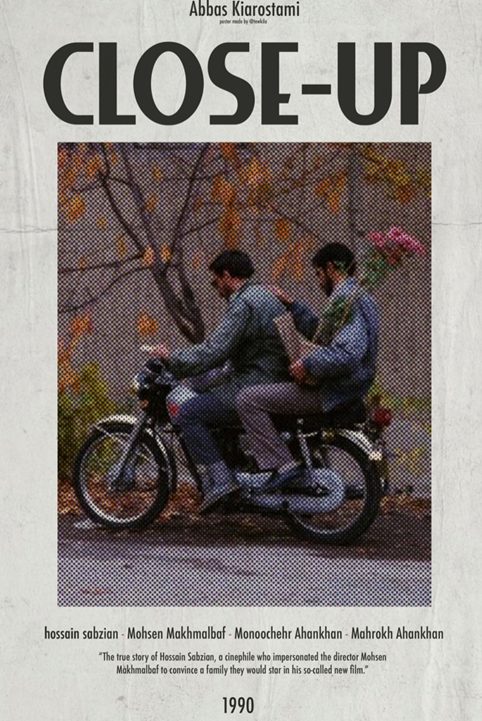

Close-Up (1990)

Figure1: The Film Poster Close-Up (1990), ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī.

“The struggle against the established order is always individual, a struggle which each must engage in on his account by making use of whatever resources he has at his disposal, whether material or symbolic and by developing his strategies in the light of his own experience.”

—Pierre Bourdieu1Pierre Bourdieu, “The Forms of Capital,” In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, ed. John G. Richardson (Greenwood Press, 1986), 241.

“If I had the courage to protest . . . I would use filmmaking as a tool to fight all injustice.”

—Husayn Sabzīyān2Close-Up Long Shot, 00:07:09; For watching this documentary—which is about Sabzīyān’s character and life after Kīyārustamī’s film—with English subtitles see, Close-Up Long Shot, dir. Muslim Mansūrī (1996), accessed 05/08/2023, www.youtube.com/watch?v=w4NOseV8to8.

The Story Behind Close-Up

In 1988, Husayn Sabzīyān, a cinephile in Tehran resembling the famous Iranian filmmaker Muhsin Makhmalbāf, took advantage of this and introduced himself to the Āhankhāh family as the well-known director. Sabzīyān enters the Āhankhāh’s home under the pretext of making a film. On the first day, the fake Makhmalbāf asks Mihrdād, the son of the family who is interested in cinema, to take on a role in the movie he is planning to make, and which would use the Āhankhāh house as a location. On the second day, they rehearse movie scenes. However, the father of the family, who is suspicious of Sabzīyān from the beginning, reveals Sabzīyān’s true identity with the help of his friends from Iranian TV and Husayn Farāzmand, a reporter with Surūsh magazine. Sabzīyān is arrested on the third day and sent to court. Following an investigation into the case and after obtaining consent from the Āhankhāh family, in addition to a commitment from Sabzīyān himself, the case is closed in court. On the day Sabzīyān is released, Muhsin Makhmalbāf visits him, and the two of them go to the Āhankhāh home to ask for forgiveness and reconciliation.

Kīyārustamī’s films often center around ordinary or marginalized characters who embark on extraordinary journeys of their own volition amidst the chaos of life: from the teenager in Musāfir (The Traveler, 1974) to the middle-aged man in Taʻm-i gīlās (Taste of Cherry, 1997), their quests for personal fulfillment—whether it be witnessing a football match or finding someone to bury them after their suicide—highlight the depth and complexity of human desires. Additionally, Kīyārustamī’s early work, such as Mashq-i shab (Homework, 1989), reveals his fascination with cinéma vérité and his exploration of power dynamics within the educational system of 1980s Iran.

In the case of Close-Up, Kīyārustamī deviated from his original plan to make his next film, Pūl-i Tūjībī (Pocket Money, a film which was never made), upon learning about Sabzīyān’s fraudulent impersonation. Intrigued by the incident, he created a film without a prewritten script. Close-Up showcases a unique blend of fiction and documentary, employing cinéma vérité techniques to present the real-life participants portraying themselves. The film primarily revolves around Sabzīyān’s introspections, revealing his deep love for cinema, admiration for Makhmalbāf, and the sense of authority he gained by pretending to be the acclaimed director. Kīyārustamī masterfully intertwines re-enactments, an evocative interview with Sabzīyān, and actual trial footage, blurring the boundaries between reality and fiction.

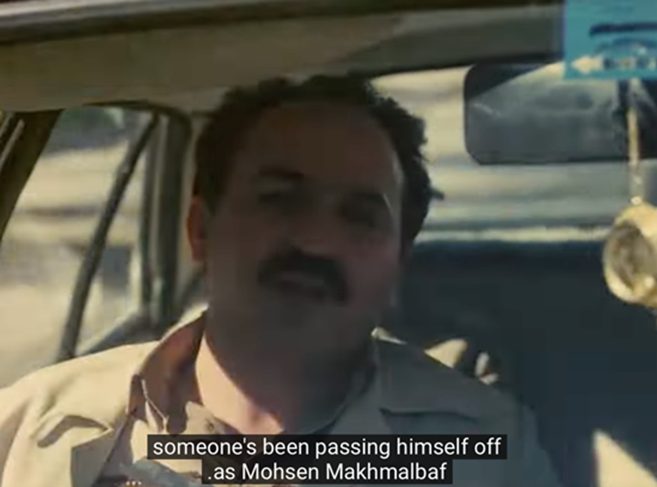

The film opens with a scene in which the reporter Husayn Farāzmand is in a car with the driver and two police officers, about to set off to the Āhankhāh home to arrest Sabzīyān (after making sure that he is not the real Makhmalbāf). The film then uses flashbacks to show how Sabzīyān met Mrs. Āhankhāh while traveling on a bus. He had pretended to be Makhmalbāf and impressed her with his knowledge of cinema. As the story unfolds, we see how Sabzīyān’s deception is discovered, and the family members become angry and call the police. Kīyārustamī appears in the film as a filmmaker documenting real-life events and encourages Sabzīyān to talk about his motivations in court for impersonating Makhmalbāf. Sabzīyān eventually confesses his guilt, and the Āhankhāh family forgives him.3Jonathan Rosenbaum’s co-commentarian Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa says the rumor is that the family initially did not withdraw their complaint against Sabzīyān but later agreed to do so for the film. She also says that Sabzīyān points out that, because of Close-Up, the family did get to be in a film as he promised them. See “Close-Up (1990, Abbas Kiarostami),” Brandon’s movie memory, August 26, 2016, accessed May 04, 2023, https://deeperintomovies.net/journal/archives/tag/abbas-kiarostami.

Figure 2: A still from Close-Up (1990), ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ep3595lzTJY (00:01:20).

According to the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu (1930–2002), individuals must use their resources and experiences to challenge the established order and carve out a space for themselves. This can involve developing new ways of thinking and acting that challenge society’s dominant norms and values.4Pierre Bourdieu, Outline of a Theory of Practice (Cambridge University Press, 1977), 15. Sabzīyān is a unique example of such an effort, as evidenced by his passion for art and storytelling, all the while distorting class hierarchy to gain power and confidence. As a result, Close-Up creates new concepts for identity, power relations, subversion, cinema, authenticity, and storytelling. The film also uses engaging cinéma vérité aesthetics such as interviews and self-reflexivity to ask viewers to think about Sabzīyān’s story and create meaning. Consequently, Close-Up blurs the lines between documentary and fiction and questions traditional notions of authorship and authority in cinema. This article thus explores Close-Up and especially Sabzīyān’s character and his motivations in light of what French philosophers Gilles Deleuze (1925-1995) has termed “the power of the false,” and, in addition with Félix Guattari (1930-1992), their schizoanalytic approach. The article also touches upon the importance of oral storytelling in encouraging interpretation and shaping collective and individual subjectivities. Overall, this article argues that Close-Up offers important insights concerning how to resist and imagine alternative modes of being and becoming in the face of class struggle and inequality.

The Power of the False

In Cinema 2: The Time-Image, Gilles Deleuze introduced the concept of “the power of the false.”5Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2: The Time-Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta (University of Minnesota Press, 1989), 126. In simple terms, this refers to a character’s storytelling prowess, his/her talents for forgery whether in a novel or a film. According to Deleuze, the false or the fictional has a unique capacity to challenge existing structures of reality and to create new meanings. Falsehood allows creators to escape from the constraints of the natural world and envision new possibilities. However, Deleuze does not suggest that we must deceive or mislead through falsehood for personal benefit, something that politicians usually do. He asks us instead to forge stories that subvert the dominant system of meaning-making. Additionally, in Difference and Repetition, Deleuze invokes the concept of “difference” to illustrate the power of the false and argues that it is not simply negative or the opposite of identity. Instead, it is a positive force that generates new and diverse forms of existence: “The false is the power of difference positively employed, the power of difference to create or invent.”6Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, trans. Paul Patton (Columbia University Press, 1994 [1968]), 29. Following their theory, Sabzīyān presents a fascinating case study concerning the positive potential and power of falsehoods.

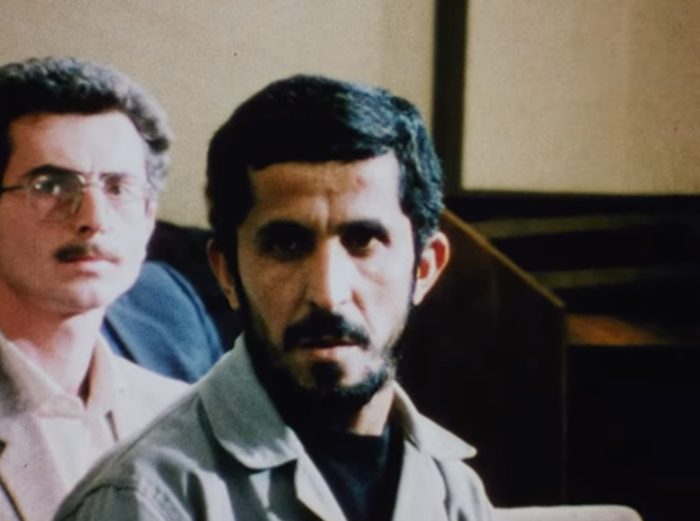

Although there are strong elements of deception in Sabzīyān’s approach to the Āhankhāh family, his sincere obsession with cinema makes his deception resemble the innocent ruses that children in many of Kīyārustamī’s films partake in to achieve their goals. For instance, early in the courtroom scene, when Kīyārustamī asks Sabzīyān about his obsession with film, the latter expresses his admiration for Makhmalbāf’s Bāysīkil’rān (The Cyclist, 1987) and its central character. Sabzīyān asks Kīyārustamī to send a message to Makhmalbāf: “Tell him that I live with The Cyclist.”7Close-Up, 00:24:33. All timestamps in this article adhere to the DVD edition of ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī’s film Close-Up (1990), released by The Criterion Collection (Janus Films). The film version referenced in this analysis has been sourced from the aforementioned DVD uploaded on the YouTube platform: Close-Up, dir. ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī (1990), accessed 05/08/2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ep3595lzTJY Later in the court, Sabzīyān refers to Qāsim Jūlāyī, the protagonist in Kīyārustamī’s early film Musāfir (The Traveler, 1974), and explains how the kid takes photos of children with an empty camera to raise money for purchasing a ticket for a football match in a stadium. When Qāsim travels to Tehran and reaches the stadium, he decides to take a nap which turns into a deep sleep for the whole game! To which Sabzīyān concludes: “Like him, I have been left behind.”8Close-Up, 00:40:35.

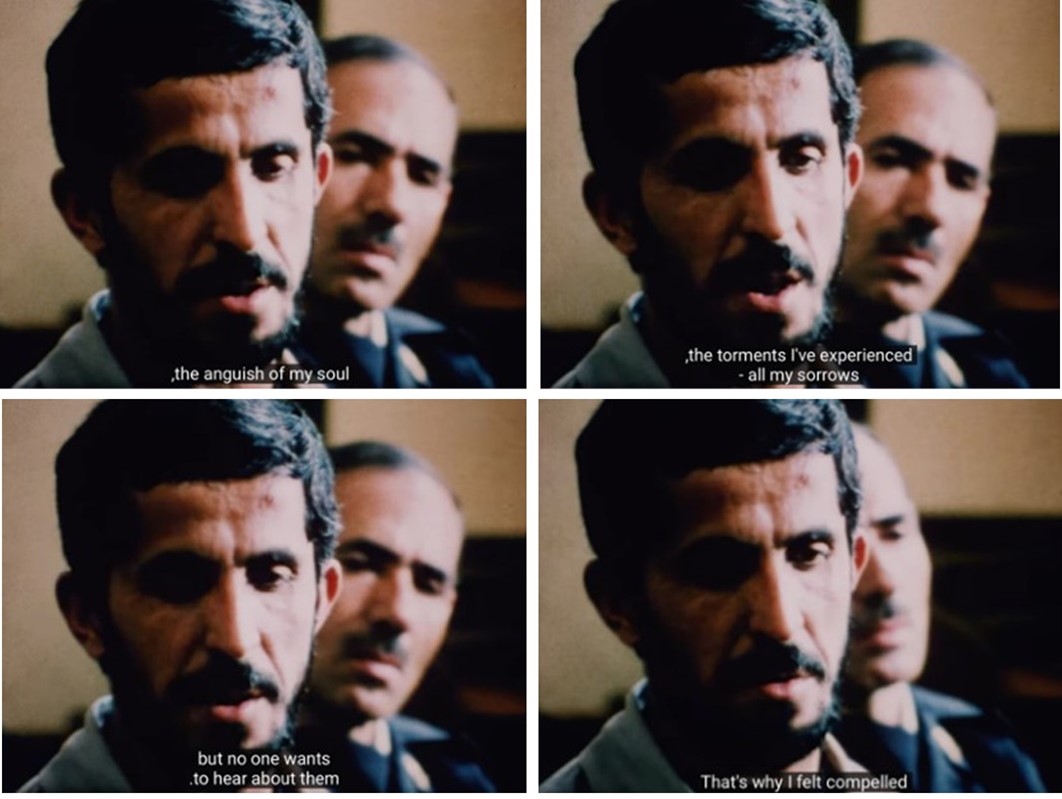

Figure 3: A still from Close-Up (1990), ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ep3595lzTJY (00:23:55).

In the documentary film, Close-Up Long Shot (1996) by Muslem Mansūrī and Mahmūd Shukrallāhī, the character of Sabzīyān is explored along with his deep fascination with cinema. Sabzīyān’s complex emotions are evident as he reflects on his deceptive actions. He recounts, for instance, an encounter on a bus with the mother of the Āhankhāh family who mistook him for the renowned filmmaker Makhmalbāf, prompting Sabzīyān to impulsively introduce himself as the writer and director of Makhmalbāf’s acclaimed film The Cyclist.

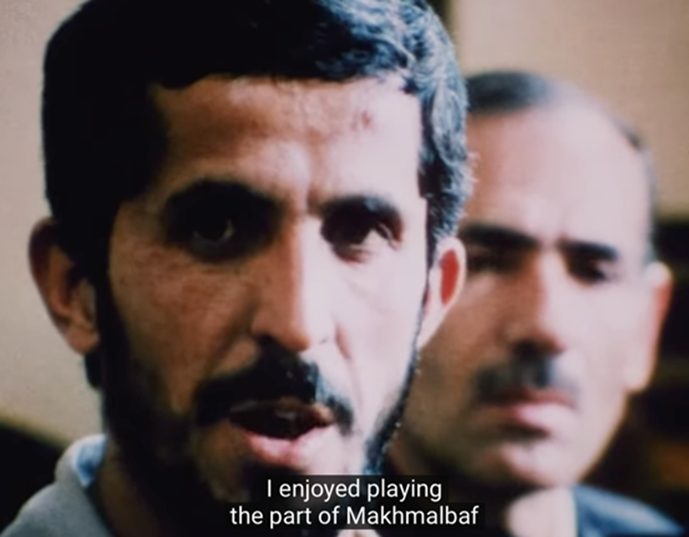

Figure 4: A still from Close-Up (1990), ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ep3595lzTJY (00:33:07).

At that point, I could feel that the clothes I was about to put on were too tight. Too tight for me. But the pleasure that the role gave me made me continue. The clothes burst apart at the very moment that I was arrested. The buttons popped off, and I emerged. I wore it in every scene when I was playing the part of Makhmalbāf.9Close-up Long shot, 00:11:51.

Sabzīyān’s recollection of this encounter reveals conflicting feelings. On the one hand, he expresses a sense of satisfaction with his deceitful act. However, he also conveys a particular disappointment, alluding to the feeling that the role he assumed was becoming constricting—as he says, like clothes that were too tight. Despite this, the pleasure he derived (like a child) from embodying the role compelled him to continue the charade.

In an interview with Iranian-American filmmaker and scholar Jamsheed Akrami, Kīyārustamī refers to the same scene and asserts that Close-Up’s character is the extension of other child characters in his previous films, relating Sabzīyān’s fraud to the malfunction of the Iranian educational system:

While Close-Up has nothing to do with children, I would like to draw your attention to references in the film that the actor, Husayn Sabzīyān, makes and his belief that he is the kid in Musāfir who “has been left behind.” And, in my opinion, the kid in Musāfir is in a way similar to the children in my other film, Mashq-i Shab [Homework, 1989]; and all the children in Mashq-i Shab are the kids in my other film Khānah-yi dūst kujāst [Where Is the Friend’s House?, 1987]. I think they are so similar that they are just grown-up versions; I mean, one can easily see that the thirty-something Husayn Sabzīyān is one of the children in Mashq-i shab who has grown up to this point, which is the result of that kind of education, training, and of society at large.10Jamshīd Akramī, “Guftugū-yi Jamshīd Akramī bā ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī dar bārah-yi film-i Kluz-āp (Namāy-i Nazdīk) [Jamsheed Akrami’s conversation with Abbas Kiarostami about the film Close-Up],” Vista News Hub, accessed August 08, 2023, https://vista.ir/w/a/21/s9wjv (The translation from Farsi into English is by the author).

Although, for both the character of Qāsim Jūlāyī and the actor/person Husayn Sabzīyān, falsehood fails to help them achieve their goals, they both take a chance on its empowering potential. Falsehood, for instance, enables Sabzīyān to generate a new identity with temporary power and creative potential for filmmaking. They both use deception and falsehood as trickery in their own personal fairy tales!11Sabzīyān’s childish character and his false assumptions and deeds are also seen in his interview in Muslim Mansūrī’s Close-Up Long Shot:

. . . that irrational act [impersonating Makhmalbāf] proved my love for film I’m satisfied. Because I made one of my dreams come true. I was Makhmalbāf for four days. I remember Orson Welles’ advice to his students who wondered how to find the money for their films. “Steal it,” he said. “At least you will fulfill your hopes.” Who’s to blame? I may be one of the cinema’s victims. I intended to devour cinema, and it ended up devouring me. It didn’t appreciate me. I still advise all cinema lovers that if they can’t achieve their dreams, the way I see it, do as Orson Welles said: “Steal the money.” See, Close-up Long shot, 00:13:17.

Figure 5: A still from Close-Up (1990), ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ep3595lzTJY (01:00:50).

Moreover, Kīyārustamī’s engagement with and deliberate use of falsehood and imperfection, such as the fake glitch in his sound recording at the end of Close-Up, can be traced to some of his other works. In particular, Kīyārustamī’s use of non-professional actors, randomness, spontaneity, and improvised dialogue reinforces the importance of falsehood and imperfection. He believed that this approach helped to create a sense of authenticity and realism in his work, which allowed the audience to connect more deeply with the characters and the story. In an interview with Jonathan Rosenbaum about Close-Up, Kīyārustamī references the French Impressionist painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s saying, which encourages creative imperfection:

When you film a reality, you must leave room for the unexpected. Renoir once said that when a painter drops his brush, it should become a part of the painting. I believe that if something unexpected happens during filming, we must integrate it into the work, not erase it.12Abbas Kiarostami and Jonathan Rosenbaum, Abbas Kiarostami: Texts and Conversations 1971- 2007 (The University Press of Mississippi, 2018), 27.

Indeed, what could be more unexpected than a man pretending to be a famous director and the story becoming a film with the original deceiver playing himself? In the case of Close-Up, the unexpected runs riot. Sabzīyān distorts the truth to create a false persona, elevating his status to modern myth. He deliberately manipulates the truth and deceives the Āhankhāh family for personal satisfaction, creating a new and more decent identity image of himself. Although deceit can often cause harm or, at the very least, bad feelings, the audience of Close-Up is asked instead to look more closely at the motivations of Sabzīyān and even Kīyārustamī. Sabzīyān’s behavior suggests that he is motivated by a desire for connection and understanding rather than malice, which engages with questions of empathy across social and class divides.

In Close-Up Long Shot, Sabzīyān baptizes himself by attributing the act of manipulation for the sake of fame to almost everyone who was involved in the production of Close-Up:

The only thing that cinema did for me was to portray me as a con artist. If that is the case, everyone’s a con artist. That family [the Āhankhāh family] wanted to use Muhsin Makhmalbāf to gain prestige. That’s a kind of con. Maybe I toyed with their feelings, but their actions speak for themselves. Or that reporter [Farazmand] who wanted to break the story so he could become another Oriana Fallaci, using me as his bridge, his stepladder to success—that’s another con. Even Mr. Kīyārustamī himself, who heard of my case through the reporter . . . found an interesting subject and won international acclaim for it; when you think of it, he conned me. He’s a con artist too. I think that Close-Up depicts the natural course of events I set in motion. For example, I promised my family that I would make them appear in a film. Well, they did. What I promised happened. And when I saw Kīyārustamī at work giving them directions, I noticed that the direction I’d been giving was not different from his. The family listened to him the way they’d listened to me. There was no difference between how he directed and how I did.13Close-up Long shot, 00:18:40. In the description of the film on YouTube (originally written in Farsi which I have translated into English), Mansūrī writes:

A few years later, after the release of Close-Up, one-day Sabzīyān desperately came to the office of the Cinema Weekly magazine. He had written a letter against Kīyārustamī and the Close-Up movie. The editor-in-chief of Cinema Weekly refused to publish the letter. Sabzīyān complained that none of the movie magazines were willing to publish his letter. As he was leaving the magazine office, I suggested he participate in an interview documentary that I would make in which Sabzīyān would express his opinion.

A long time after the suggestion, Mansūrī found the opportunity to make the interview documentary Close-Up Long Shot (1996) which Mahmūd Shukrallāhī produced.

If, as Sabzīyān suggests, everyone was engaged in the falsehood, then everyone should be accountable to the law and judged equally. Meanwhile, Sabzīyān’s creative falsehood sparked a series of interviews and encounters that resulted in the making of an intriguing documentary whose authenticity and importance have stood the test of time.

Figure 6: A still from Close-Up (1990), ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ep3595lzTJY (00:28:43).

In his seminal book Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia (2010), the American film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum considers Close-Up “a masterpiece and one of the greatest films ever made.”14Jonathan Rosenbaum, Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia: Film Culture in Transition (University of Chicago Press, 2010), 185. Similarly, Roger Ebert (1942-2013), another acclaimed film critic, admires Close-Up as one of “the most fascinating documentaries” he has ever seen because of how Kīyārustamī reconstructs real events. He further writes: “Kiarostami takes us inside the actual people and events he is filming, and yet there is never a sense that he is manipulating reality. In fact, the film is about the way reality is always being manipulated by everyone involved, including the director and the actors.”15Roger Ebert, “Close-Up.” Chicago Sun-Times (October 14, 1996): 27. As artists usually manipulate their material to produce their artworks, Sabzīyān’s daringly creative imitation of Makhmalbāf can be seen as an opportunity to manipulate elements of reality to create an ideal persona and identity image; in fact, his identity is his artwork. In doing so, Sabzīyān—through Kīyārustamī’s film—offers us a compelling example of the “positive” impact of Deleuze’s conceptions of the “power of the false” and “difference.”

Identity, Social Class, and the Schizo

From Franz Kafka’s Die Verwandlung (The Metamorphosis, 1915) and Rizā Qāsimī’s Hamnavāyī-i shabānah-yi, urkistr-i chūb’hā (Nocturnal Harmony of the Wood Orchestra, 2001) to Roman Polanski’s film Le locataire (The Tenant, 1976), identity crisis, fluidity, and transformation have been essential elements of modern and postmodern literature and art. The concept of identity is always as complex as it is intricate, referring to a person’s various aspects that make them unique and distinguishable from others. Further, identity is how individuals understand and define themselves, including their social roles, sense of self, values, and beliefs. It encompasses factors such as gender, sexuality, race, ability, age, culture, and personal history and can be influenced by internal and external factors. In his book The Ethics of Authenticity (1991), philosopher and influential theorist on the concept of identity, Charles Taylor, argues that identity is not a fixed or predetermined aspect of a person but rather something that is constructed through an ongoing process of “negotiation, reflection, and discovery.”16Charles Taylor, The Ethics of Authenticity (Harvard University Press, 1991), 27. Emphasizing the relationship between social structures and individual agency, the British sociologist Anthony Giddens further contends that identity is not static or fixed but is, in fact, fluid and “continuously negotiated and constructed through social interaction,” as quoted in Naficy.17Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 4: The Globalizing Era, 1984–2010 (Duke University Press, 2020), 54. In this sense, identity is not an unchanging characteristic but rather a dynamic and ongoing process of self-discovery and self-creation. As individuals encounter new challenges, experiences, and perspectives, their identities can change and evolve. In addition, identity transformation can also be empowering and liberating as individuals gain a deeper understanding of the self and their place in the world. Thus, like any imposter, Sabzīyān’s fraudulent identity assists him in his upward mobility from an unknown citizen to a cinematic idol. In this way, Close-Up can be seen as a meditation on the nature of identity caught between what Hamid Naficy describes as the “dichotomy between acting and being that is at the heart of both cinema and moral behavior.”18Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema. Vol. 4, 54. However, the dichotomy can also be described as between being and becoming through the elements of a “schizo’s” desire, to use Deleuze and Guattari’s term, against the system of power in a postmodern world. Sabzīyān’s identity is caught between the two—he passionately tries to “become” Makhmalbāf while being Sabzīyān, one who is unknown and “downtrodden.” “Indeed,” Naficy adds, “Close-Up is entirely about the lie at the heart of cinema, whereby actors pretend to be others, producing a sustained and complex treatise on the morality of the Iranian dichotomy between being and acting.”19Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema. Vol. 4, 195. When asked early in the courtroom scene about the motivation for his wrongdoing, Sabzīyān insists that what we saw of his deed was the zāhir (the outside [act]) which is different from its bātin (the inside [intention]). In combination, zāhir and bātin refer to Islam’s external and internal dimensions. For instance, the Qur’anic zāhir and bātin concepts provide possibilities for the interpretation of the holy verses. Subsequently, the impact of zāhir and bātin has been extended to Islamicate social customs, literature, and arts in Iran and how people interpret them. It is hence unsurprising to witness events, artworks, and behaviors with double meanings that might seem different from what they mean (on the outside) and which thus require careful interpretation (of what is inside). In this light, Sabzīyān’s behavior can be justified as seemingly fraud-like while also being gracefully intended as creative and demonstrative of his love for cinema. We may even take this dynamism of zāhir and bātin in Iran further to the extent that people may perform different split personas in the domestic domain in opposition to how they appear at work, school, and society in general. Thus, the title of Kīyārustamī’s Close-Up, with its “close” observations of Sabzīyān’s character, explores the bātin of Sabzīyān’s wrongdoing.

Meanwhile, it is important to note that Close-Up was made during a transitional time in Iran after immense political upheaval and an eight-year war with Iraq (1980-88); as a result, Iranians were actively questioning their collective identity. Further, it is worth recalling that cinema has been an essential apparatus in shaping modern subjectivity, especially in Iran. Consequently, Sabzīyān’s interpellated identity via cinema helped him fill in the gaps of social divides in Iran—a schizo-like escape from his real self and being entirely unknown, toward becoming, even momentarily, a famous director known to almost everyone in Iran.20Interpellation is particularly associated with the works of Algerian-French Marxist philosopher Louis Althusser. In sociology, it refers to the process through which individuals are called into specific social roles and identities by external forces such as institutions and societal norms. It shapes individuals’ sense of self and subjectivity by assigning them certain roles and expectations based on social categories. Interpellation operates through language, media, symbols, and everyday practices, shaping individuals’ beliefs and behaviors. Critics see it as restrictive, while others view it as essential for social cohesion and identity formation. See: Louis Althusser, “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses: Notes Towards an Investigation,” in Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays, trans. Ben Brewster (New York: Monthly Review, 1971): 85-126.

Sabzīyān’s behavior in the film does not necessarily indicate that he has the psychiatric designation of schizophrenia, and the aim of this article is not to make psychiatric or psychological assumptions or judgments about Sabzīyān based on his behavior in the film. However, his loss of connection with reality and his deluded obsession with cinema produced very real, material consequences for him, such as losing his job, allowing us to explore him in the light of schizoanalysis a la Deleuze and Guattari. Indeed, cinema so deeply possessed him that he was fired from his job as a print-shop worker yet he also convinced himself that he was powerful enough to “become” an artist/filmmaker. According to Deleuze and Guattari’s discussion of schizoanalysis in Anti-Oedipus, Sabzīyān’s distance from reality and the way he uses his desire for cinema to break the boundaries between the real and the fictional make him an appropriate example of a schizo character.21Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Robert Hurley, Mark Seem, and Helen R. Lane (The University of Minnesota Press, 1983). By posing as Makhmalbāf, he can temporarily inhabit a new identity and explore new creative possibilities as a film director. However, his identity theft ultimately leads to his downfall because he cannot sustain the illusion and is eventually caught by the Āhankhāh family.

For instance, Sabzīyān admits that he identifies with Makhmalbāf’s main character in his film The Cyclist, a poor Afghan refugee who decides to demonstrate riding his bicycle in a circle for seven days and nights in order to raise money for his wife’s much-needed, life-saving surgery. The similar pressures of poverty and class difference caused Sabzīyān to create an empowering fictional character that allowed him to feel better about himself and his social position in the world: “It [impersonating Makhmalbāf] gave me self-confidence and they [Āhankhāh’s family] respected me, gave me attention . . . They did whatever I wanted.”22Close-Up, 00:45:04.

To further lean into this schizo-thematic, like a psychotherapist who asks and encourages their patients to freely express their internal complexities, anxieties, pressures, and desires, Kīyārustamī uses cinéma vérité aesthetics to provoke Sabzīyān and to investigate his drives for his fraudulent deed. The director tells Sabzīyān: “This camera is here so you can explain things that people might find hard to accept.”23Close-Up, 00:29:44. Kīyārustamī’s provocation and observations of Sabzīyān’s split personality can thus be seen and understood as a profound method of schizoanalysis in the film.

In his approach as a reporter before and after Sabzīyān’s metamorphosis, Kīyārustamī, too, has one foot in reality (reporting on Sabzīyān’s imposter trick) and one foot in fiction (making a film about this report). The title of the film, Close-Up, also suggests the exploration of desires through close (meta) analysis. Further, and on another level, Close-Up explores the soul and psyche of a Kīyārustamī-esque model: a man who hopes to escape himself and his current identity through (artistic) forgery and who lies in order to transcend toward an ideal one. Indeed, is not the essence of art a kind of transformation of the self as material into an ideal image through the creative process?

Schizoanalysis Close Up

Through schizoanalysis, we can see Close-Up as an exploration of the relationship between creative expression, subjectivity, and power. Deleuze and Guattari’s approach focuses on how cinema affords new concepts for creatively changing and challenging individual and social status. The schizoanalysis approach, first developed in Anti-Oedipus (1972) and later further enriched in A Thousand Plateaus (1980), explores how cinema produces new concepts and ways of thinking about the world and the creation of subjectivity in film and society.24Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (The University of Minnesota Press, 1987). In their analysis, cinema is not just a reflection of society but actively shapes people’s subjectivities. According to Deleuze and Guattari, subjectivity is not fixed; it is a process constantly in flux and shaped by the forces and power relations at play in society. They argue that the way in which films create subjectivity is not simply by representing it but by actively engaging with and shaping it.

Deleuze and Guattari first coin and discuss schizoanalysis in their book Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, exploring the intersection of psychoanalysis, capitalism, and social theory. They use schizoanalysis to describe their alternative approach to understanding the human psyche, challenging traditional psychoanalytic theories by emphasizing the productive and creative capacities of the unconscious, as well as the liberating potential of desire. They also argue for a revaluation of the traditional psychiatric understanding of schizophrenia and propose a new understanding of the schizo as a revolutionary figure.

For instance, in Freudian psychoanalysis, the ego is defined by its Oedipal relationship to “daddy-mommy.” For Deleuze and Guattari, “the schizo has long since ceased to believe in it . . . the Oedipal, neurotic one: daddy-mommy-me.”25Deleuze and Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, 23. Instead of seeing schizophrenia as a pathological condition, they view it as a creative and subversive force that challenges dominant modes of subjectivity and social organization, aiming to disrupt established power structures and create new modes of existence through “the process of the production of desire and desiring-machines.”26Deleuze and Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, 24. Following their ideas then, we are able to read Close-Up as an exploration of the relationship between Sabzīyān’s subjectivity and power and how he resists and subverts dominant power structures by adopting an identity with symbolic capital to do what he loves.

According to Deleuze and Guattari, the schizo represents a deterritorializing force that breaks free from fixed identities, established hierarchies, and repressive social structures. They explore the potential of schizoanalysis as a method of inquiry that embraces multiplicity, becoming, and the free flow of desire. Schizoanalysis seeks to liberate desire from the constraints of psychoanalysis and societal norms, aiming to unleash the transformative power of desire and challenge the oppressive mechanisms of capitalist societies. The schizo represents a form of subjectivity characterized by fluidity, deterritorialization, and the rejection of fixed identities. They propose that the schizo is not limited by societal norms and operates beyond the constraints of the Oedipal structure. The schizo is thus characterized by their ability to resist social norms and power structures and to create new forms of identity. Further, the schizo’s dissolution of boundaries between inside and outside —again, we might think of zāhir and bātin—and self and other, challenges the dominant system of meaning-making and classification which relies on fixed categories and hierarchies. Consequently, these becomings operate as subversive forces that can challenge and disrupt the existing social order. Thinking with Deleuze and Guattari’s conceptual frames, Close-Up blurs the lines between documentary and fiction in Iran’s political and cultural climate at the time of its production. In doing so, Kīyārustamī and Sabzīyān challenge the status quo by producing disruptive meanings, especially in the way that Sabzīyān engages with the compelling force of his desire for cinema as a means of empowerment.

For instance, the film displays the creation of Sabzīyān’s subjectivity which creates a new identity and which itself then becomes the film’s subject. The film’s portrayal of Sabzīyān’s subjectivity is not simply a representation of a pre-existing identity, but rather an active process of becoming; even when he responds to Kīyārustamī’s and the judge’s questions, we are not sure whether he is “acting” or “being” his true self. Meanwhile, Kīyārustamī’s hybrid cinéma vérité style creates a particular subjectivity through the interaction of real and fictional elements. Similarly, Sabzīyān’s subjectivity is displayed as a hybrid of the real and imagined. In addition, Close-Up can also be seen as a commentary on the power dynamics between individuals and the state and between different social classes in Iranian society. Overall, we as the audience come to witness the film’s focus on the role and power of storytelling as a way of challenging dominant power structures and hegemonic narratives, which thus creates new possibilities for subjectivity and narratives of the self and nation as well.

Arguably, Sabzīyān’s desire to be a filmmaker and his admiration for Makhmalbāf reflect his desire for recognition and creative self-expression. However, Sabzīyān’s attempts to gain power and recognition through deception and manipulation are far more interesting if we instead consider them to be expressions of his subjectivity shaped by the power dynamics within the hierarchies of Iranian society. Accordingly, Close-Up raises questions about the artist’s role and creative expression as forms of resistance and as tools against disciplining power.

In his 1996 essay, “Notes on Close-Up,” Jonathan Rosenbaum discusses the dynamics of social class in Iranian society. In particular, he notes how Close-Up is a film that “deals with issues of class and status in ways that are both subtle and complex.”27Jonathan Rosenbaum, “Notes on Close-Up,” in Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (The University of California Press, 1996), 165. Rosenbaum believes that Kīyārustamī’s examination of class is most evident in the courtroom scenes where the middle-class Āhankhāh family testifies against the behavior of Sabzīyān who belongs to a much lower class. Rosenbaum writes elsewhere that “the testimony reveals how class and status are intertwined in Iranian society and how these factors determine a person’s opportunities and behavior.”28Jonathan Rosenbaum, “Lessons from a Master” jonathanrosenbaum.net, January 5, 2022. Accessed 08/08/2023, https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/2022/01/lessons-from-a-master/ Overall, Rosenbaum considers Close-Up a powerful critique of the social and economic inequalities in Iran and a commentary on how these inequalities shape individuals’ behaviors and relationships.

Indeed, this interweaving of class and status and the limits of an individual’s access to the latter due to a lack of the former is evident throughout the film. However, Sabzīyān’s desire is not just for fame but also for the power and authority that comes with it—to the point of some rather hilarious admissions. For instance, his desire for authority is evidenced when he explains:

I liked it [impersonating Makhmalbāf] because I could ask them [the Āhankhāhs] to do whatever I asked them to do. If I asked them to move a heavy dresser, they would have; if I’d asked them to cut down a tree, they would have. Before, no one would ever have obeyed me like that because I’m just a poor man.29Close-Up, 00:45:05. However, Sabzīyān’s desires are ultimately frustrated by the social and economic constraints that prevent him from realizing his dreams. In this way, the film exposes how power and desire are intertwined in society. What is more, the film portrays Sabzīyān as a man marginalized and excluded from mainstream society who nevertheless attempts to subvert his status by telling stories and pretending to be a famous filmmaker. Amid the context of class, status, and power, it is even perhaps more interesting how Sabzīyān is not malicious by nature but is a deeply empathetic and sympathetic character with a genuine passion for cinema. He makes himself quite vulnerable by taking the risk of impersonating Makhmalbāf, and yet he is able to use his emotions and experiences gained through cinema to powerfully connect with the Āhankhāh family, albeit for only a short time. In the end, it is challenging to be unforgiving towards such an authentic cinephile who possesses such deep respect for the art of filmmaking.

Storytelling and Fabulation

While schizoanalysis and the “power of the false” provide us with productive avenues for exploring the impact and importance of the film concerning power and subjectivity, the way in which we receive the film’s narration is also relevant. That is, not only how we receive the story, but how the story is told to us. Indeed, storytelling plays a key role in exposing different aspects of Sabzīyān’s identity crisis, the symptoms of his imposter syndrome, and his transformation.

In his essay “Der Erzähler” (“The Storyteller,” 1936), the German philosopher and cultural critic Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) explains how storytelling was often part of oral tradition and that oral storytelling is based on personal experience between generations. Benjamin argues that modernity’s emphasis on individualism, efficiency, and rationality had caused the decline of oral storytellers and the rise of the written storyteller. Benjamin highlights the importance of the communal and personal nature of storytelling and how, as opposed to “information,” oral storytelling encourages “interpretation.” Specifically, Benjamin writes that “[p]ower lies in this freedom of interpretation, in the fact that the story does not simply impose meaning on the reader, but rather invites the reader to participate in the process of meaning-making.”30Walter Benjamin, “The Storyteller: Reflections on the Works of Nikolai Leskov.” in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken Books, 1999), 90. Through the cinéma vérité approach of the film, we come to see this collective, invitational power of freedom of interpretation. Not only do Sabzīyān and Kīyārustamī tell stories, but the audience is also cheerfully and self-reflexively asked to participate in and make their own interpretations of the incident being judged (interpreted) in court.

Meanwhile, Sabzīyān employs storytelling to maintain human connection and, more importantly, the audience’s empathy. Further, Kīyārustamī’s and Sabzīyān’s storytelling is not only a form of entertainment but also a means of communication, self-expression, and investigation. Indeed, throughout the film, various characters tell stories, whether it is Husayn Sabzīyān pretending to be Muhsin Makhmalbāf, or the family members recalling their encounters with Sabzīyān.

In these ways, Close-Up explores the storytelling power of cinema and how this power can shape our perceptions of reality. As someone deeply influenced by the stories he has seen in films, Sabzīyān understands his impersonation of Makhmalbāf as an opportunity for artistic performance and creative action. Close-Up depicts and evidences how the stories we tell ourselves and others can construct our identity and image which is usually (indeed, always) fragile and fluid. Sabzīyān takes up this opportunity for storytelling in order to create a respectable identity for himself that cheers up his existence, even if for only a short while. In Time and Narrative (1984), the French philosopher Paul Ricoeur (1913-2005) discusses the relationship between time, narrative, and identity, later arguing that storytelling is a way of “constructing a temporal identity.”31Paul Ricoeur, Time and Narrative, vol. 1, trans. Kathleen McLaughlin and David Pellauer (University of Chicago Press, 1984), 150. For Sabzīyān, his new identity as a famous filmmaker, however temporary, relies on his ability (that is, his power) for storytelling and the participation of the family he hoodwinks.

Figure 7: A still from Close-Up (1990), ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ep3595lzTJY (01:17:07).

As a marvelous example of cinéma vérité, Close-Up asks us, the audience, to consider how we ourselves may be performing or inhabiting different roles and identities in our own lives to escape alienation and achieve a sense of power and importance. On the other hand, Deleuze and Guattari believed with respect to cinema and literature that we are not meant to understand a character’s identity, whether real or imaginary. The transformation of the real character becomes important just when he starts imagining himself in a more privileged class. In this vein, Sabzīyān speaks about how his love and desire for cinema lead him to connect with others precisely through his passion for storytelling and filmmaking. Thus, Sabzīyān engages in the act of “fabulating” reality and his own life, constructing a fictional narrative that serves as the backdrop for Kīyārustamī’s film. This fabrication of fiction into reality creates an enchanting element within a world that feels disenchanted.

The term “fabulation” was first introduced by Deleuze and Guattari in their collaborative work, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (1980). Although they never discuss fabulation elaborately, it is a central concept in their approach to the politics and ethics of art that explores the relationship between storytelling, imagination, and subjective experience. For them, fabulation describes the creative process through which individuals construct narratives, invent characters, and engage in world-building activities. Deleuze makes it clear, however, that he prefers “fabulation” over “Utopia”: “Utopia is not a good concept: rather, there is a ‘fabulation’ common to the people and to art.”32Gilles Deleuze, Negotiations (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995), 174. In this way, fabulation indeed involves storytelling, but most significantly it involves the creation of a story and perhaps even forgery, as when the storyteller, like Kīyārustamī or Sabzīyān, deliberately blurs the lines between reality and fiction.

Thus, in Close-Up, both Kīyārustamī and Sabzīyān fabulate as they are entirely self-aware of their acts of storytelling. Sabzīyān does so to explore new domains of being; however, his passion for cinema blinds him, and we are only partially sure whether he is aware that he is challenging societal norms. Sabzīyān does this most powerfully for the sake of himself because the power of his (deceptive) imagination provides him with an escape from reality. Sabzīyān lies and performs someone else’s identity to transcend his sense of self and how he defines himself—someone with a greater sense of purpose and fulfillment that the economic and hierarchical machines of his society disallow him to attain.

Further, Sabzīyān is both a forger and an identity smuggler. On the one hand, he is a smuggler because, as an unknown, jobless, poor person who lives in the lower part of the city, he evades his own identity and forcefully fakes a new one (that of Makhmalbāf). That is, he smuggles Makhmalbāf’s identity into the Āhankhāh family home to hide his true identity. For the fake Sabzīyān, his true identity is worthless because no one gives him credit; therefore, he has to smuggle Makhmalbāf’s identity as the source of his real power in order to obtain prestige and respect. On the other hand, Sabzīyān smuggles a story, a fiction, a product of his imagination into his reality to give his life a compelling aspect and makes a modern legend out of it. The basis of Kīyārustamī’s film is both reality and Sabzīyān’s fiction, which is like smuggling a lie (an intruding imagination) into the reality of the Āhankhāh family’s life. What is important here is not who Sabzīyān is but rather his transformation into another person through impersonation.

Figure 8-11: Stills from Close-Up (1990), ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ep3595lzTJY (clockwise from top left: 01:22:52, 01:22:55, 01:22:58, 01:23:37).

If the alienated Gregor Samsa in Kafka’s The Metamorphosis wakes up one morning to find himself transformed into a giant bug, Sabzīyān, the alienated nobody in Tehran, enchants his identity into an artist through imaginative lies and storytelling. And if, as a result of his metamorphosis, Gregor was unable to work and became isolated from family and society, Sabzīyān’s schizo transformation from someone who already felt isolated into a copy of a well-known filmmaker provides him with the temporary opportunity to communicate enthusiastically with people around him. As a result, Sabzīyān temporarily perceives the world differently. Meanwhile, by making a film about Sabzīyān’s adventure, and especially the ending of Close-Up, Kīyārustamī himself demonstrates the redemptive power of cinema.

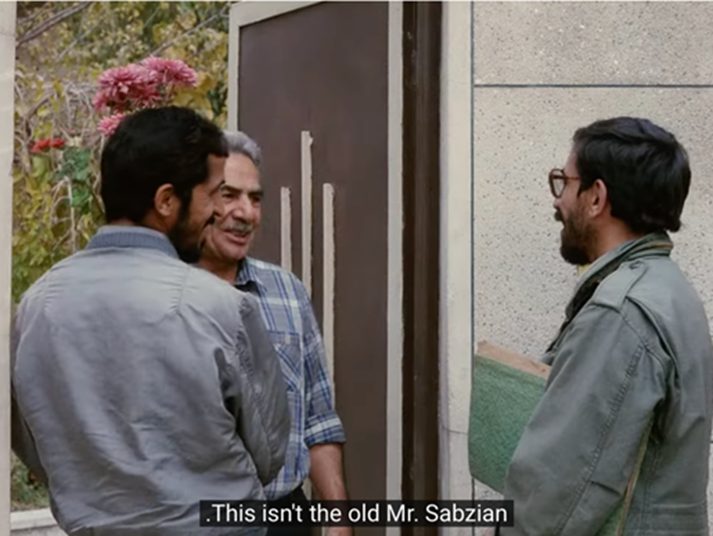

At the end of Close-Up, Husayn Sabzīyān has a sudden meeting with Muhsin Makhmalbāf—the copy meets the original—without any prior notice. Close-Up’s unparalleled ending summarizes what Kīyārustamī has presented to the world and reveals what the world of cinema has been all along: the paradoxical ease and restraint of creating an imaginary world, an improvisation, an accident, and the brilliance resulting from all of these. We witness reality and its (in)accurate recording as it happens in life—the coexistence of reality and fiction. When Sabzīyān sits on the passenger seat of Makhmalbāf’s motorcycle and asks for forgiveness, Makhmalbāf himself remarks that he is “tired of being Makhmalbāf,” as if to say that Sabzīyān/Makhmalbāf are two sides of the same fragile identity in the metropolis of Tehran, as pursued by Kīyārustamī in his favorite place, the car (see figures 13 & 14).33Close-Up, 01:37:56.

Figure 12 (left): A still from Close-Up (1990), ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ep3595lzTJY (01:29:31).

Figure 13 (right): A still from Close-Up (1990), ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ep3595lzTJY (01:30:21).

Figure 14 (left): A still from Close-Up (1990), ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ep3595lzTJY (01:31:26).

Figure 15 (right): A still from Close-Up (1990), ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ep3595lzTJY (01:34:01).

Figure 16: A still from Close-Up (1990), ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ep3595lzTJY (01:35:35).

In Conclusion: Cinéma Vérité and the Semi-Anthropological in Close-Up

Given this vivid and dynamic interplay of the false and the real throughout the film, it is interesting to note Close-Up’s semi-anthropological approach. Only after hearing the news of the prank and the arrest of Sabzīyān does Kīyārustamī plan to be directly involved in the process of Sabzīyān’s trial by making an observational and provocative film about the latter. Similar to the style of Jean Rouch, the leading French documentarian of cinéma vérité, Kīyārustamī’s interventions in the court, in addition to the question-and-answer session between the judge, Sabzīyān, and himself, make Close-Up a quasi-anthropological film—something that is equally characteristic of Kīyārustamī’s later film, Dah (Ten, 2002).34Jean Rouch was a French anthropologist and documentary filmmaker (1917-2004), considered by some to be the prophet of cinéma vérité. In the early 1960s, with the advancement of portable video and audio recording technology, it became possible for documentary filmmakers, especially ethnographic filmmakers, to use the relative freedom and convenience of portable cameras and audio recorders. With this technology, they could travel to various ethnic, minority, or other groups of interest during field research and, while engaging and living with them, record spontaneous and unpredictable events. The method went one step beyond the mere recording of events and, through questions and suggestions for discussion, stimulated the participants in the film to spontaneous cultural and ethnographic reactions. The documentary Chronique d’un été (Chronicle of a Summer; 1961) by Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin is an acclaimed example of cinema-vérité. The movement influenced French New Wave filmmakers such as Jean-Luc Godard. Further, in Close-Up, Kīyārustamī is not only a witness to the events, but in keeping with Rouch’s cinéma vérité style, he dialectically connects cinema and anthropology and blurs the border between reality and fantasy. In some moments of the film, especially in the court scenes and at the end, Kīyārustamī not only directs the film but also participates in the events or provokes them “directly” himself.

Figure 17: A still from Close-Up (1990), ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ep3595lzTJY (01:09:13).

Further, Kīyārustamī’s intervention during the court scene, where he assumes the role of interrogator and provocateur, transforms the film into an investigative narrative. This intervention unveils the concealed moral and psychological complexities within the sociocultural fabric of contemporary Iran. Through a series of gripping and enlightening dialogues revolving around themes of truth, falsehood, acting, and sincerity, Kīyārustamī engages in a profound exploration alongside the judge. Together, they inspect the intricate layers of these concepts, shedding light on the nuanced dynamics at play within Iranian society.

In these scenes, Kīyārustamī appears behind and in front of the camera and participates in the court’s discussion and questions so that he not only looks at Sabzīyān from a different perspective but, by engaging in this current, tragic situation, helps to improve Sabzīyān’s condition. As a “research film,” Close-Up echoes the larger image of Iranian society, its class divisions, and the challenges that the lower classes must undergo to attain decent self-estimation in the context of Iran in the 1980s, only a few years after the revolution and the eight-year war against Iraq.35Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema. Vol. 4, 204.

Overall, Kīyārustamī’s cinéma vérité approach in Close-Up not only represents reality but also verifies the latent truth by interfering with the subject through investigative interviews and conversations. In the fourth volume of A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Hamid Naficy discusses “the distinctions between direct cinema and cinéma vérité.” He explains that “cinéma vérité, particularly that practiced by trailblazers such as Jean Rouch, Jean-Luc Godard, and Errol Morris, intends to investigate reality by intervening and provoking it.”36Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema. Vol. 4, 202. Kīyārustamī’s diegetic presence in the film manifests through a series of recurring interrogations and suggestions directed towards Sabzīyān, thereby establishing a suitable framework for examining the intricate dynamics between individuals and the state within Iran. In this context, Sabzīyān’s character gradually unravels, revealing not only his underlying motivations and intricacies but also an all-consuming fixation on the world of cinema. These revelations serve as a poignant backdrop against which the oppressive influences of the forces of capital and the prevailing symbolic order are juxtaposed.

***

Husayn Sabzīyān suffered from asthma his entire life. He stopped breathing in the Tehran subway on June 5, 2006, his brain cells dying due to a lack of oxygen even before he was taken to Sīnā Hospital. He remained at the hospital in a coma for three months and twenty-four days until, on September 29, 2006, he died at the age of fifty-two. Sabzīyān was so poor that he could not afford to buy pain relief spray, let alone treat his disease. However, so rich was he in his love of cinema that he paid a hefty price to remain an immortal and iconic figure for those who lose themselves in the illusions of the silver screen.

Cite this article

This article analyzes Abbas Kiarostami’s Close-Up through the theoretical lens of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s notion of “the power of the false,” situating Sabzian’s performative identity within a broader philosophical framework that privileges interpretation over authenticity. The article further interrogates the film’s reliance on oral storytelling as a vehicle for shaping subjective realities and collective memory, emphasizing its significance in the sociocultural production of meaning in Iranian cinema.