerges as much from what is withheld as from what is articulated.

The Pear Tree (1998): A Meditation on Time and Lost Love

Mahmūd, a writer struggling to finish his latest book, retreats to his family’s orchard in Damavand. There, the old pear tree, full of childhood memories, remains barren, and Mahmūd is asked to participate in a ritual to revive it. During his stay, he recalls his adolescence, when he fell in love with his cousin “Mīm”, who reciprocated his affection. Years later, after becoming involved in political activities, he fails to respond to her letters and eventually learns of her death while he was in prison. Now approaching sixty, Mahmūd remains creatively and emotionally stagnant, like the barren pear tree of his youth.

Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī’s The Pear Tree is a meditation on love, memory, and the passage of time, tracing the reflective journey of its protagonist, Mahmūd, as he revisits his past and confronts the emotional impact of lost affection and interrupted creativity. The film intricately interweaves past and present, employing silence not merely as a formal pause but as a deliberate cognitive and narrative device that engages the viewer in constructing meaning. Following the tripartite model of discursive silence, silence in The Pear Tree operates across structural, semantic, and implicational dimensions, guiding inference, interpretation, and participation.

Mahmūd’s fragmented recollections, the episodic non-linear narrative, and recurring visual motifs—such as the pear tree and the spider web—create deliberate gaps in the story. These absences invite the audience to engage in Gestalt closure, mentally filling in missing elements to construct a coherent understanding of Mahmūd’s life, relationships, and emotional state. Deferred revelations, such as memories that emerge later in the narrative, require viewers to maintain provisional representations and retrospectively integrate new details, activating memory and backtracking processes to restore coherence.

Building on these structural gaps, the pear tree itself operates as a metaphorical conduit for time, lost love, and creative inspiration, displacing explicit exposition and prompting viewers to reconstruct underlying meanings through analogy. Other objects and visual motifs function metonymically: a spider web, a neglected manuscript, or a childhood photograph evokes broader concepts—entanglement, interrupted creativity, past intimacy—without directly articulating them. These semantic substitutions stimulate associative cognition, encouraging viewers to infer connections between what is visible and what is absent.

Extending from both structural and semantic silences, the film strategically introduces details that appear disconnected or irrelevant, such as Mahmūd’s absorption in writing while the gardener announces the pear tree. These moments create processing gaps that engage the audience in inferential elaboration. Viewers instinctively seek coherence, drawing on contextual cues, mental schemas, and prior knowledge to bridge these gaps. In doing so, absence becomes meaningful, transforming what is unsaid or unseen into a space of active interpretation and narrative participation.

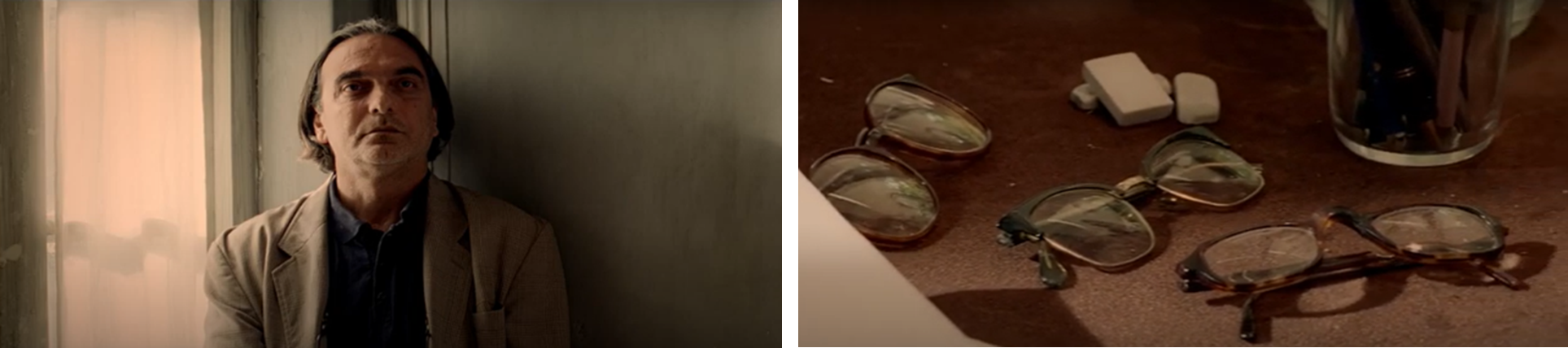

From the opening sequences, the film establishes a rhythm of structural silence through omission and evocation. Mahmūd’s interactions with his surroundings, punctuated by silences and visual ellipses, draw immediate attention to what is unsaid or unseen. For instance, the sequence at 00:03:23 presents the gardener knocking on the window to inform Mahmūd about the pear tree, while Mahmūd remains absorbed in his writing (Figure 2-1). The narrative then cuts from Mahmūd’s distracted wandering at 00:04:21 to a medium shot of his cluttered desk, littered with glasses, erasers, cups, cigarette packs, and typewriters.

Figure 2-1: A medium shot of the gardener standing silently behind the window, framed by reflections of the garden, while Mahmūd sits inside absorbed in his thoughts. Still from The Pear Tree (Dirakht-i Gulābī), directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī, 1998 (00:03:23).

This abrupt transition, lacking explicit explanation, generates a cognitive gap characteristic of structural silence: the audience must mentally connect Mahmūd’s distraction, his writing attempts, and the gardener’s intervention. The omission of direct continuity engages the viewer in Gestalt closure, requiring them to reconstruct the temporal and spatial links and thus actively participate in the narrative. Simultaneously, these silences carry semantic weight: the cluttered desk and Mahmūd’s absorption function metonymically, evoking his disorganization, creative struggles, and emotional detachment without directly stating them. By withholding explicit exposition, the film transforms absence into meaning, illustrating how structural and semantic silences collaborate to engage the audience in interpretive reconstruction.

Figure 2-2: Mahmūd’s distracted wandering around the room (00:04:21) transitions to a shot of his cluttered desk (00:07:46), scattered with three pairs of glasses, erasers, cups, cigarette packs, and typewriters. Stills from The Pear Tree (Dirakht-i Gulābī), directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī, 1998.

Similarly, Mahmūd enumerates the potential productivity of his writing:

If I write one page an hour, and ten hours a day, that’s ten pages a day, seventy pages a week, and by the first day of winter, nearly a thousand pages. The hardcover would be ready, embossed with gold letters, and would amount to four volumes.43The Pear Tree, directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī (Iran: Fārābī Cinema Foundation, 1998), 00:06:05.

Yet the film visually depicts him staring blankly, refraining from writing. At this moment, Mahmūd is immobilized, while the gardener, having opened the door, says, “Sir, go take a look at the pear tree.” Mahmūd mutters in frustration, “To hell with the pear tree, with trees and plants. Leave me alone,” and steps onto the balcony.44The Pear Tree, directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī (Iran: Fārābī Cinema Foundation, 1998), 00.06.59. The temporal leap and lack of explicit linkage between Mahmūd’s inner calculation, his inaction, and the gardener’s intervention constitute an instance of structural silence: the audience must bridge the narrative gap and mentally reconstruct the continuity between intention, action, and external stimuli.

At the same time, this scene embodies semantic silence. The juxtaposition of Mahmūd’s obsessive internal focus with the external significance of the pear tree conveys meaning indirectly: the unshown tree, Mahmūd’s blank stare, and his frustrated mutterings invite the audience to infer his creative and emotional stagnation. These metonymic and metaphorical cues allow the viewer to map abstract concepts—productive ambition, distraction, frustration—onto concrete visual elements, generating interpretive depth without explicit exposition.

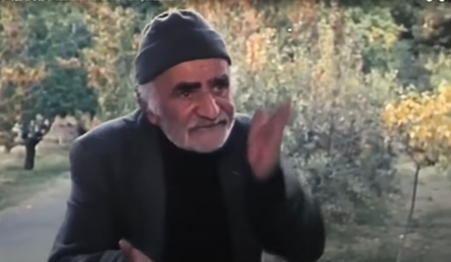

Figure 2-3: The gardener expresses his frustration at the pear tree’s lack of fruit, gesturing and speaking aloud while the tree itself remains off-screen. Still from The Pear Tree (Dirakht-i Gulābī), directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī, 1998 (00:12:37).

The gardener’s vocalization of frustration—describing the tree’s lack of fruit as “an unforgiving impoliteness” and speculating about magic, illness, or bewitchment—further illustrates omission as structural silence.45The Pear Tree, directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī (Iran: Fārābī Cinema Foundation, 1998), 00:13:21. The tree itself remains absent from the frame, and the visual and narrative gap forces the audience to infer its presence, significance, and symbolic weight. The deliberate cuts and temporal progression emphasize the gardener’s obsessive care—watering, pruning, fertilizing, speaking lovingly—and highlight the contrast between human effort and the tree’s muteness. Here, silence becomes a generative space: viewers mentally reconstruct the interplay of care, expectation, and futility, implicitly linking the tree’s fruitlessness to Mahmūd’s creative and emotional sterility.

Beyond its structural absence, this sequence also evokes semantic and implicational forms of silence. Semantically, the gardener’s lamentations— “I’ve caressed it and expressed love to it… but it was all useless” —do not offer a literal explanation for the tree’s fruitlessness. Instead, meaning arises through metaphor and metonymy: the pear tree functions metaphorically as a stand-in for human barrenness, reflecting the futility of both the gardener’s devotion and Mahmūd’s blocked creativity. At the same time, the gardener’s physical acts—watering, pruning, caressing—operate metonymically, signifying care, persistence, and ritual devotion, which contrast sharply with the tree’s muteness.

Through this interplay, the narrative demonstrates how semantic silence transforms absence into meaning. The tree’s fruitlessness is not explicitly explained; rather, its significance is implied through metaphorical and metonymic relationships, requiring the audience to infer connections between action, object, and abstract concepts. In this way, the film leverages silence as a cognitive and interpretive tool: meaning emerges from what is withheld and displaced, inviting viewers to actively reconstruct both the symbolic and emotional dimensions of the scene.

On the level of presupposition, the gardener’s detailed account of his labor—watering, pruning, fertilizing, and speaking words of love—relies on a shared cultural schema: diligent care is expected to yield growth and fruit. This background knowledge shapes the audience’s understanding of the tree as an object that should respond to human effort, rendering its barrenness uncanny and unjust. On the level of inference, the gardener’s remark, “There’s nothing wrong with him,” creates a deliberate gap that demands interpretive reasoning. With no external cause offered for the tree’s silence, viewers are compelled to bridge the absence by mapping the tree’s muteness onto Mahmūd’s creative and emotional sterility.

In this way, the silence between the gardener’s words and the missing answer becomes productive, guiding the audience to construct meaning beyond what is explicitly stated. Through these mechanisms, implicational silence transforms the pear tree into a site where presupposed expectations collapse and new inferences must be generated, actively engaging viewers in reconstructing the narrative’s unspoken connections. Moreover, this sequence exemplifies a Relation violation: details that appear disconnected—the gardener’s dialogue, Mahmūd’s internal preoccupations, and the unseen tree—prompt the audience to search for hidden links, turning absence into a cognitive and interpretive space.

In a childhood memory, Mahmūd recalls an incident in which the gardener tricks him into climbing a tree, only to deceive him when promising a donkey ride: “You used to like all the trees here before. I remember one day you went to the well with Ms. Mīmchah on the donkey.”46The Pear Tree, directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī (Iran: Fārābī Cinema Foundation, 1998), 00:16:30. Mahmūd sees himself sitting atop a massive tree, and despite repeated calls, he does not respond, enjoying the concern of the adults. Shukrallāh, the gardener—“the gardener of Damāvand Garden… and he was the sole ruler of all the trees in the village”—is the only one who knows where he is hiding.47The Pear Tree, directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī (Iran: Fārābī Cinema Foundation, 1998), 00:19:41–00:19:52. This episode exemplifies structural silence: Mahmūd’s non-response and the absence of direct dialogue between him and the other adults create a cognitive gap that requires viewers to infer his motives, agency, and emotional negotiation with authority. His defiance signals both a disconnect from the adult world and the early formation of his artistic self, asserting autonomy from imposed structures. When he finally descends and realizes he has been deceived, the structural gaps amplify the emotional weight of disillusionment and self-awareness.

This memory also engages semantic silence. Mahmūd’s refusal to answer, his silent enjoyment of attention, and the discrepancy between expectation and outcome function metaphorically: the tree becomes a site of autonomy, risk, and emerging identity, while his concealment signals early creative self-fashioning. The narrative displaces explicit explanation, requiring the audience to reconstruct the psychological stakes through his actions and the surrounding context.

Finally, Mahmūd’s recollection conveys the intensity of youthful passion and internal disorientation:

I’m twelve years old and I’m in love twelve thousand times more than the capacity of my small heart and soul… I’m confused and out of it, I’m dry. I’m a mess and mesmerized.48The Pear Tree, directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī (Iran: Fārābī Cinema Foundation, 1998), 00:22:24.

Semantically, the narrative does not explicitly describe his emotional turbulence; instead, meaning emerges through his fragmented, overflowing expressions of love and confusion, which function metaphorically to signal the immensity and chaos of his inner life. On an implicational level, the gaps in articulation invite the audience to engage in inferential reasoning, reconstructing the depth of his early attachments and the ways these intense feelings shape his emerging identity. The unspoken tension—between the vastness of his emotions and his inability to fully articulate or control them—creates a reflective cognitive space where viewers mentally assemble the psychological and artistic stakes of his childhood. In this way, Mihrjūyī demonstrates how inferential silence can render internal states vividly, showing that what is left unsaid can be as telling as any spoken dialogue in conveying formative emotional and creative development.

Rapid leaps between self-observation (“I’m not myself, my usual self. Even better!”), bodily awareness (“I’m ugly, tall, and disproportionate… although my legs have suddenly and frighteningly grown.”), aspirational statements (“I want to become an author… to be faithful, forever, to my great and eternal love, ‘M’.”), and temporal wishes (“I wish I were twelve years old again… Even the dead ones I wish”) leave gaps in narrative continuity. These disjunctions compel the audience to mentally reconstruct connections between Mahmūd’s internal states and external events, actively bridging the discontinuities created by the narrative form.

Figure 2-4: Mahmūd as a child standing next to Mīm, with the pear tree visible in the background. Still from The Pear Tree (Dirakht-i Gulābī), directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī, 1998, (00:23:55).

Concrete objects and sensory details evoke abstract ideas: the reference to M’s tennis shoes49The Pear Tree, directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī (Iran: Fārābī Cinema Foundation, 1998), 00:24:47. functions metonymically, standing for her presence, intimacy, and the emotional significance of lost love. Bodily descriptions, such as his sudden physical growth, metaphorically reflect the anxiety and disorientation of adolescence. Likewise, Mahmūd’s wishes to accelerate or slow time metaphorically encode his impatience for maturity and his ambivalence toward the passage of life. By displacing meaning into objects, sensations, and imaginative projection, the narrative withholds explicit explanation, requiring the audience to infer his emotional and developmental stakes.

Presupposition relies on cultural and emotional schemas: viewers understand the norms of childhood love, youthful aspiration, and self-consciousness, which Mahmūd assumes without explicitly stating. Inferential silence arises as the audience interprets gaps, such as the impossibility of revisiting his youth or reconnecting with “M,” and maps these absences onto his emerging identity and creative ambition. The sequence also creates a Relation violation: adult instructions about hygiene, appearance, and conduct50The Pear Tree, directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī (Iran: Fārābī Cinema Foundation, 1998), 00:25:46. appear disconnected from Mahmūd’s intense interiority, prompting the audience to reconcile these seemingly irrelevant elements with his psychological and emotional experience.

Figure 2-5: A sudden cut to a past scene, depicts the narrator being taken to prison. Still from The Pear Tree (Dirakht-i Gulābī), directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī, 1998 (01:18:48).

The narrator reflects, “I had built a world of bubbles… which was popped with a snap of the fingers.”51The Pear Tree, directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī (Iran: Fārābī Cinema Foundation, 1998), 01:18:48. Structurally, this moment creates a deliberate discontinuity: the film immediately leaps to a past trauma—his imprisonment two years before the revolution—without a narrative bridge linking personal loss and political suffering. This structural silence compels the audience to mentally connect the rupture between Mahmūd’s private heartbreak over “M” and the political consequences of his beliefs, reconstructing the trajectory from youthful romantic desire to disillusioned political prisoner.

The disjointedness continues when the playful, fragmented dialogue of children in the garden—“Had you told us that judging you would be something dangerous to us?”—unfolds amidst their games near the pear tree.52The Pear Tree, directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī (Iran: Fārābī Cinema Foundation, 1998), 01:21:43. Here, structural silence is reinforced by tonal shifts between teasing, laughter, and serious questioning, leaving viewers to navigate the gap between surface play and the underlying emotional and relational stakes.

Visually present, the pear tree functions metaphorically as a symbol of Mahmūd’s later creative and emotional barrenness, while its unspoken significance relies on the audience’s ability to infer meaning from the interplay of dialogue, gesture, and setting. In fact, viewers must engage in inferential reasoning, bridging the absence of explicit commentary to understand the symbolic resonance of the tree and its relation to Mahmūd’s internal and external experiences. Through these mechanisms, silence transforms discontinuity into a site for cognitive and interpretive engagement, demonstrating how Mihrjūyī relies on what is withheld to generate narrative depth.

Mahmūd, in a reflective moment, recalls his love for “M” and contrasts it with his devotion to his work.53The Pear Tree, directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī (Iran: Fārābī Cinema Foundation, 1998), 00:38:45. The metaphor “Love is Career” encapsulates the emotional substitution that has reshaped the course of his life: love, once vibrant and deeply felt, has been displaced by professional ambition and the performative responsibilities of the intellectual class. This semantic silence, implied rather than articulated, resonates throughout his fragmented memories, allowing the audience to infer the costs of societal expectation and the internalized prioritization of achievement over intimacy. The scene links seamlessly to the previous childhood sequences: just as the garden games and the echo of Joan of Arc invite inferential reconstruction, Mahmūd’s conflation of love with career activates interpretive schemata, prompting the audience to map personal, emotional, and social pressures onto his trajectory. Together, these layers compel the viewer into active interpretation, bridging childhood play, adult imprisonment, and personal and ideological transformation. Silence here is not emptiness; it is a cognitive space where the audience must infer connections, reconcile discontinuities, and map Mahmūd’s internal conflicts onto symbolic frameworks, generating a reflective meditation on lost love, thwarted creativity, and moral endurance.

Figure 2-6: A childhood scene in the garden where “M” is play-acts as Joan of Arc, surrounded by children who pretend to burn her in playful imitation of martyrdom. Still from The Pear Tree (Dirakht-i Gulābī), directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī, 1998 (01:22:25).

Inferential silence dominates the scene,54The Pear Tree, directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī (Iran: Fārābī Cinema Foundation, 1998), 01:22:25. as the narrator’s fragmented questioning —“Had you told us that judging you would be something dangerous to us?”— and cryptic remarks about martyrdom prompt the audience to activate cognitive schemas grounded in cultural knowledge. On an implicational level, viewers rely on shared assumptions about authority, obedience, and suffering, while the echo of Joan of Arc provides a latent schema for courage, sacrifice, and moral trial. In Mahmūd’s childhood memory, “M” is positioned close to the pear tree while the other children pretend to “fire” her in their game, reinforcing her symbolic role as a Joan of Arc figure. This presuppositional framework aligns with the maxim of Quantity, as not every connection between the game, M’s heroic symbolism, and Mahmūd’s developing understanding is explicitly stated, and the maxim of Manner, since the fragmented and playful presentation invites the audience to interpret meaning through context. By linking “M,” the pear tree, and the children’s actions, the scene encourages viewers to infer both the stakes of the game and its deeper symbolic resonance, connecting Mahmūd’s personal experience to archetypes of courage, moral trial, and early imaginative formation.

At the semantic level, the statement “Martyrdom is the torture we go through in the prison… Could there be a worse pain than this?” transforms the courtroom—and, in childhood echoes, the garden games—into metonyms for systemic constraint and moral trial. Simultaneously, the pear tree’s persistent fruitlessness and the gardener’s lamentations function metaphorically, representing Mahmūd’s creative and emotional barrenness. Meaning emerges not through direct exposition but via these displaced and layered cues, inviting viewers to reconstruct conceptual and emotional connections.

At 01:12:33, Mahmūd’s reflection on the eternal yet lost “M” illustrates how affection evolves into broader commitment: the love that once animated his heart is redirected toward revolutionary ideals, opposition to oppressive powers, and dutiful engagement with party commands. This shift is presented without explicit narrative explanation, creating inferential silence. The audience infers the causal relationship between absence of “M,” unanswered letters, and Mahmūd’s immersion in political work. This process engages schemas, as the audience relies on prior knowledge and conceptual frameworks to fill in unstated causal links between personal desire and political engagement. Viewers infer that Mahmūd’s intimate longing for “M,” left unresolved, shapes his ideological commitments. In doing so, the narrative invokes the maxim of Quantity, by leaving certain connections unsaid, and the maxim of Manner, by presenting these relationships elliptically, requiring the audience to actively integrate context, memory, and cultural understanding to reconstruct meaning.

Further gaps—such as Mahmūd’s acknowledgment of poverty, illness, and threats against him,55The Pear Tree, directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī (Iran: Fārābī Cinema Foundation, 1998), 01:13:20. illustrate structural silence. The omission of explicit contextual detail compels the audience to reconstruct the conditions of his struggle, mentally filling in the narrative gaps. His declaration, “I know they’re after me, but I don’t care, I’m in love,”56The Pear Tree, directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī (Iran: Fārābī Cinema Foundation, 1998), 01:13:26. signals a continuity of devotion that has shifted from personal to ideological commitment. Semantic silence emerges in Mahmūd’s reflections on life’s excitement, missed opportunities with “M,” and his literary ambitions.57The Pear Tree, directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī (Iran: Fārābī Cinema Foundation, 1998), 01:13:38. Here, concrete objects and acts—unfulfilled correspondence, unaddressed letters, and the “best and most complete book” he writes despite doubts—function metonymically, standing for redirected ambition and compromised emotional fulfillment. Broader reflections on his emotional state operate metaphorically, substituting direct exposition with abstract, conceptual meaning.

The absent figure of “M” continues to generate multiple forms of silence. Though she never appears physically, recurring references—“Did you really have feelings for ‘M’?”58The Pear Tree, directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī (Iran: Fārābī Cinema Foundation, 1998), 01:24:44. and “She was a goner herself”59The Pear Tree, directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī (Iran: Fārābī Cinema Foundation, 1998), 01:24:50.—position her as a conceptual presence, whose significance transcends literal depiction. Semantically, her love transforms into ideological and performative commitment, dispersing into revolutionary zeal—posting images of Marx and Lenin, chanting slogans, and participating alongside comrades—mirroring Mahmūd’s adult responsibilities and creative labor. Implication (as inferential silence) emerges as the audience bridges the gaps through presupposed schemas of lost love, personal transformation, and redirected devotion, reconstructing the causal and emotional links between absence of “M” and Mahmūd’s ideological engagement. This silence is reinforced visually: when the gardener curses the pear tree, the cut to Mahmūd’s image extends the metaphor, implying that he, like the tree, bears the weight of frustration, expectation, and stifled potential.

I am still in love, and this love and heart-throb has taken a new direction. This is a new and truthful love, one that is more worldly. The eternal “M,” the lost “M,” now appears on a larger scale. “M”’s love within me has transformed into hatred and disdain toward the British and the dictatorial class. “M”’s letters went unanswered, but that no longer matters; her presence has become integrated into the political ideals of the party.60The Pear Tree, directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī (Iran: Fārābī Cinema Foundation, 1998), 01.12.18.

This scene exemplifies implicational silence, where the shift from personal to ideological attachment is inferred rather than explicitly narrated, engaging the audience in reconstructing the psychological and emotional trajectory. The narrator observes:

All but the pear tree… With a dead body and empty hands… is standing in the middle of all that commotion and doesn’t care about all that complaint… Like an old sheikh sitting in the quiet… Down to the earth… Patient… And thankful.61The Pear Tree, directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī (Iran: Fārābī Cinema Foundation, 1998), 01:26:50.

The tree’s stillness and apparent indifference function as semantic silence, a metaphorical substitution for Mahmūd’s creative and emotional barrenness. Its absence of fruit and activity conveys meaning more powerfully than direct exposition. Sensory layering—the aromas of the tree, memories of M’s tennis shoes, and tactile engagement with the fruit,62The Pear Tree, directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī (Iran: Fārābī Cinema Foundation, 1998), 01:29:57. acts metonymically, signaling the narrator’s internal stasis and mnemonic associations. Semantic silence thus invites the audience to infer significance without explicit narrative commentary, exemplifying Mihrjūyī’s sophisticated layering of structural, semantic, and implicational silences.

At 01:27:13, the staged “execution” of the pear tree exemplifies layered silence that engages the audience cognitively and emotionally. Structurally, the sequence withholds the actual consequences of the gardener’s threat—“Tree, you have behaved against the laws of the garden and you deserve to die”—creating a discontinuity that compels viewers to anticipate outcomes. The tree functions metaphorically for Mahmūd, its threatened destruction paralleling his creative and emotional sterility, while its stillness under judgment conveys the weight of internalized responsibility. When the village head intervenes—“You must issue the judgment”—authority is juxtaposed with the act, shifting moral accountability onto Mahmūd and highlighting social and ethical pressures. Implicationally, viewers rely on presuppositional schemas, drawing on prior knowledge and cultural understanding (including the Joan of Arc imagery from earlier childhood play), to infer Mahmūd’s internal struggle and the tension between duty, compulsion, and moral constraint. Through this interplay, silence operates as a generator of meaning: the gaps in action, the metaphorical substitution of tree for self, and reliance on cognitive schemas invite active interpretation of emotional, ethical, and creative stakes. The pear tree thus transforms from a passive symbol into a dynamic site of judgment and reflection, linking narrative absence to cognitive engagement.

Later, Mahmūd reflects on the passage of time and his suspended creativity, highlighting the enduring presence of inferential silence in his inner life: “It feels like I am sitting in an empty pause between two noisy minutes, between infinite past and infinite future.”63The Pear Tree, directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī (Iran: Fārābī Cinema Foundation, 1998), 00:21:36. Structurally, this moment creates a visual and temporal gap, as his gaze drifts away from objects, gardens, and gardeners—and from his “enlightened intellectual artist self”—without explicit narrative guidance, compelling the audience to dwell on the pause and reconstruct its significance. He focuses on a spider weaving its web: “Can’t you see the magnificent web it has woven? … I can’t see anything. That’s because you’re blind, deaf and dumb. You are selfish.”64The Pear Tree, directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī (Iran: Fārābī Cinema Foundation, 1998), 00:21:44. Semantically, Mahmūd’s attention to the spider, paired with the girl’s critical observation, functions as a metonym for disciplined, patient, and humble creative labor, contrasting with his own self-absorption. Implicationally, viewers engage presuppositional and inferential reasoning, mapping Mahmūd’s suspended creativity and reflective stasis onto the spider’s meticulous activity, thereby interpreting his longing for discipline, patience, and attentiveness without explicit exposition. In this way, the scene layers structural, semantic, and implicational silences, transforming visual and temporal absence into a cognitive and emotional site of reflection.

This meditation returns later at 01:33:32, when the spider weaving its web functions as both a structural and implicational mirror of the narrator’s state: structurally, the scene presents a visual pause with no dialogue, minimal movement beyond the spider’s meticulous weaving, and no explicit narrative guidance, producing a temporal and visual gap that compels the audience to dwell on the image and construct its meaning; implicationally, viewers are invited to infer through presupposition and cognitive mapping that Mahmūd’s suspended creativity and contemplative stasis are mirrored in the spider’s productive yet constrained activity, a careful construction that resonates with his emotional and creative blockage while allowing symbolic connections to emerge without explicit exposition. Taken together with the pear tree’s quiet presence and the absence of “M,” the spider becomes a site where Mihrjūyī layers structural, semantic, and implicational silences, transforming visual and temporal gaps into moments of cognitive and emotional reflection that link patient observation, blocked creativity, and symbolic absence into a cohesive meditation on longing, failure, and interpretive engagement.

Figure 2-7: Mahmūd sitting under the pear tree in his adolescence, reflecting on the significance of the tree. Still from The Pear Tree (Dirakht-i Gulābī), directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī, 1998 (01:32:42).

Semantic silence emerges through the contrast between Mahmūd’s internalized ideals and the spider’s quiet, persistent labor. He recalls his youthful declarations: “I feel very, very happy I’ve made a great decision. I want to become an author… or perhaps a poet… and I have sworn to be faithful to my great and eternal love, ‘M,’ forever.”65The Pear Tree, directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī (Iran: Fārābī Cinema Foundation, 1998), 00:23:15–00:23:22. These statements are grandiose and emotionally charged but undercut by hesitation and unspoken limitations. The phrase “or perhaps a poet” signals both ambition and doubt, leaving the source of that ambivalence unstated and inviting the audience to infer the intimidating weight of poetic creation. Similarly, his vow of eternal fidelity to “M” conveys youthful idealization and emotional intensity, yet the semantic silence resides in what is left unsaid: the practical impossibility, immaturity, and futility of such a promise.

The spider’s humble, careful weaving functions as a semantic substitution, signaling that authentic creativity requires patience, attention, and subtlety, in contrast to Mahmūd’s performative declarations. The unspoken tension between Mahmūd’s ego-driven self-perception and the spider’s modest productivity conveys meaning more powerfully than explicit exposition: the audience is prompted to infer that authenticity in art and life is less about grand statements and more about sustained, humble attention to one’s work. Finally, his lines — “I wish I could grow up faster. I wish time wasn’t so slow” — introduce temporal and existential tension, reflecting Mahmūd’s stalled agency and the structural and implicational silence of his awareness of past failure and unfulfilled potential.

Implicational silence emerges as viewers reconstruct Mahmūd’s psychological state. The spider mirrors his suspended creativity and unresolved desires: meticulous yet constrained, its activity parallels his stalled artistic growth and the impracticality of his youthful vows to “M.” The unspoken disillusionment—the recognition that phrases like “maybe even a poet” mask doubt and fear, and that eternal fidelity was an idealized, perhaps impossible promise,66The Pear Tree, directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī (Iran: Fārābī Cinema Foundation, 1998), 00:23:22–00:23:28. invites the audience to infer the tension between aspiration and reality. The girl’s remark that the spider is “more poet than you” intensifies this implicational silence, highlighting the contrast between Mahmūd’s performative self-image and the quiet efficacy of genuine effort. Through these cues, viewers actively infer his awareness of missed opportunities, personal inadequacy, and the gap between youthful idealism and lived experience, making silence a semiotic tool for cognitive and emotional engagement.

I feel very, very happy I’ve made a great decision. I want to become an author—or perhaps a poet. I have also sworn to be faithful to my great and eternal love, “M,” forever, or at least for as long as I’m alive. I only wish that time wouldn’t go by so slowly and turtle-like, and that it wasn’t stalling so much. I wish I’d turn 20, 30, or 40 quickly. I wish I’d be as old as mature, wise, and reputable men. How stupid I was.

Through the interplay of structural, semantic, and implicational silences, the spider scene crystallizes a meditation on creativity, humility, and the maturation from youthful ambition to reflective understanding. Structurally, the visual pause—with minimal movement and no dialogue—creates temporal and narrative gaps that compel the audience to dwell on the image and construct meaning. Semantically, the spider’s meticulous weaving substitutes for Mahmūd’s performative declarations, signaling that authentic creativity demands patience, attention, and subtlety. Implicationally, viewers infer his stalled growth, unrealized aspirations, and the contrast between youthful idealism and lived experience. By linking Mahmūd’s reflections to the spider’s silent, persistent labor, the film extends its motifs—the pear tree, “M”’s absence—demonstrating that disciplined observation and effort constitute meaningful engagement, in contrast to grandiose but hollow declarations. Mahmūd’s contemplation transforms the visual pause into a reflective cognitive space, inviting the audience to reconstruct the emotional, moral, and artistic stakes of his inner life.

Dear Cousin is Lost (1998): Silence, and the Narrative of Disorientation

Dear Cousin is Lost (Dukhtar’dā’ī-i Gumshudah), an episode of the Island Stories (Dāstān-hā-yi Jazīrah) series, follows a young girl who disappears while at the sea. Sometime later, she returns, flying through the clouds with two white wings. Her cousin, a young actor, believes in her miraculous return and even joins her in flight. Although the group around them is concerned, the cousin ultimately returns safely to the ground.

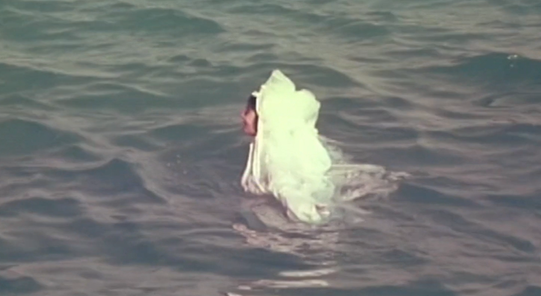

Dear Cousin is Lost continues Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī’s trajectory toward poetic cinema, offering a metafictional and surreal experience in which boundaries between reality, imagination, and the filmmaking process are constantly blurred. The narrative opens with a tragic event—the drowning of the bride (the cousin)—yet the story does not follow a conventional linear cause-and-effect trajectory. Instead, structural silences emerge through fragmented sequences, temporal leaps, and abrupt cuts, compelling the audience to mentally reconstruct connections and infer narrative continuity. Semantic silence operates as locations, objects, and cinematic gestures—such as the golden sunsets, dusty streets, or fleeting glimpses of characters—substitute for explicit exposition, inviting viewers to interpret emotional, cultural, and symbolic resonances. Implicational silence arises as the audience actively bridges gaps, connecting the filmmaking process itself to the narrative of loss and disorientation, and inferring meaning from the interplay of dreamlike sequences and self-referential storytelling. Kīsh Island, thus, functions not merely as a geographical backdrop but as a stage where absence, ambiguity, and layered silences guide cognitive and emotional engagement, producing a participatory cinematic experience.

Figure 3-1: The film opens with the haunting image of the bride (the cousin) drowning. Still from Dear Cousin is Lost (Dukhtar’dā’ī-i Gumshudah), directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī, 1998 (00:05:37).

In Dear Cousin is Lost, silence functions as a multifaceted narrative device that establishes surrealism and disorientation from the very opening sequence. The drowning of the bride exemplifies structural silence: she is first shown laughing and swimming, a lighthearted presence sharply contrasted with her sudden disappearance beneath the water, yet the causal link between play and tragedy is withheld. This omission and deferred disclosure compel the audience to mentally reconstruct the transition, generating a suspension of meaning and an active engagement with the narrative gap. Semantic silence emerges as the bride’s ethereal narration — “I am no longer who I used to be. I am something suspended, caught between my dreams” — maps abstract concepts of liminality, transformation, and emotional displacement onto the concrete imagery of swimming and disappearing, inviting viewers to infer psychological and symbolic significance beyond literal events. Metonymy is also at work: the sound of her “light steps” and the golden palm trees evoke her prior vitality and presence, standing in for the full scope of her character and the relational loss ‘Alī experiences. Simultaneously, the audience draws on cultural schemas about grief, danger, and the fragility of life to interpret ‘Alī’s frantic pursuit and the juxtaposition of the director and crew’s casual activity, bridging the gap between narrative expectation and cinematic reality. Inferential silence also functions cognitively, creating tension between the audience’s mental models and the film’s surreal logic. Environmental cues, such as sudden wind, chaotic crowds, or floating objects, generate implicit expectations of normality that are systematically undermined, producing cognitive estrangement and prompting the viewer to negotiate meaning actively. The interplay of these silences—the structural gaps, metaphorical layers, and inferred emotional stakes—positions the audience as an active co-creator of meaning, transforming the abrupt rupture from laughter to tragedy into a reflective meditation on loss, impermanence, and the unstable boundary between dream and reality.

A key example occurs with the bride’s sudden drowning. The cause is never explained, leaving a narrative void that would normally be completed by causal inference. Instead, the audience is presented with a discontinuity: ‘Alī’s frantic pursuit, the intervening crew, and environmental distractions. Conventional knowledge about narrative causality is insufficient; viewers must reconcile these disjointed elements to construct meaning, often blending the fantastical with the real. Similarly, ‘Alī’s apparent death and subsequent “resurrection” defy realist logic, compelling viewers to accept a poetic, dreamlike logic as the governing principle.

Implicit silence also functions cognitively, as it creates a tension between the audience’s mental models and the text’s surreal logic. The film deliberately positions presupposed knowledge against contradictory developments. For instance, environmental cues, such as sudden wind, chaotic crowds, or floating objects, generate implicit expectations of normality that are systematically undermined. This contrapuntal use of Inferential silence transforms audience assumptions into a tool for engaging with a new, internally consistent cinematic logic. The viewer experiences a form of cognitive estrangement, where prior schemas are suspended or inverted, prompting novel interpretations.

Figure 3-2: ‘Alī shouts and searches for the bride after her drowning. Still from Dear Cousin is Lost (Dukhtar’dā’ī-i Gumshudah), directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī, 1998 (00:05:45).

Furthermore, the sudden jump to behind-the-scenes sequences with the film crew, while ‘Alī’s main narrative continues, represents a key instance of structural silence. These interruptions disrupt the story’s flow and introduce a metafictional layer, blurring the boundary between reality and film production. The presence of the director, cameraman, and extras interacting playfully with ‘Alī reveals unseen processes behind narrative construction, such as planning, framing, and directing actions, without explicitly showing the full apparatus. This omission creates a structural gap that compels the audience to mentally reconstruct how the scene is shaped, bridging ‘Alī’s diegetic experience with the production context. Simultaneously, the camera, the director’s instructions, and the extras’ reactions function both metonymically and metaphorically, standing in for the entire filmmaking process, and representing broader themes of observation, mediation, and the artificiality of storytelling. By exposing only fragments of these processes, the film transforms absence into meaning, prompting viewers to actively infer the interplay between performance, direction, and narrative construction, and to understand how stories are crafted, filtered, and interpreted. The filmmakers do not explicitly explain the purpose or mechanics of the production, relying on viewers’ shared cultural and cinematic knowledge to infer the significance of these interruptions. This creates a dual layer of implicational silence: inferential, because the audience must infer how the fragments relate to narrative construction; and presuppositional, because understanding depends on prior knowledge of filmmaking conventions. These silences align with the Gricean maxim of Quantity, as only partial information is provided, compelling viewers to supply meaning through cognitive inference and schema activation. In this way, the structural gap becomes a site where absence generates understanding, and the interplay between diegetic action and production context conveys thematic resonance without explicit exposition.

Another key moment occurs when ‘Alī runs into the camera shop and receives the extraordinary camera from the shopkeeper. The narrative abruptly presents the shop, the strange figure of the shopkeeper in white, and the camera’s hyperbolic capabilities without explaining the logic or reason behind this encounter, exemplifying structural silence through omission and deferred disclosure. The audience is left to mentally connect ‘Alī’s urgent search, the odd camera shop, and the extraordinary abilities of the camera—its capacity to film subatomic particles, traverse the sea, land, sky, and sun—without any explicit explanation of why these elements matter. Semantically, the camera itself, the shopkeeper’s gestures, and the close-up of her wrinkled hand function metonymically, representing the process of capturing and interpreting reality. Metaphorically, these elements suggest human curiosity and the desire to reach beyond ordinary perception: the camera becomes a tangible symbol of ‘Alī’s quest to see, understand, and document the world in ways that surpass ordinary limits. The objects and gestures make abstract ideas of knowledge, discovery, and mediation visible, giving the audience concrete cues through which to interpret ‘Alī’s pursuit.