Gendered Space in Abbas Kiarostami’s Early Cinema

Introduction

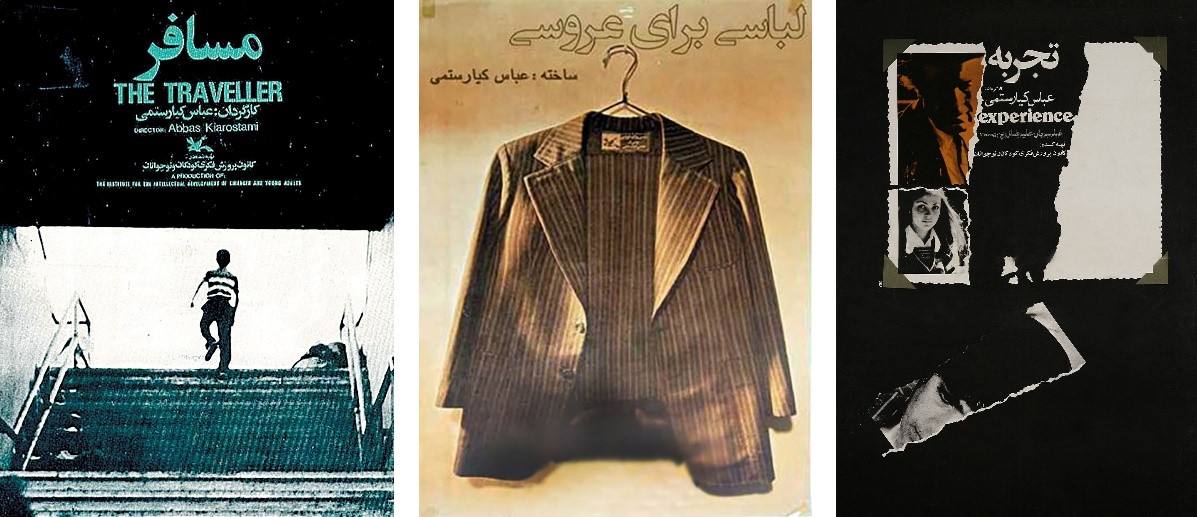

This article examines the early cinematographic works of ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī (1940-2016), spotlighting the intricate nexus between childhood, education, and spatial dynamics in the context of 1970s pre-revolutionary Iran. Through a detailed analysis of three seminal films—The Experience (1973), The Traveler (1974), and A Wedding Suit (1976)—we employ Henri Lefebvre’s and Robert Tally’s spatial theories to dissect the multifaceted spatio-temporal dimensions Kīyārustamī navigates. Initially, we explore The Significance of Kīyārustamī’s Early Trilogy, highlighting how these works not only reflect but also critique the societal and urban transformations of the era, particularly through the lens of marginal childhoods and inter-provincial migration experience. Subsequently, our discussion pivots to the Theoretical Framework: Cinematic Cartography and the Production of (Urban) Space, setting the conceptual groundwork for interpreting Kīyārustamī’s spatial representations. Analyses of individual films then follow, beginning with The Experience (a deep dive into urban repression, the body, and sexuality), moving to The Traveler (which examines institutional influences on the individual, specifically through nuclear family and education systems), and concluding with A Wedding Suit (which focuses on child labor as an embodiment of socioeconomic strife). The conclusion synthesizes these insights, emphasizing Kīyārustamī’s critique of everyday life and the persistent relevance of his films in illuminating the gendered, class, and spatial dimensions of Iranian society during a pivotal historical juncture. Through this examination, Kīyārustamī’s trilogy emerges not only as a cinematic exploration of space and identity but also as a poignant commentary on the evolving socio-political landscape of Iran.

Figure 1 (from left): Poster for the film Musāfir (The Traveler, 1974), Libāsī barāyi ‛arūsī (A Wedding Suit, 1976), and Tajrubah (The Experience, 1973), directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī.

The Significance of Kīyārustamī’s Early Trilogy: The Experience, The Traveler, and A Wedding Suit

‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, an Iranian filmmaker, screenwriter, editor, photographer, graphic designer, and painter, made a significant impact in the realm of cinema, actively engaging in filmmaking since the 1970s.1This text is an adapted version of a manuscript presented by the authors at a virtual conference held in May 2021 at Texas State University conducted online under the auspices of Robert T. Tally Jr. Farideh Shahriari and Aidin Torkameh. “Production of Gendered/Racial/Class Space: Abbas Kiarostami’s Cinema in 1970s Iran” in The Spatial Imagination in the Humanities, Section: Spaces of a World System, Texas State University, May 21, 2021. His prolific career includes a diverse repertoire of over forty films, encompassing both feature-length works and short films, as well as documentaries. Internationally recognized as the most prominent Iranian filmmaker, Kīyārustamī is closely associated with renowned works such as Close-Up (1990) and The Koker Trilogy (1994-1996) within the Iranian context, while his global audience predominantly acknowledges his later films, including Dah (Ten, 2002), Ta‛m-i Gīlās (Taste of Cherry, 1997), Shīrīn (2008), Certified Copy (2010), and Like Someone in Love (2012). Despite this, Kīyārustamī’s early cinema remains largely overlooked and underexplored. Paradoxically, the filmmaker himself attested to the profound influence of his documentary works and early films on shaping the sophisticated narrative framework that characterizes his later cinematic achievements.

In particular, Kīyārustamī highlighted the seminal importance of his debut film, the short feature Nān va Kūchah (Bread and Alley, 1969), which served as a cornerstone for his subsequent artistic endeavors.2“Abbas Kiarostami in Conversation with TIFF Director & CEO Piers Handling,” YouTube, March 10, 2016, accessed 04/09/2024, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-1CCPg5UY-E. Moreover, his early films explicitly addressed numerous social, political, and economic issues, reflecting a deep engagement with the prevailing concerns of the time. Towards the end of the 1960s, Kīyārustamī was commissioned by the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults to create educational documentaries specifically tailored for a younger audience. These formative works introduced and explored key thematic elements that would become integral to his future filmography, including childhood, masculinity, education, bodies, and, notably, space and urbanization. Despite the significance of these themes, the intricate relationship between space and urbanization in Kīyārustamī’s early cinema has regrettably received limited scholarly attention.

In Kīyārustamī’s early films, there is a notable emphasis on children, education, and urban space. This thematic engagement persists in his subsequent works, where glimpses of the problem of education and children can still be observed. For instance, one could interpret the impetus behind the production of Hamshahrī (Fellow Citizen, 1983) as rooted in the matter of childhood education, which had previously been visualized in works such as Bi tartīb yā bidūn-i tartīb (The Orderly or Disorderly, 1982) and Hamsurāyān (The Chorus, 1982). In other words, it appears that one of Kīyārustamī’s approaches is to explore how school education can potentially lead to a tragedy on a city-wide scale, as depicted in Fellow Citizen. Consequently, Kīyārustamī himself emphasizes, “I don’t consider myself in any way as a director who makes films for children. I’ve only shot one film for children; all the rest are about children.”3Alberto Elena, The Cinema of Abbas Kiarostami (London: Saqi, 2005), 33. Emphasis added.

This article aims to provide a spatial reading of Kīyārustamī’s three early films. Kīyārustamī was one of the few filmmakers who actively engaged with the intertwined issues of childhood, education, and space during the 1970s. By examining his early experimental films, namely Tajribah (The Experience), Musāfir (The Traveler), and Libāsī barāyi ‛arūsī (A Wedding Suit), this article seeks to explore and highlight some of the fundamental social mechanisms in the spatial organization of Iran through planetary urbanization on the eve of the Islamic Revolution in 1979. Planetary urbanization challenges the traditional notion of urban studies, which differentiated between urban and non-urban spaces. The concept suggests that the form of urbanization has dramatically evolved, rendering these distinctions obsolete and highlighting that even areas far removed from conventional urban centers are part of a global urban fabric.4See Henri Lefebvre and Robert Bononno, The Urban Revolution (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003) and Neil Brenner, Implosions/Explosions: Towards a Study of Planetary Urbanization (Berlin: JOVIS, 2014).

In analyzing the cinematic progression of Kīyārustamī, a compelling argument can be made that his three early films collectively form an early trilogy, distinguished for their thematic concentration on urban experience. Contrasting this early trilogy with The Koker Trilogy (Kīyārustamī’s later, well-known trilogy), reveals a significant alteration in Kīyārustamī’s directorial focus and narrative style. The early films serve as a foundational trilogy, laying the groundwork for Kīyārustamī ’s exploration of urban landscapes and issues, which contrasts with the rural backdrop and themes prevalent in The Koker Trilogy. This comparison highlights the refocusing of Kīyārustamī’s filmography, showcasing his versatility in addressing diverse settings and societal issues through a cinematic lens. The Koker Trilogy and the director’s earlier films present contrasting thematic explorations, yet both are deeply rooted in the socio-cultural fabric of Iran.

The Koker Trilogy primarily delves into the experiences of young men in rural settings, emphasizing a spiritual journey that intertwines the director’s artistic vision with his characters’ search for self-definition. These narratives are introspective, focusing on personal and spiritual growth within rural landscapes. In contrast, the director’s early films pivot to the urban experience, confronting more tangible socio-economic challenges. These three films address critical issues such as child labor, sexual repression, the complexities of migration, and the overarching influence of internationalized capitalism on daily life. This shift from urban to rural, and from concrete socio-economic struggles to spiritual narratives, marks a significant thematic transition in the director’s work. The three earlier films, when viewed collectively, offer a spatial perspective on child labor as a consequence of rapid urbanization in 1970s Iran. This period, under the rule of Muhammad Reza Pahlavi, was marked by significant transformations including the dramatic increase in oil revenues and the subsequent state investment in urban development, particularly in the real estate sector. The films reflect the impact of these changes on the lives of children and the working class.

This article argues that this urban perspective (particularly when juxtaposed with the rural focus of The Koker Trilogy), presents a comprehensive cinematic exploration of Iran’s evolving landscape during this era. In this context, we argue that Kīyārustamī’s films offer insights into how planetary urbanization influenced Iranian socio-spatial dynamics, blurring the lines between urban and non-urban spaces and reflecting a worldwide urban condition where political and economic relations are deeply intertwined.

Theoretical Framework: Cinematic Cartography and the Production of (Urban) Space

This article follows Robert Tally’s insights on literary cartography to read Kīyārustamī’s films as literary works that represent a specific space within a cinematic cartography. As Tally suggests in an interview with Amanda Myer, literary cartography helps us see how an author (auteur) produces something akin to a literary map.5Amanda Meyer, “A Place You Can Give a Name To: An Interview with Dr. Robert T. Tally Jr.,” Newfound: An Inquiry of Place 4 (Winter 2012), https://newfound.org/archives/volume-4/issue-1/interview-robert-tally/. According to Tally,

Narrative itself is a form of mapping, organizing the data of life into recognizable patterns with it understood that the result is a fiction, a mere representation of space and place, whose function is to help the viewer or mapmaker, like the reader or writer, make sense of the world. In Maps of the Imagination, Peter Turchi asserts that all writing is in one way or another cartographic, but that storytelling is an essential form of mapping, of orienting oneself and one’s readers in space.6Robert T. Tally, Spatiality (London: Routledge, 2013), 46.

Furthermore, drawing on Henri Lefebvre’s ideas of the production of space, planetary urbanization, and critique of everyday life, we aim to explore the key spatio-temporalities of Iran, particularly Tehran, during the 1970s as manifested in everyday life. Kīyārustamī’s films are here explored as a representation of the everyday lives of working-class male child laborers—some who have migrated from the provincial peripheries—who live in the outskirts of Tehran. Our argument is that Kīyārustamī’s cinema maps the class and gendered nature of the production of space as experienced by the main male adolescent characters in his films. All three protagonists endure the same forms of oppression and marginalization that simultaneously have conceptual and physical dimensions.

Thus, this article posits the cinematic and spatial representation of Tehran in Kīyārustamī’s cinema as a geocritical cartography. Kīyārustamī precisely positions his camera at the liminal space and time where the systematic mechanisms of producing suppressed and tamed bodies are situated within the broader context of urbanizing Iran during the 1970s. More specifically, Kīyārustamī’s camera was able to highlight events and structures that were unfolding during a crucial period in contemporary history. It can be argued that a spectrum of multi-scalar and multi-rhythmic spatio-temporalities was emerging in Iran during that era, and this spectrum is either explicitly reflected in Kīyārustamī’s films or implicitly present in the background. These spatio-temporalities include the imposed destruction of peasant and non-capitalist agricultural modes of life, proletarianization, and subsequently, rural-to-urban migration and the emergence of informal settlements and precarity.

One of the key contributions of Lefebvre to Marxism and radical geography is the concept of the production of space as a triadic dialectical process encompassing social, physical, and conceptual moments. Social production of space entails both the social production of nature/environment and the representation of space. However, the crucial point in the dialectics of spatial production is that neither nature/environment nor mentality/conception should be considered as the starting point of analysis, rather, it is the social that should be considered as the starting point. Through the concept of the production of space, Lefebvre was able to transcend both crude materialism (which posits nature and physical environment as the starting point of analysis) and transcendental idealism (which places idea as the basis). Furthermore, as can be inferred from Lefebvre’s notion of the production of space, the state in its integral/extended sense emerges as the primary force of the production of space. The production of space, in this sense, is largely caused by state intervention aimed at organizing and destructing social life through the production of “abstract space”—the specialized/elite representations of space by the state—as the condition for the reproduction of the state itself. Therefore, one can say that this state-centric mode of production of space results in an abstract space that disrupts everyday life and alienates individuals. This article conceives urban space as a fusion of multiple social forms that interact with each other. In the following discussion, some of these fundamental social forms, such as center-periphery relationships, homelessness, and child labor are examined in ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī’s cinema.

The Experience (1973): Urban Experience as the Repression of the Body and Sexuality

The multidimensional narrative of The Experience revolves around the everyday life of Mamad, a young teenager, who, when unable to sleep at his workplace as an errand boy, is practically forced to live on the streets.7‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, dir. The Experience [Tajribah] (Tehran, Iran: Kānūn Parvarish-i Fikrī, 1973). Kīyārustamī endeavors to use his camera to capture different hidden corners of Tehran, shedding a clearer light on the life of child laborers in 1970s Iran. The Experience signifies a personal and fundamentally urban experience of the workspace. This film provides us with a framework through which we can examine the Iranian experience of urban capitalist modernity. The Experience portrays the new urban form of alienation, evident in the absolute emotional indifference of Mamad’s employer towards him combined with torturous and threatening behavior. Moreover, the dwelling here is nothing more than a miserable refuge within the workspace (figure 2). Consequently, the urban experience for Mamad turns out to be an experience of being erased from social space, where he is essentially invisible and unheard. His plight is further compounded by lack of education.

Figure 2: A still from Tajribah (The Experience, 1973). ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, accessed via https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x3pg2gy (00:00:03)

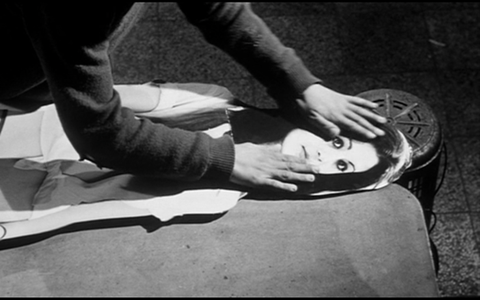

The film also represents a new form of sexual experience that has arisen alongside the emerging form of urbanization. In his initial forays into urban environments, Mamad, embodying the typical yearnings of adolescence, exhibits a pronounced interest in the opposite sex. This is evident in the way he attentively observes and subtly follows girls, utilizing both visual attention and physical movement, as he navigates the streets. This new space has provided him with new possibilities for sexual pleasure. In another scene, Mamad is expelled from the shop where he works for sticking a picture of a girl he likes onto the face of a cardboard cut-out of a model (figure 3). Consequently, it appears that any bodily experience for Mamad is accompanied by punishment or torture. Perhaps for this reason, Kīyārustamī often portrays Mamad in tight, confined, and dark frames, with broken and opaque mirrors, symbolizing a form of enforced bodily confinement (figures 4-7). The urban space, which was seemingly supposed to offer new possibilities for bodily pleasures and diverse experiences, has become a restrictive and oppressive space.

Figure 3: A still from Tajribah (The Experience, 1973). ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, accessed via https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x3pg2gy (00:00:05)

Figure 4: A still from Tajribah (The Experience, 1973). ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, accessed via https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x3pg2gy (00:18:10)

Figure 5: A still from Tajribah (The Experience, 1973). ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, accessed via https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x3pg2gy (00:41:38)

Figure 6: A still from Tajribah (The Experience, 1973). ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, accessed via https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x3pg2gy (00:19:42)

Figure 7: A still from Tajribah (The Experience, 1973). ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, accessed via https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x3pg2gy (00:41:32)

Mamad’s brother’s house also serves as a key location within the film where another aspect of sexual repression is manifested. The house is essentially nothing more than a small room. As such, when a third person (Mamad) is present, the cramped domestic space does not allow Mamad’s brother and his wife to engage in sexual relations. The film illustrates this skillfully, thus subtly showing how spatial limitations can contribute to the reproduction of sexually repressed/docile bodies.

Additionally, The Experience poignantly addresses urbanized class contradictions. A striking visual motif throughout the film is the juxtaposition of Mamad—engaged in assigned responsibilities such as shining shoes—beside affluent figures, exemplified in one scene by a well-dressed, middle-aged man absorbed in his newspaper. Here, we see that Mamad’s socks and shoes are worn out and tattered (figure 8), and instead of being engaged in studying or playing at his age, he roams around aimlessly, striving only to survive. However, survival for him is only possible by submitting himself entirely to the intense exploitation and suppression by the employer, his family (brother), and the broader urban environment.

Figure 8: A still from Tajribah (The Experience, 1973). ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, accessed via https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x3pg2gy (00:44:38)

Mamad is not the only child laborer in this film. Kīyārustamī repeatedly explores the interactions of child laborers and how they seemingly exist in a realm disconnected from the real world. This representation of an increasingly pervasive market economy in Iranian experience—evident in the living and working spaces, and the relationships between them—implicitly supports what Lefebvre conceptualizes as planetary urbanization, a new condition permeating all geographical scales. The class confrontation scene—during the shoe-shining episode in which Mamad sits beside a wealthy old man, clad in lavish suit and shoes, his own clothes threadbare and torn—reveals the hierarchical nature of planetary urbanization, which was gradually emerging in 1970s Iran. Kīyārustamī’s film, at a deeper level, confronts us with the interlinked rhythms of wage labor and the expropriation of space. This process signifies a new experience of space-time that is partly the result of the imposition of broader structural forces, such as proletarianization, within the context of planetary urbanization. These structural forces tend to destroy or internalize non-capitalist forms of production. In 1970s Iran that included a range of subsistent modes of life such as traditional agriculture, animal husbandry, and other local industries.

Kīyārustamī’s cinematic narrative techniques, as seen through the lens of geocriticism and the insights of Robert Tally in his book Spatiality, offer a profound exploration of the spatial dynamics shaping our contemporary world.8Robert T. Tally, Spatiality (London: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, 2013), 113. Kīyārustamī’s portrayal of urban spaces, particularly within the class-structured and patriarchal context of Iranian society, resonates deeply with the geocentered approach of geocriticism, as defined by Bertrand Westphal.9Bertrand Westphal, Geocriticism: Real and Fictional Spaces, trans. Robert T. Tally (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), x, 6, 112, 113. This approach emphasizes the intricate interplay between literature, or in this case, film, and the real world, with a specific emphasis on the significance of place and space. Tally’s insights further illuminate this approach, suggesting that geocriticism encompasses both aesthetics and politics, serving as a tool for understanding the complex spatial relationships that define our contemporary world. He argues that a key task of geocriticism is to analyze, explore, and theorize new cartographies that help make sense of our places and spaces. These cartographies include not only geographical mapping but also the production of knowledge through various disciplines which can be used for both repressive and liberatory purposes.

The centrality of the urban experience in these films is also evident in the way Kīyārustamī focuses on urban rhythms and specifically the sound of the urban environment as a narrative technique. In Kīyārustamī ’s early cinema, particularly evident in The Experience, the absence of music is a deliberate choice to immerse the audience in an authentic urban soundscape. This approach aligns with Westphal’s concept of polysensoriality in geocriticism, extending the sensory experience of space beyond the visual to the auditory. Kīyārustamī utilizes diegetic sound, encompassing the voices of actors, ambient urban noises like car sounds, and the general auditory milieu of the city, to craft a distinctive narrative feature. The Experience, noted for its minimal dialogue, allows the diegetic sound to take precedence, effectively placing the urban space at the forefront of the storytelling. This technique shifts the narrative focus from the human characters to the spaces they inhabit, essentially narrating the places themselves. This cinematic strategy resonates with R. Murray Schafer’s influential work on soundscapes, which underscores the importance of sound in shaping our perception of space, thereby contributing to a richer geography of the senses.10Raymond Murray Schafer, The Tuning of the World: Toward a Theory of Soundscape Design (New York: Random House, 1977), 53. John Douglas Porteous’s notion of an allscape encapsulates this multisensory world, suggesting that our interaction with, and comprehension of, space results from a complex interplay of sensory inputs.11John Douglas Porteous, Landscapes of the Mind: Worlds of Sense and Metaphor (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1990), 6. Kīyārustamī’s films, through their focus on the auditory elements of urban environments, exemplify this polysensorial approach. They demonstrate how sound, alongside other senses, plays a crucial role in constructing our spatial understanding and experiences, thus offering a multisensory experience of the world.12Bertrand Westphal, Geocriticism: Real and Fictional Spaces, 133.

The transformation of Mamad’s character in Kīyārustamī’s film exemplifies a geocritical perspective. Initially, Mamad is shown in conditions of darkness and fragmentation, enduring humiliation for the sake of shelter. This journey from darkness to light is not just a narrative arc but a socio-spatial process, reflecting the reciprocal creation of space that is central to geocriticism. Kīyārustamī’s film, therefore, presents a collective representation of urban life, informed by diverse perspectives. This aligns with Tally’s view of geocriticism as a means to uncover hidden power relations in spaces. By focusing on the spatial aspects of Kīyārustamī’s narratives, one can appreciate that he offers a nuanced understanding of urban environments, revealing the complex interplay of social, political, and spatial factors that shape the individual and collective experiences of youth during the 1970s.

The Traveler (1974): The Nuclear Family and the School System as the Torturers of Bodies

The film The Traveler begins with a scene in which children are playing football in a dead-end alley (figure 9).13‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, dir. The Traveler [Mussāfir] (Malāyir, Iran: Kānūn Parvarish-i Fikrī, 1974. The alley is the only space where lower-class children and adolescents can spend their leisure time playing together. The main character of the film is Qāsim, a 12-year-old boy passionate about football, who lives in the small town of Malāyir,14A city and capital of Malāyir County in Hamadan Province, Iran. a peripheralized space by virture of its distance from the urban center of Tehran. The notion of peripheralized spaces draws on Lefebvre’s conception of colonization which is not limited to a convential understanding of the term. Stefan Kipfer and Kanishka Goonewardena analyze how Lefebvre’s concept of colonization evolved from his critique of everyday life to his work on the state. According to Kipfer and Goonewardena, Lefebvre views colonization as multi-scalar strategies for organizing territorial relations of domination.15Stefan Kipfer and Kanishka Goonewardena, “Urban Marxism and the Post-colonial Question: Henri Lefebvre and ‘Colonisation’,” Historical Materialism 21, no. 2 (2013): 1-41. He defines it as a state-specific method of organizing hierarchical territorial relations or as a state strategy for producing space. Critiquing Rosa Luxemburg, Lefebvre argues that she overlooks the center-periphery relationship in both capitalist and non-capitalist regions, focusing only on non-capitalist peripheries. Lefebvre insists on including internal colonization, which is a domination relationship between a center and a periphery, in analyses of colonization. He posits that colonization occurs when political power ties a territory and its productive activities or functions to a subordinate social group, thereby organizing both domination and production. According to Lefebvre, colonization is an integral part of the state’s role in reproducing relations of production and domination.

Figure 9: A still from Musāfir (The Traveler, 1974). ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pDImZ5Q8Bfo (00:03:00)

Qāsim’s urban experience here is not confined to the colonial relationship between his hometown and Tehran. This coloniality intersects with another hierarichal spatial relation as embodied in the nuclear family space. The familial space is embued with gendered relations as well. This is manfested in a scene where Qāsim strives to skip school in order to play football. This space of play ultimately gives way to the disciplinary, intimidating, and militaristic space of education. In an intermediate scene between the space of play and the space of education, we observe the nuclear family space, which seemingly appears as a monotonous feminine space due to the physical absence of the father. However, Kīyārustamī’s lens implicitly shows that this femininity is nothing more than the Other of masculinity, and therefore does not reflect any traces of an alternative femininity as a radical difference from masculinity.16Gillian Rose, Feminism and Geography: The Limits of Geographical Knowledge (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1993), 126, 142, 147, 243-244, 268, 272. This can be seen in the confrontation between the mother and the son when the son steals money from his mother and despite her pleas, the father won’t punish the son, possibly due to being tired, addicted, or other issues. This leads the mother to take on the traditional role of the father herself and perpetuate the disciplinary and oppressive function within the family.

Qāsim is subjected to a multiplicity of state-imposed spatial mechanisms, across the school and home, aimed at producing docile bodies through disciplinary procedures. Qāsim’s sleeping space in his home is more akin to a prison cell than a bedroom. His illiterate mother constantly belittles him, and Qāsim is transformed into a skilled and organic liar in such an environment. Interestingly, in all Kīyārustamī’s films from the early decade of his filmmaking career (and in his experimental films in particular), the figure of the mother is portrayed as an abhorrent and malevolent character. In one scene of The Traveler, we witness the mother engaged in a dialogue with Qāsim’s grandmother as she struggles to handle Qāsim and his mischievous games. The mother informs the grandmother that Qāsim is not focusing on his studies. Consequently, the grandmother firmly suggests that Qāsim should be withdrawn from school to start working instead. It is as if the alternative to studying in such an environment is simply being transformed into a child laborer—a common denominator in Kīyārustamī’s early trilogy. In this scene, the frustrated mother, due to Qāsim’s playfulness, conspires with the grandmother to report Qāsim’s misconduct to a male authority figure, namely the school principal (and thus the state), in order to consider appropriate punishment for him. In another related scene, we also see the image of Mohammad Reza Shah on the cover of a textbook, which serves as a reflection of the omnipresence of the state, enabled by a homogenized, centralized, monolingual, and nationalistic educational system.

In another scene set in Qāsim’s school, one sees as the teacher, in a rather sneaky manner, tries to snatch the magazine that Qāsim is reading (figure 10). With cunning movements and maneuvers from behind, the teacher surprises him by swiftly reaching over the desks. The teacher then sits behind his own desk, content with his recent hunt, and starts to enjoy reading the magazine instead of teaching. In an environment where nothing happens except physical punishment, humiliation, snitching, and profanity, the educational space hardly differs from a prison.

Figure 10: A still from Musāfir (The Traveler, 1974). ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pDImZ5Q8Bfo (00:06:50)

In another scene, we witness Qāsim calculating the amount of money he needs for a trip to Tehran and to watch a football match at a stadium there. Meanwhile, the teacher, who himself is a wage laborer, is shown in class, calculating the installments he must pay at the end of the month. Symbolically, this depicts how both generations are indebted and living under a lot of financial pressure. When Qāsim steals money from his home to acquire a bus ticket for his trip to Tehran, his mother decides to report him to the school principal. In a particularly intense scene, the mother, driven by a desire for discipline and retribution, visits the school to report Qāsim for stealing money from her. She demands that the principal not only reprimand him but also physically punish and torture him to extract a confession. As this harrowing scenario unfolds, the mother positions herself in the corner of the office, observing the events with a cold-hearted detachment (figure 11). She waits, almost expectantly, for the confession to be coerced out of Qāsim under duress. The mother not only asks the principal to punish Qāsim but also becomes a spectator. The school principal represents the centralized state authority, a state that is the primary apparatus of oppression and the main agent in producing docile and tamed bodies. Furthermore, the principal himself is also a wage laborer. This scene starkly illustrates the intersection of personal grievances and institutional/state authority. The school principal, representing centralized state power, becomes an active agent in the production of submissive and controlled bodies, reflecting the broader societal mechanisms of oppression. The mother’s demand for punishment and her detached presence during the torture underscore the complexities and contradictions of familial and societal dynamics in disciplining and shaping individual behavior.

Figure 11: A still from Musāfir (The Traveler, 1974). ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pDImZ5Q8Bfo (00:19:48)

The film poignantly illustrates Qāsim’s arduous journey to Tehran, a journey that not only covers a physical distance of approximately 400 kilometers but also encapsulates the complex dynamics of the center-periphery relationship and the commodification of space in contemporary society. After enduring much suffering and hardship, Qāsim finally manages to reach Tehran—the center—in order to closely watch his favorite football match. What stands out here is the issue of the center-periphery relationship and the commodification of space. As the film depicts, the movement from small peripheralized towns to Tehran, which enables the experience of a relatively new spatio-temporal dimension (namely, intercity travel using public transportation), is costly. The problem is that not everyone can afford such an experience, and class inequalities become a major barrier to movement/mobility and the experience of new spacetimes. Consequently, the internally colonial relationship between the center and the periphery results in some individuals remaining physically and socially confined to previous spatio-temporal regimes, despite the existence of new spatio-temporalities.

In the final scenes of The Traveler, Kīyārustamī’s camera captures Qāsim as he searches for a ticket to the football match. After standing in line for a long time and failing to secure a ticket, he resorts to the black market, ultimately purchasing a ticket at a much higher price than he had anticipated. Now it is unclear how Qāsim will return to Malāyir as he no longer has any money for the return journey. Upon finding a place to sit in the stadium, he becomes so enthralled by the new spacetime that he quickly gets up to explore and wander around.

Qāsim’s movement within space here represents another aspect of urban experience portrayed in The Traveler, reminiscent of urban experience in The Experience. Qāsim, captivated and enthralled by the urban environment, becomes so immersed in his new environment that he eventually falls asleep in a corner, exhausted. What captivates Qāsim above all else is the possibilities that the urban centrality of Tehran affords him. It is this centrality that enables him to have new experiences, a centrality that signifies a qualitatively different spacetime from that of Malāyir. As becomes evident, it is not merely watching the football match that holds the greatest appeal for Qāsim. Instead, it is the experience of urban centrality in its entirety that has seized his attention and senses. His sleep is so deep that when he awakens, the football match has already ended. Moreover, even in his dreams, he is confronted with all the torture he has endured, illustrating how physical torture can negatively and perhaps permanently affect the mind.

Perhaps the most striking scene in Kīyārustamī’s experimental cinema is the final scene in The Traveler, where Qāsim is faced with a horrifying and dystopian image of a vast and empty stadium (figure 12). In this cinematic experience, the character is still standing amidst the ambiguity of light and darkness, representing the conflict between a space of subjugation and exploitation and a differential space. In The Traveler, Qāsim is lost in the empty space of the stadium, suspended between the allure of the centralized spacetime of Tehran and the suppression of the peripheralized spacetime of Malāyir. It is due to this thematic focus on urbanization and spacetime described at the beginning of the article that the three works The Experience, The Traveler, and A Wedding Suit form Kīyārustamī’s early trilogy. In other words, these three films all revolve around a central theme: urban experience.

Figure 12: A still from Musāfir (The Traveler, 1974). ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pDImZ5Q8Bfo (01:13:33)

A Wedding Suit (1976): Child Laborers as Embodiments of Socioeconomic Contradictions

Urban space and child labor form the common theme across all three works in Kīyārustamī’s early trilogy. It can be argued that in the process of capitalist urbanization and the unprecedented expansion of the wage labor form, employers in the 1970s strove to cover up some of the sudden difficulties arising from the onslaught of capitalist monetary relationships and surplus labor resulting from proletarianization by exploiting children. The final part of Kīyārustamī’s early trilogy, A Wedding Suit, depicts the story of three working teenagers who labor in various shops on different floors of a shopping center, or passage, in Tehran’s Grand Bazar.17‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, dir. A Wedding Suit [Libāsī Barāyi ‛Arūsī] (Tehran, Iran: Kānūn Parvarish-i Fikrī, 1976). The story revolves around three main characters named Mammad, ‛Alī, and Husayn. They are all adolescent boys whose bodies are systematically suppressed and made docile. In urban space they appear submissive and fearful in the presence of their employers and take revenge on each other for the hardships of daily life. The film begins with an opening scene featuring a large number of child laborers and their dark sleeping quarters. Each of these children has their own narrative, but they all share the experience of being child laborers.

Kīyārustamī’s depiction of Tehran in A Wedding Suit is a place both chaotic and vibrant, reflecting the tumultuous lives the characters lead. One particularly evocative scene shows three individuals on a three-wheeled motorcycle, their limbs jutting out, encapsulating the tumultuous energy of the city. The camera captures the urban landscape from diverse perspectives, reflecting the complexity of the environment these young men inhabit (figures 13-15). This urban environment functions as an unprecedented medium through which these young male labourers are able to experience bodily sensations. In A Wedding Suit, Kīyārustamī presents a striking shift in focus. This film centers on three male laborers who, unlike the characters in the first two films of his early trilogy, are not merely subjugated laborers of the system—they also emerge as rebels. These protagonists challenge the traditional power dynamics, opposing the adults who previously dominated them physically, emotionally, and mentally. They are portrayed as essential to the functioning of the capitalist system, which now appears to falter without their participation. These young men, displaying maladaptive adult behavior, navigate adult responsibilities and social norms. They engage in activities like dating, potentially active sexual relationships, and even resort to theft and blackmail, showcasing their resilience even when faced with violence.

Figure 13 (upper left): A still from Libāsī Barāyi ‛Arūsī (A Wedding Suit, 1976). ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vJc_MU9sJvg (: 00:00:34)

Figure 14 (lower left): A still from Libāsī Barāyi ‛Arūsī (A Wedding Suit, 1976). ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vJc_MU9sJvg (00:59:39)

Figure 15 (right): A still from Libāsī Barāyi ‛Arūsī (A Wedding Suit, 1976). ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vJc_MU9sJvg (00:02:14)

In their pursuit of masculine identities within a space marked by various forms of violence, the characters in the film exhibit behaviors that instill fear in others, embodying a systematic reproduction of masculinism. A significant narrative thread follows Mammad’s engagement in karate, symbolizing his aspiration for dominance and competitiveness. This is illustrated in his interactions with Ali, a tailor shop worker, and Husayn, both of whom are overpowered by Mammad’s intimidating presence and violent masculinity. This hierarchical dynamic reflects the trilogy’s overarching theme. Kīyārustamī draws a clear contrast between earlier representations of youth oppression and their later portrayal as assertive and independent. This shift marks a significant evolution in how young people and their place in Tehran’s socio-economic structure are depicted.

Although each of the three characters has their own story, Kīyārustamī’s camera focuses on Husayn and his bodily experiences. He showcases Husayn’s bodily exploitation in several different scenes, ranging from carrying heavy loads to performing delicate sewing stitches. When his employer attempts to shirk responsibility for paying him, Husayn only dares to make a request for payment once, and even then, he receives a violent verbal response from his employer filled with hostility. All child laborers are positioned as submissive servants and subjects under their employers, yet they exhibit rebellious behavior in various forms, often manifesting through acts of violence directed towards each other and their environment. It is likely that this surplus labor has played a key role in shaping Tehran’s market economy.18This article claims that the surplus labor present in Tehran has significantly influenced the shaping of the city’s market economy. However, there is a notable absence of concrete data to substantiate this assertion. Consequently, the authors identify the acquisition of empirical evidence in this area as a priority for future research endeavors.

In another meticulously crafted scene, the cinematic lens artfully captures the nuances of Husayn’s physical and sexual repression, intertwined with his covert infatuation for a girl. This complex sexual landscape is conveyed through a sequence of four distinct frames, each employing varying degrees of obstruction and concealment to illustrate the subtleties of Husayn’s unspoken desire and internal conflict. The scene opens with a wide shot, subtly hiding the details of Husayn’s vascular physique, hinting at his physical restraint. This is followed by a perspective shot from a window, where the girl is seen being asked out on a date, encapsulating the sexual nature of Husayn’s approach. The third frame captures stolen glances exchanged between Husayn and the girl amidst the backdrop of their workplace, a visual metaphor for their covert attraction and the barriers of their social environment. Finally, the scene culminates with Husayn’s renewed plea for a date, underscoring his persistent yet restrained pursuit (figures 16-19). The careful framing and shot composition not only enhance the narrative but also provide a deeper understanding of the characters’ rebellious tendencies and desires within the constraints of their social milieu.

Figure 16 (upper left): A still from Libāsī Barāyi ‛Arūsī (A Wedding Suit, 1976). ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vJc_MU9sJvg (: 00:14:06)

Figure 17 (upper right): A still from Libāsī Barāyi ‛Arūsī (A Wedding Suit, 1976). ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vJc_MU9sJvg (00:16:33)

Figure 18 (lower left): A stills from Libāsī Barāyi ‛Arūsī (A Wedding Suit, 1976). ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vJc_MU9sJvg (00:16:48)

Figure 19 (lower right): A still from Libāsī Barāyi ‛Arūsī (A Wedding Suit, 1976). ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vJc_MU9sJvg (00:17:03)

Furthermore, in the final image, Kīyārustamī attempts to highlight the distance and elusiveness between Husayn and his beloved girl using a distant and partially obscured view. This distance shapes a fundamental aspect of the characters’ connection insomuch as it must be expressed through largely hidden gestures to avoid drawing the attention of the observer’s gaze. As a result, essential elements of communication, such as physical proximity and verbal conversation, are withheld from both parties.

The story focuses on a suit being tailored for a customer by ‛Alī’s employer, which becomes the center of conflict when both Husayn and Mammad wish to borrow it for a night. This desire sparks a series of dramatic and complex events. After successfully convincing ‛Alī to lend him his suit, Husayn is caught under the stairs by Mammad. Here, Mammad is the embodiment of all the violence of which he himself is a product: from attempting to grope the girl accompanying Husayn, to bullying Husayn, taking off the suit and stealing his money. Employing a distant shot that captures the action beneath the stairs, Kīyārustamī ’s camera technique skillfully conveys a palpable sense of fear and uncertainty to the viewer about the potential outcomes in this confined space. This cinematographic choice not only heightens the tension but also underscores the transformation of these adolescents throughout the film. They evolve into figures who pose a threat not only to their immediate circle but also to the broader societal fabric, embodying roles of villains and rebels engaged in conflict with each other.

After Mammad departs from his peers to go see a film and a magic show. Meanwhile, Husayn and ‛Alī traverse the dark alleys of the market in search of Mammad to retrieve the suit. The camera fundamentally descends into darkness at moments, a technique that Kīyārustamī repeatedly employed in The Experience and The Traveler by alternating dark and bright frames. This sense of anxiety from searching and not finding, going and not reaching, is a recurring theme in all three films.

In a visually striking sequence, Husayn and ‛Alī meander through the labyrinthine expanse of Tehran’s bazaar, their journey taking them from one end to the other under the cloak of night. The scene culminates as they find themselves back at their workplace, a passage nestled within the bazaar’s intricate network. The film’s narrative then seamlessly transitions from the shrouded mysteries of the night to the stark realities of daylight. The audience is presented with a bird’s-eye view of the now deserted passage, a cinematic technique that not only provides a comprehensive visual perspective but also metaphorically elevates the viewers, positioning them as omniscient observers. This vantage point invites contemplation, posing the lingering question of whether Mammad will ever return (Figures 20-23). The answer is swiftly unveiled in a subsequent scene. Mammad’s re-entry into the passage marks a crucial narrative turn. He encounters his older brother, an unnamed proprietor of a nondescript store, and is promptly subjected to a physical reprimand. This moment of familial violence is emblematic of a perpetual cycle of masculine aggression. The physical punishment meted out by his brother mirrors the same brand of violent masculinity that Mammad himself had earlier imposed on Husayn and ‛Alī. This cyclical nature of violent masculinity, perpetuated from fathers to sons and from sons to their peers, is a critical thematic element. It underscores the deeply ingrained patterns of behavior that transcend individual actions, becoming a systemic issue. The film, through these sequences, not only narrates a story of interpersonal dynamics but also delves into a deeper societal commentary on the propagation of aggressive masculine norms.

In the tradition of The Experience and The Traveler, A Wedding Suit offers a profound exploration into the cultivation of docile beings, unveiling the intricate, hierarchical layers of subjugation through the poignant interplay among ‛Alī, Husayn, and Mammad. This cinematic journey reveals a stark transformation: the oppressed morph into oppressors, perpetuating a cyclical saga of repression. In this narrative, the once victimized emerge as architects of domination, illustrating the relentless cycle of subjection. A Wedding Suit not only captures the essence of human conflict but also serves as a powerful metaphor for the ceaseless production of subdued entities, where the line between victim and perpetrator blurs, and the cycle of oppression perpetuates ad infinitum.

Figure 20 (upper left): A still from Libāsī Barāyi ‛Arūsī (A Wedding Suit, 1976). ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vJc_MU9sJvg (00:36:18)

Figure 21 (upper right): A still from Libāsī Barāyi ‛Arūsī (A Wedding Suit, 1976). ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vJc_MU9sJvg (00:46:41)

Figure 22 (lower right): A still from Libāsī Barāyi ‛Arūsī (A Wedding Suit, 1976). ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vJc_MU9sJvg (00:47:46)

Figure 23 (lower left): A still from Libāsī Barāyi ‛Arūsī (A Wedding Suit, 1976). ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vJc_MU9sJvg (00:48:11)

Conclusion

All the main characters in the analyzed films in this essay live in their workplace. In fact, there is no mention of a separate residential place. The marketplace serves as both a workspace and a living space, and as a result, the concept of home is almost absent in these three films. Parents and other family members are also less present in the images, as if they never had a significant presence in the lives of these adolescents. This all suggests that structurally, during that era in Iran, “inhabiting” space in a Lefebvrean sense was fundamentally impossible for this class.19Mark Purcell, “Excavating Lefebvre: The Right to the City and its Urban Politics of the Inhabitants,” Geojournal 58 (2002): 99-108. To be more precise, these working children did not have the opportunity to use space. Their everyday lives were confined to the realm of monetary exchange. Lefebvre’s concept of the right to the city shifts the focus from traditional liberal-democratic enfranchisement to empowering inhabitants to directly influence all decisions related to the production of urban space. Central to this is the right to appropriation, which encompasses the inhabitants’ ability to access, occupy, and utilize urban space, thereby prioritizing their physical presence in city spaces. This right extends beyond merely occupying pre-existing spaces; it includes the right of inhabitants, regardless of nationality, to shape urban spaces according to their needs. Lefebvre envisions a paradigm where inhabitants, rather than capital or state elites, become the primary decision-makers in the production of urban space, ensuring their central and direct participation in shaping their living environments.20Mark Purcell, “Excavating Lefebvre,” 99-108.

Thus, Kīyārustamī’s cinematic oeuvre, particularly exemplified in three films from the 1970s, embodies what Lefebvre terms the critique of everyday life, by portraying the living spaces of children in specific Iranian locales. This narrative approach, recurring in works like Fellow Citizen (1983), serves as a vehicle for a Marxist critique of everyday life, highlighting the mundane yet significant aspects of human existence. One interesting aspect of Kīyārustamī’s works is that they remain highly relevant even after approximately five decades. The educational environment, the structure of the nuclear family, and, most importantly, the national state form has not undergone significant changes since the early 1970s. In a sense, they have been strengthened and consolidated. Therefore, Kīyārustamī’s cinematic narratives still resonate with our present condition.

Further, there are significant similarities in these three films that lie in the centrality of urban space. All the main characters in these three films, beyond their literal frames, exist within symbolic and metaphorical frames of broken windows, murky mirrors, and small and distorted confined spaces. In all these scenes, the viewer can perceive an image that is faded, shattered, and disillusioned within these frames. Thus, these limited, broken, and ambiguous frames can be seen as a representation of the repressive spatio-temporal regimes of Iranian society in the 1970s. Everyday life in Kīyārustamī’s films is the space of tamed and docile bodies.

Finally, Kīyārustamī’s distinct emphasis on masculinity underscores a notable omission: the absence of feminine and/or homosexual spaces. This portrayal of a monosexual, monovalent, homogeneous, and flat space serves as a prominent reflection of the masculine landscape in Iran during both the Pahlavi era and the Islamic Republic. This characteristic, prevalent in Kīyārustamī’s works, highlights the gendered dimension of space in these historical contexts (figures 24-26). Kīyārustamī’s films provide a profound understanding of the impact of planetary urbanization on Iranian socio-spatial dynamics. These films effectively blur the distinction between urban and non-urban spaces, mirroring a planetary urban condition wherein political and economic relations are intricately interwoven.

Figure 24 (left): Husayn’s close-up. Libāsī Barāyi ‛Arūsī (A Wedding Suit, 1976), ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vJc_MU9sJvg (00:32:38)

Figure 25 (upper right): Qāsim holding the camera. Musāfir (The Traveler, 1974), ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pDImZ5Q8Bfo (00:41:38)

Figure 26 (lower right): Mamad’s close-up in the mirror. Tajribah (The Experience, 1973). ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, accessed via https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x3pg2gy (00:33:03)

Cite this article

This article investigates ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī’s early films, including The Traveler and A Wedding Suit, through the lens of spatial theory and gender studies. It explores themes of childhood, education, and urbanization, focusing on how socio-spatial inequalities impact male child laborers in pre-revolutionary Iran. The article situates Kīyārustamī’s work within the socio-political transformations of the Pahlavi era, revealing how his cinematic cartography critiques modernization’s alienating and repressive effects, while offering a nuanced exploration of gendered experiences and socio-spatial dynamics.