Woman, Witness, Freedom. Towards a Feminist Historiography of Iranian Cinema

“Martyrdom is a trap for the oppressed.”

Éric Vuillard (The War of the Poor)1Éric Vuillard, The War of the Poor (New York: Picador, 2020), 46.

Introduction

“Jin, Jiyan, Azadî” (“Woman, Life, Freedom”), the central slogan of the feminist liberation movement in Iran, is based on the Kurdish belief that a free society is impossible without the liberation of women. The violent murder of young Kurdish woman Jīnā Mahsā Amīnī (1999–2022) after her arrest by the ‘morality police’ (Gasht-i Irshād) sparked a class-transgressive, decentralized uprising aimed at breaking down the prison walls of fear, punishment and oppression in Iranian society. People from different social classes, generations, and ethnic groups—Kurds, Arabs, Azeris, Baloch—joined the resistance movement.

What is also expressed in the liberation movement’s slogan is a rejection of probably the most powerful necropolitical instrument of repression in the theocracy:2“Moreover I have put forward the notion of necropolitics and necro-power to account for the various ways in which, in our contemporary world, weapons are deployed in the interest of maximum destruction of persons and the creation of death-worlds, new and unique forms of social existence in which vast populations are subjected to conditions of life conferring upon them the status of living dead. […] under conditions of necropower, the lines between resistance and suicide, sacrifice and redemption, martyrdom and freedom are blurred.” See Achille Mbembe, Necropolitics (Durham/London: Duke University Press, 2019), 92. the cult of martyrdom (‘dying in the name of’). The majority of the population no longer wants to die for the “martyr welfare state,”3Cf. Kevin Harris, A Social Revolution. Politics and the Welfare State in Iran (Oakland: University of California Press, 2017). but to live. Women’s struggle against the colonization of their bodies became an inclusive people’s movement demanding basic rights to life. Iranian film history (before and after 1979) not only tells us a pre-history of this struggle—it has also always been part of it.

This article examines the cinematic practices, tactics and aesthetics of liberation developed by female filmmakers after the Iranian Revolution 1979 to the present time. Women’s struggle for liberation runs through the entire history of Iranian cinema like the “ticking of a clock” (as Walter Benjamin would say), longing for condensation into the “strike of the hour”4Walter Benjamin to Max Horkheimer (1935), in Walter Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 3 (1935–38), ed. Michael W. Jennings, Howard Eiland, and Gary Smith (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002), 424. of an overall social movement. The feminist forms of cinema are part of this ticking.

As will be shown, the struggle of Iranian women directors against hegemonic forms of patriarchy not only took place in Iran itself, but also challenged the trademarks of the New Iranian Cinema on an international level of festival policies, which highly insufficiently covered the feminist forms of Iranian cinema. And this despite the fact that statistics “released a few years ago stated that Iran actually has a higher percentage of female filmmakers than America,” as Rakhshān Banī-i‘timād once said in an interview.5Maryam Ghorbankarimi, “Conversation with the Director,” in ReFocus: The Films of Rakhshan Banietemad, ed. Maryam Ghorbankarimi (Edinburgh University Press, 2021), 12-24, 196.

If the word shahīd in Arabic and Persian means “witness,” which originally had nothing to do with blood witnessing (just as the Greek mártys was initially a juridical witness),6There are two classical meanings of shahādat (martyrdom): bearing witness and sacrificing oneself for the sake of a higher truth. These two meanings were not always interconnected. While shahīd in the sense of „witness” is “fairly common in the Qur’an,” the compatibility of this meaning with the later prevailing aspect of “self-sacrifice” was not self-evident from the beginning. Rather, the “Muslim tradition had to invent this connection,” amongst others as “a reflex of late antique Christian usage.” It was the early Christians in the middle of the second century A.D. who, by their (more or less) voluntary death in the arena, appeared as witnesses to a higher truth, thus also giving a new meaning to the commonly used term for witness, namely martyr (Greek martys; Latin martyres). Thus, a term initially used in a juridical context was transformed into the new and until today more dominant meaning of blood testimony in the sense of “sacrificial death for the faith.” —Ravinder Kaur, “Sacralising Bodies: On Martyrdom, Government and Accident in Iran,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 20, no. 3 (2010): 442–60, 447; Keith Levinstein, “The Revaluation of Martyrdom in Early Islam,” in Sacrificing the Self: Perspectives on Martyrdom and Religion, ed. Margaret Cormack (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 78–92, 79. then the feminist films from Iran (and the diaspora) reveal practices of a counter-witnessing that fosters transgenerational as well as class-transgressive solidarity: a witnessing that counters the hegemonic witnessing of male martyrs with singular as well as connected gestures of resistance.

Filming on Many Fronts

After the 1979 Revolution, the cultural functionaries of Islamic guidance attempted to implement a quasi-Islamized version of the “Third Cinema”—which in fact was more a state hijacking of decolonial cinema and a propagandistic exploitation of its anti-imperialist rhetoric.7In order to express the state’s hijacking of the “Third Cinema”, Blake Atwood uses the term “state-controlled postcolonial cinema”. see Blake Atwood, Reform Cinema in Iran. Film and Political Change in the Islamic Republic (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016), 11. However, the authorities’ attempt to homogenize Iranian cinema ideologically and aesthetically has never achieved its goal. Even though the initial aim after the Islamic Revolution was to drive women out of cinematic spaces (both visually and acoustically), the unexpected result of this “purification phase” was an unprecedented opening of the film industry to women. Although they had to adhere to the strict modesty rules of veiling both in front of and behind the camera, cultural functionaries began to realise in 1985 (i.e. during the war), that they had to invest in a new generation of young female filmmakers in order to boost the weakened film industry. 8“A unique and unexpected achievement of this cinema has been the significant and signifying role of women both behind and in front of the camera. […] What is unique is the inscription of modesty rules and what is unexpected is that more women feature film directors emerged in a single decade after the revolution than in all the preceding eight decades of film making – and this in a patriarchal and traditional society, which is ruled by an Islamist ideology that is highly suspicious of the corruptive influence of cinema on women and of women on cinema. […] The strong presence of women behind the camera was officially recognized in 1990, when the 9th Fajr Film Festival – the country’s foremost national film event – devoted a whole program to the ›women’s cinema.” This cinema is very diverse, as women are involved in all aspects of feature, documentary, short subject, and animated films as well as in all aspects of television films and serials production. Some of the filmmakers are quite versatile and they make documentaries, television soap operas, and feature films. Of particular significance is the emergence of a new cadre of feature film directors (and prominent actresses) trained after the revolution, who have begun to make their mark on the cinema and provide powerful role models for other women. Hamid Naficy, “Veiled Voice and Vision in Iranian Cinema: The Evolution of Rakhshan Banī-i‘timād’s Films,” Iran Chamber Society (2000), accessed August 20, 2025, https://www.iranchamber.com/cinema/articles/veiled_voice_vision_iranian_cinema1.php. In addition, many female directors who had started out in state television then switched to the film industry (such as Rakhshān Banī-i‘timād around 1987), as the censorship conditions there were not quite as rigid. Gradually, Iranian female filmmakers turned the medium film into a “Trojan horse” through which they smuggled multi-layered counter-images and “counter-memories”9Counter-Memories re-member official versions of history against the grain. They destabilize the mainstream of uniform memories shaped by epistemic oppression, red lines and power effects. See Matthias Wittmann and Ute Holl, ed., Counter-Memories in Iranian Cinema(Edinburgh University Press, 2021). into the public sphere, exposing all facets of the widening gap between the propagandistically claimed achievements of the Revolution and actual social injustices, also maintaining a call for justice against the traps of what is often called “state reform.”

Thus, despite the state architects’ attempts to “purify” the language of post-Revolutionary film, Iranian cinema succeeded in developing a fascinating variety of resistant forms whose feminist facets were, however, inadequately represented by the distribution routines of international festival networks. The Iranian women filmmakers had to film on many fronts, as the title of this subchapter suggests – and as will be shown in detail below.

While Iranophile festival audiences in Europe were under the spell of the so called New Iranian Cinema—and wondered why women in ‘Abbās Kiyārustamī’s films were constantly absent (this was to change abruptly with Ten, 2002)—the presence of Iranian women behind and in front of the camera was consistently overlooked by the same audiences. Thus, their struggle against hegemonic forms of patriarchy took place not only in Iran itself, but also on a transnational level with regard to festival policies and trademarks to which the Iranian cinema was confined after the Islamic Revolution (1979), and especially after the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988). Simple, allegorical stories about rural life had been foregrounded by international festival networks, which led to the impression in Europe that “there is no electricity and no telephone in the whole of Iran,”10Quoted according to Birgit Glombitzka, “Hassliebe mit Tradition,” TAZ, September 15, 2003, accessed July 20, 2025, https://taz.de/Hassliebe-mit-Tradition/!710766/ as director and producer Mohammad Farokhmanesh once expressed it from a critical diaspora perspective.

At a time when ‘Abbās Kiyārustamī, for example, considered Iranian cinema to be Iran’s most important export alongside “pistachios, nuts, carpets, and oil”11Miriam Rosen, “The Camera Art: An Interview with Abbas Kiarostami,” Cineaste 19, nos. 2-3 (1992): 40. (most likely including his own films), the no less significant films of Rakhshān Banī-i‘timād, the pioneer of socially critical film realism after the 1979 Revolution, were still decades away from gaining recognition in Europe. The following subchapter provides a closer look at Banī-i‘timād’s cinematic techniques of debunking the façade of the official success stories of the revolution, and documenting the daily struggle of those who have to live in the shadow of the state honoured martyrs.

Debunking the (Self-)Sacrificial Paradigm of State Martyrdom

Banī-i‘timād, who underwent a training programme at National Iranian Radio and Television (NIRT) before the Iranian Revolution, continued to pursue documentary projects after the Revolution, not only sharing the film footage—in the spirit of a Cinéma Verité-ethos of gift and counter-gift12Jean Rouch, “The Camera and Man”, in Ciné-Ethnography, ed. and trans. Steven Feld (London/Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 29-48, 44.—with the people who had been filmed, but also using the films to persuade the city administration to implement reforms, especially when it came to improving living conditions in the shanty towns of Tehran.13See Maryam Ghorbankarimi, “Rakhshan Banietemad’s Art of Social Realism: Bridging Realism and Fiction,” in ReFocus: The Films of Rakhshan Banietemad, ed. Maryam Ghorbankarimi (Edinburgh University Press, 2021), 189-205, 196. Thus, Banī-i‘timād supported the 1979 Revolution as a secular critical intellectual rather than as a religious fundamentalist. In her words, “Our society needed a cinema with a different point of view.”14Shiva Rahbaran, “6. Rakhshan Banietemdad: Cinema as a Mirror of the Urban Image,” in Iranian Cinema Uncensored. Contemporary Film-Makers since the Islamic Revolution (London/New York: I. B. Tauris, 2016), 12-46, 131f. She remained committed to this cultural revolution in her own resistant way and dedicated her films to the micro-histories of suppressed voices that were able to brush the official success stories of war and revolution against the grain.

If censorship is as a set of permanently shifting, partly unwritten red lines that compel filmmakers to play a hide-and-seek-game called symbolism, then Banī-i‘timād’s semi-fictional, semi-documentary approach can be considered as a set of tactics in order to avoid pursuing this game. Instead, her post-revolutionary “street level perspectives”15Blake Atwood, Reform Cinema in Iran. Film and Political Change in the Islamic Republic (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016), 77. make visible and audible the materiality of tensions between conflicting social realities that are produced by the censorship of the city Teheran itself: a topology of boundaries, class differences and social limitations respectively exclusions, a system of all sorts of unequal distributed capital – social, cultural, economic, symbolic capital – and incorporated rules, schemes of perception and classifications.

Under the Skin of the City (Zīr-i Pūst-i Shahr, 2001), the story of the struggle for survival of a courageous “Mamma Tehrani” named Tūbā (Gulāb Ādīnah), set in the poor south of Tehran, can be seen as a pivotal film in Banī-i‘timād’s cinematic social history. The blue-collar (or rather, “black-chador”) worker Tūbā is not only a composite figure made up of research and invention (like so many of Banī-i‘timād’s characters), but also a recurring figure, a revenant in Banī-i‘timād’s feature films. Before Under the Skin of the City, she had already made an appearance in May Lady (Bānū-yi Urdībihisht, 1997). Years later she would reappear in Tales (Ghissah-hā; 2014), thus giving a whole range of Banī-i‘timād’s feature films the character of a semi-fictional, semi-documentary long-term observational films, comparable to Volker Koepp’s Wittstock I – IV (1975), Nicolas Geyrhalter’s Over the years (Über die Jahre; 2015), Michael Apted’s63 Up (1964), Richard Linklater’s Boyhood (2014), or Želimir Žilnik’s Kenedi-Trilogy (2003-2007).

Figures 1 & 2: Screen Grabs from Under the Skin of the City (Zīr-i Pūst-i Shahr), directed by Rakshān Banī-i‘timād, 2001.

Over the course of several feature films, one follows various phases of a possible, imaginable subaltern life in southern Tehran—and listens to Tūbā’s increasingly severe cough as an effect of the murderous air both in the textile factory and in the smog of Tehran itself. Thus, the longitudinal study is a congenial accomplice to Tūbā’s long-term exposure to health risks. Long-term observational films in general often imply a critical attitude towards progress. They ask where time has gone. Banī-i‘timād’s socio criticism asks what has become of the expectations and promises of the revolution, and which events (or non-events) have altered the rhythms of life—or not altered, but hardened them. In doing so, they bring a sluggish, non-linear counter-time into play that subverts the martyrological and teleological model of time.

The mythical circularity of the time of the martyr (with its messianic telos of a future of redemption) is exposed by Banī-i‘timād’s social critique as a tough, circular time that does not pass because it is not allowed to pass—and because class relations are supposed to remain unchangeable. According to Jacques Derrida, “simultaneity is the myth of a total reading or description, promoted to the status of a regulatory ideal.”16Jacques Derrida, “1. Force and Signification,” in Writing and Difference, trans. Alan Bass (London/New York: Routledge Classics, 1978), 24. Banī-i‘timād’s time-critical art is entirely in line with Derrida’s criticism of totalitarian concepts of time: it makes visible the cracks that the myth of a total availability of time—as the simultaneity of past, present, and future—attempts to obscure. This becomes particularly clear in one scene of her earlier feature film The Blue Veiled (Rūsarī Ābī, 1995): While the upper-class widower and owner of a tomato sauce factory, Rasūl Rahmānī (‘Izzatallāh Intizāmī), prays with his family in the dining room of his luxury mansion and remembers the martyrs of the past (“Yā ‘Alī! Yā ‘Alī! Purify our hearts with your gifts. If people believe in the poor …”),17The Blue Veiled, directed by Rakshān Banī-i‘timād (Iran, 1995), 00:31:00-00:32:37. the domestic servants have to wait in the kitchen to be allowed to serve tea to the upper-class family after the endless prayers have ended.

Banī-i‘timād unmasks the hypocrisy of religious rituals (especially those dictated by the state) and lays open the empty remains of the promises of what was once called liberation theology or Alavid Shi’ism by ‘Alī Sharī‘atī: a revolutionary political position and a counter-hegemonic utopia based on freedom, social justice, spirituality, based on a red, action-oriented rather than a black, mourning-oriented Shiism. What had promised decolonization and liberation before the Islamic revolution became a necropolitical instrument after the revolution, assisting the government to colonize its own population – especially the lower classes. Banī-i‘timād thus exposes religion as a governmental technique that uses rituals to keep people trapped in a self-sacrificial state of waiting for changes never to come.

The “martyr welfare state”18Cf. Kevin Harris, A Social Revolution. Politics and the Welfare State in Iran (Oakland: University of California Press, 2017). separates the “space of appearance”19Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (University of Chicago Press, 1998), 199ff. of male martyrdom – as a public act of sacrifice that deserves recognition and remembrance – from the private testimony of women, who ultimately stand in the service of commemorating the heroic martyrdom of men. The time of male martyrdom, which is worth being told and re-presented in public spaces through murals and rituals (among other things), is passed on by the caring testimony of mothers, wives and daughters. Being a martyr also means being allowed to demonstrate in public the (supposed) freedom of risking one’s own life as a hero, while the lives of the female caregivers have no right to risk their life in public space.

Banī-i‘timād’s cinematic counter-witnessing confronts the hegemonic body testimony of male martyrdom and the symbolic vocabulary of state martyr propaganda with the singular times and resistant gestures of women portrayed in her films. In this way, Banī-i‘timād develops counter-martyrological forms of cinematic eye-witnessing that, above all, create frictions between political promises and social realities, dealing with solidarity between silenced voices—solidarity that also transgresses class boundaries. Her films try to carve out how ordinary people organize themselves in communities, networks, and grassroots movements,20See Asef Bayat, Street Politics. Poor People’s movements in Iran (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997). and how women from the middle-class (like Banī-i‘timād herself) try to support these grassroots movements.

Revisiting Iranian film history as a history of feminist counter-testimony therefore also means discovering forms of resistance in different strata of society. In addition, the films often raise the question of how solidarity between these social strata is possible. The following subchapter examines how Iranian women filmmakers deal with various forms of resistance within different social strata – and with forms of solidarity across these strata. The exploration will reveal a whole variety of feminist “passion plays” that can be found in the examined films, passion plays between (upper) middle-class feminism and subaltern articulations of resistance.

Middle-class Feminism and Subaltern Forms of Resistance

If we extend the radius of Tūbā’s family and in particular the paths of her son Abbas (Muhammad Rizā Furūtan), who delivers pizzas, beyond the boundaries of the diegetic world of Under the Skin of the City and move a little to the north, then we could imagine arriving at Tehran’s middle class and Banī-i‘timād’s self-reflexive, meta-film May Lady (Bānū-yi Urdibihisht, 1998). The film tells the story of 42-year-old documentary film director Furūgh Kiyā (Mīnū Farshchī). Furūgh is divorced, living with her adult, jealous son and having an affair with a man we never see, but whose presence is established through phone calls, letters and voice-over poems. In addition, she is starting to work on a TV reportage about an exemplary mother of Iranian society. The problem is that during her research, she is confronted with such a variety of individual mothers from different social classes that she finds herself increasingly unable to select an exemplary mother who would fit into the nationalist category of “motherland” (mādar-i-vatan), as the television company expects her to do. Thus, Banī-i‘timād’s documentary and feature films constantly confront us with crucial ethical dilemmas of ethno-sociography: How to keep in touch with multiple layers of society? How to avoid “speaking for” (e.g. the subalterns) when making committed documentaries? What does it mean to pick up one individual case, to decontextualize it, and transform it into a category, an exemplary case for society while thousands of other singularities have been de-selected? May Lady deals above all with the conflict between Islamist role expectations imposed on women (who are supposed to become the ideal mother) and the struggle for female autonomy in work and love life.

Figures 3 & 4: Screen Grabs from May Lady (Bānū-yi Urdībihisht), directed by Rakhshān Banī-i‘timād, 1998.

Banī-i‘timād, who as a middle class woman would not use the label “feminist filmmaker” for herself in order not to appear didactic or elitist towards subalterns,21Cf. Asal Bagheri, “The Blue-veiled: A Semiological Analysis of a Social Love Story,” in ReFocus: The Films of Rakhshan Banietemad, ed. Maryam Ghorbankarimi (Edinburgh University Press, 2021), 140-158, 142. was for a long time completely disregarded by the trademarks of international festival politics and their all-too-narrow prey scheme of “allegorical arthouse cinema from Iran”. The same is the case for feature films such as Tahmīnah Mīlānī’s political melodrama The Hidden Half (Nīmah-yi Panhān, 2001) and Manīzhah Hikmat’s powerful prison epic Women’s Prison (Zindān-i Zanān, 2002).

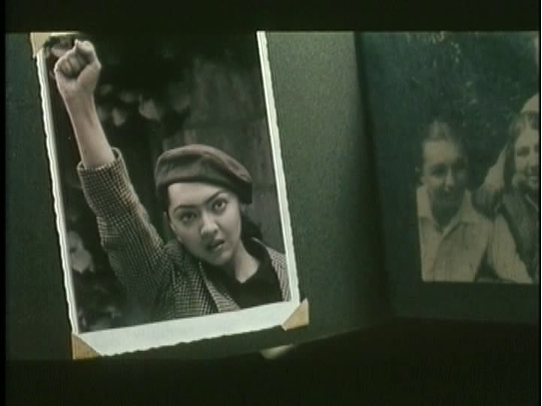

Mīlānī’s The Hidden Half tells the story of Farīshtah (Nīkī Karīmī), an upper-class protagonist and a former left-wing radical who decides to tell her husband, a Tehrani judge, about her previously hidden political activities in the period immediately following the revolution. The film’s structure is comparable to Max Ophüls’ Letter from an Unknown Woman (1948), since Farīshtah’s husband ends up reading her confidential writings and discovers her secret, hidden life. Using a series of flashbacks, the film portrays the repression unleashed by Islamic fundamentalists against gauchistes and politically committed women after 1979. Mīlānī’s film establishes counter-memories that challenge the official success stories of revolution, war and state martyrdom from the perspective of forgotten and repressed stories. What is at stake then is the quest for the crushed and silenced individuals or collectives and the question of representation: How to turn the grand narratives into minor or singular memories of revolt, uprising, and feminist dissidence? In contrast to Banī-i‘timād’s films, The Hidden Half arguably reflects the widespread hopes for change embodied by Sayyid Muhammad Khātamī who was 1997 elected as the president and was in office until 2005.

Figures 5 & 6: Screen Grabs from The Hidden Half (Nīmah-yi Panhān), directed by Tahmīnah Mīlānī, 2001.

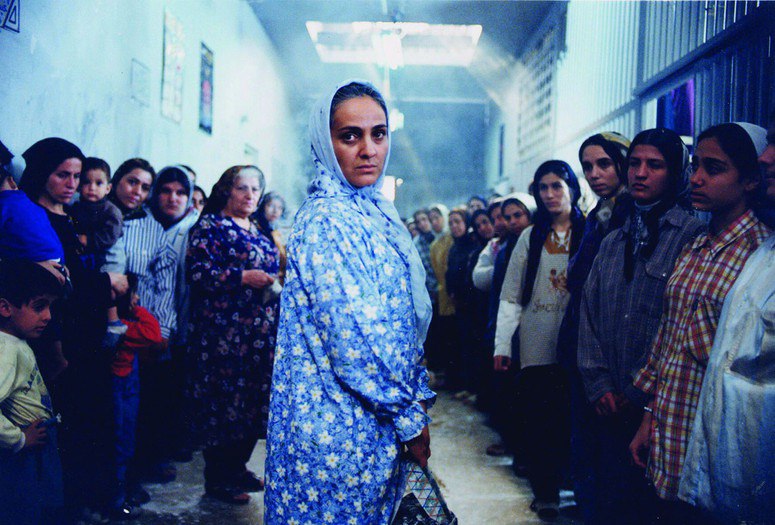

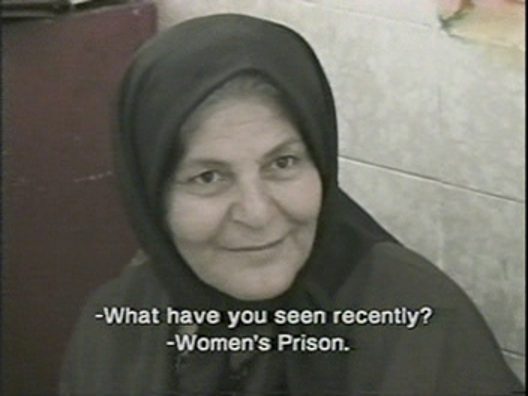

A particularly epic depiction of women’s struggle for liberation can be found in Manīzhah Hikmat’s feature film Women’s Prison (Zindān-i Zanān, 2002), which was no less popular than Banī-i‘timād’s Under the Skin of the City and reflects social conditions through the prism of a prison. Hikmat’s massive prison epic, spanning seventeen years, can be compared to Banī-i‘timād’s films in that in both cases careful milieu studies are turned into fiction—although Women’s Prison is also a gripping genre film that works with allegorical condensations. Revolving around the axis of a bitter conflict between rebellious inmate Mītrā (Rawyā Nawnahālī) and prison guard Tāhirah (Ruyā Taymūriyān), the film tells stories of power, sexuality, and violence, but also resistance through women’s solidarity. The now banned film was a box office success after release in Tehran, not least because it was regarded by the female population in particular as an echo chamber of their own experiences of oppression, and longing for resistance.

Figure 7: Screen grab from Women’s Prison (Zindān-i Zanān), directed by Manīzhah Hikmat, 2002.

The resistant gestures of women in Iranian cinema are not always grand, revolutionary gestures of feminist, well-educated middle-class activism. Especially when it comes to documenting subaltern articulations of revolutionary consciousness, and emancipatory struggles outside the discourses of Western, didactic feminism, it becomes especially important to look at female filmmakers who have remained in Iran in order to stay in touch with what Asef Bayat calls the “urban disenfranchised.”22See Asef Bayat, Street Politics. Poor People’s movements in Iran (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997), 5.

In her documentary film The Ladies Room (Zanānah, 2003), the underground filmmaker Mahnāz Afzalī introduces us to a women’s toilet in a Tehran park as the only place where sex workers, heroin addicts, and runaway daughters can find and create an aesthetic “space of appearance” (as Hannah Arendt would call it) for their experiences of violence (be it structural or domestic).23Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (University of Chicago Press, 1998), 199ff. At the same time, this public toilet is transformed into a protective, semi-private space in which women can reclaim their right to intimacy as protection against domestic and state violence.

Following the traditions of cinéma vérité, Afzalī used special questioning techniques to gain the trust of these stunning women and persuade them to create performances that resulted in an extraordinary feminist ta‘ziyah in the ladies’ toilet. The women not only change roles (sometimes they are performers, sometimes they are the listening audience), but also enact a process of “truth-telling” 24Cf. Michel Foucault, “The Courage of Truth: The Government of Self and Others II,” in Lectures at the Collège de France 1983-1984, trans. G. Burchell (London: Picador, 1984). (Parrhesia) against power. The protagonists regain the right to play the roles and wear the masks they want to wear—and not those that are forced upon them. During the passion play, not only are worries, fears and experiences of violence shared, but also excellent jokes critical of religion. We also learn that the system not only provides no rights for sex workers—and nothing but penalties ranging from imprisonment, flogging to the death penalty—but also refuses war-wounded women the status of “living martyrs,” and hence financial benefits.

Figures 8-10: Screen Grabs from The Ladies Room (Zanānah), directed by Mahnāz Afzalī, 2003.

From a film-historical in-depth perspective, the feminist re-coding of ta‘ziyah as undertaken in The Ladies Room can be traced back to Bahrām Bayzā’ī’s The Ballad of Tārā (Charīkah-yi Tārā, 1979): In contrast to traditional mourning rituals, it is the widow Tārā (Sūsan Taslīmī) who rides the white horse instead of Husayn Ibn ʿAlī (626–680 CE). Above all, she does not want to die and become an allegorical, martyred body, but rather to live and become an independent woman. She very well knows that “martyrdom is a trap for the oppressed.”25Éric Vuillard, The War of the Poor (New York: Picador, 2020), 46. Accordingly, Afzalī’s film also gives the women of the Ladies Room the opportunity to free themselves from the role they are supposed to play according to the mythological battle at Karbala, and especially the story about Husayn’s sister Zaynab.26Cf. Kevin Schwartz and Olmo Gölz, “Negotiating Gender During Times of Crisis: Visual Propaganda from the Iran-Iraq War to Covid-19,” British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies (BRJMES), Special Issue: Cultural Production, Propagandas, and Negotiating Ideology in Iran, ed. by Goulia Ghardashkhani, Olmo Gölz und Kevin Schwartz (2024), accessed September 2025, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13530194.2024.2342178. Instead of performing the classic role of Zaynab – and witnessing the public martyrdom of men –, the women portrayed by Afzalī are given the opportunity to bear witness to their own heartfelt passions.

Figure 11: Screen Grab from The Ballad of Tārā (Charīkah-yi Tārā), directed by Bahrām Bayzā’ī, 1979.

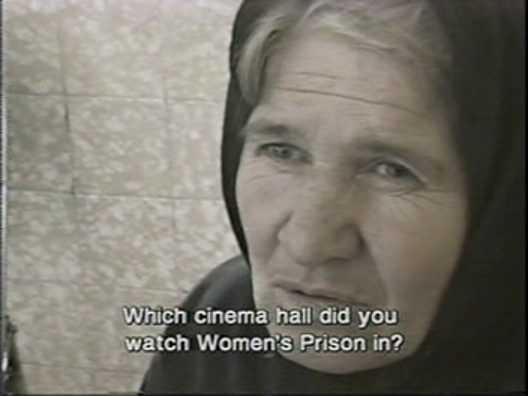

If, according to Arendt, the reality of inner life can only be constituted through “being seen and heard,” then Afzalī has succeeded in developing a cinematic realism that does justice to the “passions of the heart, the thoughts of the mind, the pleasure of the senses,”27Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (University of Chicago Press, 1998), 50. which cannot exist as long as they are not allowed to claim any public space, any form of participation in a shared reality. While Hikmat’s feature film is about the prison as a microcosm of society, Afzalī presents the ladies’ toilet as a heterotopia and counter-space in order to uncover an alternative her-story of resistance. Remarkably, the popularity of Hikmat’s feature film becomes evident in Afzalī’s cinema verité-documentary when a sex worker during an interview names Women’s Prison as her favourite film because it shows the prison walls of society literally encircling the female body.

Also particularly noteworthy is a second documentary by Afzalī, which offers multi-layered insights into the misogynistic justice system of Iranian society. Using a refined montage of self-shot material and found footage (mainly home videos), The Red Card (Cārt-i Qirmiz, 2006) deals with the show trial against Shahlā Jāhid (1969–2010), who was sentenced to death because, as the lover of former national striker Nāsir Muhammadkhānī, she was accused of murdering his wife. The film is the most disturbing document imaginable of how “female guilt” is constructed in court. It is about the punishment of a woman whose neck had to fit into a socially prepared noose because she tried to live a love affair with a soccer star the way she wanted to. It is all the more remarkable that Afzalī succeeds in doing the almost impossible: In the midst of a misogynistic courtroom established to construct female guilt, the camera is consistently adjusted in such a way that the perspective of the accused victim is maintained and not denounced. It is not without reason that director Afzalī names Jāhid as co-director in the credits.28Afzalī’s The Red Card can be linked to Seven Winters in Tehran (2023), Steffi Niederzoll’s documentary debut, which contains secretly filmed footage and reconstructs the case of student Rayhānah Jabbārī (1987-2014), who was sentenced to death in 2007 for defending herself against an attempted rape. Before her execution, Jabbari was able to fight for a public voice from inside the women’s prison, supported by her parents, friends, and social media. Like the fictional Mītrā in Hikmat’s Women’s Prison, she also campaigned on behalf of her fellow inmates, who now pass on the songs Jabbari sang in prison to their children.

|

|

Figures 12-14: Screen Grabs from The Red Card (Cārt-i Qirmiz), directed by Mahnāz Afzalī, 2006.

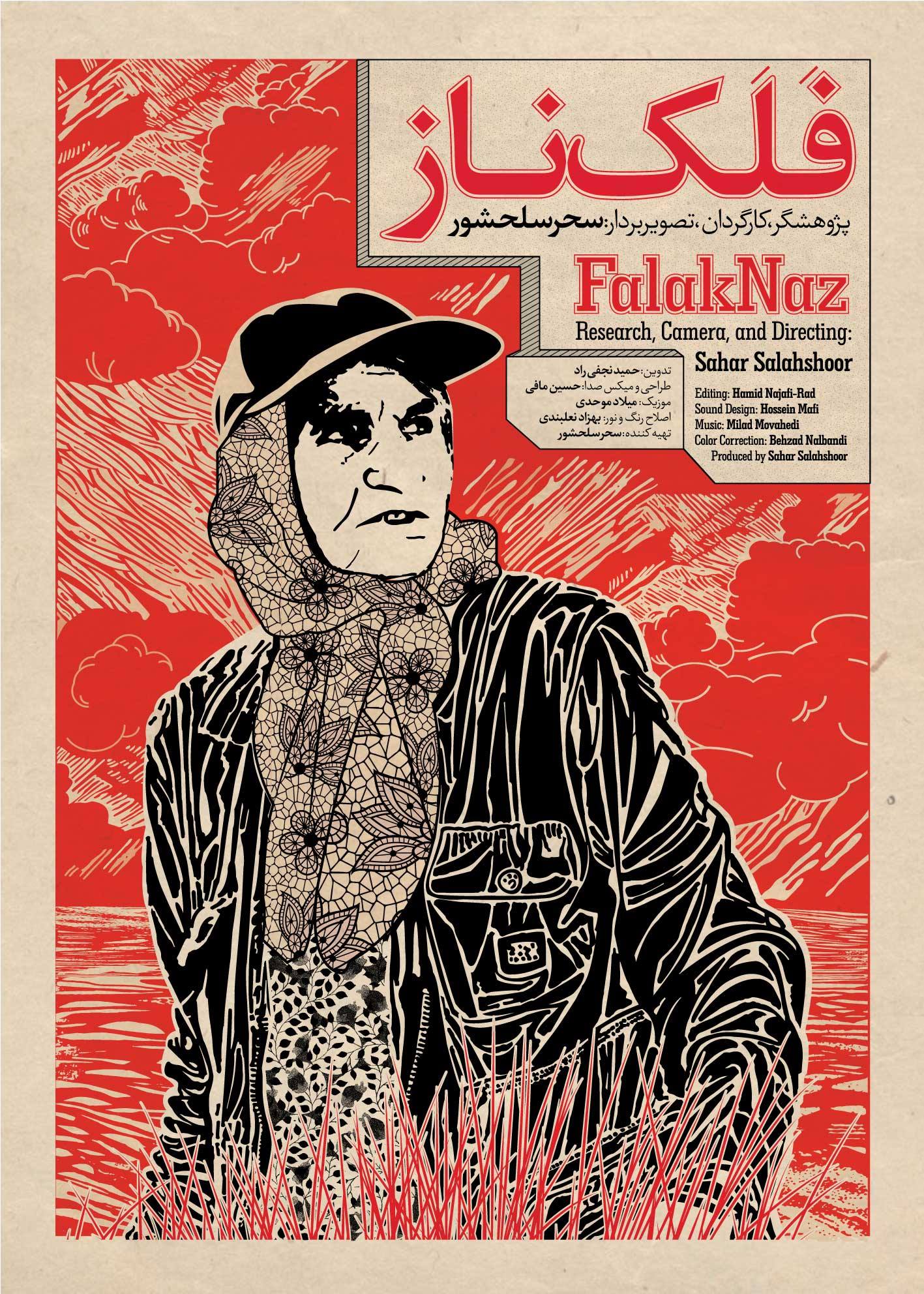

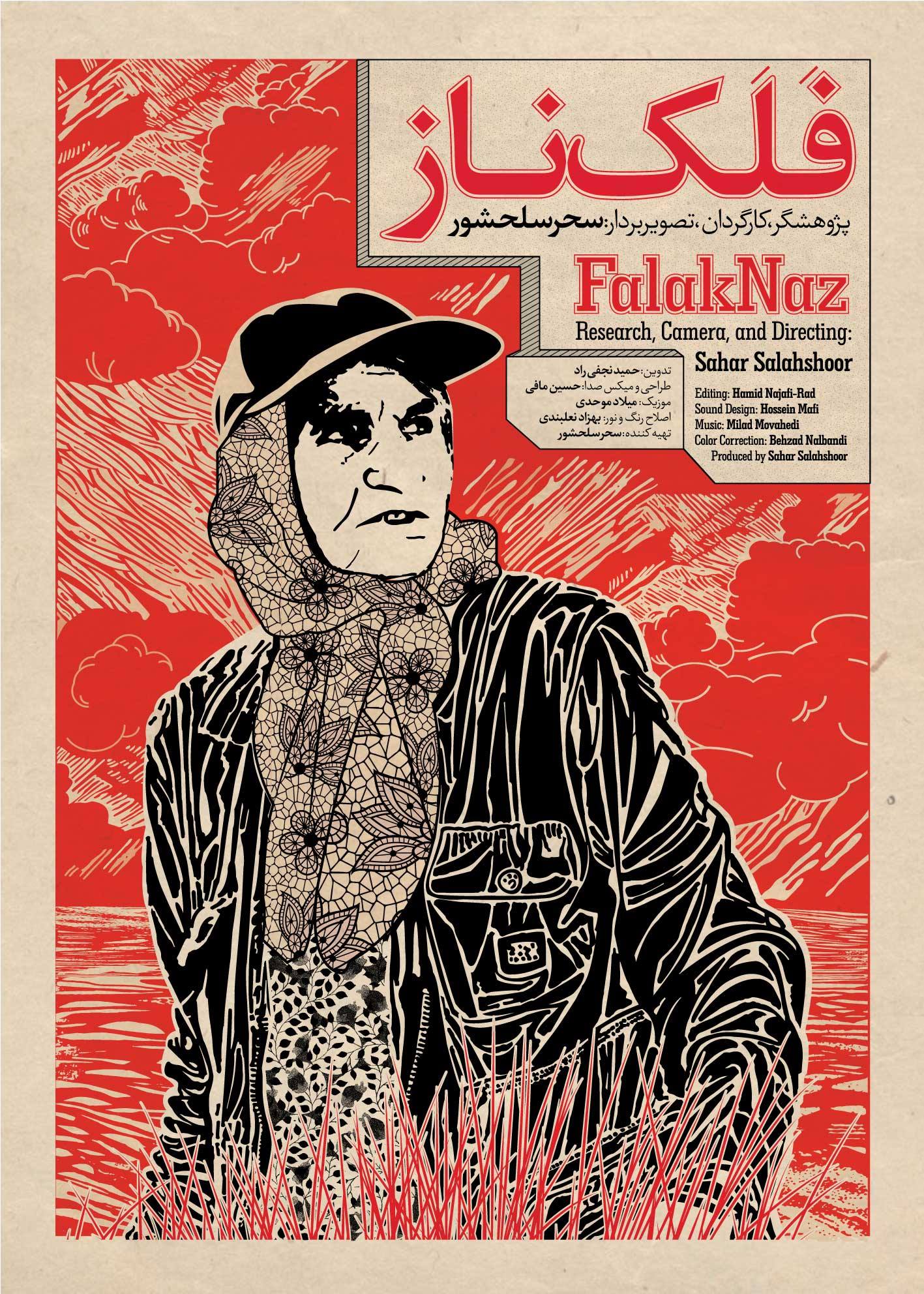

Another example of the practices of cinema verité is Sahar Salahshūr’s outstanding documentary film Falak’nāz (2015), which uses a hand-held camera and consistently rhythmic editing to portray the art of living and surviving of a Bactrian peasant woman. Falak’nāz, whose face is visibly carved and wrinkled by life, has to fight on various fronts in the western Iranian village of Fath-Ābād: against the dry earth, but also against the rigidity of village traditions, which she confronts with counter-stubbornness and subtle ingenuity. Salahshūr explores the social village structures through the lens of a subaltern peasant personality who, amid clearly defined roles, embodies an alternative, emancipatory model without acting in a consciously feminist or programmatically transgender political manner. The fact that Falak’nāz owes her local political authority to a rather rough, traditionally male habitus and, with her sharp-edged face under her headscarf, always looks like a cross-dresser, is not exposed by the documentary, but taken for granted. As a side story, the documentary thus also portrays the body as a venue for the most diverse role expectations between mother, politician, field worker and shopkeeper.

Figure 15: Screen Grab from Falak’nāz, directed by Sahar Salahshūr, 2015.

Thus, a leitmotif has emerged that runs through all the films and social milieus reflected above: The issue is not only the female body as an intersectional battleground of conflicting interests and forms of repression, but also as a self-empowering site for the development of diverse languages of resistance on many different frontlines. “Resistance” does not always refer to grand, revolutionary tactics, but can also point to emancipatory gestures whose liberating power arises from an awareness that there could be a different, alternative life. Although many female protagonists do not succeed in liberating themselves from constraints, they are very well able to recognize the social conditions that plunge their lives into manifold conflicts in order to reject or transcend the roles they are forced to play.

It is precisely these tensions and transgressions that are also the subject of Fā’izah Azīzkhānī’s entertaining post-Kiyārustamī film-within-a-film-construction For a Rainy Day (Rūz-i mabādā, 2015), a film that brings the social panorama, as reconstructed in this article, back to the middle class. For a Rainy Day is the story of a daughter shooting a documentary about her mother who, after a dream, imagines that she will soon die and finds herself torn between superstition, traditional role expectations, and (maternal) duties, but also between anarchic desires for self-fulfilment and revenge. In one hilarious scene, the mother becomes so pathetically involved in making a video testament (with quotes from the Koran) that the daughter feels reminded of a suicide bomber’s video message. Gradually, the documentary film project turns into a wish fulfilment machine for everyone involved. Mother and daughter even manage to persuade the film star Hadiyah Tihrānī to take part. Hence, in addition to a class-transgressive solidarity, the feminist forms of cinematic resistance also create a strong inter-generational solidarity. The article will come back to this aspect at the end.

Collective and Auto-Ethnographic Filmmaking

It should be noted at this point that it is above all in the form of collectives that Iranian feminist filmmaking not only organizes itself, but also draws its resilience within a totalitarian regime. This becomes particularly evident, as if through a burning glass, when one considers the auto-ethnographic film Profession Documentarist (Hirfah Mustanadsāz) from 2014, made in the aftermath of the Green Movement.

The film consists of seven episodes by young female directors (Shīrīn Bārqnāvard, Fīrūzah Khusravānī, Farahnāz Sharīfī, Mīnā Kishāvarz, Sipīdah Abtāhī, Sahar Salāhshūr, and Nāhīd Rizā’ī) who have found highly original and idiosyncratic ways of working through traumas, doubts, and fears. Some of the filmmakers live in Iran, some went into the diaspora, currently live in France, Australia, or Germany, and are extremely productive, with films such as The Art of Living in Danger (2020) by Mīnā Kishavarz, My Stolen Planet (2024) by Farahnāz Sharīfī, or Density of Emptiness (2023) by Shīrīn Barqnavard).

Working together, the filmmakers developed a strong, collaborative form to film against the visible and invisible prison walls of Iranian society. How can a filmmaker give a voice to all the other silenced women in a society that strategically suppresses the vocal sphere (and especially the singing voices) of women? How to deal with (war) traumas and fears, but still remain open to the future? How can a possible world be filmed? How can films be imagined that are not allowed to exist? And how can the walls of a walled society be overcome with cinematic means in order to create windows to the public sphere, and allow resistance movements to emerge from private networks? What are the liberating effects of filmmaking? These are questions that drive all the contributions to this omnibus film and give it a high degree of actuality.

In one episode (by Sahar Salahshūr), the protagonist observes the walls of Ivīn Prison through her apartment window, and as this view begins to invade her privacy like a “vampire”, her filmmaking becomes a weapon and a shield—a kind of “screen” —against the intrusion of a prison architecture that can be understood here both literally and synecdochically, as part of a fait social total.29Marcel Mauss, The gift: Forms and functions of exchange in archaic societies (London: Cohen & West, 1966), 76-77. Even though filmmaking creates a protective, apotropaic shield against the outside world, it is impossible to escape the entanglement of private and public space.

However, it is important to view these episodes in their overall context, as taken together they show that feminist agency is based primarily on cooperation and collectivity. What connects and characterizes the latest films by female directors from Iran (and also from the Iranian diaspora) is the search for stories about feminist resistance movements that span generations and different social classes. This search no longer takes place against the backdrop of the trauma of a lost revolution (which would be a characteristic feature of the films of an older generation), but is driven by the need to pass on testimonies (“Who bears witness for the witnesses?”) and to create a living, performative, and popular memory through the medium of film.

Figures 16-17: Screen Grabs from Profession Documentarist (Hirfah, Mustanadsāz), directed by Shīrīn Bārghnāvard, Fīrūzah Khusravānī, Farahnāz Sharīfī, Mīnā Keshāvarz, Sipīdah Abtāhī, Sahar Salahshūr, and Nāhīd Rizā’ī, 2014.

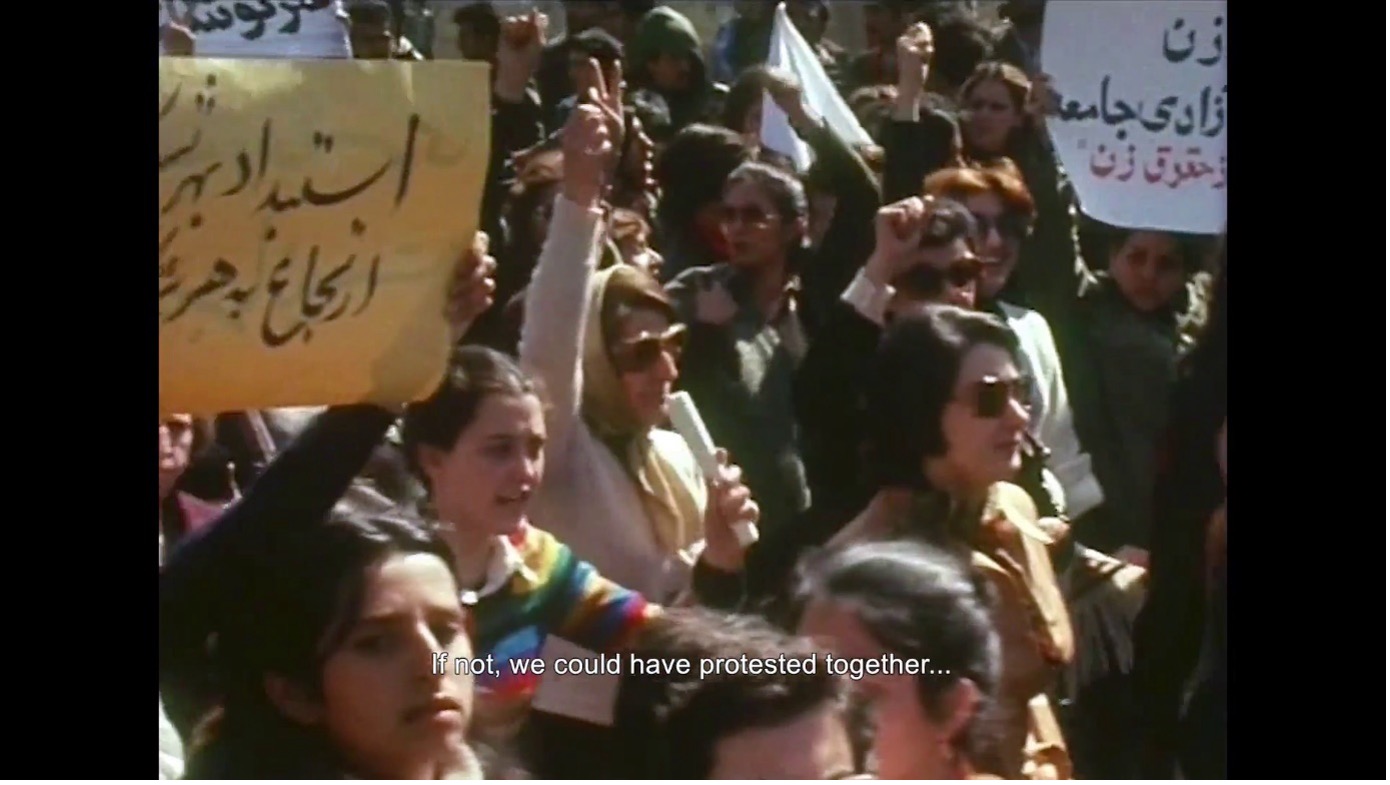

Another film dedicated to the work on transgenerational, popular memory is The Art of Living in Danger (2020), in which Mīnā Kishāvarz imagines a dialogue with her grandmother, who committed suicide at the age of 35 during the pre-revolutionary period after being forced into marriage at a young age. In the course of this conversation, Kishāvarz imagines a transgenerational encounter at the site of the 1979 revolution. “Nurījān, you had passed away by then. And I had not been born yet. If now, we could have protested together for freedom and justice.”30The Art of Living in Danger, directed by Mīnā Kishāvarz (Iran/Germany, 2020), 00:03:33-00:03:51.

However, the film also addresses the difficulties of establishing cross-class solidarity in the face of unequal opportunities (for emancipation). When the women’s rights activists portrayed in the film collect stories of oppressed women in the city of Marīvān (in western Iran) to support their efforts, they are confronted with criticism from many of the local women, who accuse the middle-class activists of not knowing enough about local social problems, especially of the lower-classes.

“There is no way for women to earn a living so they are all dependent on man … they even need the permission to leave home … When a woman marries here, they are no longer allowed to be friends with anyone they knew before the wedding… How shall we deal with such limitations … If a daughter wants to finish her studies at the university, she might never get married … If it took you, a counselor, eight years to gain independence (from your violent husband), how can a woman from my village, without any support, save herself?”31The Art of Living in Danger, directed by Mīnā Kishāvarz (Iran/Germany, 2020), 00:55:30- 00:58:22.

This critical statement is adressed to the women’s rights activist by a female resident at the local gathering. The film thus also shows that it is social inequality that renders cohesion amid diversity so difficult and challenging. It is, above all, the transformation of fear that interests filmmaker Kishāvarz in her cinematic counter-testimony, which counters the hegemonic testimony of male martyrs with cross-generational gestures of resistance. In this regard, entirely in line with the famous dictum by Theodor W. Adorno that the “purpose of revolution” is more than ever “the abolition of fear” (Adorno in a letter to Walter Benjamin in 1936).32Ernst Bloch, Walter Benjamin, Theodor Adorno et al., Aesthetics and Politics (London: Verso Books, 1980), 125.

Figure 18: Screen Grab from The Art of Living in Danger, directed by Mīnā Kishāvarz, 2020.

Archive footage documenting freedom from fear has remained important in Iran’s public revolutionary imaginary to this day: if there are images from the post-revolutionary period that the Islamic Republic’s propaganda machine was never able to appropriate and incorporate, then these are the images of the protests of May 8, 1979, the International Women’s Day, when thousands of women—with and without headscarves— took to the streets of Tehran in a united, cross-class protest against the “mandatory hijab” announced by Ayatollah Khomeini.33See Mouvement de libération des femmes iraniennes, année zéro, directed by Sylvina Boissonnas, Claudine Mulard (France, 1979), 13 min., color, 16 mm.

Films like Profession Documentarist and The Art of Living in Danger show very impressively that Iranian women are at the forefront when it comes to autoethnographic essay films, performative documentaries and the genre of auto-fiction.This can —mutatis mutandis—also apply to films from the Iranian diaspora. Only one example shall be given here in detail:

A remarkable auto-ethnographic and auto-fictional film that uses diasporic film spaces to perform a kind of counter-witnessing is Nargis Kalhur’s film Shahid (Shahīd, 2024) about an Iranian woman living in Germany who wants to break away from her past by changing her name. “Yes, I want Shahīd out of my name!”34Shahid, directed by Nargis Kalhur (Germany, 2024), 00:13:42. says Nargis Shahīd Kalhur (played by Bahārak ‘Abd-‘Alīfard) to her therapist, who is supposed to prepare a “psychological assessment of mental stress.” Thus, Nargis, daughter of a former Ahmadīnizhād official, who has been living in Germany since 2009 (after applying for political asylum), enters the fiction of her own film in order to change her name, since in the non-fictional reality it is precisely this name that prevents her from escaping the patriarchy of her country of origin. Thus, it is definitely not about longing to return—a trope with which the diaspora has all too often been re-essentialised. Instead, Kalhur’s “Cinemigrante”35“Cinemigrante. Narges Kalhor about Shahid,” Filmdienst Online (2024), accessed September 2025, https://www.filmdienst.de/artikel/68059/interview-narges-kalhor-shahid. (a term she likes to use) is about diaspora as dispersion and distraction. This also means using diasporic film spaces as a medium to portray bodies in their transcultural tension between times and places, liberations and constraints.

Figures 19-20: Screen Grabs from Shahid, directed by Nargis Kalhur, 2024.

What the “Shahīd” complex is all about is revealed to us by a pardah’khān, a Persian storyteller in front of a large screen display in the tradition of Persian coffeehouse painting: The protagonist inherited the name Shahīd from her great-grandfather Mirza Ghulām Husayn Tihrānī, who died for his beliefs during the constitutional revolution in Iran in 1907 and was awarded the honorary title of “martyr” (shahīd).36At the end of her autofictional research, Nargis discovers that she was on the wrong track and that she inherited the name from her great-grandmother—the true martyr who had no right to be in the public sphere. Even in the diaspora in Munich, the protagonist finds herself surrounded, pursued by the society of martyrs, who, as glorious spirits of patriarchy, shadows of the past, and tentacles of an expanded nation, want to prevent her from changing her name. A recurring shot shows Nargis/Bahārak lying naked on the ground, surrounded and literally crushed by men in black clothing. In another scene, her white-clad body becomes a screen and projection surface for archive images of the 1979 Revolution. The (de)colonization of the female body is a leitmotif in diasporic cinema.37Mania Akbari’s How dare you have such a rubbish wish? (2022) also deals with the colonization of the female body. Using around a hundred film clips taken from popular, pre-revolutionary cinema (fīlmfārsī), the so-called “years of sexual freedom” before 1979 are presented as a story of female bodies penetrated and marked by male gazes, which divided women into “chaste” and “unchaste” dolls. From this perspective, the revolution of 1979 does not appear as a rupture with the dichotomy chaste/unchaste, but as a mere reversal: the codes of chastity began to dominate the public space, while the spectacle of the “unchaste dolls” was made invisible, in other words: banished to the private sphere. After all, the body can be screened in a completely different form in the diasporic film spaces than in official cinema in Iran, which is subject to the rules of gaze (ahkām-i nigāh kardan), the semiotics of the hijab, and Islamic mise-en-scène. Or, to put it another way: diasporic film spaces and films from Iran are not subject to the same censorship.

Anti-Martyrocracy

The crossing out of the martyr’s name in Kalhur’s Shahid gains enormous complexity when seen in relation to the concerns of the Jīnā Movement, and with that, I would like to return to the starting point of this article. The feminist liberation movement has not only pushed the masculinist cult of state martyrdom into the background. Even the dissident reappropriation of the concept of martyrdom has lost its popularity. In contrast to the Green Movement (2009), martyrdom is no longer used so often as an interpretative framework to mourn the victims of resistance as heroines. As stated at the beginning: The movement would rather live than die “in the name of” (God, Holy Defence, Islamic Revolution).

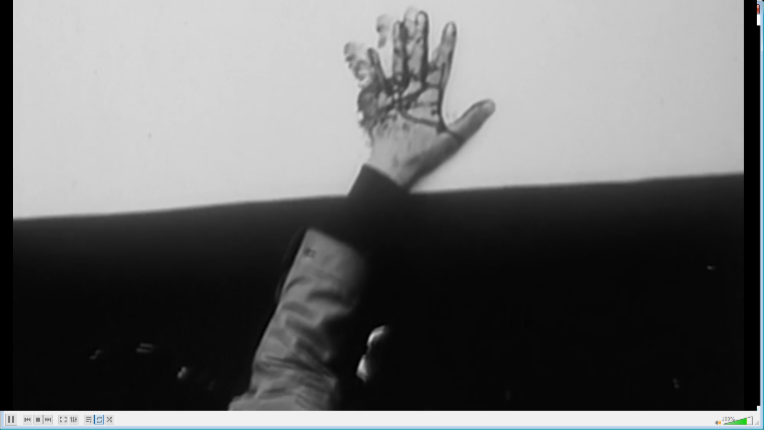

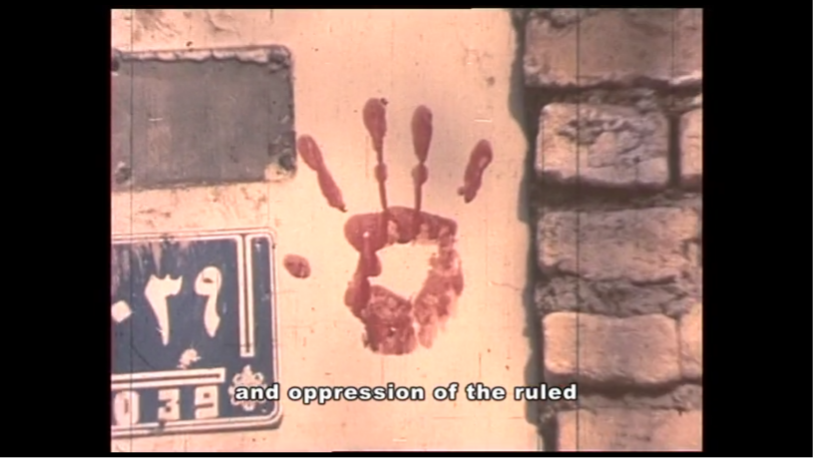

During the “Jin, Jiyan, Azadî”-movement, many state symbols of martyrdom have been replaced by revolutionary signs that, throughout history, stubbornly resisted being co-opted by the Islamic Republic’s visual propaganda machinery. Remarkably, a lot of blood-red hands (and hand prints) were brought into play and displayed, particularly prominently by protesting art students of Azad University Tehran on 9 October 2022, or online, as memes, after security forces attacked students staging a sit-in at Sharif University on 2 October 2022.

|

|

Figure 21: Blood Red Protest Hands, Sharif University and Azad University Tehran, October 2022.

It is important to keep in mind that the blood-red hand (print) has been a strong sign and gesture of first-hand witnessing throughout history. We can trace the “microhistory”38Cf. Carlo Ginzburg, “Microhistory: Two or Three Things That I Know About It,” Critical Inquiry 20, no. 1 (1993): 10–35. of this—also transculturally significant—sign of resistance and decolonization not only back to the street protests in Tehran around the Revolution 1979 (and to the ways it is well documented by numerous films and photographs), but even further back, to the popular cinema before 1979: At the end of Mas‘ūd Kīmiyā’ī’s film Reza Motorcyclist (Rizā Muturī, 1970), when Rizā (Bihrūz Vusūqī) is stabbed in a movie theatre, he leaves a memorable, indexical and iconic trace: a bloody handprint on the inner diegetic cinema screen—as if to pass on his blood testimony to the cinema audience, and turn them into witnesses. A comparable symbolism can also be found in the film at the beginning of Mas‘ūd Kīmiyā’ī’s The Deer (Gavazn-hā, 1974), when Qudrat (Farāmarz Qarībiyān) is on the run from the police with a gunshot wound and a bag full of stolen money, he wipes his bloodstained hand on a house wall as if to leave a public trace of blood testimony.39Cf. Matthias Wittmann, “Ciné-Martyrographies. Media Techniques of Witnessing in Iranian Cinema,” British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies (BRJMES), Special Issue: Cultural Production, Propagandas, and Negotiating Ideology in Iran, ed. by Goulia Ghardashkhani, Olmo Gölz und Kevin Schwartz (2024), accessed September 2025, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13530194.2024.2342178.

Figures 22-23: Screen grabs from Reza Motorcyclist (Rizā Muturi), directed by Mas‘ūd Kīmiyā’ī, 1970.

Figures 24-26: Screen grabs from Conversation with the Revolution (Guftugū bā inqilāb), directed by Robert Safarian, 2011.

As a body politics that remembers injustice, the iconic, symbolic and indexical sign of the blood-red hand re-appeared in different times and movements (The Green Movement 2009, Jin, Jiyan, Azadî 2022), and persistently eluded complete integration into the iconography of state martyrdom40In stark contrast to numerous symbols derived from Persian poetry, Sufi mysticism, and Islamic imaginaries (such as tulips, roses, candles, birds like doves, butterflies and moths) that were increasingly incorporated by the iconography of the IRI. with its disembodied, abstract martyr symbols. Especially the reclaiming of bodily autonomy during the “Jin, Jiyan, Azadî”-movement went hand in hand with attempts to challenge the necropolitical state doctrine of self-sacrifice in the name of sacred defence. The blood-red hand is an expression of this challenge. Instead of bearing witness to the achievements of the martyr’s welfare state, the symbolism of the blood-red hand testifies to its injustice.

Similar to the microhistory of the red hand, the history of feminist film in Iran also provided an archive of resistant counter-images to the disembodied, abstract martyr symbols produced by the necropolitical rhetoric of the state. Women were anything but mere victims, but central agents, architects, and forces of the historical processes in Iran. Cinematic practices became important constituents of this agency, especially when it came to counter-witnessing “resistant subjectivities”41Howard Caygill, On Resistance. A Philosophy of Defiance (London/New York: Bloomsbury, 2013), 97ff. that had (and still have) no right to be remembered by the visual machinery of the martyrocracy and its “clerico-engineers.”42Mohamad Tavakoli-Targhi, “The Emergence of Clerico-Engineering as a Form of Governance in Iran,” Iran Nameh 27, nos. 2–3 (2012): 14f.

As has been shown, the popular memory of resistance in Iran would be inconceivable without a long, multi-layered history of feminist film practices of (self-)image production and the facilitation of solidarity between generations and classes, including the depiction of subaltern forms of articulating a revolutionary, emancipatory consciousness. According to Michel Foucault (in a conversation with Pascal Bonitzer in 1974), “memory is an important factor in struggle, […] if you hold people’s memory, you hold their dynamism. And you also hold their experience, their knowledge of previous struggles. You make sure that they no longer know what the Resistance was actually about…”43Pascal Bonitzer and Serge Toubiana, “‘Anti-Rétro’ – Michel Foucault in interview,” Cahiers du cinéma 251-252 (July- August 1974), accessed September 2025, https://onscenes.weebly.com/film/anti-retro-michel-foucault-in-interview. — The people of Iran very well know what “resistance was [and is] actually about.”44Pascal Bonitzer and Serge Toubiana, “‘Anti-Rétro’ – Michel Foucault in interview,” Cahiers du cinéma 251-252 (July- August 1974), accessed September 2025, https://onscenes.weebly.com/film/anti-retro-michel-foucault-in-interview. The revolutionary imaginary in the midst of social life in Iran remains so resilient not least because it is interwoven with a strong cinematic memory of women’s struggle against the colonization of their bodies.

Cite this article

This article examines the feminist cinematic practices and aesthetics of liberation developed by Iranian women filmmakers from the 1979 Revolution to the present, showing how their work challenges the necropolitical cult of martyrdom and the state’s self-sacrificial ideology. Taking Éric Vuillard’s statement that “martyrdom is a trap for the oppressed” as its guiding motif, it explores how filmmakers such as Rakhshān Banī-i‘timād, Tahmīnah Mīlānī, Manīzhah Hikmat, Mahnāz Afzalī, Sahar Salahshūr, Mīnā Kishāvarz, and Nargis Kalhur have developed resistant forms of cinematic “counter-witnessing.” Their films expose the contradictions between revolutionary promises and social realities, revealing how women’s struggle against the colonization of their bodies became a collective movement for life rather than for sacrificial death. By analyzing these filmmakers’ tactics—from documentary realism to collective and auto-ethnographic filmmaking—the article argues that Iranian feminist cinema creates transgenerational and class-transgressive solidarities that reclaim the right to appear, to speak, and above all, to live beyond the confines of martyrdom.