“Drama” in Selected Iranian Cinema Posters: A study in Structuralist Narratology

Introduction

The history of movie posters is as old as cinema itself. A movie poster offers us a first glimpse into the world of film. For many viewers, the poster is their first encounter with a movie, and it is often this very image that sparks their interest in watching the film. Posters are essential elements in the movie marketing process, playing a crucial role not only in attracting an audience but also in embedding the film into their visual memory. What makes a movie poster attractive and memorable? How does the relationship between dramatic media (film) and visual media (poster) take shape? What differentiates a movie poster from other advertising posters? The answers to these questions lie in the concepts of “drama” and “narrative.” These two elements contribute to the overall appeal of the movie poster, forge a connection between film and poster, and distinguish movie posters from other forms of commercial visual culture. More than mere marketing tools, movie posters—when infused with narrative and dramatic cues—can extend the world of the film beyond the screen, creating a parallel visual narrative that shapes audience expectations, emotions, and memory.

In this article, I draw on Gérard Genette’s theory of narrative levels and Seymour Chatman’s model of the cinematic narrator to examine the narrative and dramatic structures of selected Iranian movie posters from the 1960s and 1970s. Iranian cinema went through a distinctive period during this time, in terms of style, ideology, and subject matter, encompassing both the commercial cinema known as fīlmfārsī and the more artistic tendencies of the Iranian New Wave. The diversity of form and content in the films of this period has also shaped the visual culture surrounding them, including poster design—a field often overlooked in Iranian cinema studies. By examining a broad selection of Iranian movie posters from these two decades and conducting close readings of selected examples, this article argues that posters from this era should be regarded as visual texts that actively contribute to the cinematic meaning-making process. Through their use of visual drama, character representation, genre cues, and narrative tension, these posters construct a parallel visual narration that not only promotes the film but also becomes part of its broader cultural memory. This analysis highlights the role of poster design as a semi-autonomous artistic and narrative practice within Iranian cinema history.

Movie Posters in Iran

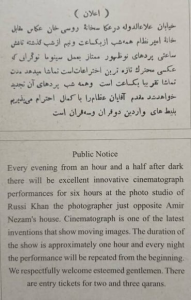

Movie (or film) posters have been used since the earliest public film exhibitions. Initially, they began as outside placards that listed the film program inside the hall or movie theater.1Charles Hiatt, Picture Posters: A Short History of the Illustrated Placard (G. Bell and Sons, 1895), 5. In the early 1900s, movie posters began to feature illustrations that captured scenes from the films. Some posters employed artistic interpretations of scenes or themes, represented through a wide variety of artistic styles. In Iran, the tradition of printing advertisements and notices to promote films began shortly after the first public exhibitions of foreign films. The first public screening of film in Iran took place in September 1904 by Mīrzā Ibrāhīm Sahhāfbāshī Tihrānī (1858–1921). Remarkably, this screening took place without any form of advertisement or public notice and was attended by a limited audience who had been invited. Three years later, in September 1907, Mahdī Īvānuf (also known as Rūsī Khān) initiated the public screening of film in his photography studio and published an advertisement in the second issue of the Habl al-Matīn newspaper to announce the public screening (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Advertisement for the first film exhibition in Iran, published in the second issue of Habl al-Matīn newspaper, September 1907.[mfn]Mas‛ūd Mihrābī, Sad sāl I‘lān va Pustir-i fīlm dar Īrān (Tehran: Nazar, 2011), 18.[/mfn]

The first movie notices in Iran did not advertise a specific film; instead, they announced the arrival of the cinematograph and promoted this emerging new art form.2Mas‛ūd Mihrābī, Sad sāl I‘lān va Pustir-i fīlm dar Īrān (Tehran: Nazar, 2011), 18-20. In the fall of 1909 movie titles were first used in the advertisements of Fārūs Cinema (established by Rūsī Khān), marking the birth of movie posters in Iran with this very advertisement.3Mas‛ūd Mihrābī, Sad sāl I‘lān va Pustir-i fīlm dar Īrān (Tehran: Nazar, 2011), 22. Interestingly, due to Rūsī Khān’s limited proficiency in Farsi, this advertisement has many spelling and writing errors. Furthermore, it highlights the major challenges of the movable type of that period – both in Farsi typesetting and in the gravure printing of a non-Iranian movie theater. The limitations of lead type in Persian, such as restricted character flexibility, difficulty in typesetting cursive and context-sensitive scripts, and the lack of typographic consistency, often led to poor-quality and error-prone printed texts. Movable type (a printing technology in which individual characters are cast on separate pieces of metal and assembled by hand) was especially problematic for the Persian script due to its connected and context-dependent letterforms (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The first use of movie titles in advertisements for Farūs Cinema, 1909.[mfn]Mas‛ūd Mihrābī, Sad sāl I‘lān va Pustir-i fīlm dar Īrān (Tehran: Nazar, 2011), 22 .[/mfn]

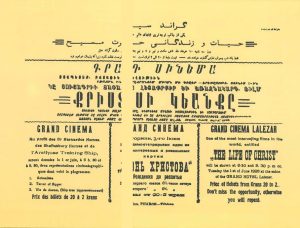

Since 1925, following the resumption of film screenings in Iran (which had been stopped since 1911 due to various reasons, including the Jungle Movement of Gīlān, the fall of the Qājār Dynasty, the First World War, and the 1917 Russian Revolution) lithographic and movable printed posters for foreign films gained popularity, now featuring illustrations from the film. Published in immigrant cities of Iran such as Tehran, Rasht, and Tabriz, these posters were often printed in three languages: Persian, Russian, and French, and sometimes Armenian and English. One interesting example of multilingualism in movie posters is found in the advertisement for the screening of the movie The Birth, the Life and the Death of Christ (Hayāt va Zindaganī-i Hazrat-i Masīh, 1906) at the Grand Cinema of Tehran in 1926. The poster of this film was presented in 5 languages (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Advertisement for the screening of The Birth, the Life, and the Death of Christ (Hayāt va Zindaganī-i Hazrat-i Masīh,1906) at the Grand Cinema of Tehran in 1926, possibly one of the rare movie posters in the world featuring information in five languages.[mfn]Mas‛ūd Mihrābī, Sad sāl I‘lān va Pustir-i fīlm dar Īrān (Tehran: Nazar, 2011), 31-32.[/mfn]

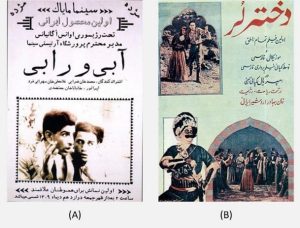

The poster of the first Iranian film, Ābī va Rābī (Abi and Rabi, 1930), directed by Uvānis Uhāniyān, does not exhibit a significant improvement in the design of movie posters compared to the past (Figure 4-A). Meanwhile, Khān Bahādur Ardashīr Īrānī, who made the first Iranian talkie film, Dukhtar-i Lur (The Lor Girl, 1933) made in India, sent a poster to Iran along with the film. This poster was designed by Chanda Warker, a graphic designer at Bombay’s Imperial Film Company (Figure 4-B). Although it was more sophisticated compared to common Iranian posters, it still looked amateurish in comparison with common American or European posters. Chanda Warker also designed some posters for the first few films of ‘Abd al-Husayn Sipantā, which were produced in India and had a significant impact on poster design of the first Iranian films.4Mas‛ūd Mihrābī, Sad sāl I‘lān va Pustir-i fīlm dar Īrān (Tehran: Nazar, 2011), 6.

Figure 4: (A) Poster for the first Iranian movie Ābī va Rābī (Abi and Rabi), directed by Uvānis Uhāniyān, 1930. Designer unknown; (B) Poster for the first Iranian talkie Dukhtar-i Lur (The Lor Girl), directed by Ardashīr Īrānī, 1933. Designed by Chanda Warker, graphic designer for Bombay’s Imperial Film Company.[mfn]Mas‛ūd Mihrābī, Sad sāl I‘lān va Pustir-i fīlm dar Īrān (Tehran: Nazar, 2011), 45, 47.[/mfn]

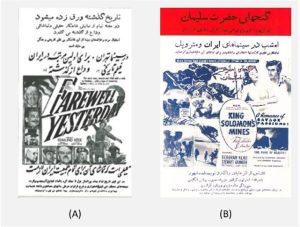

During the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran in 1941, film production temporarily halted in Iran. However, the release of non-Iranian films in Iran flourished, and the Persian posters for these films, which were usually collages of the original posters with Persian writings and paintings, were widely published in the press and periodicals (Figure 5). The widespread production of posters for foreign films indicates a single and definite style for film posters, which was used to prepare film posters after the resumption of filmmaking and the wide opening of cinemas in Tehran and other cities in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

Figure 5: (A) Persian poster for Farewell to Yesterday (Vidā‛ az Guzashtah, 1950). (B) Poster for King Solomon’s Mines (Ganj’hā-yi Hazrat-i Sulaymān, 1950), featuring a mixture of Farsi calligraphy and printed words added to the original poster.[mfn]Mas‛ūd Mihrābī, Sad sāl I‘lān va Pustir-i fīlm dar Īrān (Tehran: Nazar, 2011), 54, 55.[/mfn]

In the years leading up to the 1960s and 1970s, different styles were experimented with to create both commercial and non-commercial Iranian and non-Iranian movie posters. In the mid-1960s, Iranian cinema entered a distinct and passionate period. With the surge of filmmaking by a large number of commercial and non-commercial filmmakers during this period, Iranian cinema witnessed the emergence of some of its most prominent film poster designers, including Muhsin Davallū, Masʿūd Bihnām, Muhammad-ʿAlī Bātinī, Murtazā Kātūziyān, Muhammad-ʿAlī Hidat, Ahmad Masʿūdī, Farshīd Misqālī, Murtazā Mumayyiz, Qubād Shīvā, and many others.

Theoretical Framework

Structuralist narratology is a critical approach that emerged in the mid-20th century, primarily through the work of theorists like Roland Barthes, Gérard Genette, and Tzvetan Todorov. It seeks to analyze the underlying structures that govern narrative forms across media. To analyze the narrative and dramatic qualities of Iranian movie posters from the 1960s and 1970s, this article draws on key concepts from structuralist narratology. Specifically, I use Gérard Genette’s theory of narrative levels and Seymour Chatman’s model of cinematic narration as analytical tools. These frameworks enable us to understand how posters, despite being static visual artifacts, can participate in the multilayered act of storytelling—mirroring or extending the narrative structures of the films they promote. By applying these theories, I aim to demonstrate how certain posters evoke narrative cues, imply temporal sequences, and construct dramatic tension, thereby functioning as visual narratives in their own right.

Structuralist Narratology and Narrative Levels

Narratology, or narrative theory, is the study of narrative and its underlying structures as well as the ways in which they influence human perception. By examining the differences and similarities between the fundamental components of the narrative, narratologists seek to create a model that can be generalized for all types of narratives. Narratology, like any other branch of theoretical sciences, has seen many developments and periods whose theoretical lineage can be traced back to Aristotle. Modern narratology started with Russian formalists, and structuralism is one of its most important branches.

According to Genette, the narrative level constitutes one of three categories forming the narrating situation- the other two being “the time of narration” and “the person”.5Gérard Genette, Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method (Cornell UP, 1980), 228. Within the category of narrative level itself, Genette identifies three distinct layers that can coexist in a single narrative. These are: the level within the global text at which the telling of the narrator-character’s story occurs; the level at which the primary narrator’s discourse occurs; and the level of the narrative act situated outside the spatiotemporal coordinates of the primary narrator’s discourse. Narrative levels arranged bottom upwards, are extradiegetic (narrative act external to any diegesis), intradiegetic or diegetic (events presented in the primary narrative), and metadiegetic (narrative embedded within the intradiegetic level).

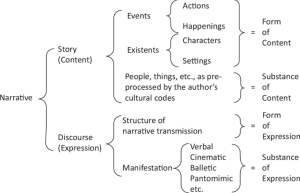

By drawing a strong boundary line between the narrative levels, Genette suggests that “transition between the narrative levels can only be done through the act of narrating… any other form of transfer is impossible, if not impossible, it will always be a kind of slippage from the principles of narration”.6Gérard Genette, Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method (Cornell UP, 1980), 234. With this definition, the connection between the narrator and the characters is impossible, and not only the narrator cannot communicate with the characters or interfere in the events of the story, but also the characters do not have access to the narrator and the extradiegetic level. As shown in Figure 6, Chatman also follows this leveling and uses the words “story” and “discourse” for the two main levels of narration. Structuralist narratology divides a narrative text into two parts: the story part, which includes the chain of events (actions and happenings) and existents (characters, settings) and the discourse through which the story is conveyed.

Figure 6: Seymour Chatman’s Elements of Narrative Theory.[mfn]Seymour Chatman, Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film (London: Cornell University Press, 1978), 26.[/mfn]

In other words, Chatman states that the story is the “content level” of the narrative while the discourse is its “expressive level”. The discourse determines which events should be narrated and which should not, whether they should be presented in chronological order or through reverse narration. It shapes the overall form of the narration.

Chatman further divides discourse into two components: “narrative Form” and “appearance in a specific materializing medium”.7Seymour Chatman, Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film (London: Cornell University Press, 1978), 22. Narrative form is the structure of narrative transmission and includes effects such as order, frequency, duration, narrator voice, and point of view. The material manifestation of discourse is the media through which the narrative becomes objectified, such as writing, film, ballet, and theater.

Interestingly, the story itself does not exist in an objective form; it is only accessible through the objective manifestations of discourse and the story is deduced from it. In fact, following Genette, discourse can be seen as the signifier and the story as the signified.8Gérard Genette, Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method (Cornell UP, 1980), 27. This makes it clear that if it is possible to extract the narrative form from the signs within a medium – as a result, extract the narrative discourse- even if that medium is not a narrative or dramatic medium, that medium has transformed into a narrative medium.

Cinematic Narrator

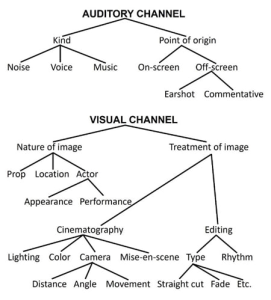

The cinematic narrator is the discourse agent who is in charge of the entire film’s narration. Chatman points out the extent of the narrative tools of the cinematic narrator and introduces these tools by dividing them into two visual and auditory channels.

Figure 7: Cinematic narrative tools in auditory and visual channel in films.[mfn]Seymour Chatman, Coming to terms: The Rhetoric of Narrative in Fiction and Film (Cornell University Press, 1990), 135.[/mfn]

As can be seen in Figure 7, all the elements that exist in a movie have a narrative function and a film conveys the story to us by putting aside different visual and audio tools and through its special discourse. It is important to remember that cinema is a dramatic art, and all these tools serve not only the narration but also the drama of the film.

The cinematic narrator presents events, characters, and story elements to the film’s audience using the tools and arrangements at its disposal. It does not interfere with the events and does not even see them. The cinematic narrator only conveys the story. It is a discursive agent: “a mechanism through which the story is presented.”9Seymour Chatman, Coming to terms: The Rhetoric of Narrative in Fiction and Film (Cornell University Press, 1990), 142. It can be said that the narrator presents the story through the images displayed on the screen (including set, actors, and other visual aids) and the sounds broadcast by the speaker (voices, music, and speech), and the audience infers its signifier (i.e., story) from the interpretation of this sign (discourse).

Towards a Methodology: Drama and Narrative in the Movie Poster

Based on the clarified theoretical framework—which draws on Gérard Genette’s concept of narrative levels and Seymour Chatman’s model of cinematic narration—a method can be proposed for analyzing dramatic elements in movie posters. In this approach, the film’s narrative discourse, conveyed through both visual and auditory elements, helps reconstruct the underlying story and its dramatic structure. Subsequently, this story can be re-examined at the level of the poster’s discourse, allowing for an analysis of how the poster presents or translates the drama of the film.

As shown in Figure 8, in this process, we analyze a dramatic story across two mediums: the film and the poster. Drawing on Gérard Genette’s theory of narrative levels and Seymour Chatman’s model of cinematic narration, I approach film and poster as two interrelated narrative systems. In Genette’s terms, the story (histoire) functions as the shared narrative level, while the discourse (discours) or the mode of presentation differs between the two. In the film, the discourse is constructed through cinematic signifiers such as actors, setting, camera movement, editing, music, and sound. In the poster, by contrast, the visual composition—including color, typography, image layout, character expressions, and background elements—serves its own kind of discourse, which may either reinforce or reshape the film’s narrative. Through this approach, I analyze how the poster draws upon or transforms narrative cues from the film to create a dramatic and memorable representation. This methodology allows us to evaluate movie posters not merely as advertising tools, but as condensed narrative artifacts that participate in the construction of meaning and memory for the viewer.

Figure 8: The method of analyzing the drama in movie posters, where the story becomes the common factor in both the movie and the poster’s discourses.

Drama in Selected Iranian Cinema Posters of the 1960s and 1970s

In my analysis of more than 300 movie posters from Iranian cinema during the 1960s and 1970s, I found that over 95% of these posters fall into the subcategory of “star-oriented” posters—where much of the composition is devoted to the image and name of the film stars. The remaining 5% employ a more minimal and iconographic approach to convey the film’s central concept. Notably, these exceptions were typically designed for non-commercial or art-house films, whereas fīlmfārsī productions consistently relied on star-oriented poster design.

By reviewing Iranian movie posters from the 1960s and 1970s, several recurring visual elements emerge. In most of these posters, the written components typically include the film’s title—often rendered in yellow—the names of the leading actors, production company details, and various credits. Alongside these textual features, a number of common non-written elements are frequently present: the prominent display of the film’s stars, images of dancing women or semi-nude women lying down (some of which depict scenes that do not actually appear in the film), and background illustrations that often depict action-oriented scenes such as fighting, horseback riding, dancing, and moments of flight or escape (Figure 9). These visual tropes are not incidental; rather, they reflect a set of stereotypical conventions—particularly gendered ones—used to attract audiences. The recurring depiction of hyper-feminized or sexualized female figures, for example, appeals to the male gaze and reinforces dominant commercial strategies of the time. It appears that poster designers often prioritized these sensational or formulaic elements to ensure the immediate attention of potential viewers. Only after fulfilling this initial function do they turn to more complex tasks, such as incorporating the film’s dramatic and narrative elements into the poster design. That said, not all posters are entirely devoid of drama. In several cases, the dramatic qualities of the film can be perceived through the facial expressions of the characters, the compositional arrangement of figures, and even the typographic treatment of the text—each contributing subtly to the evocation of conflict, emotion, and story.

Figure 9: Recurring elements in Iranian cinema posters from the 1960s and 1970s. (A) Tupulī (Chubby), directed by Rizā Mīrluhī, 1972. (B) Ātash-i Junūb (South Fire), directed by Alain Brunet, 1976. Designers are unknown.

Upon close examination of the Iranian commercial film posters from the 1960s and 1970s analyzed in this study—particularly those associated with the fīlmfārsī tradition— it becomes apparent that some elements of drama and narrative can be easily perceived in many of them. For example, in many of these posters, the movie genre can be easily perceived, especially in the comedy and action genres. Considering the same perception of the genre and the lack of variety in themes in commercial cinema and so-called fīlmfārsī, the theme of these works can be readily inferred. By observing these posters, even if we are not familiar with the movie stars of that period, the facial expressions and body gestures of the characters, as well as their composition, reveal the protagonist and antagonist to us. In many cases, these compositions also convey the relationships between the characters, especially if they are lovers or enemies. However, one of the most difficult narrative elements of drama, rarely seen in two-dimensional art such as posters, is the plot—an element that only a very small percentage of posters have managed to depict. In these posters, the designers show a part of the movie’s story to the viewer by representing dramatic action. Of course, it should be kept in mind that the movie poster is made to encourage the audience to see the movie and is not a completely independent art form. More importantly, designers should avoid attempting to convey the film’s entire story through the poster, as this medium is not intended to encapsulate the full narrative. In this context, we will examine the important elements of drama that can lead to the transfer of the narrative and plot in the poster, so that the various degrees of narration in the movie poster can be better understood.

Genre and theme

Genre is one of the central elements of dramatic storytelling and plays an essential role in attracting audiences in commercial cinema. Numerous studies in film marketing and audience research have shown that many viewers base their viewing decisions on genre familiarity and expectations.10Rick Altman, Film/Genre (BFI Publishing, 1999); Steve Neale, Genre and Hollywood (Routledge, 2000). The formation of genre-based fan communities—such as horror aficionados, action-film enthusiasts, or romantic comedy followers—demonstrates how genre not only guides audience preferences but also fosters shared identities and communities around specific cinematic styles and conventions. A genre is essentially a classification that groups thematic and story similarities in dramatic works. It comprises a set of conventions frequently repeated in certain films, categorizing them within a specific genre. In simple words, these conventions define what we are likely to see when watching movies of these genres. Each genre defines what events are acceptable and believable within its framework. The characters don’t suddenly start singing, except in a musical film, and in normal places, a crypt is usually not opened to the other world, except in horror or science-fiction films. Citing Gérard Genette, Jonathan Culler asserts that literature, like any other mental activity, relies on conventions that, except in certain cases, the mind remains unaware of.11Jonathan Culler, Structuralist Poetics: Structuralism, Linguistics, and the Study of Literature (Cornell University Press, 1975), 116. This insight is highly relevant to the analysis of film posters. Posters operate within a shared set of visual and narrative codes—regarding genre, character archetypes, color symbolism, composition, and typographic style—that guide the viewer’s understanding without requiring explicit instruction. These conventions, while often invisible to the audience, function as the scaffolding through which meaning is constructed. By applying this idea to film posters, we can see how certain visual elements resonate with culturally established narrative patterns and expectations, shaping viewers’ interpretations before they even watch the film. Therefore, analyzing a poster’s narrative and dramatic components means uncovering these hidden codes and understanding how they contribute to the poster’s ability to tell a story in a single glance.

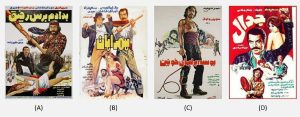

Genre cinema never became the mainstream of Iranian cinema; in fact, Iranian cinema is confined to local genres that blend several different genres. For example, the fīlmfārsī genre, reaching its peak of popularity in the 1960s and 1970s, is a combination of comedy-romantic and sometimes musical genres, with some fight scenes that are specific to the action genre or even the martial arts genre. But comedy and action genres hold a special appeal for Iranian audiences across several different periods, and some well-known films are made in these genres. Posters of Parvīz Sayyād’s comedy franchise with the famous character “Samad” introduce us to the concept of transferring the genre and theme of the movie into the movie poster (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Four posters from the Samad comedy franchise, directed by Parvīz Sayyād: (A) Samad bih Madrasah Mīravad (Samad Goes to the School, 1973). (B) Samad Ārtīst Mīshavad (Samad Becomes an Artist, 1974). (C) Samad Khushbakht Mīshavad (Samad Becomes Fortunate, 1975). (D) Samad dar Rāh-i Izhdahā (Samad in the Way of the Dragon, 1977).

In these posters, all the elements serve to convey genre and theme to the audience; the calligraphy of the title in all of these posters originates from the theme of the movies. The poster of Samad dar Rāh-i Izhdahā (Samad in the Way of the Dragon, 1977), which centers on Samad’s fascination with Bruce Lee’s martial arts films, the title is styled in a manner reminiscent of East Asian calligraphy (Figure 10-D), poster of Ṣamad Khushbakht Mīshavad (Samad Becomes Fortunate, 1975) which is about winning a lottery ticket, the title of the movie is similar to the margin of the newspapers of that period which was used to announce the winner or advertise the lottery (Figure 10-C), the title in poster of Samad bih Madrasah Mīravad (Samad Goes to the School, 1973), which deals with the theme of Samad’s education in adult schools, is similar to the chalk written on a blackboard (Figure 10-A), and in poster of Samad Ārtīst Mīshavad (Samad Becomes an Artist, 1974), which deals with Samad’s efforts to become an actor, the title is designed with the common font of Persian posters for foreign films (Figure 10-B). One of the elements used in these posters to transmit the genre (comedy) is parody. In the designs of many of these posters, you can see their humorous similarity to the poster of a serious movie. The pose of Samad’s character in the poster of Samad in the Way of the Dragon is a contrast to the poster of Bruce Lee’s movies, especially the poster of the Way of the Dragon (Figure 11-A). Similarly, the poster for Samad Becomes an Artist evokes the aesthetic of 1970s American and European action or spy film posters, particularly those of the James Bond series (Figure 11-B).

Figure 11: Posters of foreign movies used as parody sources for the Samad franchise posters: (A) French poster of Bruce Lee’s The Way of the Dragon (1972). (B) Italian poster of the first James Bond movie Dr. No (1962).

The Transmission of genre and theme in the posters of this series of films is not limited to these items, and many items in these posters have contributed to this. For example, the text on the posters of the two movies Samad goes to the school and Samad becomes an artist has made these posters comedic. The text on the poster of Samad becomes an artist introduces this film as “a historical and social film, a romantic and sexy film, an exceptional film, an art film, a karate film, a commercial and war film” and this exaggeration and contradiction have added an attractive comedic aspect to the poster. In the posters of Samad in the Way of the Dragon and Samad Becomes Fortunate, comedy elements such as the image of the dragon or the image of Samad while carrying his dreams have helped bring the genre and theme to these posters.

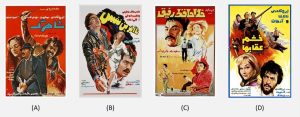

In addition to comedy films, movies in the crime and action genres have also made deliberate use of poster design to convey their genre and themes. A closer examination of these posters reveals that facial expressions and body gestures of the characters serve as key visual elements in constructing what can be called a thematic scene (Figure 12). By “thematic scene,” I refer to a condensed, emblematic representation of the film’s core emotional and narrative conflict — a moment that does not merely depict an event from the film but symbolically encapsulates its moral atmosphere and dramatic tension. For instance, in the poster for Bih Dādam Biras Rafīq (Help Me Friend, 1978) — a thriller dealing with prostitution and revenge — a woman’s blood-covered body dominates the foreground, while two male figures are positioned behind her with fearful facial expressions and gestures that suggest they are prepared for physical confrontation (Figure 12-A). This visual composition goes beyond mere representation; it evokes a sense of urgency, danger, and unresolved conflict that defines the film’s mood and storyline. Such gestures of readiness for violence, repeated across many posters of crime and action films, are not just aesthetic choices but meaningful signifiers. They communicate the central conflict and emotional intensity of the narrative. The spatial arrangement of figures and their expressions works together to construct a visual shorthand for the film’s world, effectively turning the poster into a narrative and thematic synopsis.

Figure 12: Posters of selected Iranian action and thriller movies from the 1970s: (A) Bih Dādam Biras Rafīq (Help Me, Friend), directed by Mahdī Fakhīmzādah, 1978. (B) Hamrāhān (Entourage), directed by Amīr Shirvān, 1977. (C) Būsah bar Lab’hā-yi Khūnīn (The Kiss on Bloody Lips), directed by Sāmū’il Khāchīkiyān, 1973. (D) Jidāl (The Controversy), directed by ‘Azīzallāh Bahādurī, 1976. Designers are unknown.

In addition to the facial expressions and gestures of the characters in some posters from the 1960s and 1970s, color and composition also play a significant role in conveying the genre and theme of the film (Figure 13). The use of a red background in the poster of the film Shāhreg (Artery, 1975), which deals with the theme of betrayal and friendship, and also the composition of this poster, which emphasizes a hand holding a knife, are elements that heighten the dramatic impact of this poster (Figure 13-A). The composition and color used in the posters of crime and action films of the 1960s and 1970s in Iranian cinema, besides defining the genre, sometimes also hint at the film’s theme.

In fact, the correct transfer of the genre through the poster is one of the first and main steps in the design of narrative posters. Genre is not only one of the important elements of drama, but it also plays an important role in directing the narrative path, and defining the genre in any artistic medium helps to understand the narrative framework of the story. If a poster designed for a comedy movie portrays a dry, cold, and serious atmosphere, subsequent efforts to create a narrative poster will go astray and lead to misimpression among the audience.

Figure 13: Posters of selected Iranian crime movies from the 1970s: (A) Shāhrag (Artery), directed by ‘Alīrizā Dāvūdnizhād, 1975. (B) Tā Ākharīn Nafas (To the Last Breath), directed by Kāmrān Qadakchiyān, 1978. (C) Khudāhāfiz Rafīq (Goodbye Friend), directed by Amīr Nādirī, 1971. (D) Khashm-i ‘Uqāb’hā (Wrath of Eagles), directed by Īraj Qādirī, 1970. Designer of (D) is Ahmad Masʿūdī; designers of other posters are unknown.

The majority of these posters (about 60%) introduce the genre and theme of the movie, generating anticipation among audiences interested in these genres and themes, who are eager to see these movies. If we consider genre and theme as the first components of the narrative discourse in cinema, noticed by the audience, their representation in the visual narrative discourse of the poster becomes crucial, serving as one of the audience’s first encounters with the film.

Characters and their Relationships

Character is one of the most important elements in the development of the plot and the story. It is the character that decides to act and moves the story forward and the plot is formed by the actions and reactions of the characters. As stated before, the facial expressions and gestures of the characters shown in the posters contribute to creating genre and conveying the theme in these posters. This section examines the representation of film characters in posters, focusing on which character traits are visually communicated and to what extent the relationships between characters are made apparent through poster composition.

Aristotle considers character to be the second essential element of drama after the plot. The actions of these characters drive the story, and in fact, the character serves as a driving force of the narrative. There are various types of characterization in drama, classified according to different criteria. Based on narrative importance, characters can be categorized as main, secondary, or auxiliary. From a functional perspective, we can distinguish between the protagonist or hero—who disrupts the status quo—and the antagonist or anti-hero—who obstructs the hero’s progress. Characters are also categorized by their individual traits: stock characters, who remain unchanged throughout the narrative; clichéd characters, who embody familiar and repetitive traits; and complex characters, who are distinctive, multidimensional, and evolve over the course of the story.

In the commercial films of Iranian cinema in the 1960s and 1970s, i.e. fīlmfārsī, the developed characterization is less common. In these movies, the characters emerge from familiar social types and remain within the bounds of stock character archetypes. The main characters in these films are brave, honorable, powerful, and often poor men who fall in love with a beautiful, witty, and usually wealthy young woman trapped by a corrupt, dishonorable, ugly, anti-hero, often the owner of a cabaret. The hero, after many struggles, accompanied by a friend or a disciple who makes the audience laugh with acrobatics and sometimes with a fake and exaggerated accent, achieves justice and wins the young woman heart as a prize. These hero and anti-hero characters are repeatedly performed by the same actors in some movies and become archetypes from conventional and stock characters, like the famous hero Mahdī Mishkī (Golden Heel), who has been portrayed in several movies by Nāsir Malik Mutī‛ī. These stereotypical characters were seen as a reliable formula for box office success. As shown in Figure 14, it was essential for the poster to clearly highlight the hero as a familiar and beloved figure—one whom audiences often emulated in dress or quoted in everyday life. This visual recognition played a key role in attracting viewers to the film.

Figure 14: Poster of fīlmfārsī movies featuring Mahdī Mishkī as the main character, portrayed by Nāsir Malik Mutī‛ī: (A) Ūstā Karīm, Nukaritīm (I Owe You One, Ousa Karim), directed by Mahmūd Kūshān 1974. (B) Āqā Mahdī Vārid Mīshavad (Here Comes Mr. Mehdi), directed by Farīdūn Zhūrak, 1975. (C) Mahdī Mishkī va Shalvārak-i Dāgh (Mehdi in Black and Hot Mini Pants), directed by Nizām Fātimī, 1972. (D) Pāshnah Talā (Golden Heel), directed by Nizām Fātimī, 1975.

In the movie posters featuring such characters, we see that the hero of the movie is illustrated with his usual heroic strength, next to his secretive friend and, of course, his beautiful lover. The repetition of these themes and characters eliminates the need to define the characters and their relationship in the film and poster because after seeing the actors together, the characters and relationships between them come alive for the audience. However, Iranian cinema in the 1960s and 1970s was not limited to these stereotyped characters. In both mainstream cinema and beyond, we occasionally come across characters with complex characteristics.

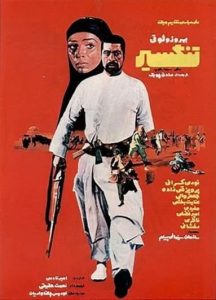

One of the most famous examples is Shīr Mammad, the hero of the 1973 movie Tangsīr, which is based on the novel Tangsīr by Sādiq Chūbak, itself inspired by real events. In this movie, we meet the simple, pure, and family-loving Zā’ir Muhammad Tangsīrī, who is fed up with the oppressive wealthy city elites who have borrowed and squandered his wealth and property. After bidding farewell to his wife and two children, he embarks on a path of revenge, not to recover the money but to protect his integrity, honor, and masculinity. The film portrays the transformation of Zā’ir Muhammad, a simple and calm man from Tangsīr, into the brave Shīr Mammad (Shīr means lion), one of the most iconic characters of Iranian cinema.

In this movie poster (Figure 15) features a simple composition set against a red background. Unlike typical posters of that period, the space in this poster is not fully occupied, and care has been taken to ensure that the text does not disrupt its sense of solitude. The main character of this film is illustrated in full length, walking forward with a gun in hand and a tired and angry face. All these elements have greatly contributed to the dramatic effect of the poster because the forward-moving gesture of Zā’ir Mammad suggests an impending incident. The emptiness and absence of any other character in the poster, except for the half-length image of Shīr Mammad’s wife, intensify the hero’s loneliness and helplessness. Other characters are only illustrated in a small size in the middle of the poster. In essence, this poster appropriately portrays the bravery and chivalry of the main character, and this characterization, which usually exists only in dramatic and narrative art mediums, is well presented in a fixed frame in this poster.

Figure 15: Poster of Tangsīr, directed by Nāsir Taqvā’ī, 1973. Designed by Ahmad Mas‛ūdī.[mfn]Mas‛ūd Mihrābī, Sad sāl I‘lān va Pustir-i fīlm dar Īrān (Tehran: Nazar, 2011), 118.[/mfn]

Character is a fundamental element of narrative, which is important at both the story and discourse levels. In the same way that techniques such as composition, costume and make-up, camera angle, acting, dialogue, and music are used for characterization in a cinematic narrative, techniques such as composition, gesture, color, and other graphic tools can also be used in a visual narrative for characterizing and representing movie characters and their relationships in the poster. Proper characterization in a movie poster becomes a significant step towards creating narration in the poster. In addition to introducing the hero or heroes, it plays an important role in clarifying the relationship between the characters and possible events in the story. Although narrative characterization in the visual arts seems to be a difficult task, examples such as the Tangsīr movie poster demonstrate the importance of this stage of movie poster design to create a narrative and dramatic poster. In fact, it is at the stage of character introduction that the cinematic narrative begins to transform into a graphic narrative. This is the point where the visual language of the poster takes on the task of translating the film’s narrative elements—previously expressed through motion, dialogue, or cinematography—into static yet meaningful visual symbols. Through visual cues such as facial expression, body language, color, and spatial composition, the poster must communicate who the characters are, what roles they play, and how they relate to one another. As such, the successful depiction of characters is not merely a design choice but a narrative strategy that bridges the gap between cinematic storytelling and visual communication in poster art.

Characters and their relationships are not always objectively represented in all the posters. In many cases, they are illustrated in allegorical, symbolic, or abstract forms. In such posters, the characters and the relationships between them are not fully conveyed to the audience, but the audience gets a complete understanding of them after watching the movie, and the questions that arise about the characters and their relationships after seeing the poster will be answered after watching the movie. Murtazā Mumayyiz, renowned for designing some of the most enduring posters of Iranian cinema in the 1970s, is one of the designers who usually employs this method in his movie poster designs (Figure 16). The poster of the movie Malakūt (The Divine One, 1976) abstractly depicts the relationship between the characters of Dr. Hātam and M.L. (Figure 16-A). Similarly, the relationship between the two brothers in the movie Ghazal (1976) is also depicted symbolically in the poster (Figure 16-E). In addition to Mumayyiz’s works, in the posters of Farshīd Misqālī for the movies Pustchī (The Postman, 1972) (Figure 17-A), Gāv (The Cow, 1969) (Figure 17-B), and Shāzdah Ihtijāb (Prince Ehtejab, 1974) (Figure 17-C), some of the posters designed by Muhammad-ʿAlī Hidat’s and Muhammad-ʿAlī Bātinī.

Figure 16: Movie posters designed by Murtazā Mumayyiz: (A) Malakūt (The Divine One), directed by Khusraw Harītāsh, 1976. (B) Mughul’hā (The Mongols), directed by Parvīz Kīmiyāvī, 1973. (C) Gavazn’hā (The Deers), directed by Mas‘ūd Kīmiyā’ī, 1974. (D) Balūch, directed by Mas‘ūd Kīmiyā’ī, 1972. (E) Ghazal, directed by Mas‘ūd Kīmiyā’ī, 1976.[mfn]Mas‛ūd Mihrābī, Sad sāl I‘lān va Pustir-i fīlm dar Īrān (Tehran: Nazar, 2011), 105, 116, 134, 141-42.[/mfn]

Examining movie posters from these two decades shows that the characterization and relationships between the characters are present in less than half of them (about 40%), and many of these posters have limited themselves to a simple image of the movie stars.

Figure 17: Movie posters designed by Farshīd Misqālī: (A) Pustchī (The Postman), directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī, 1972. (B) Gāv (The Cow), directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī, 1969. (C) Shāzdah Ihtijāb (Prince Ehtejab), directed by Bahman Farmānārā, 1974.

Plot and Dramatic Action

All elements of drama serve to create and convey the plot and story, which may explain why Aristotle considers the plot to be the most important element of tragedy.12Aristotle, Poetics, trans. Malcolm Heath (New York: Penguin Books, 1996), 12. In drama, plot is communicated to us through actions, where action represents the movement or development of plot and story in the dramatic arts. According to the theories of narrative levels and cinematic narrator, the different components of a film convey the story to us by making objective manifestations of the discourse. In a movie poster, an attempt is usually made not to reveal the whole plot but to depict a part of the dramatic action, so that in addition to making the poster dramatic, the story is prevented from being spoiled completely. In dramatic posters, by creating the main action, in addition to introducing the genre, theme, characters, and their relationships, a small part of the story is made visually. To design a dramatic poster that effectively represents a movie plot, it is necessary that the different components of the poster, from the texts, colors, and composition to the characters and the relationships between them, create action in the visual text of the poster.

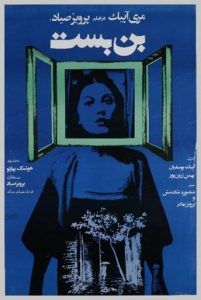

The main action of Bunbast (Dead End, 1977), based on a story by Anton Chekhov, is a girl watching a strange man through a window. In this film, a young girl who lives with her mother at the end of a dead-end alley looks out the window on a rainy day and notices a man is stalking their house. The man stands in the rain with an umbrella, looking at the girl’s window, and this scene repeats over the next few days. The poster for this movie (Figure 18) illustrates both the scene of the girl behind the window and the man with the umbrella. The image of the man is rendered in a monochromatic contrast of black and white, while the image of the girl features a monochromatic contrast of blue and black. The window frame employs a contrasting combination of green and black. Although this poster may appear calm and low-action at first glance, its tranquility actually stems from the film’s underlying drama. This film, which focuses primarily on the romantic fantasies of the girl character, is filled with images of her and her inner voice, weaving everything into a romantic fantasy. The film’s dreamlike atmosphere is heightened by Hūshang Bahārlū’s distinctive cinematography, the absence of a soundtrack, and the use of the girl’s internal monologue—most notably in a scene where a poem by the renowned Iranian poet Ahmad Shāmlū, recited in his own voice, deepens the sense of reverie. These romantic fantasies, however, are abruptly shattered in the film’s final moments. At the end, when the girl’s brother finally returns home from his travels, the unknown man enters and arrests the girl’s brother. Although this issue is not mentioned in this movie, the man behind the window is an agent of the Bureau for Intelligence and Security of the State (SAVAK), and the girl falls in love with him in her childhood fantasy.

Figure 18: Poster for Bunbast (Dead End), directed by Parvīz Sayyād, 1977. Designed by Murtazā Mumayyiz.[mfn]Mas‛ūd Mihrābī, Sad sāl I‘lān va Pustir-i fīlm dar Īrān (Tehran: Nazar, 2011), 145.[/mfn]

Unlike commercial films that often rely on controversy to attract attention, this poster reinforces the film’s dramatic essence and thoughtfully conveys its central narrative, without resorting to sensationalism. Just as everything in this film—made during the final year of the Pahlavī regime amid the turmoil of the 1979 Revolution—is symbolic, so too is everything symbolic in these posters. While watching this movie, we dream alongside the girl, but by the end, our beautiful imaginations and fantasies are shattered. This poster features a soothing blue background, likely inspired by the poem “Āy Ishq!” (Oh Love!), which includes the line “Your blue face cannot be found.” This poem, heard twice in the film, invites us into a dream, only for the stranger’s final words, “I’m sorry,” to wake us from this mistaken dream by the movie’s end.

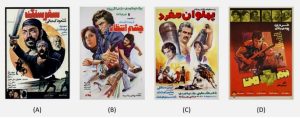

Although posters depicting multiple dramatic actions and various scenes from the movie may seem to convey a stronger sense of drama, closer examination reveals that the simultaneity of several narratives in the poster actually diminishes the power of the narration. As a result, they will be ignored and overshadow the drama in the poster. Figure 19 shows posters featuring several actions, and by examining them, it becomes clear that contrary to popular belief, these posters not only fail to convey drama and narration but may also cause confusion. For example, the placement of conflict scenes and numerous characters in the poster for ‛Alī Surchī (1972) (Figure 19-A) as well as the crowded and poorly composed layout of the poster for Tangah-yi Izhdahā (The Dragon’s Gorge, 1968) (Figure 19-D), illustrate attempts at storytelling that ultimately fail due to a lack of visual unity necessary for effective narrative expression. Moreover, in the posters of the films Jabbār, Sarjūkhah-yi Farārī (Jabbar, Runaway Sergeant, 1973) (Figure 19-C), and Gurg-i Bīzār (The Hateful Wolf, 1973) (Figure 19-B), it can be seen that the emphasized element in the poster, which is the face of the lead actors, is the least dramatic element of the poster, which reduces the power of the drama.

Figure 19: Selection of action film posters from the 1960s and 1970s (Part 1): (A) Alī Surchī, directed by Rizā Safāʾī, 1972; (B) Gurg-i Bīzār (The Hateful Wolf), directed by Māziyār Partaw, 1973. Designed by Muhammad-ʿAlī Hidat; (C) Jabbār, Sarjūkhah-yi Farārī (Jabbar, Runaway Sergeant), directed by Amān Mantiqī, 1973; (D) Tangah-yi Izhdahā (The Dragon’s Gorge), directed by Siyāmak Yāsamī, 1968.[mfn]Mas‛ūd Mihrābī, Sad sāl I‘lān va Pustir-i fīlm dar Īrān (Tehran: Nazar, 2011), 121.[/mfn]

Of course, there are also suitable dramatic examples of multi-action posters that have been able to serve the narrative of the poster through appropriate composition, creating focus on its most dramatic element, or by directing the audience’s eyes to multiple actions and dramatizing the poster amid its commotion (Figure 20). The poster of the movie Safar-i Sang (Journey of the Stone, 1978), designed by Muhammad-ʿAlī Bātinī, is an example of this kind of poster where the actors’ facial expressions and bodies are emphasized in a dramatic state, and the other actions depicted in the poster further enhance the power of the poster’s dramatic impact (Figure 20-A).

Figure 20: Selection of action film posters from the 1960s and 1970s (Part 2): (A) Safar-i Sang (Journey of the Stone), directed by Masʿūd Kīmiyāʾī, 1978. Designed by Muhammad-ʿAlī Bātinī; (B) Chashm Intizār (Awaiting), directed by Farīdūn Zhūrak, 1975; (C) Pahlivān Mufrad (The Hero Mofrad), directed by Amān Mantiqī, 1971; (D) Jahannam + man (Hell + Me), directed by Muhammad-ʿAlī Fardīn, 1972.[mfn]Mas‛ūd Mihrābī, Sad sāl I‘lān va Pustir-i fīlm dar Īrān (Tehran: Nazar, 2011), 148.[/mfn]

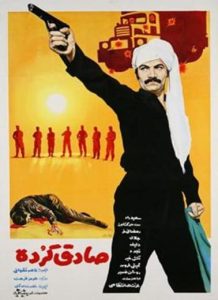

The most powerful movie posters in terms of drama and narrative – as opposed to design aesthetics – are those that directly confront the audience with the core dramatic action. By creating focus and emphasis on the most important action of the film, these posters drew viewers into the heart of the conflict; encountering such posters was equivalent to witnessing one of the film’s most pivotal scenes. An exemplary instance of such a dramatic poster is for the 1972 movie Sādiq Kurdah (Sadegh the Kurd) (Figure 21), directed by Nāsir Taqvā’ī. In this poster we are directly confronted by a character who is wielding his gun with authority and anger, leaving the audience seemingly with no way to escape. While creating curiosity, the other elements of the poster carefully compliment rather than distract from the main character. The sunny background, combined with the way the gun breaks through the frame—perhaps symbolizing a breach of legal or moral boundaries—heightens our curiosity about the film’s underlying lawlessness. A bullet-riddled truck—likely the work of the hero—along with shadowy figures who appear to be the story’s antagonists, and a man lying in a pool of his own blood at the hero’s feet, all serve as visual clues, hinting at a violent confrontation and suggesting the tragic arc of the hero’s journey.

Figure 21: Poster of Sādiq Kurdah (Sadegh the Kurd), directed by Nāsir Taqvā’ī and designed by Bihishtī, 1972.[mfn]Mas‛ūd Mihrābī, Sad sāl I‘lān va Pustir-i fīlm dar Īrān (Tehran: Nazar, 2011), 112.[/mfn]

The poster for Sādiq Kurdah not only raises many questions but also aligns with the film’s drama and story, providing substantial information without contradiction. Watching the movie leaves the same actions imprinted in our minds, as if the poster has presented a visual summary of the plot. The protagonist of this movie is Sādiq, known as “Sādiq the Kurd,” who runs a teahouse with his wife along the road from Andīmishk to Ahvāz. One night, in Sādiq’s absence, one of his friends, who is a truck driver, comes to the teahouse and, after raping Sādiq’s wife, kills her. Sergeant Valī Khan, Sādiq’s father-in-law, tries to arrest the murderer, while Sādiq seeks revenge by killing truck drivers. When Sergeant Valī Khan is assigned by the head of police to handle the case of the drivers’ murderer, he remains silent upon realizing that the killer is none other than his son-in-law. The head of police pressures Valī Khan, and on the day Sādiq plans to visit his house to see his son and borrow money to flee the country, he is surrounded by gendarmes and killed.

By examining this poster, one can see that through a cohesive visual unity—where all elements are drawn from the drama and story—the poster shapes the film’s drama and transforms its narrative from cinematic discourse into visual discourse. By removing details and non-dramatic elements, this poster introduces the audience not only to the genre and theme but also to the characters, going further to assume the role of narrator.

Posters with strong drama are very rare among the reviewed posters (less than 5%). Even posters containing action are usually weak in creating a cohesive plot and story due to the large number of illustrated actions. The poster of the movie Barādar-kushī (Fratricide, 1978) (Figure 22) directed by Īraj Qādirī is also one of the one-act posters that illustrate the drama in the most concise way possible, and this makes it powerful. This film is a story of forbidden love between a girl and a boy from two families that have held grudges against each other for years. The main character of this movie is Ghulām, the lover’s brother, who intends to end the old grudge between these two families by supporting the young lovers. In this poster, by removing secondary actions and additional details, the audience is placed in the middle of the conflict of the film and comes face-to-face with the main character of the film.

Figure 22: Poster of Barādar-kushī (Fratricide), directed by Īraj Qādirī and designed by B.N, 1978.[mfn]Mas‛ūd Mihrābī, Sad sāl I‘lān va Pustir-i fīlm dar Īrān (Tehran: Nazar, 2011), 157.[/mfn]

|

Total Posters |

Posters representing the genre or theme |

Posters representing characters |

Posters representing dramatic action |

Dramatic Posters (Genre, Theme, Characters, Action and Plot) |

|

307 |

260 |

117 |

97 |

12 |

|

percentage |

84 |

38 |

31 |

4 |

Conclusion

This research, aimed at exploring drama in Iranian cinema posters from the 1960s and 1970s, reveals that by applying the theory of narrative levels, narrative structures can also be identified in non-narrative and non-dramatic art forms. By incorporating the concept of cinematic narration into my analysis, I was able to establish a connection between the two mediums—film and poster—and explore the presence of drama within both. Through this method, the cinematic tools in the film medium convey both the story and drama to the audience. Next, based on the film’s story, the poster is analyzed to determine how the narrative and drama are represented within its visual discourse, and through which techniques this representation is achieved.

Based on the findings of this research, it can be stated that the drama in Iranian cinema posters from the 1960s and 1970s manifests itself on three distinct levels: At the first level, the genre and theme of the movie are represented in the poster; at the second level, the characters and their relationships are displayed; and at the final level, the plot of the drama is conveyed to the audience through the representation of dramatic action. There are examples of movie posters that, by effectively depicting the film’s central action, encapsulate the drama in a compelling way and explicitly convey elements of the story to the audience. By understanding the different levels of drama in these posters, cinema and theater poster designers can create compelling works that stand out from other types and effectively integrate both drama and narrative. To design an effective movie poster, one must first identify the various elements of the cinematic narrative discourse and then use the graphic tools of the poster medium to reconstruct these elements within a visual discourse.

Cite this article

Despite the rise of digital media, film posters continue to be a key medium for conveying a movie’s narrative, emotional tone, and genre. Beyond mere aesthetics or celebrity appeal, posters serve as the first dramatic and narrative expression of a film. This article explores how dramatic structures appear in Iranian movie posters from the 1960s and 1970s, applying Gérard Genette’s theory of narrative levels and Seymour Chatman’s model of the cinematic narrator. By comparing the narrative discourse of selected films with their posters, the study proposes a methodology for reading posters as parallel narrative texts. The findings demonstrate that dramatic content in posters emerges on three levels: genre and theme, character and relationships, and, finally, plot through visualized dramatic action. This approach reveals how cinematic and graphic media intersect in the construction of meaning, offering practical insights for analyzing and designing narrative-driven film posters.