Farīdūn Rahnamā’s Filmic Utopia in Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother

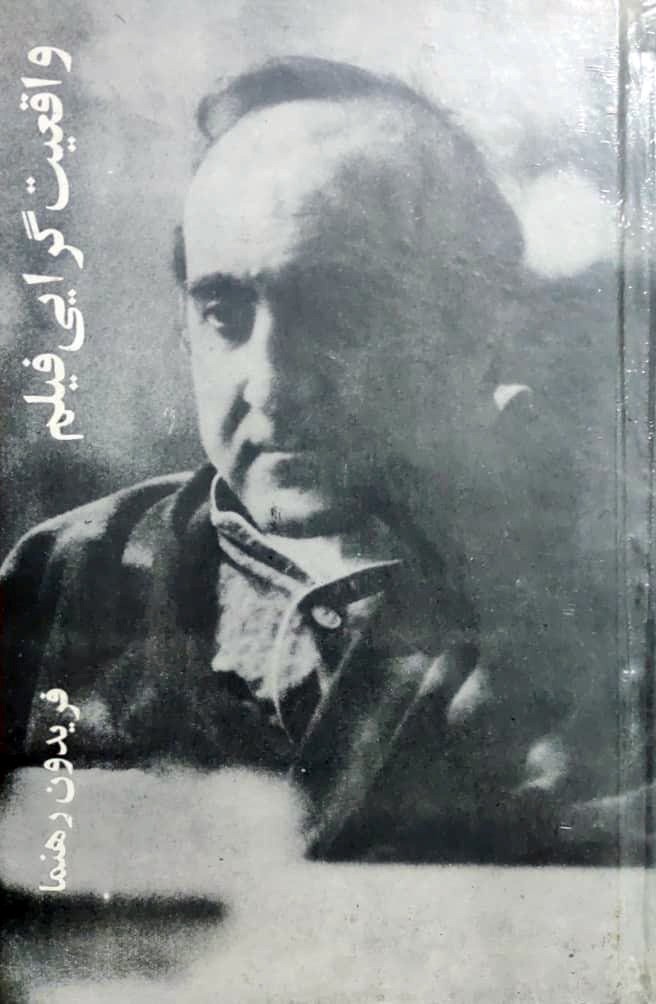

Figure 1: Poster for the film Pisar-i Īrān az Mādarash Bī-ittilāʿ Ast (Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother), directed by Farīdūn Rahnamā, 1976.

Introduction

Farīdūn Rahnamā’s Pisar-i Īrān az Mādarash Bī-ittilāʿ Ast (Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother, 1976) stands as a vital, if underexplored, artifact of Iranian modernist cinema. In this ambitious and highly symbolic work, Rahnamā interrogates the fractured relationship between contemporary Iranian identity and the country’s mytho-historical past. The film follows a young playwright and director who struggles to finance and stage a new theatrical production—a historical drama set during Iran’s Ashkānid (Parthian) period, which lasted from approximately 247 BC to 224 AD. As he attempts to bring his vision to life, he encounters resistance on several fronts: financial constraints, ideological disagreements, and personal tensions.

This film, Rahnamā’s second and final feature before his untimely death at the age of forty-five in 1975, continues the thematic exploration initiated in his earlier works, including the poetic documentary Takht-i Jamshīd (Persepolis, 1960) and the experimental feature Siyāvash dar Takht-i Jamshīd (Siyavash in Persepolis, 1965). In all three, Rahnamā is less concerned with narrative cohesion than with evoking a certain spiritual and philosophical crisis—namely, the loss of historical continuity and the fragmentation of Iranian identity in the face of modernization.

In Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother, a young director writes a play about faith during the Parthian (Ashkānid) era, with the intention of staging it in collaboration with a theater troupe. His thirst for exploring the fabric of history creates a conflicted situation for him. His girlfriend and fellow theater collaborator believes that one cannot pursue such a quest without abandoning personal attachments. The young man puts all his effort into staging the play, but the troupe members, protesting his authoritarian behavior as a director, write a letter demanding that the play be made more populist and stripped of its aristocratic elements. After parting ways with the troupe, he and his girlfriend decide to stage the play on their own.

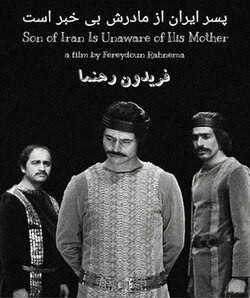

Figure 2: A still from the film Pisar-i Īrān az Mādarash Bī-ittilāʿ Ast (Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother), directed by Farīdūn Rahnamā, 1976.

A poet, thinker, and one of the seminal figures of the Iranian New Wave, Rahnamā’s work is distinguished by its rejection of strict boundaries between myth, history, and the present. In Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother, this refusal to draw clean lines manifests formally and thematically. Mythology and history are not merely evoked as subject matter; they are integrated into the very fabric of the film’s narrative structure and visual symbolism. The result is a dense, reflexive meditation on the impossibility of staging history in the modern world and on the alienation of the Iranian artist from both past and present. As in his earlier film Siyavash in Persepolis, the layering of ancient mythology onto contemporary settings suggests that these myths remain active, even if not always visible, in the modern psyche.

Filming began in 1969, but it took nearly five years to complete, with the film ready for release in 1974. It was first screened in June 1975 at the Cinémathèque in Paris, introduced by Henri Langlois—the director of the Cinémathèque and a prominent French film critic—and then later that July at the Tūs Festival in Iran.

Narrative Structure in Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother

In Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother, Farīdūn Rahnamā constructs a dual-layered narrative that unfolds across two interwoven planes. One layer focuses on the rehearsal of a historical stage play about the Parthians, following the actors’ performances and their engagement with the mythic past. The second, more intimate layer traces the personal life and artistic struggles of the director—an alter ego for Rahnamā himself—as he attempts to realize his ambitious theatrical vision amid growing resistance from his collaborators. The actors, objecting to what they perceive as the aristocratic tone and elitist themes of the play, push for a more accessible and commercially oriented production. Unwilling to compromise his artistic principles, the director refuses these demands, ultimately allowing them to leave the project.

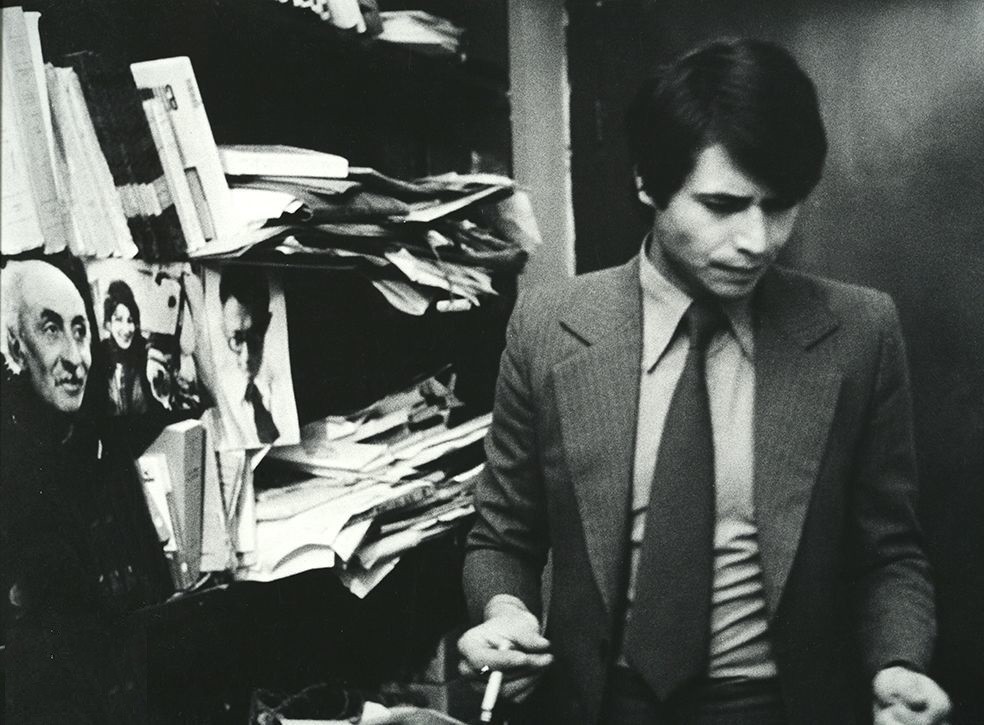

Figure 3: Sādiq Muqaddasī and Rizā Zhiyān in a scene from the film Pisar-i Īrān az Mādarash Bī-ittilāʿ Ast (Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother), directed by Farīdūn Rahnamā, 1976.

The film shifts fluidly between these two dimensions: between performance and reality, myth and modernity, history and the present. To mark these distinctions, Rahnamā uses a striking formal device: color. In a deliberate inversion of cinematic convention, the rehearsal scenes, representing the imagined or mythologized past, are presented in color, while the director’s everyday life, shot in grainy black and white, reflects the somber texture of contemporary existence. This use of color inversion emphasizes how the past, feels more vivid, alive, and aspirational than the fragmented and disenchanted present.

This approach contrasts with Rahnamā’s earlier film Siyavash in Persepolis, where color and black-and-white footage serve a more conceptually layered function. There, color enters only through the lens of German documentarians filming the ruins of Persepolis, signifying an exoticizing, external gaze, while Rahnamā’s own footage, representing an internal, indigenous perspective, remains in black and white. In Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother, however, color is used more literally to mark shifts in narrative mode rather than in perspective or ideology.

At the heart of the film lies a series of tensions: between the artist’s elevated historical imagination and the political or emotional demands of the present; between intellectual idealism and the pragmatic expectations of his audience; and between the desire to preserve cultural memory and the difficulty of making it resonate in a contemporary context. These tensions manifest through interpersonal conflicts: the cast and crew challenge the director’s aristocratic treatment of history and push for a more accessible, populist version of the play. His girlfriend and theatrical partner, Rushanak, expresses skepticism about the relevance of his historical fixation, questioning whether one can truly pursue liberty or meaning through the distant past while ignoring the emotional urgencies of the present.

Rather than culminating in a completed theatrical performance, the film ends with fragmentary images and symbolic gestures. In one of the final scenes, Rushanak appears alone onstage, delivering a poetic monologue about their collective struggle for liberty ⸺ a moment that blurs the boundary between political theater and personal testimony.1Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother, dir. Farīdūn Rahnamā (Iran, 1976), 01:04:21-01:05:48.

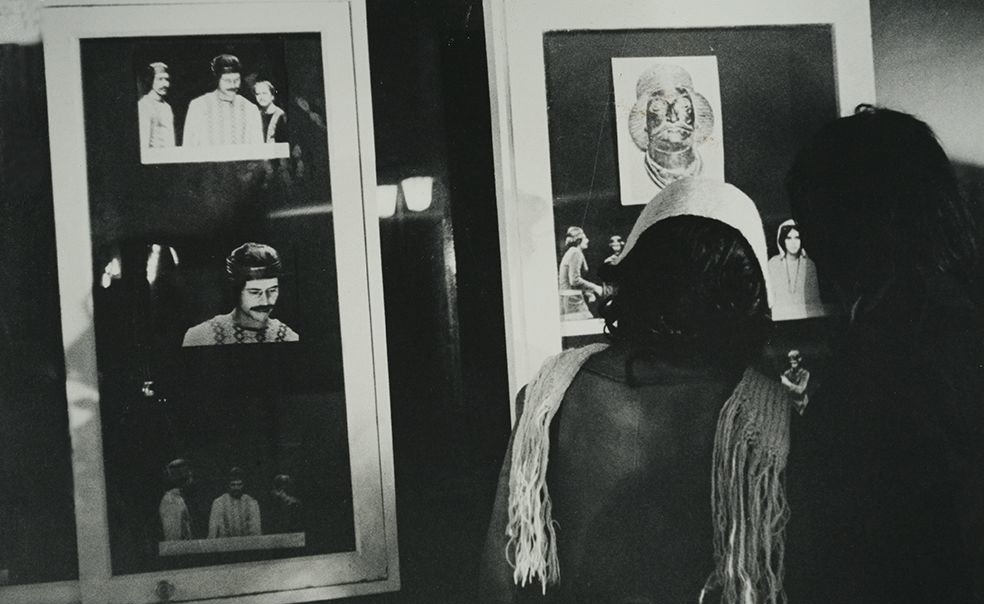

Figure 4: Āhū Khiradmand as Rushanak in a scene from the film Pisar-i Īrān az Mādarash Bī-ittilāʿ Ast (Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother), directed by Farīdūn Rahnamā, 1976.

The audience’s reaction is notably ambivalent: while some applaud her speech, others rise from their seats and exit the hall in protest, voicing disapproval or disengagement. This mixed response becomes a mirror of the divided reception Rahnamā himself anticipated or experienced between admiration and rejection, resonance and resistance. Meanwhile, the director, dressed in ashk or the Parthian commander’s costume, is seen in a phone booth receiving a long-distance call about his play. These closing moments deny any narrative closure. The play is neither fully staged nor entirely abandoned. Instead, the viewer is left with echoes, symbols, and unresolved gestures. The telephone call, possibly from abroad, adds a layer of irony, suggesting the external validation the director never receives at home. The boundary between performance and reality, between myth and mundane life, remains porous and unsettled.

Figure 5: A still from the film Pisar-i Īrān az Mādarash Bī-ittilāʿ Ast (Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother), directed by Farīdūn Rahnamā, 1976. Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0zoNXukBHk0 (01:06:59).

Thus, Rahnamā’s narrative structure resists linear resolution. It is composed of ruptures, disjunctions, and reflexive folds. The director does not triumph or fail in any conventional sense. Rather, he remains suspended between a vanished past and an ungraspable present. The mythic aspirations of his play contrast starkly with the banal struggles of production, mirroring the broader condition of Iranian intellectuals caught between nationalism, nostalgia for cultural grandeur and the alienation of modern life. This dynamic is explored in Ali Mirsepassi’s Intellectual Discourse and the Politics of Modernization (2000), where he examines the intellectual’s role in negotiating between mythic national narratives and the socio-political realities of contemporary Iran. Mirsepassi notes the deep nostalgia among Iranian intellectuals for the “lost world of the past” and a yearning for retribution against those perceived to have destroyed it. He writes: “The anti-Western nostalgia among Iranian intellectuals was symbolized through the concept of Gharbzadegi (Westoxication). The romanticism of the Islamic and Iranian traditions induced a very hostile reaction against modernization as a Western-centered project. The romanticism of the Gharbzadegi discourse embodied an image of modernity that could only be realized in the context of Iranian national settings.”2Ali Mirsepassi, Intellectual Discourse and the Politics of Modernization (Cambridge University Press, 2000), 77.

Similarly, Mehrzad Boroujerdi, in Iranian Intellectuals and the West (1996), analyzes how modern Iranian thinkers constructed a nativist vision of an idealized, uncorrupted culture free from Western influence. According to him, “The knowledge of self was attained through a noncritical, nostalgic appropriation of one’s own historic past. Whereas some took refuge in the glory of pre-Islamic Persia, others idolized the country’s religious and mystical traditions.”3Mehrzad Boroujerdi, Iranian Intellectuals and the West (Syracuse University Press, 1996), 135. In his assessment, “Its nostalgia for the past, attachment to things native, idealization of identity, and ethical-romantic rejection of modernity are all problematical.”4Mehrzad Boroujerdi, “Gharbzadegi: The Dominant Intellectual Discourse of Pre- and Post-Revolutionary Iran,” In Iran: Political Culture in the Islamic Republic, ed. Samih K. Farsoun and Mehrdad Mashayekhi (Routledge, 2005), 35.

These frameworks help situate the film’s inner conflict within a larger cultural discourse on artistic and ideological dislocation.

Identity Crisis and Alienation

Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother delves deeply into the crisis of identity in modern Iranian society, positioning this existential disorientation in direct relation to the nation’s fragmented relationship with its mytho-historical past. Farīdūn Rahnamā’s approach is neither nostalgic nor didactic; instead, it is self-consciously reflective, often blurring the lines between history and myth, fiction and documentary, performance and reality. His protagonist, the young playwright, emerges not only as an individual artist but as a symbolic figure, a proxy for the modern Iranian intellectual seeking coherence in a disjointed cultural landscape.

The title Pisar-i Īrān az Mādarash Bī-ittilāʿ Ast (Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother) is an evocative allegory drawn from a real newspaper headline: a woman searching for her lost son, or perhaps vice versa. In Rahnamā’s poetic recontextualization, this literal headline becomes a metaphor for the fractured relationship between modern Iranians and their cultural and historical roots. The mother becomes the motherland, Iran, and the son who has no news of his mother stands in for modern Iranians who, estranged from the maternal figure of their cultural origins, wander in search of a history that no longer speaks to them. This disconnection is the emotional and philosophical core of the film. Rahnamā explores the alienation of the Iranian intellectual in a society that no longer recognizes its own history, let alone its mythic consciousness. In this sense, Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother serves as a sequel or spiritual continuation of his earlier film Siyavash in Persepolis. In both, the central figure is a disillusioned artist-intellectual, a stranger to his own culture, misunderstood by his peers, and tragically out of step with a society that has lost the ability to remember.

By depicting rock-and-roll music, Western fashion, and a generation immersed in foreign habits, Rahnamā dramatizes the dissonance between past and present. His critique is not moralistic but mournful, a recognition that history has become a museum artifact, removed from the living memory of the people. Museums and theater stages are now the only places where Iran’s myths and epics continue to exist.

Figure 6: Sādiq Muqaddasī, Rizā Zhiyān, and Āhū Khiradmand in a scene from the film Pisar-i Īrān az Mādarash Bī-ittilāʿ Ast (Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother), directed by Farīdūn Rahnamā, 1976.

One of the central themes of the film is the dissonance between national memory and lived experience. The playwright’s desire to stage a grand historical drama from the Ashkānid period represents a longing to reclaim a pure, heroic past. However, this desire is met with skepticism by those around him. His partner’s reminder that one cannot sever ties with daily interpersonal realities when engaging with the past gestures toward a larger philosophical argument: history is not an abstract entity to be resurrected at will, but a living, contested domain entangled with contemporary ethics and relationships.

Rahnamā’s Utopian Vision and Historical Longing

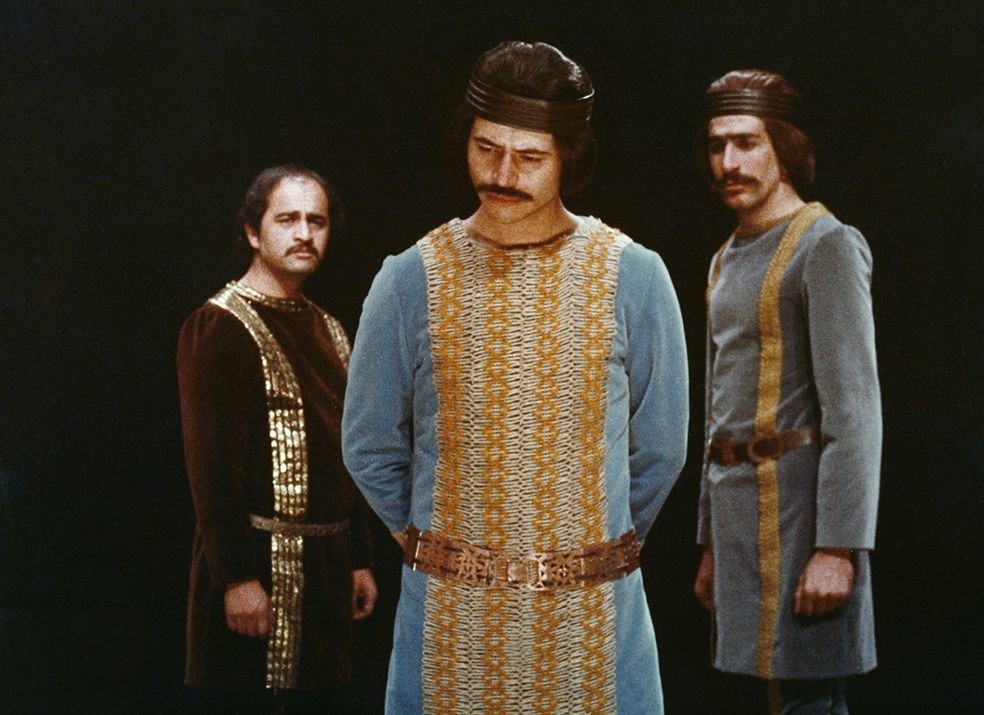

The opening sequence of Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother immediately situates the film within a utopian and historiographical framework that was characteristic of many Iranian New Wave filmmakers during the 1960s and 1970s. The film begins with a static shot accompanied by the sound of a typewriter. A hand (presumably Rahnamā’s) places photographs of ancient Iranian monuments such as Persepolis on a desk, followed by images of contemporary rural villagers. This sequence visually bridges Iran’s mythic past with its present, signaling the film’s underlying concern with historical continuity and rupture.

Figure 7: A still from the film Pisar-i Īrān az Mādarash Bī-ittilāʿ Ast (Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother), directed by Farīdūn Rahnamā, 1976. Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0zoNXukBHk0 (00:00:46).

Layered over these images is a voiceover conversation between two unidentified men. One voice, likely Rahnamā’s, expresses a curiosity about Iran’s fate after its defeat by Alexander the Great. The other voice replies with resigned insistence: “It’s all the same. I’ve been saying for years, it’s all the same.” This dialogue encapsulates Rahnamā’s melancholic view of Iran’s historical destiny: a cycle of repeated invasions, cultural fragmentation, and the lingering ruins of a once-glorious civilization.

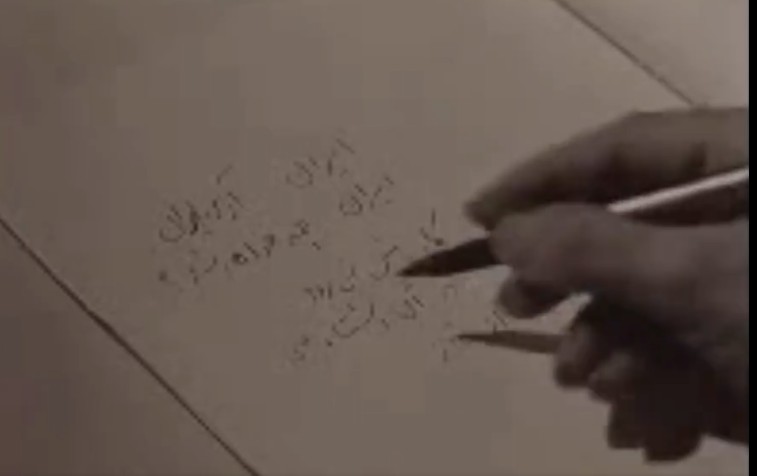

Shortly afterward, Rahnamā’s hand enters the frame again to write a quotation from René Grousset: “Iran is the threshold of the West and also the threshold of the East, a bridge between East and West.”5Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother, dir. Farīdūn Rahnamā (Iran, 1976), 00:02:18-00:02:40. This statement captures Rahnamā’s utopian imagination of Iran as a civilizational mediator, a lost cultural fulcrum positioned between two worlds. The gesture reflects a nostalgic idealism about Iran’s historical role and signals the broader intellectual mood among Iranian New Wave filmmakers, who frequently sought a “lost object” in the nation’s past, a utopian essence that could inspire a cultural and political future. This outlook extended beyond cinema, resonating with the historical consciousness of many Iranian intellectuals during the Pahlavī era who desired to reconnect with a pre-Islamic grandeur while simultaneously modernizing the nation.

Figure 8: A shot of Farīdūn Rahnamā’s hand as he writes notes representing the filmmaker’s presence within the narrative. Pisar-i Īrān az Mādarash Bī-ittilāʿ Ast (Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother), directed by Farīdūn Rahnamā, 1976.

However, while Rahnamā’s vision intersects with the Pahlavī state’s own efforts to revive the glory of ancient Persia, exemplified by the 2500-year celebration of the monarchy, it remains distinct in tone and intent. Unlike the regime’s often chauvinistic and instrumental use of history, Rahnamā’s engagement with the past is more reflective and existential. His approach mourns a fractured identity and critiques both Western hegemony and local loss of agency.

Notably, Rahnamā universalizes this identity crisis. Within the play that unfolds inside the film, a Greek general confesses to his Persian counterpart that the Greeks are also facing decline. Their cultural dominion is being displaced by the “uncivilized” and rising Romans. Here, Rahnamā expands the theme of civilizational decline beyond Iran, suggesting that imperial decay and historical displacement are universal conditions rather than uniquely Iranian. This mirrors the anxieties of a postcolonial world grappling with fractured identities and the specter of lost empires.

Nativism, Otherness, and the Search for Self

The historical play that the director intends to perform is not coincidental. It marks a symbolic moment of cultural confrontation: the first major point at which Iranian and Western civilizations met in conflict and negotiation. The Greeks in the play represent the West; the Parthians stand for a struggling Iranian identity attempting not merely to resist but to comprehend the “other” in order to understand itself. In this framework, history is not treated as a distant object of curiosity, but as a living metaphor for the dilemmas of the present. In one pivotal moment, a Greek commander addresses the Parthian leader with biting clarity: “You are defending the people who see you as a stranger and they obey us. You are defending an imaginary freedom.”6Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother, dir. Farīdūn Rahnamā (Iran, 1976), 00:43:53-00:44:23. This line crystallizes Rahnamā’s diagnosis of the modern Iranian condition: a citizen cut off from their own culture, who neither resists foreign domination nor recognizes the worth of native traditions. The protagonist identifies deeply with his historical character, much like Siyāvash in Siyavash in Persepolis and, disturbingly, feels more affinity with the foreign commanders than with his own people. In another striking line, a Greek character warns, “The rule in this land has been and is based on dictatorship, and this is why this land is going to be destroyed; don’t you ever forget it.” These moments of inter-historical dialogue transcend period authenticity, functioning as philosophical meditations on Iran’s cyclical political failures and cultural amnesia.

Figure 9: Sādiq Muqaddasī in a scene from the film Pisar-i Īrān az Mādarash Bī-ittilāʿ Ast (Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother), directed by Farīdūn Rahnamā, 1976.

Crucially, Rahnamā’s engagement with history is never chauvinistic. Though passionately committed to the preservation of Iranian cultural identity, he resists any essentialist or exclusionary nationalism. He was no xenophobe; he spent years in Europe, wrote and published in French, and maintained a philosophical openness to the West.7Farīdūn Rahnamā’s intellectual orientation reflected a rare synthesis of Iranian cultural consciousness and Western philosophical inquiry. In addition to his filmmaking, Rahnamā wrote and published poetry in French, including Ode a la Perse (1951), Ode au monde (1955), Poèmes anciens (1959) and Chant de délivrance (1968), works that reveal both his literary ambition and his engagement with broader intellectual currents. Unlike many intellectuals of the 1960s, who adopted a resolutely anti-Western stance, Rahnamā was not anti-Western; rather, he believed in the possibility of coexistence and dialogue between Iranian and Western intellectual traditions, a theme that runs throughout his cinematic work. While deeply concerned about the erosion of Iranian historical and cultural identity, Rahnamā sought to raise critical questions about national memory and belonging. Rahnamā, though sympathetic to critiques of superficial Westernization, avoided the essentialist dichotomies espoused by figures such as Jalāl Āl-i Ahmad. Like Āl-i Ahmad, he was troubled by the disorienting effects of unrooted Western influence on Iranian society, yet his response was more philosophically measured. His engagement with the West did not signal an uncritical embrace but rather a dialogical openness grounded in introspection and cultural self-awareness. As Henri Corbin observed, Rahnamā’s position was complex: he remained firmly anchored in the metaphysical and spiritual traditions of Iran while remaining intellectually receptive to Western thought, seeking synthesis rather than rejection.8See “Chihil sāl pas az khāmūshī-i Farīdūn Rahnamā,” Iranian Studies, 19 March 2016, accessed August 09, 2025, https://iranianstudies.org/fa/1394/12/29/. In one poignant moment in the film, the protagonist asks: “In this land, I saw oblivion that covered everything. Where is Iran? What is Iran?” These are not rhetorical questions; they are existential ones. Through such inquiries, Rahnamā underscores the dangers of historical amnesia and the neglect of cultural identity. In this sense, Rahnamā is more of an “archaeological” thinker than a nationalist. He digs into layers of historical sediment not to glorify them but to understand what has been lost, what has been forgotten, and what might still be recovered through art. His cinema is a form of intellectual excavation. His characters, alienated and misunderstood, embody a deeper social malaise: the estrangement of a society from its own historical consciousness.

Figure 10: Sādiq Muqaddasī as the director in a scene from the film Pisar-i Īrān az Mādarash Bī-ittilāʿ Ast (Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother), directed by Farīdūn Rahnamā, 1976.

Rahnamā’s Meta-Cinematic Approach and Self-Reflexivity

The protagonist of Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother, a young playwright and director, serves as a surrogate for Farīdūn Rahnamā himself. Fascinated by the Ashkānid (Parthian) period, he is determined to stage a historical drama about the conflict between the Parthians and the Greeks. Rahnamā’s treatment of this material is deeply meta-cinematic: the film continually collapses the boundary between fiction and reality, performance and process, history and the present. The viewer sees the protagonist develop, rehearse, and attempt to stage a play, while the world around him echoes and critiques the very themes of the performance.

This layering of theatricality and everyday life constructs a self-reflexive narrative framework. It becomes a conversation between fact and fiction, between past and present, between history and the routines of contemporary life. What emerges is not only an intellectual exploration of history but a psychological portrait of an artist struggling with his environment, his collaborators, and himself. Rahnamā inserts himself into the film in multiple, deliberate ways. His physical hand appears writing quotations and poetic fragments. Rahmana himself dubs the voice of the protagonist. The protagonist’s room is Rahnamā’s actual room. These self-insertions function not just as metafictional gestures, but as personal confessions. They reflect his vulnerability and isolation as a filmmaker whose experimental methods and historical themes stood in opposition to both commercial cinema and the dominant ideological currents of the time. In the context of 1960s Iran, these dominant currents were shaped by a growing anti-Western sentiment, most prominently articulated by intellectual figures such as Jalāl Āl-i Ahmad and ‛Alī Sharī‛atī. Āl-i Ahmad’s concept of “Gharbzadigī” (Westoxification) critiqued Iran’s cultural and political dependency on the West, calling for a return to indigenous values.9See Jalāl Āl-i Ahmad, Occidentosis: A Plague from the West, trans. by R. Campbell (Berkeley: Mizan Press, 1984). Similarly, Sharī‛atī’s writings promoted a radical Islam that rejected both Western liberalism and Marxist materialism in favour of an ideologically authentic Iranian-Islamic identity. These prevailing discourses, which emphasized cultural authenticity and political resistance to Western influence, are explored in depth by Mehrzad Boroujerdi in Iranian Intellectuals and the West (1996), and by Ali Mirsepassi in Intellectual Discourse and the Politics of Modernization (2000). In this intellectual climate, Rahnamā’s formally avant-garde and historically reflective cinema, rooted neither in nationalist nostalgia nor in religious revivalism, found itself at odds with the prevailing discourses.

Rahnamā’s self-awareness extends beyond stylistic devices and becomes a critical dialogue with his own society. Throughout the film, members of the theater troupe, including actors and producers, voice their dissatisfaction with the director’s approach, criticizing his lofty treatment of historical material, the aristocratic tone of the play, and his disconnection from ordinary people. These characters effectively voice the potential criticisms that Rahnamā anticipated from his contemporary audience. For instance, Rizā Zhiyān, who plays the Iranian general in the play, openly objects to the elitist tone of the script, exclaiming, “You know what? This play is about aristocracy, the same aristocracy that’s crushed the people.”10Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother, dir. Farīdūn Rahnamā (Iran, 1976), 00:54:40-00:54:50. In protest, he storms off stage. In another scene, the theater’s producer and other members of the crew attempt to oust the director, arguing that the play must be reworked into something more populist and hopeful. They want the aristocratic hero to be rewritten as a representative of the working class. The director responds with biting irony: “A coup against the director to make the play more populist. That’s democracy for you.”

Figure 11: Rizā Zhiyān objects to the elitist tone of the script. Still from the film Pisar-i Īrān az Mādarash Bī-ittilāʿ Ast (Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother), directed by Farīdūn Rahnamā, 1976. Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0zoNXukBHk0 (00:38:55).

These moments exemplify Rahnamā’s acute self-consciousness. He turns his own artistic dilemma into the subject of his film: an internal dialogue dramatized onscreen. This not only critiques the superficial populism of some leftist intellectual trends in 1960s–70s Iran, but also takes aim at the commodification and vulgarization of art under the guise of “relevance” or accessibility.

In another striking scene, a carpenter and friend of the director questions why he does not choose to stage a more contemporary play, something less expensive and more relatable. The director responds that the struggles of the Parthians are, in fact, deeply relevant to today’s Iran:

“What did the Parthians want? They wanted to improve the country.”

But the carpenter remains skeptical:

“That may be true, but no one listens. People today are too busy with their own problems.”

To which the director insists:

“It was the same back then. But the Parthians managed to make people understand.”

The carpenter challenges him:

“They were aristocrats, weren’t they?”

“So what?” the director replies.

“It matters. They didn’t know the people’s pain.” the carpenter says.

“And how do you know who understands the people’s pain?” the director counters.11Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother, dir. Farīdūn Rahnamā (Iran, 1976), 00:59:36-00:60:04.

Figure 12: The carpenter, acting as the director’s friend, poses a few questions to him. Still from the film Pisar-i Īrān az Mādarash Bī-ittilāʿ Ast (Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother), directed by Farīdūn Rahnamā, 1976. Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0zoNXukBHk0 (01:02:21).

This exchange encapsulates Rahnamā’s critique of binary thinking and political reductionism. The film refuses to simplify complex cultural and historical issues into easily digestible ideologies. Instead, it foregrounds the contradictions and ambiguities inherent in artistic expression, historical interpretation, and collective identity. Despite opposition and alienation, the protagonist stages his play in solitude, unadorned, unrecognized, yet uncompromised. This mirrors Rahnamā’s own fate. Though he completed Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother, it was never widely screened during his lifetime. Its unfinished premiere at the Cinémathèque Française, organized by Henri Langlois (the pioneer of film preservation and the founder and director of the Cinémathèque Française, remains a poetic metaphor for Rahnamā’s marginalized position in both Iranian and global cinema—a visionary whose self-reflexive voice was too complex, too layered, and too ahead of its time to be fully recognized during his life.

Stylistic and Visual Strategies

Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother marks a significant technical and stylistic evolution in Rahnamā’s filmmaking practice. Compared to his earlier experimental works such as Siyavash in Persepolis, this film demonstrates a more deliberate command of cinematic language, both in terms of visual composition and narrative architecture. While still deeply experimental and nonlinear, Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother reveals a more refined integration of form and content. It transforms into a film-essay, personal, discursive, and intertextual, evoking comparisons to the cinema of Jean-Luc Godard and Chris Marker. Like their works, Rahnamā’s film resists classical storytelling and instead builds meaning through collage, reflection, and juxtaposition.

One of the most compelling examples of Rahnamā’s symbolic visual design is the extended sequence set inside the National Museum of Iran. Here, the camera becomes almost anthropological, curious, searching, and restless. It lingers on ancient artifacts and statues, treating them not merely as historical objects but as signs waiting to be reinterpreted. The most poignant moment arrives when the camera pauses in front of the statue of a Parthian commander (ashk), majestic, silent, and missing a hand. This mutilated figure becomes a metaphor for a lost generation, a severed historical continuity. Yet, in a quiet cinematic counterpoint, the film persistently shows a hand (Rahnamā’s own) writing reflections throughout the narrative. This juxtaposition, the absent hand of history and the present, poetic hand of the filmmaker, suggests that others will take up the task left unfinished by the past. If history has faltered, then art, and perhaps cinema, may restore its gesture.

Figure 13: Statue of a Parthian commander (ashk), National Museum of Iran. Still from the film Pisar-i Īrān az Mādarash Bī-ittilāʿ Ast (Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother), directed by Farīdūn Rahnamā, 1976. Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0zoNXukBHk0 (00:05:40).

Rahnamā frequently employs long takes, static framing, and spatial fragmentation to create a mood of alienation and introspection. The theatrical scenes within the film, a play within a play, further enhance the meta-cinematic quality of the narrative. These inner performances, often stripped of elaborate sets and relying heavily on declamatory dialogue and stylized gesture, evoke a sense of ritual rather than conventional drama. They are not reconstructions of history but meditations on the impossibility of such reconstructions. Rahnamā’s camera is not merely observational; it is ontological. It asks questions by the way it frames space, by the rhythms of its edits, and by its insistence on detouring from expected narrative paths. He allows the camera to wander through physical and conceptual ruins alike. Interiors are filled with fragments of memory: old books, half-finished props, statues, and scripts, all symbols of a decaying or forgotten tradition. The modern world intrudes as noise and rupture: rock music, casual dancing, indifferent dialogue. This opposition between ruin and spectacle, between silence and noise, past and present, gives the film a uniquely essayistic texture.

The film’s self-conscious use of images, still photographs, documents, handwritten texts, and rehearsals extends Rahnamā’s investigation of history into a layered visual archive. These elements are not merely inserted for exposition but serve as interruptions and provocations. Rahnamā understands that history is never linear, and so his film reflects that epistemological uncertainty. The film intercuts moments from the play’s rehearsal with the protagonist’s solitary writing, the group’s chaotic interactions, and abstract images of ruins or museum objects. These intercut layers work against chronological cohesion, creating instead a spiral structure where every new image recalls a forgotten one, and every forward movement evokes a prior absence. Such nonlinearity, which might be considered disruptive in conventional cinema, here serves as a deliberate mode of inquiry. The film meditates on how memory works: it is fragmented, non-continuous, and full of gaps, and it models its narrative on that very structure. This was highly innovative in Iranian cinema at the time. Rahnamā was among the first Iranian filmmakers to engage history not just as subject matter, but as a formal problem. He constructs a space where the past is always returning, not as clarity, but as enigma.

Figure 14: A still from the film Pisar-i Īrān az Mādarash Bī-ittilāʿ Ast (Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother), directed by Farīdūn Rahnamā, 1976.

The film’s tone has often been described as preachy or overly didactic. Indeed, Rahnamā’s voice and the protagonist’s monologues contain direct philosophical commentary and rhetorical questioning. Yet this tone finds its proper place within the framework of the film-essay. The digressive, meditative narration (sometimes poetic, sometimes melancholic) functions not as exposition but as emotional argument. The self-referential narration, the poetry-like fragments written onscreen, and the direct address to themes of loss, identity, and national oblivion all contribute to the film’s internal consistency as a reflective, first-person cinema of ideas.

What also sets this film apart stylistically is its use of multi-modal audio-visual strategies. Rahnamā blends sound and image in complex ways, often layering ambient noise over still images or muting scenes of dialogue to let voiceover commentary take precedence. Historical documents are presented not to inform, but to disrupt. Photographs appear like ghosts. Theater props become relics. These juxtapositions resist linear storytelling, serving instead as prompts for reflection. In this way, Rahnamā expands the expressive possibilities of cinema in Iran at a time when such formal experimentation was rare. His attention to visual rhythm, sound design, and spatial composition reveals his maturity as a cinematic thinker by the time he made Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother. The editing, looser and more contemplative than in his previous films, creates space for philosophical detours and associative thinking. His lighting and framing also become more disciplined; there is a stark, almost sculptural quality to some of the interior shots, in which the protagonist is surrounded by piles of books, costume pieces, or ancient objects. These visuals further emphasize his position as both archivist and artist, caught between two worlds.

Rahnamā’s use of space also reflects his thematic concerns. Interiors are often claustrophobic, emphasizing the protagonist’s isolation. Exteriors, when they appear, are rarely idyllic. Instead, they are sparse and abstracted, functioning less as real environments than as symbolic extensions of the characters’ inner states. In this sense, space in Rahnamā’s cinema operates much like myth itself: displaced from time, charged with metaphoric resonance, and ultimately resistant to resolution. The stylistic accomplishments of the film lie in Rahnamā’s ability to synthesize personal experience, philosophical inquiry, and visual poetics. He develops a cinematic voice that is both introspective and outward-looking, deeply Iranian yet globally resonant. While his earlier films were more raw and tentative in their formal experimentation, Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother feels assured in its hybridity, fully embracing cinema as an intellectual and emotional language.

Conclusion

Based on his writings and interviews, Rahnamā seems to have regarded cinema as a profoundly meaningful and potentially transformative art form, an understanding that, in my view, reflects a deep intellectual and aesthetic commitment to its possibilities. Though his films may fall short in technical polish compared to the landmarks of global modernist cinema, they remain undeniably avant-garde and formally radical within the context of Iranian film history. Even today, works like Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother stand as bold and unconventional examples of cinematic experimentation. For Rahnamā, reality was never a fixed or singular construct. Like many modernist filmmakers, he viewed it as transient, layered, and elusive, always shaped by the filmmaker’s subjectivity. In his book Realism in Film, he challenges the idea of objective truth in cinema, arguing that each filmmaker, in pursuing realism, constructs a personal and unique reality, often divergent from dominant conventions.12Farīdūn Rahnamā, Vāqi‛īyyat-garā’ī-i fīlm [Realism in Film] (Tehran: Murvārīd Publication, 1972), 8. This philosophical stance is matched by his stylistic choices. For example, Rahnamā films the conversation between the young director and a carpenter friend in a single static long take, resisting classical editing or camera movement. This minimalist, contemplative mise-en-scène recalls the influence of Robert Bresson and Carl Theodor Dreyer, placing Rahnamā among the most radical auteurs of his time. Like Jean-Marie Straub or Pasolini, he treated cinema as a crossroad where theater, literature, poetry, and history converge.

Figure 15: Cover of Rahnamā’s book, Vāqi‛īyyat-garā’ī-i fīlm (Realism in Film).

According to Rahnamā, rather than allowing ideas to remain self-referential or purely theoretical, film serves as a medium through which thought becomes active and consequential in the real world. In Realism in Film, Rahnamā asserts that “film compels thought to truly come into being, to be born, and to enter the world—rather than revolve around itself or remain trapped in a futile cycle.”13Farīdūn Rahnamā, Vāqi‛īyyat-garā’ī-i fīlm [Realism in Film] (Tehran: Murvārīd Publication, 1972), 124. So, for Rahnamā, cinema has a unique ability to externalize abstract thought, transforming it into a tangible and socially engaged form.

Rahnamā’s work is deeply intertextual. His adaptations of historical and literary material are far from faithful reproductions. Rather, they are critical engagements that reframe these texts through a contemporary and often philosophical lens. This is evident in both Siyavash in Persepolis and Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother, where he integrates photographs, archival documents, and historical objects into the narrative, creating a fractured, modernist meditation on history, memory, and national identity. His films take the shape of cinematic essays, akin to works such as Jean-Luc Godard’s Masculin Féminin (1966) or Chris Marker’s Sans Soleil (1983). The didactic tone, while occasionally grating, aligns with the essayistic nature of his cinema.

Admittedly, Rahnamā’s films suffer from certain weaknesses, most notably exaggerated and at times artificial performances, poorly dubbed dialogue, and uneven pacing. These flaws can detract from the emotional immediacy and overall believability of his narratives. Yet, they should not overshadow the intellectual ambition and formal daring of his cinematic vision.

Rahnamā’s cinema may not offer polished narratives or widely accessible storytelling, but it embodies a rare courage to challenge the conventions of form, narration, and ideology. His refusal to conform to dominant cinematic codes and his commitment to poetic and philosophical inquiry make his work foundational to both Iranian New Wave cinema and the broader landscape of experimental filmmaking. Iran’s Son Is Unaware of His Mother is not only a historically significant artifact but also a living, breathing document of avant-garde resistance, an experimental film that remains unmatched in its ambition and singularity within Iranian cinema.