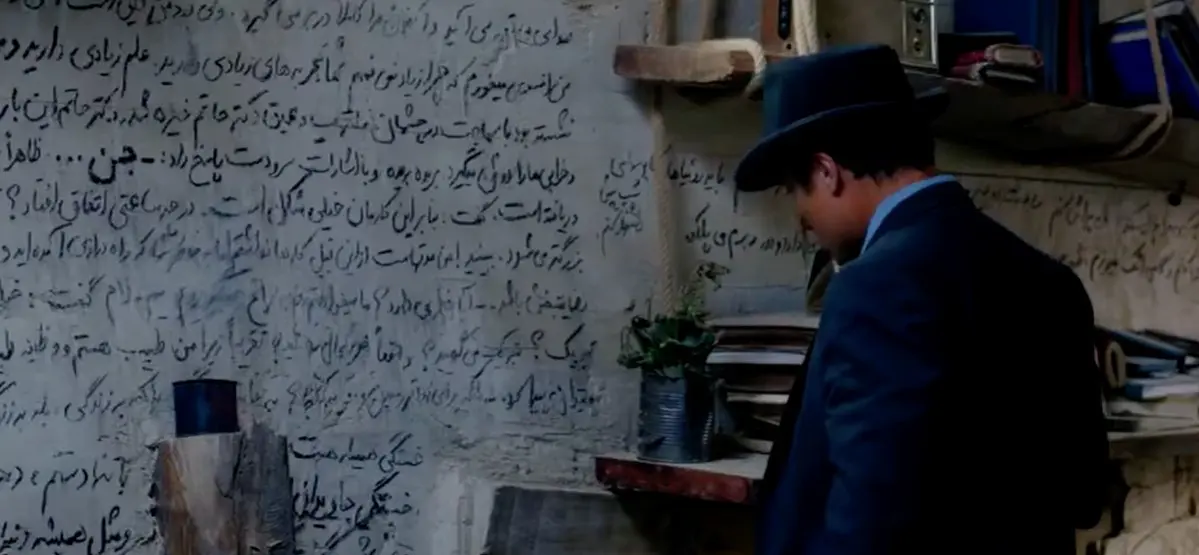

A Dragon Arrives! (2016)

Figure 1: Frame enlargement of the film poster for A Dragon Arrives! (Azhdahā Vārid Mīshavad, 2016), Mānī Haqīqī.

Introduction and Synopsis

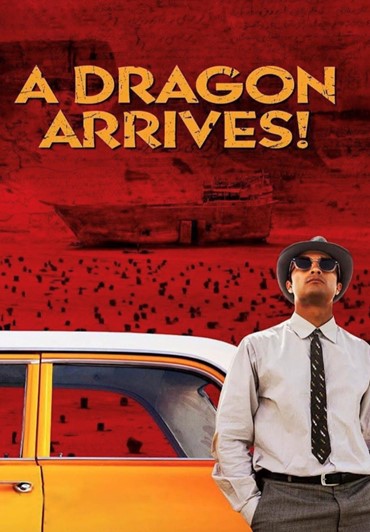

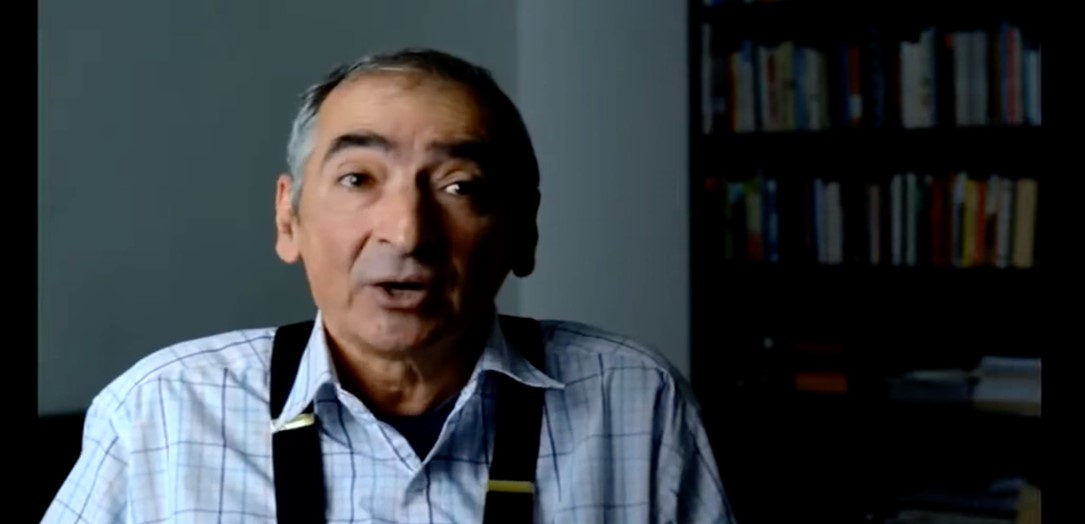

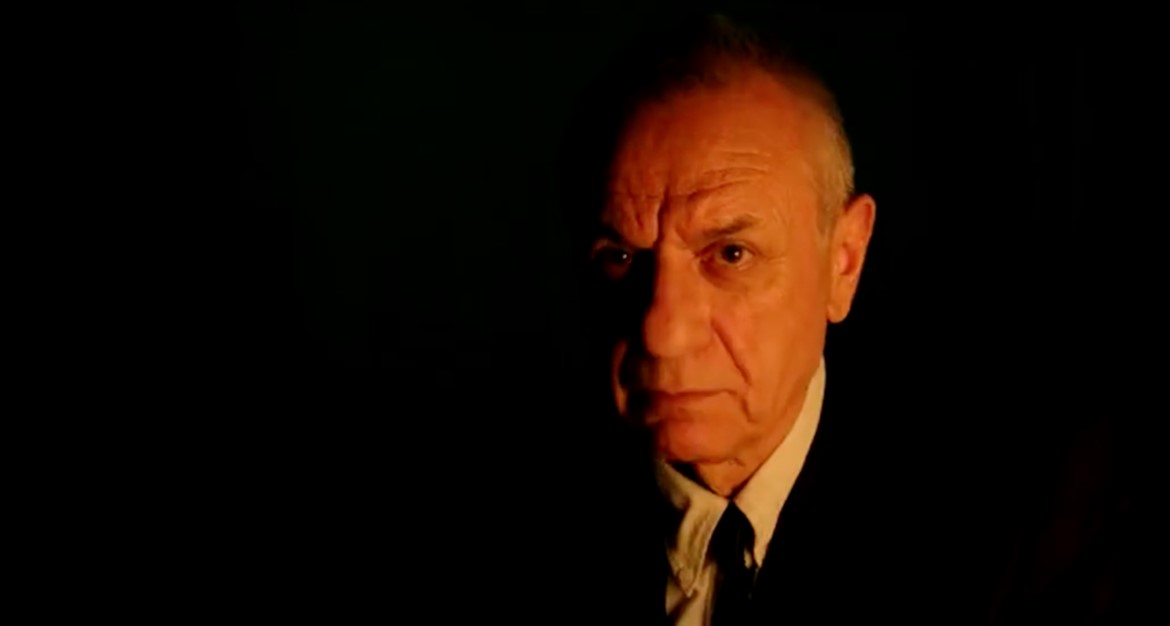

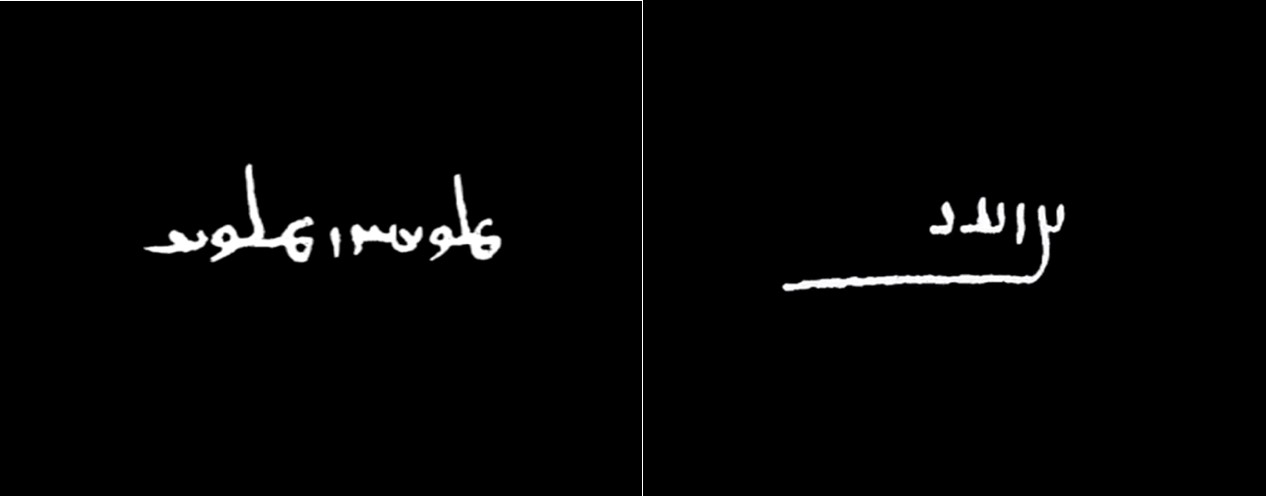

On Saturday, January 23, 1965, a SAVAK detective named Bābak Hāfizi (played by Amīr Jadīdī) is sent to Qishm, an island off southern Iran in the Persian Gulf, to investigate the suspicious suicide (or possible murder) of a Marxist-Leninist political exile at his resort, fashioned from the wrecked remains of a ship from an old war.1SAVAK is an abbreviation for Sāzmān-i Ittilā‛āt va Amnīyyat-i Kishvar, that is, “Intelligence and Security Organization of the Country.” Another SAVAK agent, Mr. Chārakī, is already on Qishm to assist Hāfizī with his investigations. The locals believe that the ancient cemetery known as Darrah-i sitārihā (the Valley of Stars) is haunted by a strange animal with black scales, and earthquakes strike any time a new body is buried there.Meanwhile, sporadically throughout the film, there are (staged) interviews featuring prominent figures in Iranian arts, politics, and the director Mānī Haqīqī himself. For example, Haqīqī at one point discusses a chest recently found in his family’s basement that inspired the making of the film. These interviews address several key concepts, including the significance of Huzvārish (هزوارش) in the Pahlavi language.2Dehkhoda’s online Farsi Dictionary defines Huzvārish as a verb which means to “explain, interpret and analyze.” See: “هزوارش,” Dehkhoda, accessed June, 4, 2023, https://www.vajehyab.com/dehkhoda/هزوارش. In another of the staged interviews, Sādiq Zībākalām, the Iranian neo-liberal reformist and academician, reveals that, “it was hard to believe that someone named Sa‛īd Jahāngīrī succeeded in infiltrating the SAVAK system—only God knows how—and he was able to take four-to-five other people to the department at which he worked and they made a group named Huzvārish” (see Figure 3).3A Dragon Arrives! 00:18:59 (All translations are by the author unless otherwise stated). In a real-life interview, Sādiq Zībākalām states that he simply repeated “like a robot” what Haqīqī asked him to say. During this interview, Zībākalām sheds light on his decision to participate in the film, despite his limited knowledge of Haqīqī. The primary reason behind his acceptance was the fact that the interview was initially intended to be with the renowned Iranian journalist, Mas‛ūd Bihnūd. However, due to the strict regulations imposed by the Islamic government, the film would not have obtained the necessary release permission had Bihnūd’s interview been included. Out of deep respect for Bihnūd and Sa‛īd Hajjārīyān, another influential reformist political activist and journalist, Zībākalām willingly stepped in as a substitute and “repeated like a robot what Haqīqī asked him to say.” See: “Sādiq Zībākalām chitur bāzīgar shud? Ravāyat-i Sādiq az ḥuzūr dar Azhdahā vārid mīshavad!” Aparat, September 15, 2018, accessed July, 6, 2023, https://www.aparat.com/v/KnRXz (00:06:40) However, to make it more complicated, in another staged interview, the Iranian historian Touraj Daryaee argues that “Huzvārish comes from Aramaic words that are inscribed in Pahlavi.”4A Dragon Arrives! 00:19:42. Additionally, a group of students in the film take on the task of investigating the mysterious death of the sound engineer from Ibrāhīm Gulistān’s film Khisht u Āyinah (The Brick and the Mirror, 1965) by conducting interviews (see Figure 2). Their efforts further complicate the film’s narrative, adding layers of intricate relational meanings.5During the Fajr Festival press conference, Haqīqī vehemently dismissed the notion of relying on symbolism, a characteristic often associated with his previous works. He expressed his disdain for fixed symbolism, instead favoring a dynamic approach to meaning-making:

To me, it’s about crafting an ambiance that suggests hidden depths, which I find incredibly alluring. However, I don’t expect the audience to uncover specific predetermined meanings that I’ve embedded in the film. I want them to embark on their own exploration. This interplay of meaning is an enthralling game in which we can all partake . . . I hope my films would create a system of meaning-making in which the audience can participate.

See: “Nishast-i khabarī-i Azhdahā vārid mīshavad bā ḥuzūr-i Mānī Haqīqī,” Aparat, February 9, 2016, accessed August 28, 2023, https://www.aparat.com/v/RQhKB (translated by the author).

Figure 2: The group of students/researchers interviewing different figures including Haqīqī himself on the making of the film and the story behind it. A Dragon Arrives! (2016), Mānī Haqīqī. Accessed June 6, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2hGuvh2Du-I (01:27:01)

Two friends, a photographer and geologist named Bihnām Shukūhī (played by Humāyūn Ghanīzādah) and Kayvān Haddād, a sound recorder preoccupied with recording the silence in Qishm (played by Ihsān Gūdarzī), accompany Hāfizī to document the investigation of the sketchy suicide (or murder) of the political prisoner and the other mysteries of the island. Throughout the movie, Hāfizī encounters some strange characters, including the shark hunter’s wife who initiates the detective into the healing trance-like ritual of zār (a term with multiple meanings such as “affliction” and “visitation” which I later discuss at length). After the zār ritual, the three friends make a shocking discovery: the dead, exiled Marxist got Halīmah, the shark hunter’s daughter, pregnant. Additionally, they uncover a conspiracy, concocted by the two other SAVAK detectives, Mr. Chāraki and Sa‛īd Jahāngīrī, that Halīmah’s father planned to kill both his daughter and the Marxist and stage it as a suicide.

The sound recorder and photographer-geologist eventually come across the pregnant Halīmah, located in the mortuary of the ship left from an old war. Halīmah dies during childbirth, but the two friends manage to save the baby. One of the other SAVAK agents, Jahāngīrī, investigates the three friends about what they have explored and found out regarding the mysterious death of the political exile. Due to what the three friends have discovered, the SAVAK agency chooses to halt the investigation and orders the execution of the three friends, including Hāfizī. During their attempt to escape the island, Hāfizī is killed, Haddād flees holding Halīmah’s child, and Shukūhī’s face is seen sinking into the water at night.

Figure 3: Sādiq Zībkalam explaining to the interviewers the political implication of Huzvārish as a group that Jahāngīrī shaped infiltrating SAVAK. A Dragon Arrives! (2016), Mānī Haqīqī. Accessed June 6, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2hGuvh2Du-I (00:19:02)

Throughout the movie, director Mānī Haqīqī weaves together themes of conspiracy, betrayal, and supernatural belief by incorporating elements of superstition, a fake documentary style, and Iranian history. As the director himself has admitted: “I wanted to prove, observe and test that the more I lie with confidence and audacity, the more believable my lies become. My experiment yielded concerning results.”6“Azhdahā Vārid Mīshavad,” Tiwall, March 3, 2016, accessed April 8, 2023, https://www.tiwall.com/p/ezhdeha.vared.mishavad (translated by the author).

Figure 4: Haqīqī in his own film, A Dragon Arrives!, explaining why he decided to make it. A Dragon Arrives! (2016), Mānī Haqīqī. Accessed June 6, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2hGuvh2Du-I (00:14:35)

Haqīqī’s statement about the increasing believability of his “lies” complicates his denial of any use of symbolic reference in his film. In fact, in press conferences, Haqīqī has heatedly denied any intentional use of symbolism in A Dragon Arrives!. Instead, he has expressed that his films “have never been symbolic or metaphorical,” and that he detests the use of symbols in his works.7“Nishast-i khabarī-i Azhdahā vārid mīshavad bā ḥuzūr-i Mānī Haqīqī,” Aparat, February 9, 2016, accessed August 28, 2023, https://www.aparat.com/v/RQhKB (00:05:20). However, despite Haqīqī’s aversion to symbolism, it is nearly impossible to disregard the symbolism inherent in A Dragon Arrives!, with the “dragon” being the most evident. Along these same lines, this article refers to Fredric Jameson’s conceptualization of the “political unconscious” to support the argument that the dragon’s “arrival” is in fact a politically symbolic one.

Through the combination of investigations of a suicide or possible murder, staged interviews, unravelling conspiracies, betrayals, and the dire fates of the three friends, alongside Haqīqī’s experiment of lies and his denial of symbolism, we are dealing with an extremely playful movie—most especially in the sense that Haqīqī seems to have used cinema to create a generative plane of interpretations. In the same manner, in a playful interpretation of A Dragon Arrives!, this article also borrows from the Pahlavi term Huzvārish, referenced in the film, which means to interpret, explain, and analyze.

In addition to exploring the symbolic aspects of A Dragon Arrives! —particularly its relevance as a symbol of the “arrival” of a new form of political resistance—this article emphasizes the importance of archival elements in constructing alternative historical narratives or creating false beliefs. In addition, the film’s supernatural elements, such as jinn, the use of zār, psychedelics, talismanic magic, and the dragon itself, are also analyzed to offer various interpretations of the plot and its wider meaning for Iranian politics today. The use of philosophical concepts and cultural references is intended to provide an in-depth understanding of the film’s underlying themes and meanings. Through this approach, this article contributes to the academic discourse of cultural symbolism concerning this important Iranian alternative film.

Intertextuality and Fragmentation

A haunted cemetery on Qishm island, circa 1960-65,

An old war-wrecked ship hosting a Marxist-Leninist political exile,

The mysterious murder or suicide of said political exile,

A recently found chest in the basement of Haqīqī’s family home,

A nosy SAVAK detective (from the late Pahlavi’s Intelligence and Security Organization),

A buried chest at the mysterious cemetery, later passed on to the director Gulistān’s family,

The mystery of the missing daughter of a shark hunter/ophthalmologist,

A lurking crevasse-dwelling dragon,

An eccentric sound recorder obsessed with the silence of Qishm island,

A witty photographer/geologist,

Zār rituals,

A psychedelic trance,

References to the Portuguese, Arabs, and (South Asian) Indians,

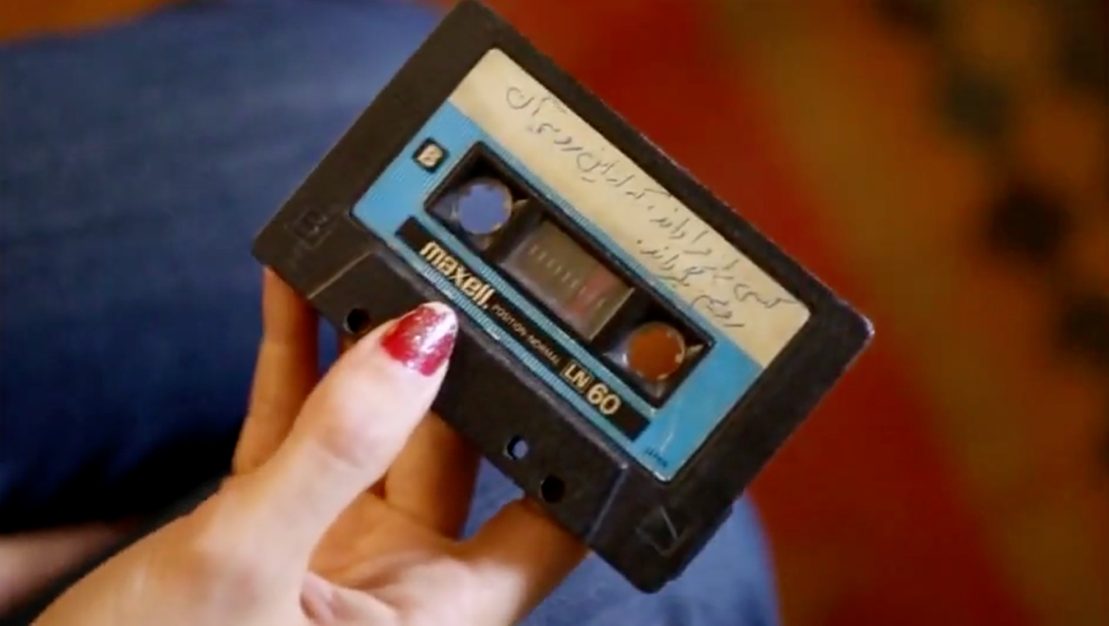

A Maxwell cassette tape marked by a fragment of a famous Iranian poet’s poem,

A camel with a broken leg,

A newborn,

Jinn,

A gun.

These are the ingredients of Mānī Haqīqī’s film A Dragon Arrives!. Add to them, among other things, a series of make-believe direct interviews with real people. On top of that, the opening credits acknowledge that A Dragon Arrives! is “based on a true story.”8A Dragon Arrives! 00:13:11. In subsequent interviews, Haqīqī and others confirm this claim, revealing that the film is inspired by a family chest recently found (see Figure 5), and the real-life disappearance of the sound engineer who worked on Haqīqī’s grandfather’s film, Khisht u Āyinah (The Brick and the Mirror, 1965) by Ibrāhīm Gulistān, a leading filmmaker of the Iranian New Wave.9The chest functions as a plot device (i.e., a “MacGuffin”) that pushes the story forward and makes it dramatically suspenseful (like the briefcase in Quentin Tarantino’s film, Pulp Fiction, from 1995). Among all these seemingly too-diverse elements, A Dragon Arrives! is, in actuality, a powerfully political and critical work that draws on a range of cinematic genres and intertextual references which explores Iran’s complex historical, cultural, and current political context. Apart from whatever interpretations one adopts, A Dragon Arrives! looks and sounds like an unsettled yet very enjoyable cinematic work.

Figure 5: The chest in the wrecked ship found by Shukūhī and later found in Haqīqī’s basement which inspired him to make the film. A Dragon Arrives! (2016), Mānī Haqīqī. Accessed June 6, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2hGuvh2Du-I (01:17:46)

Given its multiple textures and influences, Haqīqī’s film presents a complex and multifaceted narrative that invites multiple interpretations and readings, from the extremely symbolic to those dependent on film theories.10The film scholar and critic Farshid Kazemi considers A Dragon Arrives! as an example of the new wave of horror films in Iranian cinema, which is already nascent. For a thorough discussion of the new horror cinema in Iran, see: Farshid Kazemi, “Iranian Horror Cinema,” in Cinema Iranica Online, accessed April 25, 2023, https://cinema.iranicaonline.org/article/iranian-horror-cinema/ The thematic references of conspiracy and a climate of fear add depth and complexity to the film, as evidenced by the influence of Gulistān’s Khisht u Āyinah (The Brick and the Mirror) and the direct references to Bahrām Sādiqī’s novella Malakūt (The Heavenly Kingdom, 1961). By weaving together different perspectives and narratives, the film creates a fragmented sense of time that reflects how history is constructed and interpreted through the adoption of certain events by whoever controls the narrative. For instance, The Brick and the Mirror was produced during a time of significant modernization in Iranian society. Despite the expectations for this hoped-for, extensive modernization, the potential for democratic change had not yet been fully realized due to the second Pahlavi era’s oppressive regime of sovereign power (1941-1979). This gave rise to an atmosphere of paranoia and fear that is well reflected in Haqīqī’s film (set, as it is, in pre-revolutionary Iran). According to some cultural theorists such as Murtizā Āvīnī and ‛Abdulkarīm Surūsh, a return to Iran’s Islamic history, with more democratic interpretations, could provide an alternative vision after the 1979 revolution.11Murtizā Āvīnī (1947-1993) was an Iranian filmmaker, director, and war correspondent born in Tehran, Iran. Āvīnī is known for his documentary films and his coverage of the Iran-Iraq War in a documentary series titled Ravāyat-i fath (The Chronicles of Victory, 1980s). In Ravāyat-i fath, Āvīnī documented several important parts of the war and the spiritual atmosphere of sacrifice among the war’s participants. Āvīnī’s own intimate, affective, and genuine voice-over for the documentary gave it a lyrical and aesthetic dimension that enlivened the celebration of holy sacrifice/martyrdom and esoteric dimensions of the war. Four years after the end of the Iran-Iraq War, in an attempt to make a documentary about the martyrs of the conflict, Āvīnī himself was martyred (as he was on duty) when he stepped on an unnoticed live landmine while returning from a film shoot. Āvīnī’s documentation of the Iran-Iraq conflict has left a lasting impact on the collective memory of the war.

‛Abdulkarīm Surūsh (b. 1945 in Tehran) is an Iranian philosopher, theologian, and reformist thinker known for his critical and progressive views on Islam, religious interpretation, and the relationship between religion and modernity. He became a prominent figure in the intellectual and cultural debates in Iran during the 1980s and 1990s. Surūsh’s ideas revolve around the concept of rushanfikrī-i dīnī (religious intellectualism) which has been a kind of religious reformation. He argues for a reinterpretation of Islamic teachings in light of modern knowledge and values. Surūsh believes that religious knowledge should be dynamic and adaptable to the changing circumstances of society. His ideas have been influential in shaping the discourse on Islam and modernity in Iran. However, his views have also faced criticism and opposition from both conservative religious authorities and modern democratic thinkers. They believed that the modernization process had caused a drastic disruption in the traditional Iranian psyche, ultimately leading to an identity crisis that culminated in the revolution. Among other things, A Dragon Arrives! offers some insights into that fractured psyche.

In A Dragon Arrives!, Haqīqī employs a diverse array of cinematic genres, such as avant-garde, Acid Western, horror, mockumentary, direct interview, and detective mystery to create a postmodern work that defies easy classification.12Acid Western is a subgenre of the Western film genre that emerged in the 1960s and 1970s. It is characterized by its unconventional and often psychedelic style, as well as its exploration of darker themes and countercultural ideas. The term “acid” in Acid Western refers to the psychedelic drug culture popular during the 1960s and reflects the genre’s use of hallucinatory imagery and themes. Acid Westerns are sometimes referred to as “Neo-Westerns” or “Post-Westerns,” as they deviate from the traditional Western formula and address contemporary social and political issues. The genre also frequently incorporates elements of mysticism and surrealism, such as dream sequences and hallucinations. Some notable examples of Acid Westerns include films like Monte Hellman’s The Shooting (1966), Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider (1969), Alejandro Jodorowsky’s El Topo (1970), and Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man (1995). In addition, by displaying the performativity of filmmaking with documentary interview scenes, A Dragon Arrives! challenges the authenticity of realism. Notably, while Haqīqī’s use of fake documentaries is unconventional, the technique itself is not new. For instance, Woody Allen’s Zelig (1983) is a well-known example of a heterogeneous film that employs fabricated documentary footage, staged performances, and fictional elements to construct a bizarre and sometimes absurd storyline.13Haqīqī’s interest in absurdism can be seen in some of his previous works such as Kārgarān mashghūl-i Kārand, (Men at Work, 2006) and Pazīrā’ī-i sādah, (Modest Reception, 2012).

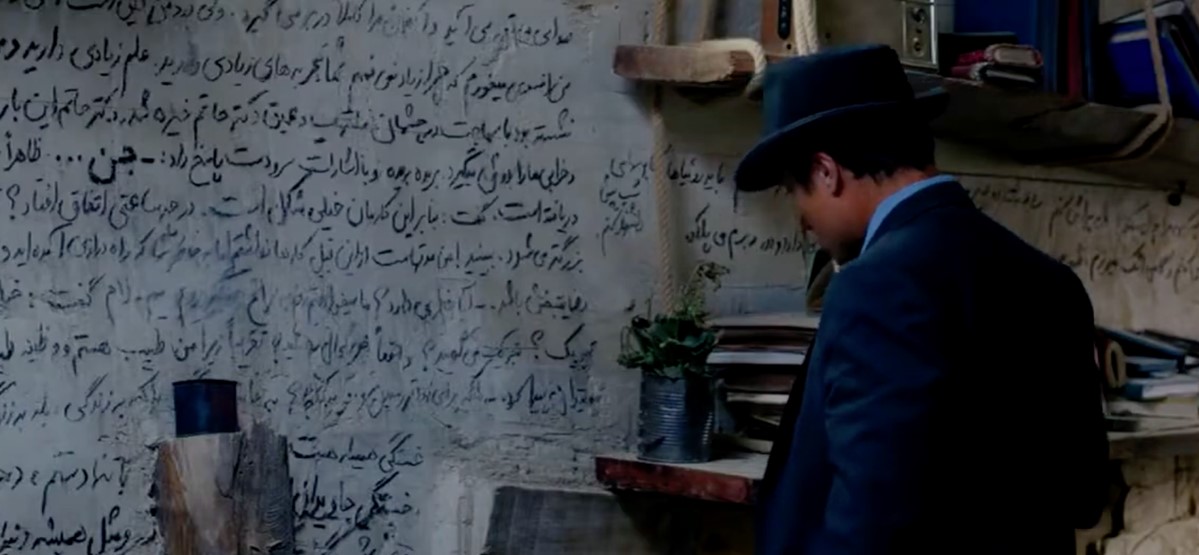

Further, the intertextual references to other works and their interplay with the theme and structure of the film are of paramount importance to its interpretation.14For example, the film’s engagement with the theme of jinn and allegory allude to The Secrets of the Treasure of the Jinn Valley (1974, original Farsi title: Asrār-i Ganj-i Darrah-yi Jinnī) by Ibrāhīm Gulistān. Gulistān’s film satirically criticizes the superficial modernization of the Second Pahlavi era by exploring the discovery of a hidden treasure on a peasant’s property, transforming the peasant’s lifestyle from impoverished to affluent. Drawing inspiration from Bahrām Sādiqī’s novella Malakut (The Heavenly Kingdom) and incorporating archival elements, the film transcends its medium and becomes literature itself, haunted by Mr. Mavaddat’s wall-written diaries. This is apparent from nearly the very beginning of the film when the voiceover reads the first line of Sādiqī’s novella: “At eleven o’clock on Wednesday night of that week, the jinn settled in Mr. Mavaddat.”15A Dragon Arrives! 00:11:45.

Figure 6: The diaries of political exile written on the ship’s wall. A Dragon Arrives! (2016), Mānī Haqīqī. Accessed June 6, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2hGuvh2Du-I (00:10:33)

Furthermore, the Marxist-Leninist exile’s handwritten diaries and graphic calligraphy on the wall of his strange residence—a ship sunken in the desert—offers a representation of practically living amongst the pages of his own version of the story of Malakut (see Figure 6). Additionally, the theatre performance of ‛Abbās Na‛lbandīyān’s play, A Deep and New Research on the 25th Geological Period of Rocks, or the 14th, 20th Etc. … It doesn’t matter in the film, and the performance-like quality of almost all the shots, add to the intermediality—the intermixing of literature, film, theatre, and performance—of the film.16The full title of the book is: Pazhūhishī zharf va siturg va naw, dar sangvārāh-hā-yi dawrah-yi bīst u panjum-i zamīn-shināsī yā chahārdahum, bīstum, va ghayrah, farqī nimīkunad (A Deep and New Research on the 25th Geological Period of Rocks, or the 14th, 20th Etc. … It doesn’t matter).

In addition to the use of archival elements, the Southern locals’ peculiar customs, superstitions, and beliefs are also intertwined with the detective mystery, both compelling the viewer’s interest until the end and contextualizing the film’s themes within the country’s social and historical context. Since “film’s historical context is essential in interpreting its meaning,” the political intelligence-induced mysteries and the specificity of supernatural elements such as zār and jinn in Qishm are also worth considering (which I turn to later in detail).17Robert C. Allen, Film History: Theory and Practice (Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1985), 11.

The film’s address to the archives (i.e., that the film is drawn from “real life” and events) also challenges how alternative interpretations can inspire and shape Iran’s history, politics, and religion. By using constructed reality and staged interviews, the film makes the audience assume that they are watching a re-enactment of a true story, while the story is in fact a mixture of staged interviews and fiction. In this way, Haqīqī invites audiences to engage more deeply with the film’s themes and raises essential questions about the authenticity of historical facts and the relationship between archives, history, and storytelling. Accordingly, the film addresses the contradictions and complexities of Iran’s political history.

Furthermore, the film explores the importance of personal archives as possibilities for making alternative histories that challenge how a nation’s history, politics, and religion can be constructed. Relatedly, the film’s use of metafiction, such as the director Haqīqī’s and other interviewees’ voiceovers, adds a unique feature that plays on the true vs. the false. Haqīqī shows how false beliefs can be created through the manipulation of media, particularly cinema, and how the exploration of superstition can be a commentary on the manipulation of religiosity, associated with current practices of the supernatural, such as jinn exorcism and psychic fortune-telling (rammālī), which have become more prominent among some real-life Iranian politicians (Mahmūd Ahmadīnizhād seems to be one of the pioneers).18After the election of Mahmūd Ahmadīnizhād as the Iranian president (2005-2012), superstitions and the practice of superstitious fortune-telling through jinn have become dominant among some politicians in Iran. For example, as Abbas Amanat discusses (2017; see the end of this footnote), Ahmadīnizhād also “used to lay an extra place for the 12th Imam at his weekly cabinet briefings.”

In addition to this veritable cornucopia of intertextual influences, Haqīqī’s use of fragmentation is equally important. As Lotte Meinert and Bruce Kapferer argue, fragmented narrative often mirrors the realities of fragmented social, political, and economic processes and can be used as a means of criticizing those processes. As such, fragmentation can be seen as a mode of addressing contingency and the fragility of politics and social structures.19Lotte Meinert and Bruce Kapferer, In the Event: Toward an Anthropology of Generic Moments (Berghahn Books, 2015), 7. This technique is a common feature of postmodernist and experimental films and is used in A Dragon Arrives! to subvert traditional cinematic conventions, destabilize established forms of meaning-making, and prompt viewers to engage actively with the film’s enigmatic narrative. Specifically, the Iranian audience is already familiar with fragmented and labyrinthine storytelling styles, particularly through the Islamicate Rite of Passion Plays (ta‛zīyah). A performance tradition dating back fourteen hundred years, ta‛zīyah involves the portrayal of the tragic killing of religious figures through dramatic re-enactments. These performances were believed to be true by the Ramadan mourners, who participated in the yearly ceremonials of the martyrdom of Imam Husayn, due to deeply ingrained prejudices and the promotion of a sense of sacredness surrounding the martyrs in Shi’a history, creating a powerful and immersive experience for the audience.

To explore the film’s influences even deeper, it is important to acknowledge how A Dragon Arrives! also follows a complicated pattern reminiscent of the intricate and intertwined lines of narrative found in One Thousand and One Nights, Persian/Arabic classical literature, animal fables such as Kalīla va Dimna, and the books of the mystic poet Jalāl al-Dīn Muhammad Rūmī (popularly known as Rumi, 120781273), such as Fīhi Mā Fīh (1316, loosely translated as In It What Is In It) and Mas̲navī maʻnavī (1441).20One Thousand and One Nights, with the original Arabic title Alf Laylah va-Laylah, also commonly known as The Arabian Nights from the first English-language edition (c. 1706–1721, which was translated originally as The Arabian Nights’ Entertainment), is a collection of Middle Eastern folk tales and stories with an uncertain year of publication due to the collection’s complex history. Originating in the Islamic Golden Age, the stories have been continuously revised and added to over many centuries. The most famous Arabic manuscript, the Cairo edition, dates back to the fourteenth-century CE and includes well-known stories such as “Aladdin’s Wonderful Lamp” and “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves.” For a more recent version of the English translation, see: J. C. Mardrus and E. P. Mathers, The Book of the Thousand and One Nights (Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2013).

Kalīla va Dimna (or Kalila and Dimna, also known as The Fables of Bidpai), is an ancient collection of animal fables with roots in Indian and Persian literature. It has been translated and adapted into various languages over the centuries. The original version is believed to have been written in Sanskrit (titled “The Panchatantra”) Its exact year of publication is not well-documented; however, the surviving work is dated to about 200 BCE or perhaps even as early as the third century BCE. The most well-known Arabic translation of Kalīla va Dimna was written by Ibn al-Muqaffaʿ (d. circa 760 BCE) a Persian scholar, in the eighth-century CE. This translation played a significant role in spreading these stories throughout the Islamic world and is considered one of the earliest and most influential renditions of the work. It’s important to note that Kalīla va Dimna has been passed down through oral and written traditions and various versions and adaptations exist. The specific year of publication may not be available, given the ancient origins and the numerous translations and retellings of the fables over time. For an example of an Arabic manuscript version attributed to Ibn al-Muqaffaʿ with illustrated miniatures published in fourteenth-century Egypt, see: Ibn al-Muqaffaʿ, trans. Kalila and Dimna (Egypt: circa. 1310), retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/item/2021667224/.

Regarding Rūmī’s works, see: Bankey Behari, Fiha Ma Fiha, Table Talk of Maulani Rumi (DK Publishers, New Delhi, 1998); and Jalāl Al-Dīn Rūmī, Mas̲navī-i maʻnavī, Volume 3 (Tehran: Amīr Kabīr Publication, 1984).

This complex narrative pattern creates a maze-like structure that has the potential to captivate and astonish the audience, particularly when executed with deliberate intention, similar to the works of renowned storyteller Jorge Luis Borges and his labyrinthine narratives. In this style of storytelling, the blending of—indeed, the lack of any difference between—fact and fiction becomes a technical aspect, where fabricated tales are presented as if they were genuine accounts. This deliberate erasing of the border between ideas of reality and lies adds to the complexity and richness of the narrative, asking for more active engagement of the audience with the film narrative, demanding them to answer: what are the boundaries between reality and imagination?

On the other hand, A Dragon Arrives! can be compared also to more contemporary manifestations of fragmentation in film, such as Christopher Nolan’s Memento (2000), particularly in comparison to Nolan’s use of non-linear narrative and fragmented imagery. Thus, fragmentation can create a sense of uncertainty and disorientation by disrupting the viewer’s sense of chronology and causality. As a result, the fragmented narrative of A Dragon Arrives! challenges established norms and power structures, leading to a deeper engagement with the film’s theme of mystery. While I will return to these elements later, the use of psychedelics, superstition, and mystery in A Dragon Arrives! also operate to transcend realism, allowing the film to enter the realms of magic and surrealism. This occurs, for instance, when Halīmah’s mother, the shark hunter’s wife, offers Hāfizī a psychedelic cigarette, telling him to “smoke it; you won’t understand what I’m saying until you smoke it” (see Figure 7).21A Dragon Arrives! 00:47:17.

Figure 7: Halīmah’s mother offers Hāfizī the psychedelic cigarette. A Dragon Arrives! (2016), Mānī Haqīqī. Accessed June 6, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2hGuvh2Du-I (00:47:17)

After smoking the cigarette, Hāfizī and his two friends experience a psychedelic phase that introduces them to an exploration of the island’s enigmas, eventually uncovering the SAVAK agency’s secrets. The psychedelic trance references traditional rituals such as zār that alter consciousness, ironically disrupting traditional modes of perception and allowing for a further exploration of different states of consciousness.22Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari suggest that such drug-induced trances can cause gaseous consciousness, which leads to what they conceptualized as a “body without organs” in their book Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (1972). A “body without organs,” they argue, is a state of pure potentiality and openness to experience. The concept of “body without organs” is introduced in Chapter 3 of Anti-Oedipus in the section titled “A Materialist Psychiatry.” Deleuze and Guattari describe the “body without organs” as a “full body” that is not yet “formed” or “organized” by the dominant structures of society, such as language, law, and ideology. They argue that the dominant structures of society impose “desiring-production,” or how desires and social relations are produced and regulated upon the body. This process leads to the formation of a “body with organs” defined by its functions and roles in relation to the dominant structures of society. In contrast to the “desiring-production,” the “body without organs” represents a state of pure potentiality, where desire is free from the constraints of social norms and is free to experiment and create alternative forms of existence and social relations. See: Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, “A Materialist Psychiatry,” in Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Robert Hurley et al. (University of Minnesota Press, 1983): 149–155. Haqīqī’s use of psychedelia and zār music makes A Dragon Arrives! a psychedelic film in which symbols and signs conjure new meanings and interpretations of reality from a more expanded perception of reality. By doing so, A Dragon Arrives! is like other “[p]sychedelic films [which] challenge the linear, left-brain dominance that structures our waking lives and offer us an opportunity to step into the right-brain world of metaphor, symbol, and vision. They reveal the underlying structures of reality, transforming the mundane into the fantastic and the invisible into the visible.”23Jeffery Zacks, Flicker: Your Brain on Movies (Oxford University Press, 2014), 212.

On the other hand, fragmentation and surrealism encourage viewers to question the stability of their perceptions and identities, reflecting the characters’ psychological and subjective experiences. In this way, A Dragon Arrives! encourages audience participation in the film world without any presumptions that might block the magic of images and sounds, allowing them to explore the depth of the island’s psyche and its secrets. Meanwhile, the metafiction of the film disrupts our anticipation of a straightforward narrative and urges us to reflect on how meaning is formed within the film, prompting us to interact with the movie in an engaged and imaginative way.

Archives: Is History a Novel in Writing?Archives are the depositories of social memory, but they are also constructed out of the very same social processes that they record. They reflect the desires and biases of their creators, and their selective preservation of specific documents and artifacts shapes our understanding of the past. Archives are not neutral; they are always implicated in constructing reality.24Jaimie Baron, The Archive Effect: Found Footage and the Audiovisual Experience of History (Routledge, 2014), 8. History is not only a set of stories but also a set of styles of seeing and representing the world. In this sense, film, like literature, is not only a cultural artifact but also a representation of cultural processes and practices, a window into how history is remembered, constructed, and represented.25Richard Neupert, A History of the French New Wave Cinema (University of Wisconsin Press, 2007), 3.

One of the various techniques Haqīqī uses to create a fragmented narrative that mirrors Iranian society is the way in which he employs archival footage, photographs, and recorded voiceover narration in the film to convey a fake storyline from the very beginning. In her book Framer Framed (1992), the filmmaker and theorist Trinh T. Minh-ha discusses the use of archival materials as a means of challenging dominant narratives and constructing new forms of knowledge.26Trinh T. Minh-Ha, Framer Framed (Taylor & Francis Group, 1992). Minh-ha’s argument importantly demonstrates how archives shape our understanding of history and how this understanding can come back differently to haunt us. In this way, the film’s depiction of the investigation into the exile’s death on the island is a kind of archival project. As the characters sift through local superstitions and rituals to uncover the truth about what happened, they recover forgotten histories that were supposed to be out of reach as intelligence secrets. These elements foreground the role of archival investigation and extraction in constructing historical narratives.

Figure 8: Jahāngīrī, the assigned-to-Qishm SAVAK agent whose investigation of the three friends is occasionally displayed as they tell their stories of the incidents relating to the suicide (or the possible murder) of the Marxist exile. A Dragon Arrives! (2016), Mānī Haqīqī. Accessed June 6, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2hGuvh2Du-I (00:01:27)

In fact, A Dragon Arrives! begins with a direct archival element: the voice recorder that Jahāngīrī used to record his investigations of the three friends (see Figures 8 and 9). Haqīqī’s use of such archival materials is a way to challenge dominant narratives and create new forms of knowledge about Iranian history and politics. At the seventy-eight-minute mark of the film, for instance, Shahrzād Bishārat visits a pharmacy and covertly hands her fiancé—the sound recorder—a note that reads: “Everything is in Halīmah’s grave.”27A Dragon Arrives! 01:18:27. This cryptic message sets off a chain of events leading to the excavation of Halīmah’s grave—an act that can be interpreted as an archival investigation of the past to understand the present. Through these events, the film explores the relationship between memory and history and how archives can shape alternative histories that challenge dominant narratives by uncovering hidden truths that may have been silenced or buried.

Following the advice of this note, the group of friends discover a cache of secret documents that delineate a series of memories, interspersed with interviews, that are supposed to make the story believable. A remembrance of Gulistān’s film, which is performed by recalling the mysterious disappearance of the film’s sound engineer, emphasizes how memory is essential in constructing a sense of history, and that without memory such experiences would be lost. As Shoshana Zuboff writes:

Memory is the bridge between the private and the public domains of experience, between subjective awareness and collective history. Without memory, experience dissolves into the existential confusion of an eternal present. Without memory, history has no meaning, substance, direction, or purpose.28Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (Public Affairs Publication, 2019), 383.

Indeed, archival memory can be a powerful tool in uncovering hidden histories and secrets of society; however, in A Dragon Arrives!, the audience must contend with multiple narratives that contextualize each other. For instance, as audience members, we need to know the sociopolitical context of the production of Gulistān’s The Brick and the Mirror which in turn contextualizes the making of A Dragon Arrives!. Together, these two films operate as if they are two inseparable strata—especially through the presence of a parentless newborn that occurs in both films.

Figure 9: The film opens with the sound-recorder used by Jahāngīrī to record his investigations of the three friends. The recorder is displayed at different occasions in the film (e.g., at 01:10:21). A Dragon Arrives! (2016), Mānī Haqīqī. Accessed June 6, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2hGuvh2Du-I (00:00:25)

Figure 10: The Maxwell cassette tape with Mahdī Akhavān-Sālis’ poem, Katībah, which includes the lines, “That who knows my secret / That who flips my side,” written on one side. A Dragon Arrives! (2016), Mānī Haqīqī, Accessed June 6, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2hGuvh2Du-I (01:30:00)

Figure 11: The cassette player that plays the other side of the Maxwell cassette which contains Haddād’s voice talking about recording the dragon’s silence. A Dragon Arrives! (2016), Mānī Haqīqī. Accessed June 6, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2hGuvh2Du-I (01:39:34)

However, Haqīqī’s attempt to construct a cinematic truth through documentary is achieved only halfway because all the elements within the film are fabricated, including the details of a fictional historical incident. The film’s title itself is borrowed from the martial-arts movie Enter the Dragon (1973), further contributing to the postmodern pastiche elements of the film. Overall, the film performs the insight that history is a subjective representation of past events shaped by the intentions and perspectives of those in power who write and edit it.29In his book The Poverty of Historicism (1944), the philosopher of science Karl Popper challenges the notion of historicism, which posits that history unfolds according to predetermined laws and patterns, and contends that such a framework overlooks the role of human agency and subjectivity in shaping the past; however, the French philosopher Michel Foucault’s seminal book, The Archaeology of Knowledge (1972), argues that power and knowledge have significantly influenced the discourse around the production and utilization of history, and the concept of “discourse” has proved particularly influential in this regard. Similarly, Ifi Amadiume’s work, The Politics of Memory: Truth, Healing, and Social Justice (2008), explores how political elites employ their control over historical narratives to legitimize their power and to marginalize certain groups within society. See: Karl Popper, The Poverty of Historicism (Routledge, 1957); Michel Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge, trans. A. M. Sheridan Smith (Routledge, 1972); and Ifi Amadiume, The Politics of Memory: Truth, Healing, and Social Justice (Zed Books, 2008).

Thus, Haqīqī uses archival materials to create his own version of history, thereby challenging and ridiculing the authority and authenticity of natural historians (or politicians). He explores how effectively a wholly fabricated history can be constructed, highlighting how those in power fear alternative histories. The truth is often hidden behind a veil, and opposition to the dominant narrative is often deemed dangerous as it carries the potential to bring to the surface all the hidden power (i.e., the “dragon”) that can create significant change. This can be felt most keenly when Hāfizī discovers Halīmah, a minor character who has broken free from tradition and sought refuge in her love for the exiled prisoner. When he finds her she is giving birth to Vāllah, who emerges from the depths of the earth more than a little akin to a representation of the unconscious. In these same depths, another creature—the dragon—serves as a metaphor for latent power. The earthquakes it causes then are also a metaphor for change, a tremor limited to the boundaries where people are buried in the unconscious mire of historical and un/remembered fragmentation.

Another related instance in the film occurs while Haddād records the silence of Qishm’s sunset, his voiceover reflecting on the transformation of a strange creature that shifts from roaring to becoming breathless. He remarks,

Finally, I found it, in this crypt, in the middle of Tehran. At one point, it used to shake the cemetery with a jolt and would split the ground and pour out her guts. I witnessed it with my own eyes. Now, it doesn’t even shake. She even breathes in silence. She just looks, sometimes blinking slowly . . .30A Dragon Arrives! 01:28:15.

The voiceover then transitions to Haqīqī directly addressing the Maxwell cassette tape, one side of which bears a handwritten line from Mahdī Akhavān-Sālis’ poem Katībah (Inscription):

That who know my secret

That who flips my side.31A Dragon Arrives! 01:29:58. The line of poetry is from: Mahdī Akhavān Sālis, Az īn Avistā [From This Avesta], 5th ed. (Tehran: Murvārīd, 1981), 122.

Subsequently, Haqīqī flips the cassette and presses the play button, revealing the SAVAK agency’s recorded investigation of the sound recorder, and further describes the situation under investigation by Jahāngīrī, another SAVAK agent. The reference to the cassette with a line from Akhavān-Sālis’ poem makes the film more enigmatic by increasing intermediality and, as a result, the interpretability of the work (see Figures 10 and 11).

Finally, Haqīqī’s depiction of a camel with a broken leg which should be put down can be interpreted as a commentary on an old, stagnant heritage that requires termination and rejuvenation—a transition where the new supersedes the old.32A Dragon Arrives! 00:49:06. While not as enigmatic or powerful, perhaps, as Haddād’s recorded silence of the island (and the dragon), the lame camel as a message of opposition against the dominant yet tired and indeed crippled state of things is no less clear.

In combination, Haqīqī’s storytelling through intertextuatlity, fragmented narrative, and archival elements in A Dragon Arrives! transports the audience into a realm of enchantment and mysticism. No less so than by the added inclusion of talismanic objects discovered within a hidden chest and the references to zār and the Azhdahā (dragon) which infuse the story with a touch of magic and the supernatural.

The Talismanic and the Magical

For a film as indebted to the supernatural, magical, and mythological as A Dragon Arrives!, it is worth considering briefly some of the ways in which talismans, belief, and even dreams continue to hold influence, most especially in relation to film. For instance, Laura U. Marks, the Canadian media and cultural studies theorist, explores the history and practice of talismanic magic in both Islamic and European cultures, arguing that the roots of talismanic magic can be traced back to the Islamic Neoplatonist tradition of Yaqūb ibn Ishāq al-Kindī.33Laura U. Marks, “Talisman-Images,” The Nordic Journal of Aesthetics 61-62 (2021): 134-139.

As Marks explains, the practice of talismanic magic has a long and rich history in both Islamicate and European cultures. According to al-Kindī’s theory of causation in De Radiis, the stars and planets emit rays that affect everything in the sublunar world, and each affected thing also sends out rays that affect other things. This cosmology, based on the concept of emanation, holds that all creation emanates from a unitary entity, allowing for a link between every heavenly and sublunar entity. Talismans thus function as conduits between the material and spiritual realms, enabling the magician to manipulate energies that might otherwise be beyond human control.34Marks, “Talisman-Images,” 134-135. Marks further emphasizes the role of visual talismans in working transformations in the world, demonstrating the continued relevance of talismanic magic today by noting that, “[i]n our time, certain artworks, performances, and movies . . . act as talismans by developing connections between earthly bodies and cosmic forces.”35Marks, “Talisman-Images,” 136-138.

Relatedly, in his seminal book, The Interpretation of Dreams (1899), the famous Austrian psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud argued that the origin of magic lies in primitive humans’ attempts to understand and control the world around them. Freud believed that a “magical technique” is rooted in “the over-estimation of the psychic factor.”36Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams (Hogarth Press, 1900), 535. According to Freud, humans developed an animistic system of belief in which external events were believed to be influenced by human desires and wishes, leading to the development of religions, sacred or ritualistic protocols, and magic. This system formed the basis for the belief in the power of thought and the practice of such magical techniques.37For more on this topic, see: Laura U. Marks, “Talismanic Materiality: From Ancient Times to the Digital Age,” Journal of Material Culture 18, no. 2 (2013): 113-131; Maslama al-Qurtubi, Picatrix: A Medieval Treatise on Astral Magic, trans. by Dan Attrell and David Porreca (Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2019); and Emilie Savage-Smith, ed., Magic and Divination in Early Islam, (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2021). Further, and bringing these ideas into increased illumination and importance, we may argue that in movies, magic might be associated with marginalized groups and individuals who have been excluded from mainstream society. By asserting their agency through magic, these characters can challenge the dominant order and offer fresh perspectives on what is possible.

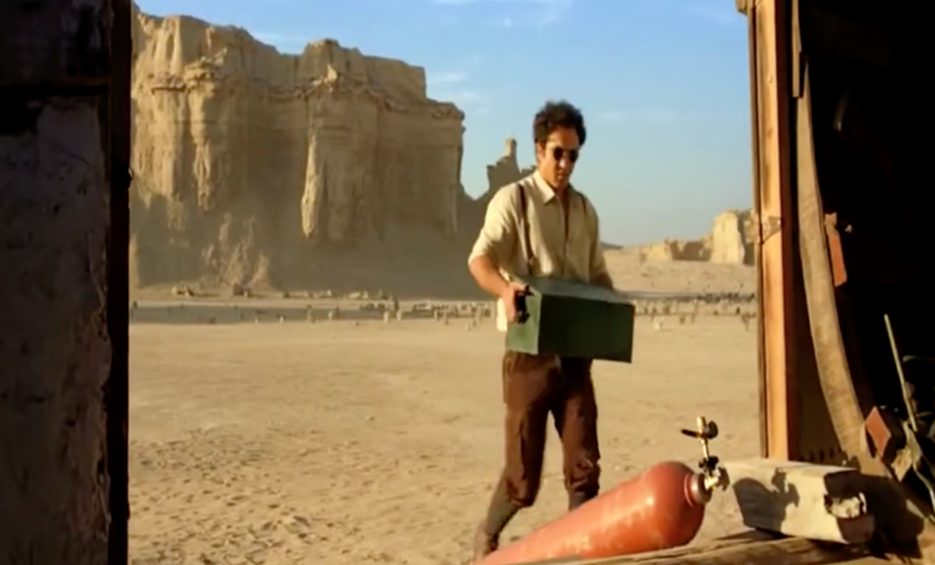

Thus, as a complex, visual work, A Dragon Arrives! can be interpreted as a talismanic object itself, composed of heterogeneous elements including the presence in the film of two archival chests—one of which contains talismanic objects (see Figures 12, 13 and 14). The first chest includes a collection of objects which are associated with magical essence, including an astrolabe, metal talismans, charms, a fragment of an animal’s bone, an old book, a pen case, and a knife. These objects resist straightforward interpretation and require thorough investigation to uncover their full significance. Despite the impracticability of comprehending their full significance, the film offers a thought-provoking exploration of the power of talismans and their ability to evoke a sense of mystery and fascination. In this way, the film operates like a talisman full of talismans.

Figure 12: A chest that Shukūhī found in the wrecked ship. A Dragon Arrives! (2016), Mānī Haqīqī. Accessed June 6, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2hGuvh2Du-I (01:17:54)

Figure 13: Haddād taking the chest he found buried in the cemetery. A Dragon Arrives! (2016), Mānī Haqīqī. Accessed June 6, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2hGuvh2Du-I (01:19:31)

Figure 14: The chest full of balloons that Shukūhī releases into the sky for taking photographs. A Dragon Arrives! (2016), Mānī Haqīqī. Accessed June 6, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2hGuvh2Du-I (00:34:22).

There are many such talismans in the film, including poetry. For instance, Mikhail Bakhtin, the Russian literary critic and theorist, believed that “The poetic image is itself a kind of talismanic device, a miniature representation of the world that brings into its confines the riches and complexities of the universe. The poetic image can be seen as a kind of verbal amulet, capable of exercising a magical influence on the reader.”38Mikhail Bakhtin, Speech Genres and Other Late Essays, ed. Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist, trans. by Vern W. McGee (University of Texas Press, 1986), 122. In this way, poetry itself can be considered an art form that transforms language into a talismanic object, imbuing it with a sense of magical potency and giving shape and significance to the often-disordered events and experiences of life. Poetry, therefore, serves as a talismanic magic that helps individuals derive meaning from the chaos surrounding them.

Importantly, the key talisman in Haqīqī’s film is a fragment (mentioned earlier) of Akhavān-Sālis’ poem (katībah, “Inscription”) found on an old Maxwell tape. This particular talisman conceptualizes the film’s vague, mysterious theme by unfolding it in the form of a fragment of a poem:

Kasī rāz-i ma-rā dānad,

Ki az īn rū bi ān rūyam bigardānad.

That who knows my secret

That who flips my side.39Akhavān Sālis, Az īn Avistā [From This Avesta], 122.

Mainly, this poetic fragment conceptualizes a border between now and then, an invitation to transform, a call to fight with so-called eternity and create a new fortune by meeting its conditions: that is, to know the “secret” by flipping the tape which is made up of a description of silence!

Figure 15: The chest found by Haddād under the cemetery with talismanic objects. A Dragon Arrives! (2016), Mānī Haqīqī. Accessed June 6, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2hGuvh2Du- (00:34:10)

The second chest in A Dragon Arrives! contains more recently found archival photographs, a physical copy of the book Malakūt, and a few reels of 16mm film and other sound recordings. These objects generate vague impressions, connections, and outcomes rooted in individuals’ objectives and yearnings. The film also features a third chest carried by Shukūhī which contains colorful balloons that he later releases into the air (see Figure 14). The interplay between these three chests complicates and even confuses the viewer’s perception of the film and its “McGuffin.” However, Hāyidah Safīyārī’s subtle film editing effectively renders them indistinguishable, adding to the enigmatic aura surrounding the multiple chests.

Figure 16 (left): The Pahlavi word malikān (meaning farmānravā, the ruler). A Dragon Arrives! (2016), Mānī Haqīqī. Accessed June 6, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2hGuvh2Du-I (00:20:11)Figure 17 (right): The Pahlavi word gabrā (meaning mard. man). A Dragon Arrives! (2016), Mānī Haqīqī. Accessed June 6, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2hGuvh2Du-I (00:20:14)

Regarding the brief reference to the Pahlavi word Huzvārish by the Iranian scholars Zībākalām, Hajjārīyān, and Daryaee in the film, it is possible to interpret Huzvārish as yet another symbolic word with unfamiliar calligraphy that carries talismanic potential.40A Dragon Arrives! 00:01:24, 00:19:46, and 00:19:49. The scholars are depicted in the film in quick succession. The word originally means “to interpret, explain and analyze,” which is relevant to the larger context of the film’s themes and its references to the supernatural.

The Supernatural: Zār, Jinn, and Azhdahā

When these themes of archival and intermedial influence are taken together, A Dragon Arrives! can be easily seen as an allegory of contemporary Iran. This allegory is clearly represented by the dragon, a symbol of Iran’s ancient power that is sleeping, waiting for awakening in the form of new capabilities, beliefs, and possibilities in Iranian culture and society—and especially political resistance. In other words, the dragon represents the oppressed power of the nation that will emerge from the very cracks caused by the religious superstitions that run through Iran’s history.

A central element of A Dragon Arrives! comes from the portrayal of mysterious events on Qishm island which draw upon the island’s folklore and culture and, in doing so, play upon belief in superstitions. Through depicting supernatural elements and superstitions such as jinn and zār, the film explores their potential power as both a source of threat and of healing. Specifically, the jinn and the ritual performance of zār serve as the two primary supernatural elements in the movie, reflecting the complex beliefs and relationships on the island with the “Other.” This includes the representation of a strange monster living at the heart of the earth and the foreign fatalities of an old war buried in the same cemetery. By utilizing these supernatural elements and superstitions, A Dragon Arrives! reveals an intricate interplay between the spiritual and the material world on the island. In particular, the film explores how these beliefs and practices can both frighten and provide comfort to individuals living within the community. Through its examination of these cultural and spiritual practices, the film offers a unique perspective on how communities navigate the boundaries between visible and invisible worlds.

Zār

Encyclopaedia Iranica defines zār as a “harmful wind (bād) associated with spirit possession beliefs in southern coastal regions of Iran. In southern coastal regions of Iran such as Qishm Island, people believe in the existence of winds that can be either vicious or peaceful, believer (Muslim) or non-believer (infidel).”41Maria Sabaye Moghaddam,“ZĀR” in Encyclopaedia Iranica Online, accessed July 5, 2023, https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/zar. The word zār itself is derived from the Arabic word “zār,” which means alternately “visitation” or “affliction.”42For more discussion on zār, see: W. O. Beeman, “Perso-Arabic and Islamicate Healing Rituals of the Iranian Cultural Sphere” in W. O. Beeman (Ed.), Islamicate Rituals: From Iran to Indonesia (Brill, 2015), 77–100; Robert Lawrence Friedman, The Healing Power of the Drum (Barrytown, NY: Station Hill Press, 2000); Mohammed Hassen, “The Spirit Possession Tradition in Oromo Society,” Journal of Ethiopian Studies, 23, no. 2 (1990): 1-23; Steven J. Heine, Cultural Psychology: Understanding Human Behaviour in Cultural Context (W. W. Norton & Company, 2016).; Lindsay Jones, ed., Encyclopedia of Religion, vol. 14, 2nd ed. (Macmillan Reference USA, 2005), 1056.; William S. Sax, Possession and Exorcism in the Modern World (Polity Press, 2002). According to Taghi Modarressi, the name zār is Persian and was applied to the cult when it was introduced in southern Iran by black sailors from the south-east coast of Africa in the sixteenth century.43Taghi Modarressi, “The Zar Cult in South Iran,” in Trance and Possession States, ed. R. Prince (Montreal, 1968), 149. However, as Richard Natvig argues “According to the Ethiopian origin theory the Zār cult was thought to have been introduced into the Middle East by female Abyssinian slaves. All of these theories are marred by speculations, uncritical use of sources, or self-contradictions, and must be rejected. The ultimate origin of the Zār cult is open to conjecture.”44Richard Natvig, “Oromos, Slaves, and the Zar Spirits: A Contribution to the History of the Zar Cult,” In The International Journal of African Historical Studies 20, no. 4 (1987): 685. https://doi.org/10.2307/219657.

Contradictory as its origins may be, the traditional healing ritual of zār is still practiced in some communities on Qishm Island. Primarily performed by women, the ritual is believed to involve communication with jinn, or supernatural beings, in order to seek their assistance in curing physical and psychological ailments. The practice of zār has become an essential part of the cultural identity of the island’s inhabitants and is deeply intertwined with local beliefs about health, illness, and the supernatural. The zār ritual is performed using traditional instruments such as the daf (a frame drum instrument also known as Dāyirah and Riq) and nay (an end-blown flute that figures prominently in Persian, Turkish, and Arabic music), and is accompanied by songs that address specific spirits. During the zār ritual in Qishm, women gather to sing and dance while a woman who is believed to be possessed by a jinn is brought before them.45W. O. Beeman, ed., Islamicate Rituals: From Iran to Indonesia (Brill, 2015), 81. The women performing the zār then attempt to communicate with the jinn through song and dance, offering it gifts and asking for its help in curing the possessed woman’s illness.

Figure 18: Hāfizī and his two friends playing music around the fire before another earthquake. A Dragon Arrives! (2016), Mānī Haqīqī. Accessed June 6, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2hGuvh2Du-I (00:55:00)

As I described earlier, Hāfizī’s journey takes a captivating turn when he indulges in the psychedelic cigarette. This peculiar experience leads him to partake in a zār session on the enchanting island of Qishm, where his consciousness expands into a realm beyond the ordinary. Within this supernatural world, he unravels the hidden threads of the SAVAK conspiracy. One particular belief that holds sway on the island is the existence of jinn, ethereal beings said to possess certain individuals. As Hāfizī ventures deeper into this enigmatic realm, he discovers that the jinn’s influence was intricately intertwined with the island’s inhabitants. In a mesmerizing scene, Hāfizī and his two trusted companions gather around a crackling fire under Qishm’s night sky (see Figure 18). They conduct a trance-like performance followed by another earthquake. As seekers of truth, they are united in their pursuit of the unraveling of the SAVAK conspiracy and find themselves on the cusp of extraordinary things—zār, a jinn-stricken cemetery, and the Azhdahā—the dragon—and the earthquake cracks caused by its awakening.

JinnThe concept of jinn has played an essential role in Islamic culture and mythology for centuries. Pre-Islamic Arabian belief systems often associated jinn with natural phenomena such as storms and earthquakes, and, with the advent of Islam, the concept of jinn became integrated into Islamic beliefs and practices. Jinn are believed to be supernatural beings created by Allāh from smokeless fire, granted free will and the ability to choose between good and evil.46In Quran, Surah Al-Hijr, verse 27, Allāh says: “val-jānna khalaqnāhū min qablu min nāri al-samūm.” (And the jinn We created before from scorching fire) (Quran 15:27); Also, in Surah Rahmān (55), verse 15 Allāh says: “va khalaqa al-jānna min mārijin min nārin.” (And He (Allāh) created the jinn from a smokeless flame of fire) (Quran 55:15). According to popular tales, jinn possess the extraordinary ability to transform into humans or animals, and are believed to reside within every imaginable lifeless object—be it stones, trees, or ancient ruins. They also dwell beneath the earth, in the vastness of the air, and even within fire. Despite sharing similar bodily needs as humans, jinn are not bound by physical limitations and can be killed. They take pleasure in exacting punishment upon humans who have caused them harm, whether intentionally or unintentionally, and are believed to cause various illnesses and accidents. However, those individuals who possess knowledge of the proper magical rituals can harness the power of the jinn to their own advantage.47“Jinni,” Encyclopaedia Britannica Online, accessed July 11, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/topic/jinni

Jinn are thought to inhabit a world parallel to humans and to possess supernatural powers, including the ability to influence human affairs and perform magic. However, the portrayal of jinn in cinema, particularly in Hollywood and Disney, has been heavily influenced by Orientalism, perpetuating narrow views and stereotypes of Middle Eastern culture.48It’s worth noting that, while the stereotypical depiction of characters like jinn (or a “Genie”) in Disney’s Aladdin has been wrong, the film still makes the concept available. While Middle Eastern cinema often portrays jinn as mischievous or malevolent, Hollywood’s portrayal ranges from appropriating friendly genies to more sinister beings. These portrayals can oversimplify the complexity and diversity of magic in these originating cultures, creating further misunderstanding and misrepresentation and further exacerbating such negative stereotypes. Despite this, the concept of jinn remains an important aspect of Islamic mythology and culture, reflecting the belief in the goodness and diversity of the natural world. Anthony DeStefano discusses the jinn, particularly their ability to transform, and considers them as “shape-shifters” that can transform into “werewolves, bigfoot, and the Loch Ness monster.”49Anthony DeStefano, The Invisible World: Understanding Angels, Demons, and the Spiritual Realities That Surround Us (Image, 2017), 56. Considering the reference to supernatural elements such as jinn in the film, the strange creature living under the cemetery can be understood to be a jinn which has shifted into the form of a strange animal—namely, a dragon with huge scales. These sorts of transformations are said to be achieved through the jinn’s mastery of “magic and illusion”—qualities notably shared by the medium of cinema itself which, I suggest, can be thought of as a jinniology of cinema.50It should be noted that the various implications of jinn depend on the particular interpretation of scholars and sources in Islamic tradition. Notably, the film weaves together these diverse, supernatural elements including belief in and the practices of magic, ethnic superstitions, and jinn exorcism. Overall, this weaving establishes strong associations with the making of talismans in the form of pictures and words, especially in regions such as Qishm, and talismans are inseparable from Rammālī (fortune-telling) and duā-nivīsī (magic prayer inscription) in Southern Iran specifically.Importantly, the film’s use of magical and talismanic elements serves as a powerful metaphor for the transformative potential of art and cultural exchange, while also offering a critique of the limitations and challenges facing contemporary Iranian society, such as censorship and the oppression of alternative ideas. In this way, Haqīqī’s dark comedy can be seen as a remarkable exploration of the role of abortive art and culture and as a symbolic gesture towards the potentiality of renewal of Iranian society. In order to do so, the film employs the figure of a dragon—a mythic creature which interestingly originates in both ancient Greek and Chinese traditions—presenting the beast as both an alien and traditional, mythological creature with uncanny attributes. A creature that is seemingly asleep yet awaiting the right moment to awaken, arise, and foment great change against all the odds! Azhdahā (Dragon)

Over time, through cross-cultural interactions and other forms of cross-pollination, similarities and connections emerged between the depiction of the dragon in Chinese tradition and the mystical creature known as the Sīmurgh in Persian culture.51The word “dragon” has its etymological roots in the Greek term “drakon” (genitive drakontos), which translates to “serpent” or “giant seafish.” This term is derived from the strong aorist stem of “derkesthai,” meaning “to see clearly.” The connection to “the one with the (deadly) glance,” suggests the notion of the dragon possessing a vigilant or penetrating gaze. This concept aligns with the dragon’s role in literature and traditions found in Persian and Chinese cultures, where it is often depicted as a guardian of valuable treasures. These themes have permeated both classical and contemporary works of literature and cinema, capturing the fascination and imagination of audiences. See: Harper Douglas, “Etymology of Dragon,” Online Etymology Dictionary, accessed on June 10, 2023, https://www.etymonline.com/word/dragon. The Sīmurgh, which translates to “Thirty Birds,” is prominently represented in Shāhnāmah (The Book of Kings, 977 to 1010 CE), an epic poem by the Persian poet Firdawsī (931-1025). Additionally, it is featured explicitly in The Conference of the Birds or The Speech of the Birds (Mantiq-u-Tayr), a mystical, allegorical poem composed by the Persian mystic and author Farīd ud-Dīn ʿAttār Nayshābūrī (1145-1221). These cross-cultural influences and poetic works have contributed to the interconnectedness between the two mythological creatures.

For instance, the Sīmurgh tale has multicultural origins, as ʿAttār’s poem spread in influence due to the Mongol invasion of Persia (1219-1221). Specifically, the tale’s illustrations were strongly influenced by Chinese painting, and ʿAttār wrote about Chinese artists and philosophers, as in the tale of the contest between the Greek and Chinese painters.52Lily Anvar and Dick Davis, The Canticle of the Birds: Illustrated Through Persian and Eastern Islamic Art. Farîd-ud-Dîn Attâr (Paris: Diane de Selliers, 2013), vii. While the Chinese dragon and Sīmurgh are distinct creatures from different cultural traditions, they share certain characteristics and symbolism. In Iran, skilled miniature artists adeptly integrated and appropriated the Chinese dragon into Nigārgarī (Persian miniatures) in the illustrations in Persian classical mystical literature, giving rise to the myth of the Sīmurgh. Further, the Chinese dragon and the Sīmurgh both hold prominent positions in their respective mythologies, both possessing a long history and associations with auspicious qualities and spiritual significance. “In Chinese mythology, the dragon has many forms symbolizing clouds, earth, intelligence, power, sovereignty, water.”53Gertrude Jobes, Dictionary of Mythology, Folklore and Symbols (Scarecrow Press, 1962), 468. However, in Persian mythology, it is sometimes equated with other mythological birds such as the phoenix (Persian: quqnūs) and the Huma Bird (Persian: humā), which further situates the Sīmurgh as a divine entity and consequently, “[i]n classical and modern Persian literature the Sīmurgh is frequently mentioned, particularly as a metaphor for God in Sufi mysticism.”54Hanns-Peter Schmidt, “Simorḡ,” in Encyclopaedia Iranica Online, accessed January 4, 2024, https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/simorg; Regarding the phoenix and the humā, see: Juan Eduardo Cirlot, A Dictionary of Symbols (Courier Dover Publications, 2002), 253.

Thus, as a symbol long associated with Persia (through its association with the Sīmurgh), what are we to make of the dragon in this film and its meaning today? What interpretation are we being asked to make, particularly regarding its political relevance?

For over fourteen hundred years, Iran has endured the rule of despotic regimes, their oppressive grip often tightening even further with each passing era. However, within this oppressive governing apparatus, there has been conscious and unconscious political drives at work in Iran post-revolution; there lies a dormant energy, waiting to be unleashed through the cracks and changes that inevitably occur. The last four decades, marked by the Islamic Revolution of 1979, have only intensified this oppression, burdening the people of Iran with immense pressures and hardships. Their yearning for liberation and respite has become a powerful force, evident in the multitude of anti-government protests that have emerged in various forms. For example: the July 8, 1999 Tehran University students’ riots; the 2009 Green Movement (between June 2009 and February 2010); the 2017-18 Economic Protests; the 2019 Price Hike Protests; the January 11, 2020 Protests; and the recent formation of the Zan Zindigī Āzādī – Jin, Jīyān, Āzādī – movement (i.e., Woman, Life, Freedom) as a result of the tragic death of Mahsā Amīnī—widely believed to have occurred at the hands of the morality police—on September 16, 2022.55“The Iran Primer,” United States Institute of Peace, May 30, 2023, accessed June 10, 2023, https://iranprimer.usip.org/blog/2019/dec/05/fact-sheet-protests-iran-1999-2019-0.

The dragon in Haqīqī’s film can thus be understood as a representation of the long-suppressed, pent-up passive-aggression held by the Iranian people due to the regime’s oppression—an increasingly volatile, explosive feeling of resistance and resentment that will inevitably manifest itself in due course, regardless of attempts to impede its emergence. Notably, the landscapes depicted in Haqīqī’s film, particularly the rugged scenery of Qishm Island and the cemetery, have symbolic resonance with the dragon’s exploding skin scales. The landscape becomes a canvas upon which the dragon’s emergence and the accompanying release of accumulated tension unfolds, painting a powerful and evocative picture of societal transformation and longing for freedom in Iran.

In this way, the dragon in Haqīqī’s film can be interpreted further as an example of what the prominent cultural critic and Marxist theorist Fredric Jameson conceptualized as the “political unconscious.”56 Fredric Jameson, The Political Unconscious: Narrative as a Social Symbolic Act (London: Methuen, 1981).

Inspired by Jameson’s concept and its expansion, the idea of “political subjectivity” emerged in the social sciences and humanities, reflecting the intersection of several traditional disciplines such as anthropology, political theory, philosophy, and psychoanalytic theory. Jameson argues that cultural texts, such as literature and film, are not simply aesthetic creations but are deeply intertwined with politics and ideology. He suggests that texts carry implicit or unconscious political messages that reflect and reproduce a given society’s dominant ideologies and power structures: “The political unconscious insists on the priority of the social and the historical, and on the priority of the collective over the individual.”57Jameson, The Political Unconscious, 17. Jameson argues against a purely interpretive approach to cultural texts by proposing a symptomatology, which involves examining the symptoms or signs within the text to uncover the underlying political ideologies and structures: “The political unconscious, then, is not a hermeneutic, but a diagnostic instrument, a way of reading the symptoms of the collective political body, a way of grasping the meaning of the symptoms and of the underlying disease.”58Jameson, The Political Unconscious, 20. He argues that just as individuals may have repressed desires and thoughts in their personal unconscious, societies and cultures also possess a collective unconscious that contains suppressed or marginalized political forces.59In regard to the Azhdahā’s / dragon’s emergence referring to the potential forces of Iranian “political unconscious” and how it can break through any suppressive system, Iranians may recall The Tale of the Snake-Catcher in the third book of Masnavī Ma‛navī by Rumi which metaphorically references Azhdahā’s awakening in unsettling situations. The tale recounts the story of a serpent charmer who ventures into the mountains to catch a snake. There, he discovers a slumbering dragon buried in the snow, mistaking it for dead. Filled with the desire to stage a captivating spectacle and reap the financial gain, the charmer transports the seemingly lifeless creature to Baghdad. As news spreads, people flock from all directions to witness this extraordinary sight, believing the huge serpent is dead. However, as the radiant sun of Baghdad warms the despondent and hunched dragon, it gradually revives and begins to stir. The crowd panics, scattering in fear as the enraged dragon breaks free from its restraints and embarks on a destructive rampage. The dragon immediately kills the serpent charmer, and the ensuing chaos results in the unfortunate death of many who were caught in the overcrowded frenzy. In this allegory by Rumi, the dragon symbolizes human “nafs” (whims), which, if not carefully managed, can lead individuals into trouble. It also offers an interpretation of the dragon as representing the realm of the “unconscious,” wherein desires, aggression, and intricate psychological complexities lie dormant. In a famous line from the tale (in form of a long poem), Rumi says: “nafsat azhdahāst, ū kay murdah ast?” (Your whim is a (sleeping) dragon which is not dead), see Rumi,

“Hikāyat-i mārgīr [The Tale of the Snake-Catcher],” Ganjoor, accessed June 6, 2023, https://ganjoor.net/moulavi/masnavi/daftar3/sh37 Following Jameson, the cemetery depicted in the film where the fatalities from an old war were buried long ago can be thus metaphorically understood as akin to a repository of memories and therefore a vital, important site of this Iranian “collective” unconscious—a potent location in which disturbing recollections are gathered and concealed. In response to this latent potency, censorship and other defense mechanisms (both in the film and in reality) attempt to suppress these memories as they contain elements of truth that threaten to unsettle dominant power structures if brought to light. However, the unconscious, collective mind continually strives to emerge and enter the conscious realm. In this context and in relation to the film, Hāfizī, responsible for providing a report on the death of the exile, seeks to uncover something hidden from him as much as from the wider, Iranian consciousness; however, the pursuit of truth comes at a high cost.

During the SAVAK’s investigation, an intriguing connection between the earthquake and a peculiar creature beneath the cemetery’s surface is revealed by Shukūhī to Jahāngīrī, one of the other SAVAK agents. Shukūhī states,

I have already explained this. The cracks caused by the earthquake were only present in the cemetery. This is highly unlikely for an earthquake. You see, earthquakes typically have a wide-ranging impact. If there had been an earthquake here, the ground would have shaken for several thousands of kilometers. We would have observed signs of its occurrence, but in this case, the effects were limited solely to the cemetery.60A Dragon Arrives! 00:27:59.

Furthermore, Shukūhī elaborates on their experience during another earthquake, recalling how they ventured in the Impala to survey the area surrounding the cemetery. They discovered five new cracks, but interestingly, “Two hundred meters away from the cemetery everything was fine.”61A Dragon Arrives! 00:55:25. In addition, Shukūhī shares an account of the Indian individual who spoke to him in German before his death after being pulled out from one of the cracks. Shukūhī recounts the encounter, and translates into Farsi what the Indian man said to him in German: “I saw a strange animal with scales as black as tar and red eyes like molten coal.”62 A Dragon Arrives! 01:04:40.

In combination, the film’s eye-catching landscapes appear to metaphorically settle upon the unyielding skin of a camouflaging dragon which is awakening from a centuries-long slumber of fourteen hundred years. The tension accumulated during this dormant Islamicate phase is now being released as the dragon shakes off its camouflage, unraveling its proper form against the backdrop of Qishm’s scenery and landscape. The rough terrain, with its untamed features and rugged beauty, reflects the underlying tumultuous state of Iranian society, poised for a transformative and cathartic release. Through these visual and symbolic elements, Haqīqī displays a compelling depiction of the suppressed desires and aspirations of the Iranian people, embodied by the dragon, as they strive for liberation from the oppressive regime that has metaphorically buried them in silence for over four decades in a cemetery.

Figure 19: Hāfizī and Shukūhī fly colorful balloons into the sky to which a camera is attached for taking photos. A Dragon Arrives! (2016), Mānī Haqīqī. Accessed June 6, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2hGuvh2Du-I (00:35:43)

Notably, the portrayal of Qishm Island’s beautiful and pristine—if coarse—landscape serves as a visual representation of their very allure, exemplified by Hūman Bihmanish’s cinematography skills and underscored by the film’s haunting ambiance. For example, no audience member can ever forget the flight of colorful balloons that Hāfizī and Shukūhī release into the sky. Floating over the breathtaking landscape to take photos of the cemetery from above, this combination of balloons and panorama evokes a deeply poetic sentiment that can be understood as the visual equivalent of hope and renewal (see Figure 19).63A Dragon Arrives! 00:35:55. The inclusion of such visually striking scenes and the adept use of long shots contribute to the film’s overall visual appeal while effectively supporting its themes of mystery and intrigue.

Conclusion

In A Dragon Arrives!, alongside its many interwoven elements of superstition, fragmentation, archives, and intertextuality, careful attention to costume and make-up design works in harmony to create a believable and immersive world, allowing the audience to more fully engage with the film. Additionally, the musical composition by Christophe Rizā‛ī plays a crucial role in setting the tone and foreshadowing the film’s suspenseful nature. Rizā‛ī’s innovative fusion of electronic pop and mouth-harp with traditional zār music creates a unique auditory experience, effectively heightening tension and anticipation and complementing the visual and narrative aspects.

For some, Haqīqī’s film might be a mere attempt to create a pleasant cinematic experience by presenting jumbled sequences and orchestrated interview fragments that have little to do with the social reality of Iran. However, such an impression ignores the significance of the many artworks which it incorporates, especially films and performances, in influencing—if not directly helping to fashion—the concepts concerning the larger social, cultural, and historical context in which they are situated and produced. Furthermore, Haqīqī’s skillfully crafted assemblage of concepts within the intertwined network of (sometimes) bizarre pieces are appealing enough to effectively stimulate alternative dialogues surrounding Iranian history and politics. Such simplistic reductions of the film to mere entertainment also ignore Haqīqī’s work with cinema as a concept-making machine—or in Haqīqī’s own words a “meaning-making system.”64See: “Nishast-i khabarī-i Azhdahā vārid mīshavad bā ḥuzūr-i Mānī Haqīqī,” Aparat, February 9, 2016, accessed August 28, 2023, https://www.aparat.com/v/RQhKB (translated by the author). Such reductive views also overlook the film’s potential to spark meaningful discussion and reflection on Iranian culture and identity and its complex politics and relationship with the world beyond its borders.