From Hollywood to Tehran: American Movies in Iran Before the Revolution American Dreams in Iranian Theaters: Hollywood’s Rise Before 1979

Figure 1: A still from the film Vilgardān-i Sāhil (The Vagabonds of the Shore), directed by Gudratallāh Ihsānī, 1966.

Winter 1991. Tehran. The Fajr Film Festival.

On one of those bone-chilling February afternoons when your breath turns to ice before your words finish leaving your mouth, something magical—and slightly absurd—was happening at the Shahr-i Qissah cinema.

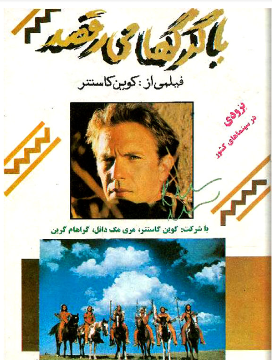

A massive crowd had gathered, bundled up like overstuffed cafés, forming a line that snaked around the block. Why? Because Dances with Wolves, Kevin Costner’s three-hour Western epic, was being screened. For the first time since the revolution, an American film was appearing on the big screen in Tehran—and not just any American film: one with buffalo stampedes, Lakota dialogue, and Kevin Costner bonding with a wolf.

This was cinema history, and no self-respecting cinephile was going to miss it—even if it meant standing in line so long that they could have filmed a movie about the line itself. Spoiler: many never even made it inside. The crowd was just too massive. Some were left pressing their noses to the glass like kids outside a candy shop.

Sensing a riot of film-hungry fans, the cinema owner—likely sweating bullets under his parka—announced a spontaneous midnight screening. Midnight! In Tehran! In winter! But people stayed. Some even cheered. That’s how desperate they were to see Kevin Costner ride across the prairies in slow motion. By the time the movie ended, groggy, awe-struck Tehranians stumbled out of the theater as the city’s early risers were heading to work. Confused commuters rubbed their eyes, wondering if they were hallucinating a crowd of people who looked like they had just time-traveled from the American frontier.

And thus, for one chilly, chaotic, unforgettable night, Dances with Wolves danced its way into Iranian cinema legend.

Figure 2. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Cinema Azadi and Cinema Shar Geseh occupied a central role in Tehran’s cinematic culture, functioning as the principal screening locations for the Fajr Film Festival during this period.

But what was the status of American cinema in Iran before the 1979 Revolution, during the era of the Shah? What kinds of Hollywood films were being screened in Iranian theaters? How did Iranian audiences respond to them? Who exactly was watching these films—which social classes, age groups, or cultural circles? Which movies were the most popular, and why did they resonate with local viewers? And beyond that, in what ways did American cinema impact the evolution of the Iranian film industry, including its screenwriting, direction, and acting techniques?

This article, in its own humble way, seeks to explore these questions and shed light on the cultural and cinematic exchange between the United States and Iran during the Pahlavī era: a time when Western pop culture played a significant role in shaping urban lifestyles and cinematic tastes in the country.

Figure 3: Iranian poster for the film Dances with Wolves (translated in Iran as Bā gurg’hā mīraqsad), directed by Kevin Costner, 1990.

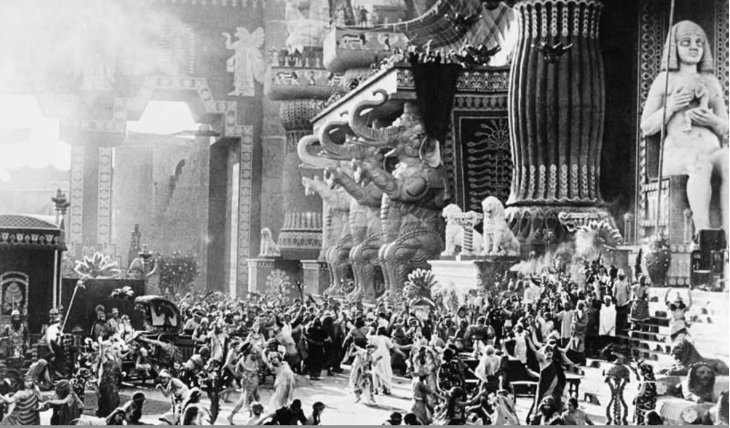

Figure 4: A scene from Intolerance, directed by D. W. Griffith (1916). In 1921, this film was screened in Iran under the title The Great Cyrus and the Babylonian Invasion.

The earliest major milestone

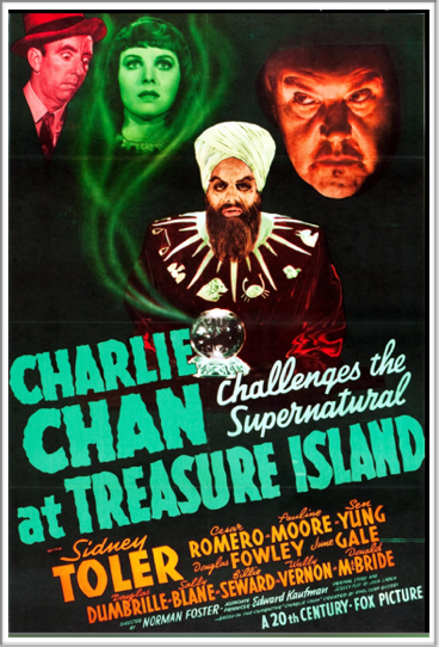

The first significant entry of the American film industry into Iran can be traced back to around 1945, shortly after the end of World War II.5Before World War II, Rizā Shah maintained strong diplomatic and economic ties with Germany, which had become one of Iran’s major trade and industrial partners. As a result, German cultural influence grew significantly in Iran during the 1930s, and one of the most visible aspects of this was the increased presence of German cinema. Films produced by the German company UFA (Universum Film AG), one of Europe’s most powerful film studios at the time, were screened in Iranian cinemas more frequently than films from most other foreign countries. “From a commercial point of view, the UFA group had operated beyond Germany’s national borders since its founding, pursuing a strategy of expanding its spheres of influence. The company’s activities abroad aimed, quite simply, to establish a media empire on a European scale […] to create a European center capable of counterbalancing Hollywood.” See Klaus Kreimeier, The UFA Story: A History of Germany’s Greatest Film Company 1918-1945, transl. Robert & Rita Kimber (University of California Press, 1996). Later, the Americans attempted to compete with German cinema: “their film imports to Iran increased by 60% in 1940, and by 70% to even 80% in 1943–1944.” See “Movies in the Middle East,” Foreign commerce weekly (May 29, 1943): 43. While American films had already trickled into the country—including Charlie Chaplin’s silent shorts, early Tarzan adventures, and other popular titles being screened in small, privately owned theaters in Tehran and other major cities—these were sporadic and mostly unofficial showings, with the films often imported by private distributors or cinema owners with foreign connections.

Figure 5: Poster for Charlie Chan at Treasure Island, directed by Norman Foster, 1939.

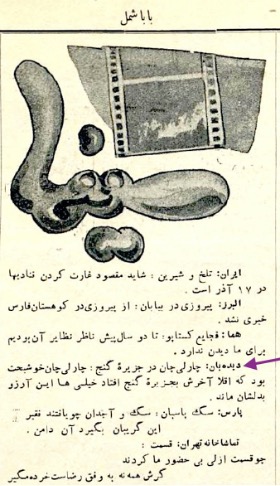

Figure 6: The film’s advertisement in the Iranian satirical magazine Bābā Shamal, 1943.

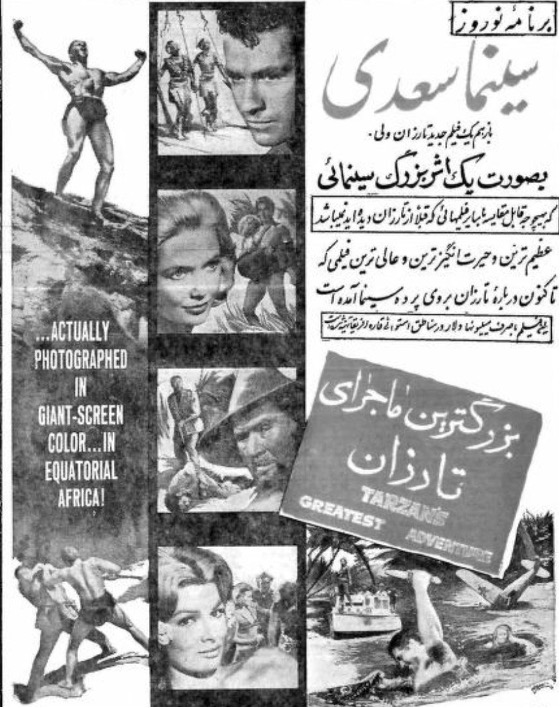

Figure 7: Iranian poster for Tarzan’s Greatest Adventure, directed by John Guillermin, 1959. The Tarzan series was one of the most successful American film franchises in Iran, enjoying widespread popularity from the early days of cinema in the country through the 1960s.

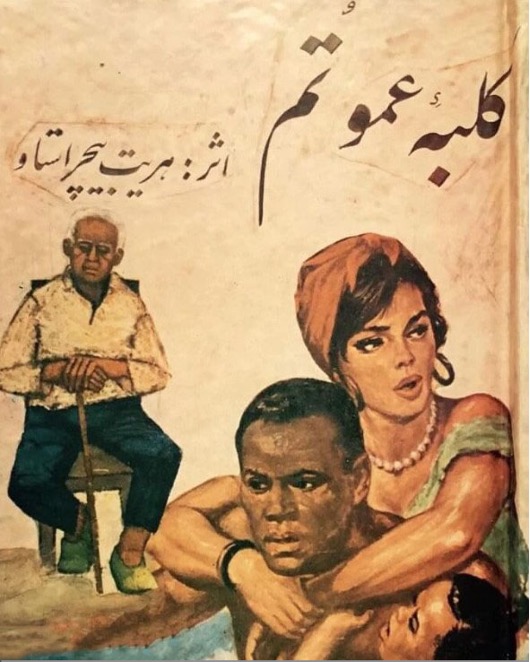

Figure 8: Book cover for the Persian translation of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852). The 1914 American film adaptation, directed by Robert Daly, was another widely popular American film in Iran during the 1920s.

Figure 9: Richard Talmadge was one of the most popular actors of the 1920s, with many of his films enthusiastically received by Iranian audiences. Photo from Film Magazine 17 (1984), 4.

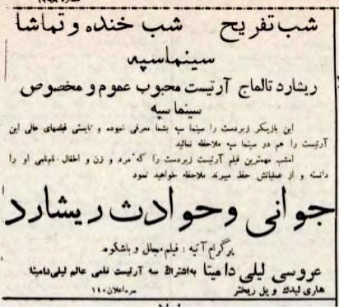

Figure 10: Advertisement in Ittilā‛āt newspaper (April 1931) for a film starring Richard Talmadge

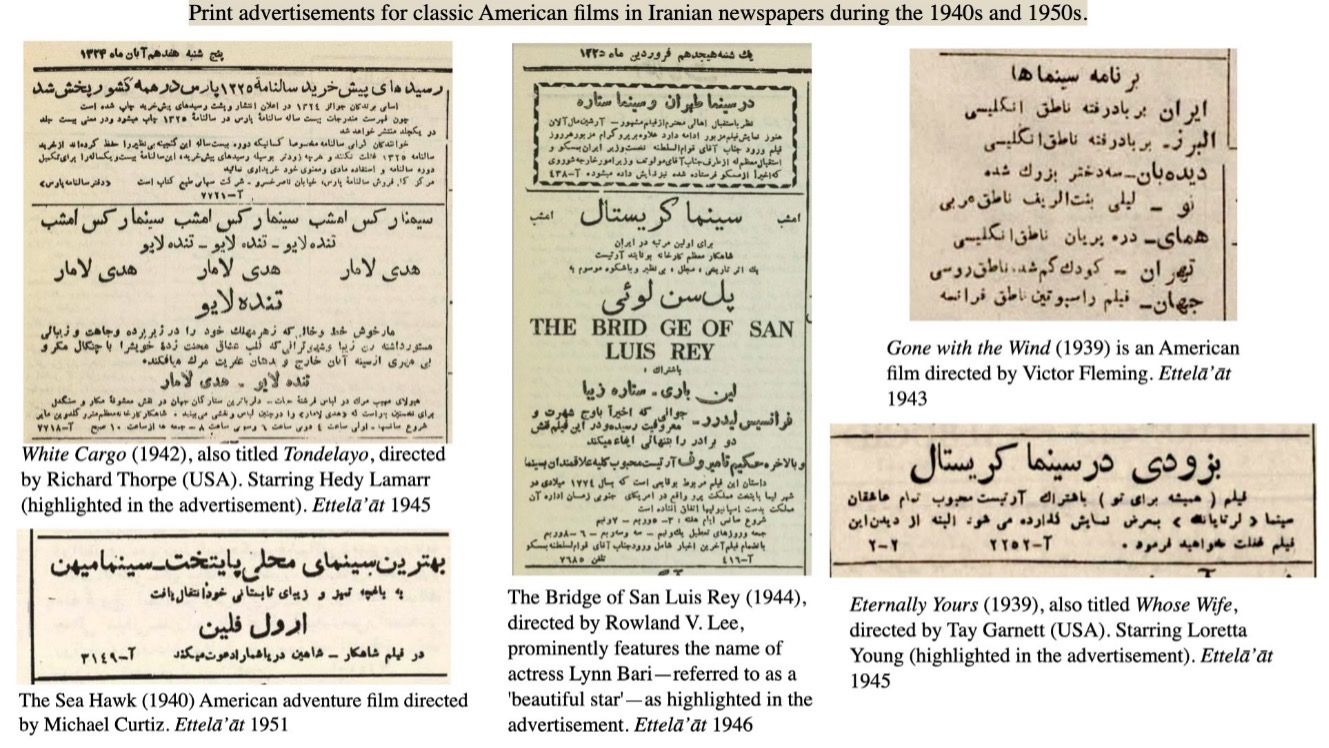

Figure 11: Print advertisements for classic American films in Iranian newspapers during the 1940s and 1950s.

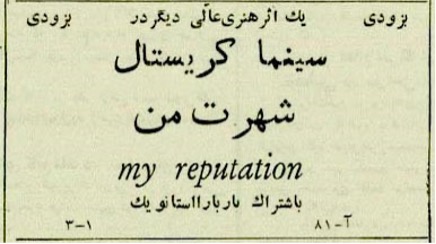

Figure 12: Advertisement for My Reputation (1946), an American film directed by Curtis Bernhardt, published in Ittilā‛āt newspaper (April 1950).

It was not until after 1945, however, that Iranian audiences saw a more organized and institutional introduction of American cinema. This coincided with growing U.S. global cultural influence and its strategy of soft power during the early years of the Cold War. Agencies such as the United States Information Agency (USIA),6It was the same U.S. Information Agency that established itself in Italy after World War II to implement the same training program as in Iran: contributing, among other things, to the production of Rome, Open City (Roma citta aperta) by Roberto Rossellini. “Citta aperta’s first screening took place August 28, 1945, under the auspices of the U.S. Information Agency at the Italian under ministry for press and spectacle.” See Tag Gallagher, The Adventures of Roberto Rossellini (Da Capo Press, 1998), 164. possibly with the support of institutions like the American Film Institute or related cultural organizations, facilitated the import and distribution of selected American films in Iran. These were shown not just for entertainment, but also as part of educational and cultural exchange programs. This period laid the groundwork for the eventual widespread popularity of Hollywood films in Iran, especially during the 1950s to 1970s, when American movies became a staple of urban entertainment, influencing not only audiences but also a new generation of Iranian filmmakers. The goals of this early cinematic presence were twofold:

- To promote American culture and values through Hollywood storytelling, thereby offering Iranian audiences a window into American life, ideals, and technologies.

- To introduce and popularize modern film as a medium of both education and entertainment. Screenings often included documentaries, educational reels, and films intended to teach ideas such as hygiene, modernization, democratic values, and technological progress.

The USIA organized training programs to teach Iranians how to produce news reports and documentary films. This system allowed the Americans, in a certain way, to create propaganda films in the form of newsreels or documentaries made by their Iranian trainees. For many Iranians living in remote villages and towns, these films were their very first encounter with cinema, as they were shown all over the country thanks to “mobile cinema”—a traveling cinema system using a van and a projector as a sort of itinerant film screening unit.7Mohammad Ali Issari, “A Historical and Analytical Study of the Advent and Development of Cinema and Motion Picture Production in Iran (1900-1965),” (PhD diss., University of Los Angeles, 1979), 232. These mobile cinemas extended reach, as the number of cinemas in 1945 did not exceed 35 across the entire country, with 13 located in Tehran. Only 5% of the population attended movie theaters.8“Movies in the Middle East,” Foreign Commerce Weekly (May 29, 1943): 43.

In order to launch their film operations, the Americans needed efficient and “native” intermediaries to help establish their branches in Iran. Thus, the first cinema operators in Iran emerged. These pioneering investors secured the earliest contracts with American film companies, while many of the domestic exhibitors were drawn from Iran’s Jewish and Armenian immigrant communities. It is quite plausible that the interactions with these companies were easier for Armenians and Jews than for Muslim Iranians. This is due, on one hand, to their dual cultural background and language, and on the other hand, because this type of business was still considered “haram” (forbidden or sinful) by many Muslim Iranians. Among the new cinema owners during this period, notable names include Zorkof, Kogan, ‛Alī Vakīlī, Arnold Yaʿqūbzādah, and several Russians who had been naturalized as Iranians. These Russians had arrived in Iran following the October Revolution in Russia, which brought about significant political and social changes in the region. Thanks to these new investors, the number of movie theaters soon increased to 80 by the end of 1950,9“Persia,” Reports on the Facilities of Mass Communication (Press, Film, Radio) (UNESCO, Paris, 1951). 142 by 1960, and 238 in 1962 (the year of the launch of the White Revolution by the Shah). In 1970, the total number of movie theaters in Iran was 440.10Hamīd Shu‛ā‛ī, Farhang-i Sīnimā-yi īrān [The Encyclopedia of Iranian Cinema] (Tehran, Herminco, 1975), 337.

American Cinema Took the Stage

By the 1950s and 60s, American films had established a strong and growing presence in Iran’s cinematic landscape. The influx of Hollywood productions coincided with Iran’s broader cultural opening and modernization efforts under the Pahlavī regime. Epic films such as One Million B.C. (1940), The Ten Commandments (1956), Ben-Hur (1959), Thunder in the Sun (1959), and other large-scale productions were particularly well-received by Iranian audiences.

Figure 13: Iranian poster for Thunder in the Sun, directed by Russell Rouse, 1959. The film was one of the most popular among Iranian cinema-goers when it was released in Iran in 1960.

Figure 14: Advertisement for One Million B.C., directed by Hal Roach, 1940. Although the film was produced in 1940, it was not screened in Iran until 1960, where it became a great success.

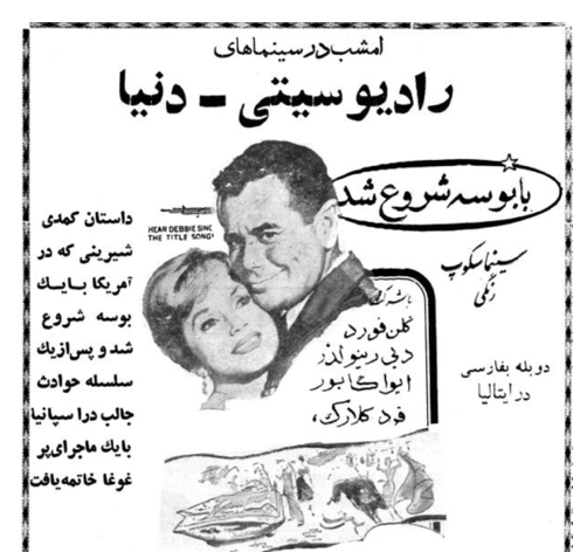

Figure 15: Iranian poster for It Started with a Kiss, directed by George Marshall, 1959. This American-style romantic comedy gained significant popularity and attracted many fans when it was screened in Iranian movie theaters in 1960.

These films, known for their lavish budgets, grand narratives, and groundbreaking special effects, offered a level of visual and technical sophistication that was unmatched by local productions at the time. Their appeal went beyond mere entertainment; they also introduced new cinematic techniques, storytelling formats, and aesthetic standards that deeply influenced the tastes of Iranian viewers. The sheer scale and spectacle of these movies—featuring historical and social themes, elaborate sets, and dramatic musical scores—resonated with a public eager for modern cultural experiences. According to Sitārah-yi Sīnimā magazine (no. 28), out of the 294 films screened in Iranian cinemas in 1954, 180 were American productions. In the same article, Cyrano de Bergerac (1950), directed by Michael Gordon, is noted as a major box office success and was ranked as the most successful film of the year in Iran in 1954.

American cinema became one of the dominant foreign influences on Iran’s film market during this period. U.S. films not only filled the programing of many newly built movie theaters but also played a key role in shaping the cinematic expectations of a generation of Iranians.11Among the most popular films were American action movies, particularly B movies. Notably, car chase scenes became a favorite spectacle, while the extended shooting sequences typical of Westerns increasingly drew audiences to theaters. Subsequently, Italian filmmakers capitalized on this trend by producing a prolific number of low-budget B action films and spaghetti Westerns. The primary markets for these productions were countries in the Middle East, with Iran representing a significant consumer base. Iranian audiences, supported by petrodollar wealth, attracted a growing number of Italian distributors, which facilitated the widespread distribution of this emerging genre. Among the most prominent examples were the film series starring Terence Hill and Bud Spencer, whose numerous action-comedy and spaghetti Western films achieved considerable popularity. Starting from the 1960s, actors in these films, such as Giuliano Gemma (The Bounty Killer by Duccio Tessari, 1968) and Franco Nero (Django by Sergio Corbucci, 1966), and especially his famous Keoma (by Enzo Castellari, 1976), became as popular and well-known as Iranian actors.

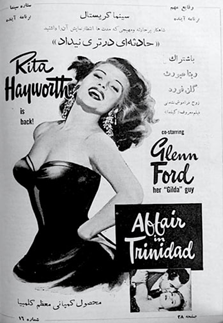

While American blockbusters became increasingly visible in Iran during the mid-20th century, the demographic and socioeconomic composition of their audience often diverged from that of the average Iranian moviegoer. Hollywood epics were predominantly screened in modern, upscale theaters (first class) situated in affluent neighborhoods of Tehran and other major cities such as Isfahan and Shiraz. These venues largely catered to the urban upper-middle class and elite, who were more receptive to foreign cultural imports and had greater access to leisure activities.

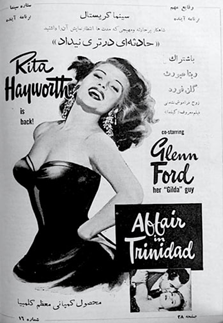

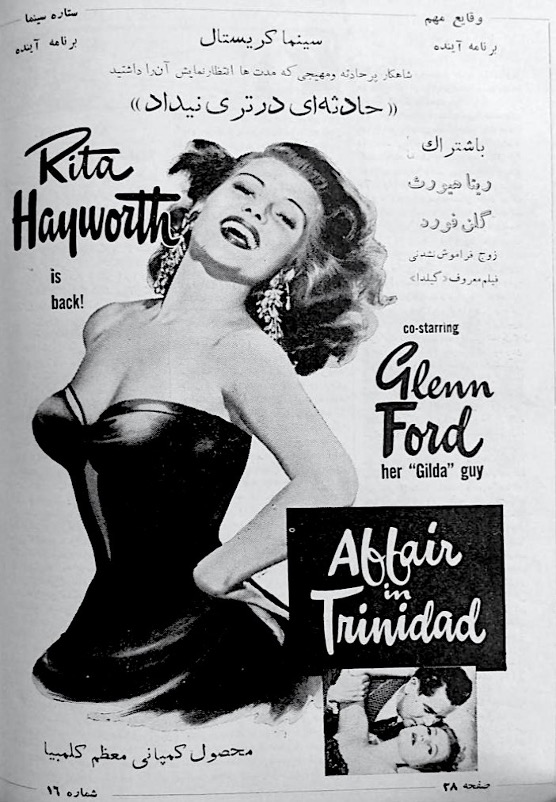

Figure 16: Cinema Cristal, one of the most prominent and active theaters in Tehran, gained a reputation for showcasing newly released American films that often featured bold or provocative themes. Displayed here is a 1960 publicity poster for Affair in Trinidad, directed by Vincent Sherman, 1952.

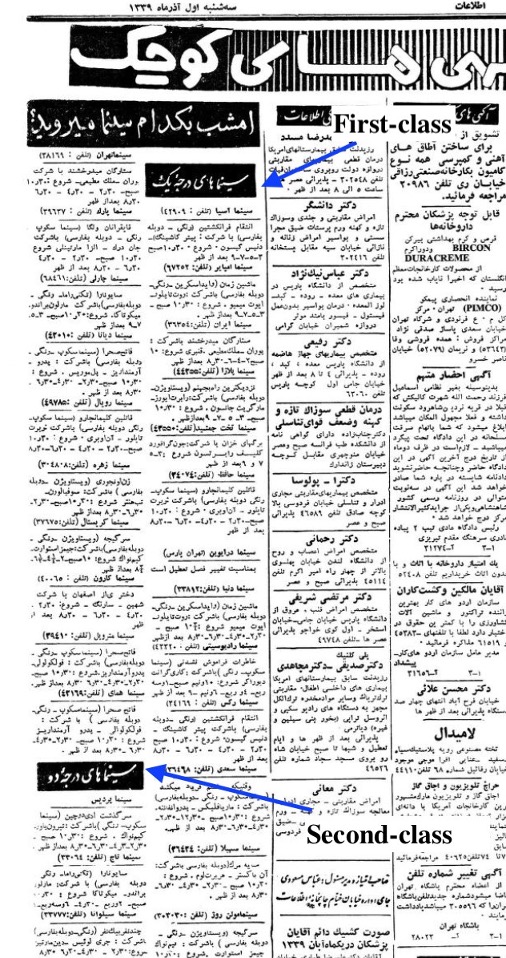

Figure 17: In many major cities, including Tehran, movie theaters were often divided into two categories: first-class and second-class. First-class cinemas, typically located in well-off neighborhoods, primarily screened films from the United States and other Western countries.

In contrast, the majority of cinemas located in the southern districts of Tehran and in economically marginalized areas tended to show local productions—often categorized under the popular genre known as Fīlm-fārsī. These films, though produced with far more modest budgets, reflected characters and narratives that were culturally familiar to their audiences.12This approach provided an opportunity for emerging filmmakers around the world to gain experience and transition into professional cinema. However, the practice was not always applied with discernment or grounded in artistic justification. As Jean Serroy explains: “Two primary motivations have consistently served to legitimize the remake of one film by another. In some cases, the goal is to adapt a film originally intended for one audience to suit another—often of a different nationality. Hollywood, for example, has long preferred to remake foreign films it deemed commercially promising rather than simply distribute the original versions in the American market […] In other equally common cases, the remake seeks to revive an older film—whether renowned or forgotten—in order to make it relevant for contemporary audiences. This may be done for purely commercial reasons or driven by more artistic ambitions.” See, Jean Serroy, Entre deux siècles: 20 ans de cinéma contemporain [Between Two Centuries: 20 Years of Contemporary Cinema] (Editions de La Martinière, 2006), 37. The process of remaking often extended beyond narrative and thematic elements to include culturally specific visual adjustments. For instance, in Western cinema, protagonists—particularly heroic or morally upright characters—are typically introduced entering the frame from left to right, a direction aligned with the natural reading flow in Western languages. In contrast, Iranian cinema frequently mirrors this convention by having the protagonist enter from the right side of the frame, consistent with Persian script and reading habits. This culturally informed spatial orientation reflects a deeper localization strategy, designed to create visual comfort and intuitive coherence for domestic audiences. The working-class spectators in these neighborhoods sought stories that mirrored their lived experiences: protagonists who resembled them physically, spoke in colloquial language, navigated similar social constraints, and inhabited comparable urban or rural environments. For such audiences, the polished, idealized worlds presented in American films—often led by blue-eyed protagonists navigating Western moral dilemmas—felt distant and unrelatable.

This dissonance in cultural representation prompted several Iranian filmmakers to begin adapting, and in some cases outright replicating, American cinematic narratives. These adaptations, often unlicensed, involved replacing foreign characters, locations, and values with their Iranian counterparts, effectively “Iranizing” the content.13This localization strategy became so prominent that, in some instances, voice actors dubbing American films into Persian would assign Iranian first names to foreign characters—such as Texans or New Yorkers—in an effort to create a stronger sense of familiarity for local audiences. For example, in a Western film, John Wayne might be renamed Gholām. Or in the dubbed version of Premier Rendez-vous (Her First Affair), directed by Henri Decoin (1941), the character opposite Danièle Darrieux was transformed into a young Iranian student named Īraj. “Altering the storyline, inserting humorous lines and so-called ‘slapstick’ dialogue to heighten the comedic tone, and having foreign characters speak in regional Iranian accents such as Turkish or Rashti gradually became common practices in film dubbing.” Ahmad Zhīrāfar, Tārīkh-i dūblah bi fārsī dar Īrān [Complete History Dubbing to Persian in Iran] (Edition Kulah-Pushtī, 2014), 611.

Such interventions went beyond linguistic translation; they constituted deliberate acts of cultural localization. Foreign characters were frequently assigned Iranian names, and their speech was infused with local idiomatic expressions or regionally resonant humor. Endings were sometimes rewritten to reinforce moral values or comply with state censorship. These modifications were not merely technical necessities, but strategic adaptations shaped by broader socio-political imperatives. As such, the practice of dubbing in Iran reveals the intricate dynamics between global cinematic forms and localized cultural production. In certain cases, dubbers went even further, modifying entire lines of dialogue, which in turn altered the narrative of the film itself. A significant portion of such interventions stem from censorship requirements. This is explicitly stated in a regulatory article mandating that all wrongdoers must be arrested and brought to justice by the end of the film. Article 6 of the Censorship Law, published by the Sāzmān-i Vazāyif-i Idārī-i Kull-i Nizārat va Namāyish va Āyīn’nāma-hā-yi marbūt bi Fīlm va Sīnimā [Central Office for the Supervision of Film and Cinema] (Tehran: MCA, 1976), 22.

For example, in the dubbed version of The Thomas Crown Affair (1968), the protagonist, Thomas Crown (played by Steve McQueen), expresses regret for his involvement in a heist and even promises to return the stolen money to the police.

It is interesting to note that the first director of Iran’s Film Censorship Office was Nilla Cram Cook (1908–1982), an American cultural attaché who established censorship guidelines in 1943 during the Allied occupation—well before the office became part of Iran’s Ministry of Culture. Her work primarily focused on the following: establishing Iran’s first film censorship board under Reza Shah’s exile government; instituting moral codes adapted from Hollywood’s Hays Code (1930); and banning “indecent imagery” as well as anti-Allied content. She was considered by Iranian filmmakers as ‘kāsah-yi dāghtar az āsh’—hotter than the dish itself—criticizing Cook’s regulations as being “more Puritan than Persian.” (Nasr, Cinema of Resistance, 2005). In doing so, directors preserved the structural and thematic elements of American scripts while localizing them for a domestic audience. The result was a wave of hybrid productions within the Fīlm-fārsī genre—films that drew inspiration from American cinema but were reimagined through a distinctly Iranian lens.14“The films of this commercial cinema, or ‘cinema farsi,’ remain extremely mediocre. Clumsily made and set in a timeless past, they rely heavily on exaggerated effects and turbulent plots, whose twists and character styles belong to the crudest kind of melodrama […] With minor differences, one can recognize the traditional structure of Egyptian cinema, which itself is a watered-down imitation of Hollywood cinema.” Guy Hennebelle, Les Cinémas Nationaux Contre Hollywood [National Cinemas Against Hollywood] (Guy Gauthier, Éditions du Cerf, 2004), 238. This practice of cultural appropriation extended beyond American cinema, encompassing popular Indian, Italian, and even French films, many of which were similarly localized to suit the tastes of Iranian viewers.15Amīr Shirvān, one of the well-known filmmakers of the time, explained the reasons behind the success of his films in an interview: “The reasons are multiple—first, the story itself; then the fact that the story unfolds in settings familiar to the audience, which they find entertaining. But above all, spectators appreciate the actors, with whom they feel a close connection and genuine affection.” See, Sitārah-yi Sīnimā 788 (1972), 34.

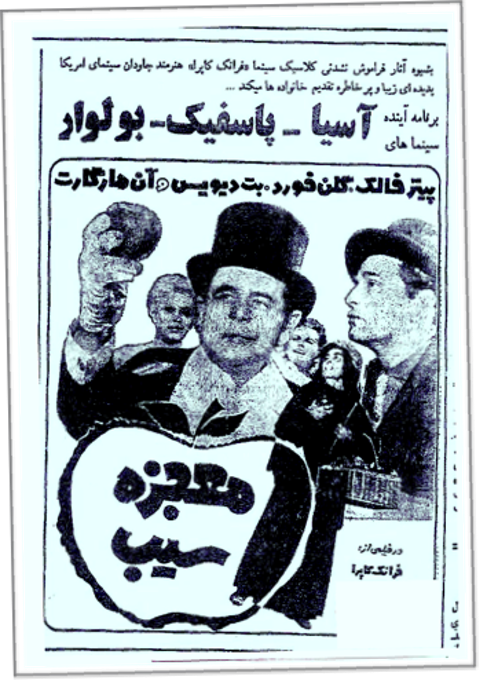

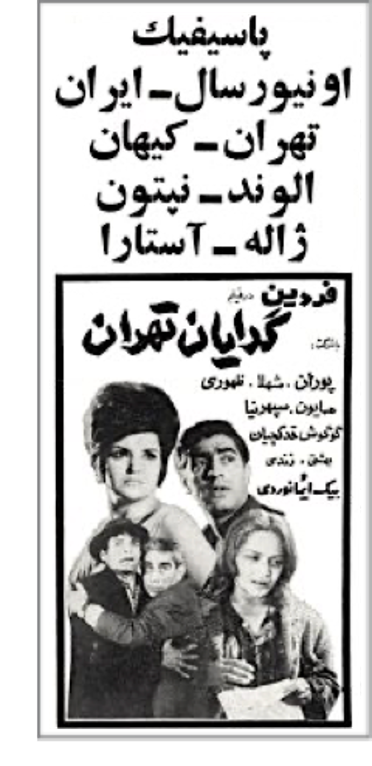

It should also be noted that the impact of foreign cinema on Iranian filmmaking manifested in two distinct ways. On the one hand, successful newly released international films were promptly remade with Iranian actors and settings to recapture audience interest. On the other hand, older but popular films from Europe or North America were adapted into new Iranian versions. One such example is the film Gidāyān-i Tihrān (The Beggars of Tehran, 1966), a remake of Frank Capra’s Pocketful of Miracles (1961).

Figure 18: Advertisement for Frank Capra’s Pocketful of Miracles (1961) in an Iranian newspaper, 1964.

Figure 19: Promotional image for Gidāyān-i Tihrān (The Beggars of Tehran, 1966), an Iranian cinematic remake of Pocketful of Miracles, directed by and starring Muhammad ‛Alī Fardīn.

![Figure 20 (left): Poster for The Defiant Ones, directed by Stanley Kramer, 1958. It starred Tony Curtis and Sidney Poitier as two escaped prisoners. “[…] Mr. Shaybānī, the producer, liked the film [The Defiant Ones] and asked me [Rizā ‛Aqīlī] to write a similar screenplay. So I wrote Nājūr’hā (The Crooks, 1974), directed by Sa‛īd Mutallibī, in which they intended to cast Bayk Īmānvirdī and Fardīn in the roles corresponding to Curtis and Poitier.”<sup class="modern-footnotes-footnote " data-mfn="1" data-mfn-post-scope="0000000019083a7300000000535f084f_18572"><a href="javascript:void(0)" role="button" aria-pressed="false" aria-describedby="mfn-content-0000000019083a7300000000535f084f_18572-1">1</a></sup><span id="mfn-content-0000000019083a7300000000535f084f_18572-1" role="tooltip" class="modern-footnotes-footnote__note" tabindex="0" data-mfn="1">Rizā ‛Aqīlī (screenwriter), interview with Ittilā‛āt (March 1976). </span> Figure 20 (right): Poster for Nājūr’hā (The Crooks), directed by Sa‛īd Mutallibī, 1974.](https://cinema.iranicaonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Picture1-11.png)

Figure 20 (left): Poster for The Defiant Ones, directed by Stanley Kramer, 1958. It starred Tony Curtis and Sidney Poitier as two escaped prisoners. “[…] Mr. Shaybānī, the producer, liked the film [The Defiant Ones] and asked me [Rizā ‛Aqīlī] to write a similar screenplay. So I wrote Nājūr’hā (The Crooks, 1974), directed by Sa‛īd Mutallibī, in which they intended to cast Bayk Īmānvirdī and Fardīn in the roles corresponding to Curtis and Poitier.”[mfn]Rizā ‛Aqīlī (screenwriter), interview with Ittilā‛āt (March 1976). [/mfn] Figure 20 (right): Poster for Nājūr’hā (The Crooks), directed by Sa‛īd Mutallibī, 1974.

Figure 21: A still from Kākū (Kako), directed by Shāpūr Gharīb, 1971. “The script of Kako (1971) directed by Shāpūr Gharīb, borrows from classic American Western movie tropes: A once-noble man returns to a town he abandoned years ago. In his prime, he was a formidable force for justice—protecting the weak and upholding order. But in his absence, a ruthless usurper seized power, oppressing the very people the hero once swore to defend. Now, his return ignites a spark of hope, rallying the townsfolk against their oppressor.”[mfn]Hasan Tihrānī, “Persian Title of the article,” Tamāshā magazine 11 (1971): 56

Figure 22: Mahvash, a famous Iranian singer. “In some unusual practices, certain distributors went as far as inserting Iranian songs and dance sequences into the middle of American movies. In one film starring Gary Cooper, when he enters a saloon, we suddenly see Mahvash — a famous Iranian singer at the time — appear on screen, singing and dancing as if she were part of the original cast, as though she had actually acted in the American film alongside Gary Cooper.”[mfn]Author, “Persian Title of the article,” Ittilā‛āt (April 1976): 34

Late 1960s and Early 1970s

By the late 1960s and into the early 1970s, American cinema underwent a profound transformation, reflecting the turbulent political and cultural shifts of the time. Filmmakers in the United States began to produce socially conscious works that engaged with issues such as systemic corruption, racial injustice, the Vietnam War, and class inequality.16“Whereas from the 1940s to the 1950s, from Truman to Eisenhower, continuity prevailed, the election of John F. Kennedy in 1961 instead marked a break—at least an apparent one. A break, because for the first time, a Catholic reached the nation’s highest office. A break, because there was a return to the spirit of the pioneers, with talk of opening a ‘New Frontier,’ and fighting for social progress and racial equality: African Americans, and more generally the underprivileged, naturally voted overwhelmingly for the Democratic candidate.” Jean-Loup Bourget, Le cinéma américain 1895–1980 (Presses Universitaires de France, 1983), 171. As Michael Ryan and Douglas Kelner note:

In the late 1960s many Hollywood films, responding to social movements mobilized around the issues of civil rights, poverty, feminism, and militarism that were cresting at the time, articulated critiques of American values and institutions.17Michael Ryan and Douglas Kelner, “Films of the Late 1960s and Early 1970s,” in Hollywood’s America: Understanding History Through Film, ed. Steven Mintz, Randy Roberts and David Welky (Wiley Blackwell Editions, 2016), 270.

Films such as The Graduate (1967) by Mike Nichols, Point Blank (1967) by John Boorman,18Among these films, Point Blank particularly captured the attention of a young Iranian filmmaker, Masʿūd Kīmiyāʾī. The film centers on the revenge of a lone gangster who has been betrayed by his accomplices, losing both his money and his wife. The theme of “revenge” in Point Blank would later reappear in Masʿūd Kīmiyāʾī’s future film Qaysar (Gheisar), marking a significant influence on his early cinematic style.

“Revenge is a traditional Iranian them and greatly utilized by Iranian filmmakers […] Revenge is carried out mainly by the male members of a family or tribe.” See, Peter Chelkowski, “Popular Entertainment, Media, and Social Change in Twentieth-Century Iran,” in The Cambridge History of Iran, vol. 7, ed. Peter Avery, Gavin Hambly, and Charles Melville (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 796. Bonnie and Clyde (1967) by Arthur Penn, Cool Hand Luke (1967) by Stuart Rosenberg, Bullitt (1968) by Peter Yates, and The Thomas Crown Affair (1968) by Norman Jewison prominently featured male characters as their primary protagonists.19

“On every Hollywood front, and for nearly every major screen talent, the 1960s proved to be far more agreeable to male actors. […] Most subtly, the standard characterization of ‘masculinity’ in American movies shifted. Rugged, individualistic, and aggressive male types still found work as Hollywood leads, but a set of more tentative and reflective character types emerged during the 1960s to share the American screen with them. Among the male Hollywood leads of the decade whose screen personas best reflected these shifts—albeit in varying ways and to different degrees—were Paul Newman, Robert Redford, Warren Beatty, and Steve McQueen.” Paul Monaco, The Sixties 1960-1969, History of the American Cinema (University of Californian Press, 2003), 139.

This shift, of course, did not escape the attention of Iranian filmmakers such as Masʿūd Kīmiyāʾī, who assigned leading roles to male actors—roles that were often performed with a clear inclination toward the style of American actors of the period. These characters reflected a shift in cinematic representation, as the traditional American hero gave way to figures marked by psychological depth, moral ambiguity, and an increasing alienation from societal norms. As Géraldine Michelon observes, “The late 1960s marked the end of a certain vision of America. It was the ‘end of innocence’ and the rise of a counterculture embraced by the younger generations.”20Géraldine Michelon, Larousse du Cinéma, ed. Laurent Delmas and Jean-Claude Lamy (Paris: Larousse, 2005), 164.

These American films, which often challenged the status quo, resonated with a generation of Iranian filmmakers who were increasingly disillusioned with formulaic Fīlm-fārsī conventions.21As stated in Assadi-Nik’s thesis, the percentage of American films shown in theaters in Tehran in the 1970s was quite high, ranking immediately after Iranian films and before all other foreign films: “Iranian 51.6%, USA 30.8%, Italian 9.9%, Indian 4.4%, French 3.3%.” see, Ali-Naghi Assadi-Nik, “Les moyens de communication de masse (presse, radio, cinéma et télévision) en Iran,” (PhD thesis, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Paris, March 1973), 213. Directors such as Masʿūd Kīmiyāʾī emerged at the forefront of what came to be known as the Iranian New Wave—a movement characterized by realism, psychological depth, and socio-political critique.22Kīmiyāʾī made his first independent works by creating advertisements for American films. These commercials were made for films such as The Hustler (1961) by Robert Rossen, The Killers (1964) by Don Siegel, and The Cincinnati Kid (1965) by Norman Jewison. Kīmiyāʾī learned the craft of filmmaking under Khāchīkiyān, an Iranian filmmaker of Armenian origin, who was also known for his action films. Khāchīkiyān was highly regarded for his taste for American cinema. This influence of American cinema never left Kīmiyāʾī and continued to follow him throughout his filmmaking career, spanning the 1970s and 1980s. A large part of his scripts and characters were greatly influenced by those in American films (for example, Surb, made in 1988, was largely inspired by Once Upon a Time in America by Sergio Leone, 1984).

In parallel with the emergence of these new sensibilities in Iranian cinema, the Iranian market saw a dramatic increase in the screening of American films. This influx coincided with the height of Hollywood’s global dominance. Works by directors such as Sam Peckinpah, Don Siegel, and Francis Ford Coppola became particularly popular. Bonnie and Clyde (1967), The Godfather (1972), Dirty Harry (1971), M*A*S*H* (1970), No Orchids for Miss Blandish (1971), and Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974) were among the most well-received titles in Iran during this period. Some of the other remarkable films that had a profound impact include John Boorman’s Deliverance (1971), Milos Forman’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), John G. Avildsen’s Rocky (1976), Brian De Palma’s Obsession (1976), John Schlesinger’s Marathon Man (1976), and Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976).23

“We are witnessing a resurgence of gangster films, emblematic of the 1930s: heralded by Don Siegel’s Baby Face Nelson (1957) and Roger Corman’s Machine-Gun Kelly (1958), continued with Budd Boetticher’s The Rise and Fall of Legs Diamond (1960); Roger Corman’s The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre (1967), which reconstructs the ‘historical’ events of Chicago on February 14, 1929, more literally than Party Girl (N. Ray, 1958); and Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde (1967). One can also cite Frank Capra, who portrays celluloid gangsters in his fairy tale Pocketful of Miracles (1961), a remake of Lady for a Day (1933), based on Damon Runyon. Around the same time, the southern penitentiaries, a setting from I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1932), reappear in Cool Hand Luke (1967) by Stuart Rosenberg.”

Jean-Loup Bourget, Le Cinéma Américain 1895-1980 (Presses Universitaires de Science, 1983), 176. Marked by their raw energy, intense characterizations, and occasionally subversive narratives, these films offered both aesthetic inspiration and thematic frameworks for a new generation of Iranian directors, including Amīr Nādirī and Jalāl Muqaddam.24

Later, some Iranian filmmakers began creating equivalents of American actors in Iranian cinema — for example, Bayk Īmānvirdī as the counterpart to Charles Bronson, or depending on the script, as Peter Falk; and Jamshīd Āryā as a stand-in for Yul Brynner or Sean Connery. Other actors emulated the acting methods of American stars — such as Bihrūz Vusūqī, who drew inspiration from Marlon Brando and James Dean. This actor, a favorite of director Masʿūd Kīmiyāʾī, has long acknowledged Brando’s influence on his performance style. He stated:

“I was really influenced by James Dean and Marlon Brando. I always tried to be on Brando’s level. And Dean — well, we were from the same generation. He was about my age. We were living through the same things — him in America, me in Iran. We were far apart, sure, and from different worlds, but somehow, we had the same worries and the same kind of sorrow.” Bihrūz Vusūqī in an interview with the author in 1996 at the University of Toronto, Canada.

These American influences significantly contributed to the evolution of acting techniques among Iranian actors, who had previously relied primarily on theatrical performance styles that often failed to resonate authentically with Iranian character portrayals.

The aesthetic and ideological impact of these American films extended far beyond surface-level imitation. As Jean-Baptiste Thoret insightfully notes, “Post-1968 American cinema, subjugated to a logic of implosion, with circularity as the master form of an energy that threatens to suffocate. [Films] serve as an energy reservoir, but they also convey a state of history doomed to stutter.”25Jean-Baptiste Thoret, Le Cinéma Américain des années 70 (Edition Cahier du Cinéma, 2006), 77.

The symbolic resonance of American cinema—especially its portrayal of disillusionment, resistance, and existential crisis—helped shape the narrative and visual grammar of Iranian New Wave filmmakers. As Pauline Kael notes in her essay “Trash, Art, and the Movies,” “The heroes of the best early-60s films were insane […] but by 1967, the madness had turned outward—Bonnie and Clyde’s violence was a spit in the face of Depression-era morality. The new heroes weren’t sick; they were society’s executioners.”26Pauline Kael, “Trash, Art, and the Movies,” Harper’s Magazine (February 1969): 66. Thus, American cinema in this period not only influenced Iranian viewing habits but also profoundly reshaped Iranian cinematic production, ushering in a new wave of artistic experimentation and socio-political commentary.

Gavazn’hā (The Deer-1974) directed by Masʿūd Kīmiyāʾī: An example among others

Despite the heavy-handed censorship enforced by authorities in the 1970s, Iranian filmmakers, much like their American counterparts at the time, began to push the boundaries of expression. “I think it was for the film Gavazn’hā, because of the kick that police gave him [during the interrogation about this film], which caused internal bleeding in his intestines.”27Rizā Shukrallāh, Hamīd Tūrānpūr, Qaysar: Nimād-i Insān Mu‛tariz [Qaysar: The Manifesto of a Man] (Qasīdah Edition), 158.

Films like Gavazn’hā (The Deer-1974),28Gavazn’hā (The Deer), often considered one of the most important films in the Iranian New Wave movement. The film tells the story of Qudrat, a leftist revolutionary who has spent years in prison. The narrative unfolds as Qudrat tries to reconnect with the world and people he left behind, including his best friend Sayyid. directed by Masʿūd Kīmiyāʾī, managed to address themes of alienation, poverty, and existential despair, drawing both from Iranian realities and international cinematic influences while still operating under surveillance.

In the final version, however, Kīmiyāʾī was forced by the censor to change the ending of his film. The film ends with Qudrat’s hand dropping the gun before he dies. The scene is followed by an image of a lush green garden. Another requirement was that the censors made Kīmiyāʾī reshoot a scene in which Sayyid kneels before a policeman asking for forgiveness.

Moreover, Kīmiyāʾī only introduces the police at the very end of Gavazn’hā. This is a faithful representation of the censorship office’s regulations,29“Article 6: All characters who have committed a wrongdoing must not be left unpunished,” In Sāzmān-i Vazāyif-i Idārī-i Kull-i Nizārat va Namāyish va Āyīn’nāmah-hā-yi marbūt bi Fīlm va Sīnimā [Central Office for the Supervision of Film and Cinema] (Tehran: MCA, 1976), 22. but it has the opposite effect. It is clear that Kīmiyāʾī developed this critical perspective and confidence thanks to American films such as Bonnie and Clyde, Cool Hand Luke, and The Dirty Dozen. His characters are new heroes capable of standing up to the police. “Police are unsympathetic in most of these movies (in 1960s) […] in the end of Bonnie and Clyde the police sneakily, viciously murders the buoyant young criminals: the slow motion death sequence, which everyone has praised, painfully intensifies our feelings or revulsion and hatred for the executioners […] Cool Hand Luke is notable for its total, unrelieved hostility toward the prison warden and guards.”30Stephen Farber, “The Outlaws,” Sight and Sound 5 (autumn 1968): 171-72.

Masʿūd Kīmiyāʾī’s American Inspirations

- a) Serpico (1973) by Sidney Lumet

Sidney Lumet’s Serpico,31

Lumet’s Serpico tells the story of an honest police officer, Frank Serpico (played by Al Pacino), who rebels against the corruption within the New York Police Department and the broader justice system. He believes that the city’s inability to rid itself of crime and corruption stems from the failure of the police to set a moral example. The film takes place largely within the police station, offering an introspective examination of the institution:

“Once again, one could highlight the daring nature of American liberalism in its willingness to publicly criticize even its most sacred institutions—here, the New York Police.” Freddy Buache, Le cinéma américain 1971-1983 (Edition L’âge D’homme, Lausanne, 1985), 38. screened in Tehran in 1973, is one of the American32In co-production with Italy. films particularly admired by Masʿūd Kīmiyāʾī. Lumet’s work—especially this film—inspired the young Iranian filmmaker to make films that critique Iran’s social and institutional systems. Although these critiques are less direct than Lumet’s, they mark a significant first step in Iranian cinematic history. Kīmiyāʾī’s critical stance was unprecedented in the country’s film landscape.

After premiering at the Tehran International Film Festival in November 1974, the film encountered such severe censorship that its Tehran theatrical release was delayed until January 1976, mere months before the revolution began. At that time, the Censorship Bureau and the police administration were highly sensitive to political critique, making such a film seem nearly impossible: “Kīmiyāʾī received only negative responses from producers. They said: this script will likely be censored because it contains too many political elements.”33Hasan Sharīfī, Pīshkisvatān-i sīnimā-yi Īrān [The Founders of Iranian Cinema] (Khalīliyān Publishing, Tehran, 2006), 171. But Kīmiyāʾī, true to himself, took the risk of tackling dangerous subjects, and the boldness of American filmmakers—Lumet in particular—encouraged him in this direction.

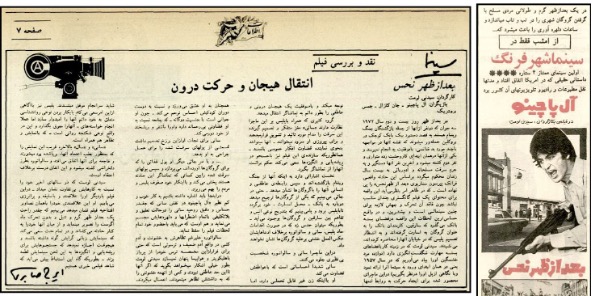

Figure 23: Advertisement for Serpico accompanied by a critical review, published in the Iranian daily Ittilā‛āt 14626 (1973).

Lumet’s protagonists, like Serpico, are outraged by social injustice and are driven by a thirst for justice. They must act on their own initiative without waiting for help from authorities. In Serpico, nearly every character—even within the police—is corrupt, leaving the protagonist to confront the system alone. This solitary hero bears no resemblance to traditional superheroes such as Superman or his British counterpart, James Bond. Instead, he is an ordinary, honest, and upright man—qualities that made him both compelling and relatable to 1970s audiences.

Much like Serpico, Gavazn’hā’s Qudrat is an ordinary man driven by life’s circumstances to stand against injustice. Qudrat is similarly a citizen of a modern society plagued by corruption and inequality. Neither character resigns himself to the situation. Serpico must “clean up” the police department alone, and similarly, Qudrat and his friend Sayyid choose to seek revenge on their own—without the help of family, neighbors, or especially the police.

This critical view of law enforcement is taken even further in Gavazn’hā. When the revolutionary leftist Qudrat and his drug-addicted childhood friend Sayyid are surrounded by police, their deaths are depicted violently through a grenade explosion initiated by the authorities. These officers symbolize the corrupt ruling power, opposed by both the intellectual youth (Qudrat) and the marginalized, forgotten youth (Sayyid), both are victims of poverty and drugs.

In a poignant scene at the end of the film, Sayyid tells Qudrat, “Together again, like when we were kids.” They both die moments later, symbolizing a shared sense of rebellion that cuts across all layers of Iranian society. The country’s social tensions needed only a spark to ignite—soon realized with the outbreak of the revolution in 1977.34In the final version, Kīmiyāʾī is compelled by censorship to alter the film’s ending. In fact, the film concludes with Qudrat dropping the gun before his death. The scene is then followed by an image of a lush green garden. Another requirement: censorship forces Kīmiyāʾī to reshoot a scene in which Sayyid kneels before a police officer, asking for forgiveness.

- b) Dog Day Afternoon (1975) by Sidney Lumet

Gavazn’hā is also heavily influenced by another of Lumet’s films: Dog Day Afternoon (1975). In Dog Day Afternoon, three amateur bank robbers impulsively attempt a heist. One flees immediately, while the remaining two (like Gavazn’hā’s protagonists) find themselves surrounded by police and are violently killed at the end. This deliberately anti-climactic conclusion mirrors Gavazn’hā’s own rejection of conventional narrative resolution.

Lumet uses these characters to explore American society’s relationship with its outcasts. Kīmiyāʾī does the same with Qudrat and Sayyid. Both directors present a microcosm of a closed society, where the characters are trapped inside brick buildings surrounded by armed police—already doomed to death.

Despite their flaws and cowardice, these antiheroes are embraced by the public in the films. In Gavazn’hā, neighborhood residents gather outside Sayyid’s home, reminiscent of spectators at a traditional Zurkhānah wrestling match. In Dog Day Afternoon, Sonny and his partner wave to the crowd outside the bank like celebrities, receiving applause: “The misunderstanding, the rigid violence, and the empty promises of the authorities ultimately humanize Sonny, who, waving a handkerchief like a white flag, regularly steps outside to negotiate with police commanders—always cheered by the onlookers.”35Freddy Buache, Le cinéma américain 1971-1983 (Edition L’âge D’homme, Lausanne, 1985), 40.

In both Gavazn’hā and Dog Day Afternoon, characters like Sayyid and Sonny slowly realize they are mere pawns in a corrupt system. This realization leads Sayyid to take matters into his own hands by killing the local drug dealer responsible for his suffering, choosing to fight back even at the cost of his own life. Similarly, Sonny’s actions in Dog Day Afternoon reflect his own rebellion against a system that has marginalized him. “Sonny discovers he has been cynically manipulated by society […] Through his contradictory actions, Sonny reveals the crushing terror of a diseased society and the despair it breeds in individuals.”36Freddy Buache, Le cinéma américain 1971-1983 (Edition L’âge D’homme, Lausanne, 1985), 40.

What makes these characters so moving—both in Lumet’s and Kīmiyāʾī’s work—is their blend of naïveté and realism. They live partly in a dream world, yet are forced to confront harsh realities. “The modern fact is that we no longer believe in the world. Not even in events like love or death, which seem only half real. It’s not us making cinema—it’s the world that appears like a bad movie.”37Gilles Deleuze, L’image-mouvement (Paris, Coll. “Critique,” editions de Minuit, 1983), 223.

The simplicity of these stories is grounded in everyday life, with characters’ actions portrayed as instinctive responses—almost animalistic—to their environment. Characters such as Sayyid and Qudrat, much like Sonny and Sal, are paradoxical: tough yet fragile, cowardly yet brave, dependent yet independent—in short, they are simply human. Their contradictions make them deeply relatable “We all intellectualize about why we should do things, but it’s our purely animal instincts that are driving us to do them all the time.”38Prince Stephan, Savage Cinema: Sam Peckinpah and the rise of ultraviolent movies (University of Texas Press, 1998), 104. These irreducible contradictions render them profoundly relatable as complex psychological subjects. “Images no longer reflect a unified or synthetic reality but a fragmented one. Characters shift from central to peripheral roles and back again.”39Gilles Deleuze, L’image-mouvement (Paris, Coll. “Critique”, editions de Minuit, 1983), 279.

Figure 24: A promotional advertisement for the film Dog Day Afternoon (1975), accompanied by a critical review published in the Iranian daily Ittilā‛āt in 1977.

The contradictions (or missteps) of the protagonists compel the other characters in the film to side with and assist them. In Dog Day Afternoon, Sonny’s hostages grow sympathetic toward him and even end up aiding his cause—as does the crowd outside the bank. Similarly, in Gavazn’hā, Fātī (Sayyid’s wife) and his neighbors rally to help him and Qudrat.

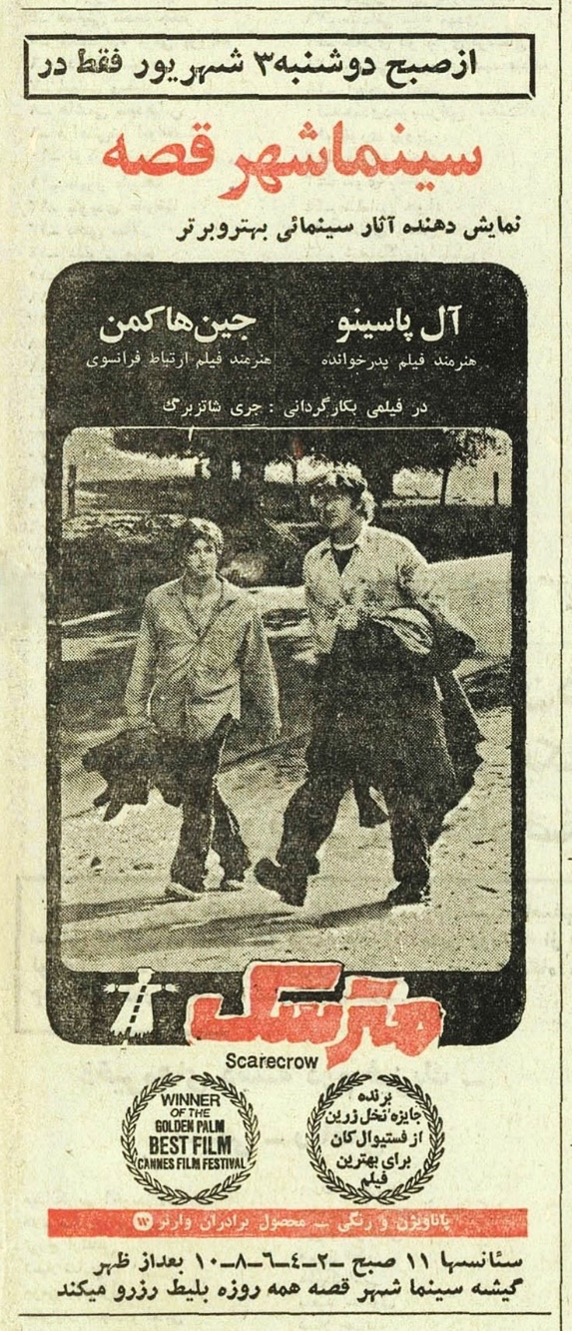

- c) Scarecrow (1973) by Jerry Schatzberg

A similar thematic approach is evident in Jerry Schatzberg’s Scarecrow (1973), which tells the story of two lost friends confronting an unforgiving world.40Scarecrow ranked among Tehran’s top 10 box office hits for 1974. See, Sitārah-yi Sīnimā (March 1974): Page number. Given the film’s considerable success in Iran, it likely exerted influence on Kīmiyāʾī’s work, as both filmmakers exhibit similarly pessimistic and melancholic social critiques in their cinematic visions.41In a interview, Masʿūd Kīmiyāʾī said: : “My new film is called Gavazn’hā. It’s a movie about two high school friends who reunite after 10 years—only out of necessity. When they meet, they realize everything has changed: life has turned bitter, worse, and full of burdens- exactly the harsh truths I want to explore in this film.” Author, “Harf’hā-ye bā Mas’ūd Kimiāei” (Conversations with Masʿūd Kīmiyāʾī ), Cinema 53 (March 1974)): 19.

Figure 25: Advertisement for Scarecrow (1973) in Ittilā‛āt newspaper, 1976.

This American road movie—traversing the route from Denver to Pittsburgh—follows two marginalized figures: Max, recently released from prison (evoking parallels with the revolutionary figure of Qudrat), and Lionel, a former sailor. They meet while hitchhiking, their economic precarity emphasizing their outsider status. Traveling by truck, passing through provincial towns, and hopping freight trains, they gradually share their histories, aspirations, and disillusionments.

Lionel dreams of reuniting with the son he has never met, only to discover that the child was never born—a cruel fabrication. Max harbors the modest ambition of opening a car wash with his savings. As in Gavazn’hā, a dynamic of protection and brotherhood emerges: Max defends Lionel after he is attacked, urging him not to surrender to despair. Likewise, Qudrat urges Sayyid to stand up to the drug dealer and safeguard his family. Lionel—slight and emotionally vulnerable—perceives Max as a guardian figure: a gentle giant whose glasses (a recurring cinematic emblem of thoughtfulness or intellectualism) signal inner sensitivity. Notably, Qudrat too wears glasses, reinforcing the visual and thematic resonance between the characters.

The journey through a bleak, alienating America offers a sobering contrast to the triumphant arc of pre-war cinematic heroes who rose from poverty to prosperity. In contrast to these earlier characters, Max and Lionel embody a clear-eyed pessimism—one rooted in disenchantment rather than defeatism. Schatzberg’s drifters traverse a post-industrial wasteland where the American Dream is a lie, symbolized most obviously in Lione’s non-existent son. “While many American veterans are treated with shame, this film presents the failed reintegration of two pariahs […] Lionel’s wife delivers the final blow by telling him their child is dead.”42William Bourton, Le Western, une histoire parallèle des Etats-Unis (Presse Universitaires de France, Paris, 2008), 269.

The ending of Scarecrow is as dark as that of The Deer (Gavazn’hā) or Dog Day Afternoon: both of the main characters are helpless and lost, and even friendship can no longer offer solace. This deep bond between two lost souls dies, giving way to a society that is policed, violent, merciless, and arbitrary. Lionel’s catatonic state becomes a cry of despair in a collapsing America. Even though, unlike the protagonists of The Deer (Gavazn’hā) or Dog Day Afternoon, Lionel and Max do not die at the end of the film, their despair leads them to a kind of psychological death (Lionel is sent to a psychiatric hospital)—a fate that seems far more difficult to endure than physical death. Ultimately, all those on the margins—the disoriented and the dispossessed—become society’s test subjects. Their disastrous fates serve only to frighten the middle class into obedience, warning them that any defiance of the system will result in a similar punishment.

Gavazn’hā was granted release in part because of its tragic ending, which conformed to one of the most important rules imposed by the censorship office at the time: “No wrongdoer shall escape punishment.”43“Article 6: All characters who have committed a wrongdoing must not be left unpunished,” In Sāzmān-i Vazāyif-i Idārī-i Kull-i Nizārat va Namāyish va Āyīn’nāmah-hā-yi marbūt bi Fīlm va Sīnimā [Central Office for the Supervision of Film and Cinema] (Tehran: MCA, 1976), 22. From the censors’ perspective, the film successfully fulfilled its ideological purpose by concluding with the protagonists’ (Qudrat and Sayyid) deaths—a narrative resolution that aligned with state-approved moral frameworks. From the perspective of the censors, the film served its disciplinary function: the two “scarecrows” (as the protagonists of Gavazn’hā were perceived) offered a stark warning to the public (i.e., the spectators) against transgression, lest they suffer the same consequences.44Some believe the film was allowed to be screened thanks to the strong influence of its producer, who had close ties to the regime. As Sharīfī explains: “The film directly challenged the system […] the festival brochure in Tehran repeatedly referred to the misery of society […] if anyone other than Mīsāqiyah had produced it, the film would undoubtedly have been banned.” Hasan Sharīfī, Pīshkisvatān-i sīnima-yi Īrān [The Founders of Iranian Cinema] (Khalīliyān Publishing, Tehran, 2006), PAGE NUMBER

It is also important to note that the violence found in the American films mentioned earlier contributed to an escalation of aggression and brutality in Iranian cinema. The vicious cycle of violence and revenge has remained a persistent theme in the films of both countries—a theme that also finds justification in broader historical and social contexts. As Peter Chelkowski observes, “Violence plays a prominent part […] This was also more acceptable to the religious element […] The use of physical strength in the service of the poor, wronged and oppressed has been a traditional them in Iranian culture for millennia.”45Peter Chelkowski, “Popular Entertainment, Media, and Social Change in Twentieth-Century Iran,” in The Cambridge History of Iran, vol. 7, ed. Peter Avery, Gavin Hambly, and Charles Melville (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 796.

Figure 26: A still from Scarecrow (1973) in Sīnimā 52 magazine (December 1973).

Within this framework, violence is not depicted as gratuitous or nihilistic, but rather as a form of moral resistance—a symbolic act of redress against injustice. This cultural acceptance extends to the theme of revenge, which is equally embedded in Iranian storytelling traditions. As Peter Chelkowski observes, “Revenge is a traditional Iranian them and greatly utilized by Iranian filmmakers […] Revenge is carried out mainly by the male members of a family or tribe.”46Peter Chelkowski, “Popular Entertainment, Media, and Social Change in Twentieth-Century Iran,” in The Cambridge History of Iran, vol. 7, ed. Peter Avery, Gavin Hambly, and Charles Melville (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 796.

These narrative patterns not only resonate with audiences steeped in epic traditions like the Shāhnāmah but also articulate modern societal grievances, ensuring their enduring presence in Iranian cinema.

![Figure 27: The title page of an article from Fīlm va Hunar (Film and Art), titled “Khushūnat bīdād mīkunad [Violence Reigns Supreme],” which explores the growing presence of violence in contemporary cinema during the 1970s.<sup class="modern-footnotes-footnote " data-mfn="4" data-mfn-post-scope="0000000019083a7300000000535f084f_18572"><a href="javascript:void(0)" role="button" aria-pressed="false" aria-describedby="mfn-content-0000000019083a7300000000535f084f_18572-4">4</a></sup><span id="mfn-content-0000000019083a7300000000535f084f_18572-4" role="tooltip" class="modern-footnotes-footnote__note" tabindex="0" data-mfn="4">Suzanne Darci, “Khushūnat bīdād mīkunad,” Fīlm va Hunar (April 13, 1972): 20,21.</span>](https://cinema.iranicaonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Picture1-17.png)

Figure 27: The title page of an article from Fīlm va Hunar (Film and Art), titled “Khushūnat bīdād mīkunad [Violence Reigns Supreme],” which explores the growing presence of violence in contemporary cinema during the 1970s.[mfn]Suzanne Darci, “Khushūnat bīdād mīkunad,” Fīlm va Hunar (April 13, 1972): 20,21.[/mfn]

Hollywood Reacts and Wakes Up: Protecting Its Business Interests in Iran

As Iran’s domestic film industry gained strength and prominence, American studios began to view it as a competitive threat.47“In 1948, only two Iranian films were produced and exhibited, whereas by 1970, this number had increased significantly to 81.” See, Sitārah-yi Sīnimā 788 (1972): 15 “American companies had endeavored to prevent the development of a national Iranian cinema: for instance, they had opposed four Persian-language films produced in Bombay between 1932 and 1935. However, at the time, there were only a handful of movie theaters in the country.”48Guy Hennebelle, Les Cinémas Nationaux Contre Hollywood [National Cinemas Against Hollywood] (Guy Gauthier, Éditions du Cerf, 2004), 238. Farrukh Ghaffārī (1922–2006), an influential Iranian filmmaker, film critic, and author, expressed deep bitterness and sorrow over this cultural loss.

As you know, Sipantā was the first filmmaker to create a Persian-language talking picture. With this achievement, he demonstrated that movies made in Persian about Iran and its people could deeply resonate with Iranian audiences and achieve great success. We could have had a major revolution in Iranian cinema during 1936-37. This progress was within reach, but it was crushed by exploitative foreign distributors who monopolized film imports. Our so-called “American brothers” joined in suppressing this movement. They not only stopped the production of Iranian films in India but simultaneously destroyed any potential for growth in Iran’s film industry.49Farrukh Ghaffārī, “Goftegu bā Farrukh Ghaffārī,” Tamāshā magazine 5 (1971): 16.

The collapse of Pārs Film—Iran’s first major studio—coincided with Hollywood-linked distributors strangling access to film stock and processing.50Pārs Film, Iran’s first major film studio, was Founded in 1928 by ‛Abdalhusayn Sipantā and Ardishīr Īrānī (Indian Parsi producer) and officially closed in July 1937. U.S. State Department records celebrate how American firms “discouraged Persian sound-films,” while British-run labs in India tripled processing fees. This wasn’t an accident; it was an economic siege.

Archival evidence confirms that Pārs Film’s 1937 collapse directly resulted from predatory pricing tactics at Bombay’s Imperial Film Laboratory—where development costs for Iranian filmmakers abruptly tripled following pressure from Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM). Trade correspondence reveals this was a deliberate strategy to eliminate nascent competition in Persia’s film market. As Farrukh Ghaffāri observes, “The Imperial Film Company of Bombay has, without justification, raised development fees from 300 to 900 rupees per reel this month. Our local agent confirms this followed a visit by MGM’s distribution chief, Mr. James Warner.”51Pārs Film Correspondence Collection, Box 12 (1936), Bahār Film Institute.

Another economic strategy employed to suppress Iran’s film industry involved U.S. distributors—allegedly in collaboration with local authorities—lobbying for exorbitant import tariffs on color film stock during the late 1940s. These prohibitive costs made it nearly impossible for Iranian filmmakers to shoot in color, despite color cinema becoming the international standard by the late 1960s. As a result, most Iranian films from this period were produced in low-quality black and white, a limitation that not only compromised aesthetic quality but also reinforced the perception of domestic cinema as outdated.52

By 1954 more than 50 percent of American features were made in color, and the figure reached 94 percent by 1970. David Cook, Robert Sklar, History of the motion picture, https://www.britannica.com/art/history-of-film/The-threat-of-television

While Iranian films of the 1960s–70s predominantly used black-and-white film due to economic constraints On this subject, Bahman Mufīd notes that, “Due to American productions and their desire to control the market, we were not allowed to shoot in color, even though films in color were being made in Africa. We wanted to purchase the necessary materials, but the Ministry of Culture refused to grant us permission. They told us that even they had left their materials in the ministry’s basement and were not allowed to use them.”53Bahman Mufīd (the renowned Iranian actor of the 1960s and 1970s) discussed the boycotts imposed by American producers and distributors during that period in a 2010 YouTube interview (no longer available online). A 1938 memo from the U.S. consul in Tehran boasts that Hollywood distributors had “successfully discouraged Persian sound-film ventures” to protect their market share.54An article on the state of Iranian cinema and ticket prices published in Rastākhīz newspaper (1978).

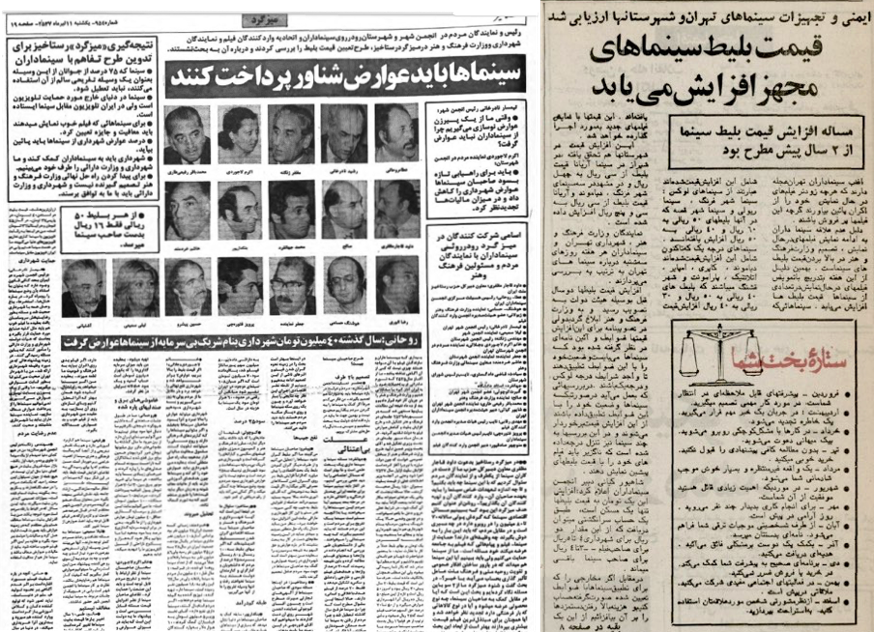

Figure 28: An article from Rastākhīz (July 1976) discussing the sharp increase in movie ticket prices.

Figure 29: An article from Rastākhīz (July 1978) discussing tax regulations affecting cinema theaters and ticket prices.

The tactics employed by Hollywood and American distributors to safeguard their market dominance extended beyond film production. American influence also significantly shaped the exhibition practices of Iranian cinemas. Cinemas that failed to prioritize the screening of American films were subject to government-imposed regulations, which included uniform increases in ticket prices.55“Between 1951 and 1976, American films dominated Iranian cinemas, maintaining an annual presence of 250 to 340 titles, a volume more than tenfold that of films imported from Italy, France, the United Kingdom, or the Soviet Union during the same period.” See the demographic table in the book of Masʿūd Mihrābī, Tārīkh-i sinamā-yi Īrān [The Cinematic History of Iran] (Tehran: Nashr-i Pīkān, 2004), 126.

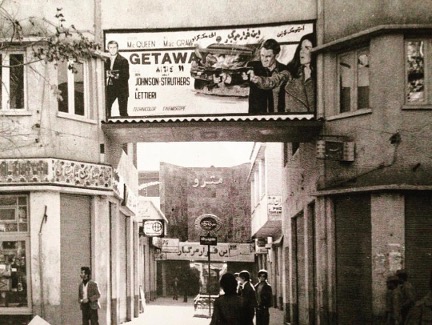

Figure 30: The Getaway (1972, dir. Sam Peckinpah) screened at a popular cinema in southern Tehran in 1974.

This policy disproportionately impacted working-class audiences, many of whom were already struggling with inflation and limited disposable income. For these patrons, attending the cinema became an increasingly unaffordable luxury. Given that Iranian film production relied heavily on ticket sales for financial survival—unlike Hollywood, which enjoyed access to diversified revenue streams through international distribution—this reduction in cinema attendance severely threatened the sustainability of local filmmaking. This economic pressure exemplifies the persistent challenges American film interests posed to Iranian cinema’s development, employing both direct competition and structural market advantages to constrain the industry’s growth from its earliest stages.

In the 1950s, a tax increase from 10% to 40% forced several studios to close their doors.56Ali-Naghi Assadi-Nik, “Les moyens de communication de masse (presse, radio, cinéma et télévision) en Iran,” (PhD thesis, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Paris, March 1973), 24. “In 1975, for reasons of national pride and anti-inflationary policy, the Shah himself briefly opposed the exorbitant demands of American companies to double ticket prices (a 100% increase), under threat of halting the export of American films.”57Yves Thoraval, Le cinéma du Moyen-Orient; Iran, Egypte, Turquie, 1896-2000 (Edition Seguier, 2000), 41.

Ultimately, the U.S. strategy was not merely an economic maneuver but a broader attempt to maintain dominance over the global film market. As one critic aptly noted, “Whenever a national cinema of a new genre rises on the international stage, challenging the American cinematic empire by its very existence […] whether with a velvet glove or a brutal grip, it makes every effort to neutralize it.”58Guy Hennebelle, Les Cinémas Nationaux Contre Hollywood [National Cinemas Against Hollywood] (Guy Gauthier, Éditions du Cerf, 2004), 115. This sentiment encapsulates the overarching narrative of American intervention in the global film industry: everything possible was done to safeguard Hollywood’s preeminent position by neutralizing potential competitors, regardless of the economic or aesthetic costs.

The expansion of television in Iran during this period added yet another layer of complexity. With state-run channels broadcasting a wide array of imported American shows and films, Iranian audiences were increasingly drawn to the convenience and affordability of home entertainment. This shift in viewing habits, while somewhat alleviating American concerns about direct competition from Iranian cinemas, further exacerbated the decline in theater attendance. As a result, domestic filmmakers faced even greater challenges, as the shrinking audience base placed further economic strain on local production efforts. As Guy Hennebelle notes, “since their films occupied seventy percent of the market, American companies did not bother to fight against an Iranian cinema whose techniques could not rival theirs and which held only twenty to thirty percent of the market.”59Guy Hennebelle, Les Cinémas Nationaux Contre Hollywood [National Cinemas Against Hollywood] (Guy Gauthier, Éditions du Cerf, 2004), 238.

A parallel case of economic and cultural restriction could be observed in Canada. In response to similar pressures from Hollywood studios, Canadian feature film production was significantly limited. As a result, Canada redirected its cinematic focus toward documentary filmmaking, which, being less commercially competitive, was more viable under the constraints of American dominance in the North American film market:

Canada’s concentration on documentaries was dictated by the fact that very few firms in Canada had the resources to become involved in film-making. Those who did engage in film-making did so in order to utilize a new and more persuasive form of communication. These early Canadian documentaries were sponsored commercials produced by either big business or government […] Due to these initial failures, private investors became leery of investing in other Canadian firms. without access to the distribution system, few Canadian films were seen, even though there was a supposed market for them.60

“In America, in order to guarantee their financial return, the major American firms involved in the production of motion pictures and equipment formed the Motion Picture Patents Association. The Motion Picture Patents Association (MPPA) was a powerful trust group which was formed in 1908 by Edison, Vitagraph, Biograph, Kalem, Lubin, Selig, Essanay, Pathe Exchange, Melies and Gaumont. These companies pooled together their patents on film, camera and projector technology. The MPPA then used their legal ownership of the patents to control the production, distribution and exhibition of motion pictures in the United States. Through pressure and intimidation, the MPAA either purchased or forced out of business all the exchanges in the U.S. with the exception of William Fox. Control was extended into Canada by the refusal of the MPAA to sell to Canadian producers and exchanges unless they were licensed by the MPAA. Through these monopoly actions, the MPAA was able to ensure that its members made a profit. In addition, MPAA members were assured of a market for their film production […] In 1916 George Brownridge, a Toronto film distributor and promoter, formed the Canadian National Features Company. Brownridge promoted this company as a nationalistic alternative to the American film industry. Nationalistic sentiment was high in Canada at this time in part due to Canada’s involvement in the First World War. There was also a strong anti-American sentiment, likely influenced by the after effects of the 1911 federal election in which free trade with the Americans was strongly rejected. Film censorship boards had been established in Ontario, Quebec and Manitoba by 1911 and in British Columbia and Alberta by 1913. Among the first acts of these boards was the banning or censoring of films which contained “an unnecessary display of U.S. flags”. In addition, the American MPAA had recently been dissolved by the U.S. courts. The combination of all of these factors likely lead Brownridge to believe that this was the opportunity to establish a film production industry in Canada.” Greg Eamon, “The Origin of Motion Picture Production in Canada,” canadianfilm.ca, January 10, 2022, accessed 11/06/2025, https://canadianfilm.ca/2022/01/10/the-origin-of-motion-picture-production-in-canada/

History records many unsavory incidents between Canadian independents and MPAA directed goons. For examples, see Janet Wasko, Movies and Money: Financing the American Film Industry (Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corporation, 1982); also Manjunath Pendakur, Canadian Dreams & American Control (Toronto: Garamond, 1990).

Hollywood’s Strategic Retreat from Low-Budget National Cinemas

Faced with the rise of national film industries in countries such as Iran, India, Egypt, and Turkey, American film companies gradually scaled back their efforts to suppress these burgeoning competitors.61“The cost of legal enforcement against these ‘copycat industries’ (notably Bombay and Istanbul-based producers) now exceeds projected revenue losses from their competition. Recommendation: Redirect anti-piracy funds to Arab markets where returns justify expenditure.” See, Toby Miller, Nitin Govil, John McMurria, Richard Maxwell, and Ting Wang, Global Hollywood 2 (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019), 89. This memo proves Hollywood’s deliberate withdrawal from Iran was not due to cultural respect, but a cold cost-benefit analysis favoring oil-rich Arab markets. See also Complete the citation Hollywood’s Secret Strategy: Paramount’s 1969 Memo on Abandoning Anti-Piracy Efforts in Iran. This strategic retreat was prompted by two key factors.

First, the sheer volume of emerging productions made control impractical. As regional film industries expanded, imitation became widespread. As Muhammad ‛Alī Fardīn observed, “More and more films were being made […] nearly all the stories were copied from the mass-produced Turkish, Indian, Arab, and Western films. With minor changes, someone would copy a story, then the same man would declare himself a director and insist on filming his plagiarized plot.”62‛Abbās Bahārlū, Sīnimā-yi Fardīn (Bi Ravāyat-i Muhammad ‛Alī Fardīn) (Edition Qatrah, 2000), 195. Second, Hollywood recognized that these low-budget productions—despite their popularity—posed little real threat to American cinematic dominance. On the contrary, their aesthetic and technical shortcomings often underscored the superior quality of Hollywood films. “Let them steal—their poverty makes better advertising for our superior quality.”63Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 3: The Islamicate Period, 1978–1984 (Duke University Press, 2011), 159. This quotation reflects a widespread view among Western distributors that piracy in markets like Iran inadvertently served as a form of promotion.

In some cases, American narratives were directly adapted by local filmmakers. One of the most notable examples, as mentioned earlier, was The Beggars of Tehran. Reflecting on the film, Fardīn remarked: “I was presented with a screenplay attributed to writer Hasan Siyāmī. Upon reading it, I enthusiastically approved the project, resulting in the commercially successful film […]. In reality, this production constituted an Iranian adaptation of Frank Capra’s American film Pocketful of Miracles (1961).”64‛Abbās Bahārlū, Sīnimā-yi Fardīn (Bi Ravāyat-i Muhammad ‛Alī Fardīn) (Edition Qatrah, 2000), 220.

From the American perspective, these imitative cinemas were seen as ideologically aligned rather than oppositional:

These Middle Eastern and Asian cinemas merely replicated, through different cultural frameworks, the ideological constructs of Westerns and American action films. As they ultimately reinforced, through alternative means, the hegemony of dominant classes allied with U.S. imperialism, excessive economic or political measures against them were deemed unnecessary.65Guy Hennebelle, Les Cinémas Nationaux Contre Hollywood [National Cinemas Against Hollywood] (Guy Gauthier, Éditions du Cerf, 2004), 239.

Despite its reliance on familiar narrative and stylistic conventions, Iranian national cinema steadily cultivated remarkable popularity among domestic audiences. These films resonated deeply within Iran, organically attracting a large viewership even without robust institutional protection. Iranian audiences (even contemporaneously) maintain strong affective ties to these cinematic narratives despite their technical or scriptural deficiencies, demonstrating the complex interplay between cultural proximity and cinematic quality.

“In Iran, while an economic market exists with quotas favoring domestic production, such protectionist measures prove superfluous as commercial Iranian films naturally enjoy public favor.”66Guy Hennebelle, Les Cinémas Nationaux Contre Hollywood [National Cinemas Against Hollywood] (Guy Gauthier, Éditions du Cerf, 2004), 240. Ultimately, the somewhat reluctant remakes of American films served, in part, as Siyāh Mashq (practice sheets), through which Iranian filmmakers could hone their technical and narrative skills, progressively articulating a distinctive cinematic language and aesthetic rooted in local cultural values, social realities, and collective consciousness. This process may help explain why domestic audiences increasingly gravitated toward these localized productions, favoring indigenous narratives and performers over imported Hollywood content.

Figure 31: A photograph of a movie theater in Tehran from the late 1950s, showing a large crowd of spectators outside, eager to obtain tickets for one of their favorite Fīlm-fārsī productions. The film featured is Tūfān dar Shahr-i Mā (Storm in Our Town), directed by Samū’il Khachikian, 1958.

On the night after watching Dances with Wolves, an elderly taxi driver took us home. Startled—as crowds still filled the streets at dawn—he asked:

“What’s happening?”

“Nothing special,” I replied. “They just showed a new American film.”

He slammed the brakes abruptly.

“An American film?”

His voice carried both surprise and nostalgia.

“I used to watch films all night long—from midnight until sunrise. That was before the Revolution, during the golden age of Iranian cinema. I saw every Fardīn films, all of Nāsir Malak-Mutī‛ī’s works, and Bayk Īmānvirdī’s, and Vahdat’s, and Bihrūz Vusūqī’s…”

His voice grew thick.

“But Fardīn—Fardīn was magic.67Muhammad ‛Alī Fardīn (1931-2000) was one of the most iconic and beloved actors in pre-revolutionary Iranian cinema (Fīlm-fārsī), known for his roles in action-packed melodramas and romantic films. He was also a champion wrestler before becoming an actor. Fardīn became a superstar in the 1960s and 1970s, often playing charismatic, tough, yet kind-hearted heroes who fought injustice. He remains a cultural icon in Iran, often referred to as “Sultān-i Qalb’hā” (King of Hearts). There will never be another like him. He was truly the greatest.”

As we drove through Tehran’s waking streets, he began singing softly, his voice trembling with memory:

“Sultān-i Qalbam tu hastī…”68“You are the king of my heart, yes, you are…” In Sultān-i Qalb’hā (1968), directed by Muhammad ‛Alī Fardīn, Fardīn’s character performs the title song “Sultān-i Qalbam” during a key emotional moment, blending the film’s themes of romance and social hardship. The song became a national hit, cementing Fardīn’s status as Iran’s “King of Hearts.”

At Vanak Square, he stopped to collect another fare. Then jabbed a finger at the dark:

“See that shop? The one with the Kashan carpets displayed in the window?”

He looked at us sadly.

“Fardīn’s shop. Our greatest national actor reduced to selling carpets to survive. What a shame… What a shame!”

The taxi lurched forward, his voice trailing the melody like exhaust fumes—faint, persistent, dissolving into Tehran’s dawn.

Figure 32: Fardīn at his shop in Vanak Square, Tehran, during the early 1990s

Cite this article

This article traces the shifting relationship between American cinema and Iran’s film industry from the 1940s up to the 1979 Revolution, focusing on how Hollywood shaped the landscape of Iranian film culture while limiting its independent growth. Drawing on archival records, censorship files, and close readings of selected films, it explores how U.S. studios—supported by Cold War cultural diplomacy—secured a dominant position in Iranian theaters while sidelining local productions. The piece revisits key moments such as the collapse of Pārs Film in 1937 after MGM-influenced development fees tripled overnight, and the impact of import tariffs that kept Iranian filmmakers reliant on black-and-white stock well into the color era. It also looks at how Iranian cinema responded—through imitation, adaptation, and later, critique. From the fīlm-fārsī remakes of Hollywood plots to the New Wave’s darker and more politically charged narratives, the article follows how American influence was absorbed, resisted, and reshaped. It ends with the 1991 Fajr screening of Dances with Wolves, seen through the eyes of Iranians who remember pre-Revolution cinema with a mix of longing and loss. Hollywood’s presence in Iran, the article suggests, left behind a complicated memory—part inspiration, part interference.