Travelers (1991)

Musāfirān (Travelers, 1991)

“Travelers is a film about fertility, which may be what all my films are about: creation, fertility, and rebirth.”1Nooshabeh Amiri, Jedāl Bā Jahl [Fight Against Ignorance: A Conversation with Bahrām Bayzāʼī] (Tehran: Sālis Publication, 2013), 95. This and other quotations from the film and Bayzāʼī’s interviews with Zavon Ghokasian, published in Ghokasian’s book Darbārah-i musāfirān (About Travelers, 1992), are translated by the author unless otherwise noted.

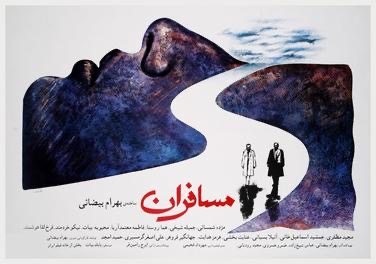

Figure 1: Poster for the film Musāfirān (Travelers, 1991). Poster designed by Ali Khosravi

Mahtāb, with her husband and two young sons, travels from northern Iran to Tehran in a rented car to bring the Dāvarān family’s heirloom mirror to her younger sister Māhrukh’s wedding. On their way, Zarrīn-kulāh, a village woman, joins them. Less than four minutes into the film, Mahtāb directly addresses the audience: “We’re going to Tehran for my younger sister’s wedding. We won’t get to Tehran. We’ll all die” (00:3:35).2All the images employed in this text are screenshots (under fair use) taken from different moments throughout the film on YouTube. All the rights of these visual elements belong exclusively to the film’s owner/creator/producer. Bahrām Bayzāʼī, Musāfirān (Travelers), 1991, YouTube, November 20, 2018, accessed 02/21/2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PCAUArjuGto&t=1732s

Figure 2: Mahtāb directly addressing the audience that they will all die in a car accident. Musāfirān (Travelers, 1991). Bahrām Bayzāʼī (00:3:35)

A few minutes later, they all do indeed perish in an accident with an oil tanker truck. When the news reaches the family, in a house that has been renovated and painted in preparation for the wedding, white curtains are replaced with black ones. While nearly all of the family members have accepted the death of the travelers, the grandmother (Khānum Buzurg) does not give up hope in mourning and refuses to believe that her daughter and family are dead. Although the police reports confirm the accident and the death of the passengers, there is no sign of the antique mirror.

Figure 3 (left): The antique mirror that Mahtāb was to take with them to her sister’s wedding, inserted in the opening credits. Musāfirān (Travelers, 1991). Bahrām Bayzāʼī (00:01:35)

Figure 4 (right): A still from Musāfirān (Travelers, 1991). Bahrām Bayzāʼī (00:02:04)

Her hope seems delusional to others and the family members decide to hold the funeral. Along with the dead’s relatives, the tanker truck driver, his apprentice, and the officers participate. The grandmother still insists on her belief and waits for Mahtāb’s arrival. To the various and surprising reactions of those present, Mahtāb and the five other recently deceased suddenly arrive with Mahtāb holding the mirror in front of her. At that moment, the light in the mirror is reflected on everyone’s faces. Mahtāb hands over the mirror to Māhrukh, and the wedding begins.

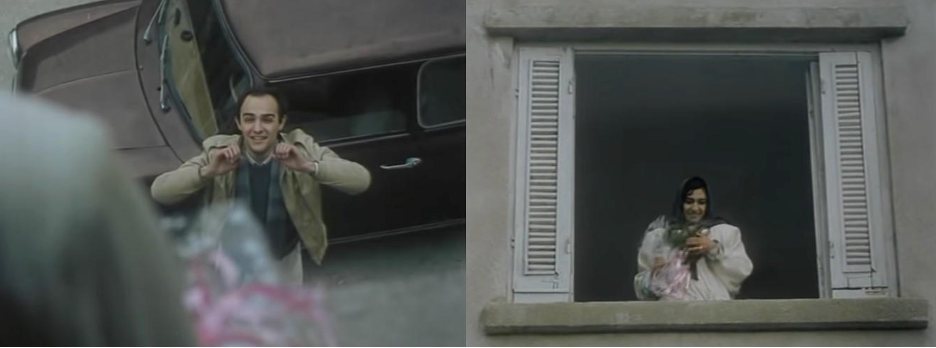

Figure 5-6: As the groom joyfully tosses a bouquet of vibrant flowers into the air which the bride happily takes, they eagerly share their excitement by exchanging heartfelt words, brimming with happiness, as they anticipate the arrival of the bride’s beloved sister and her family to their momentous wedding celebration. Musāfirān (Travelers, 1991). Bahrām Bayzāʼī (00:02:04)

Bahrām Bayzāʼī’s eighth film Musāfirān (Travelers, 1991) is a modern allegory of hope and rebirth drawn from the heart of helplessness. The film is also inspired by elements adopted from Iranian ritualistic passion plays (ta‛zīyah) and mystical ʻālam al-misāl, or what Henry Corbin (1930-1978) coined the “Imaginal World.” Bayzāʼī’s work can hardly be separated from mythology, and his engagement, interest, and expertise in mythology and rituals (as the hypothetical origin of the performing arts) is reflected in almost all of his creative and scholarly works.3See Bahrām Bayzāʼī, Namāyish dar Zhāpun (Theatre in Japan) (Tehran, Roshangaran Publication [1964] 2021); Namāyish dar Īrān (Theatre in Iran) (Tehran: Nashr-i Nivīsandah, 1965); Namāyish dar Chīn (Theatre in China) (Tehran: Roshangaran Publication, [1969] 2003). Of all such tropes, rebirth is the primordial inspiration for the constitution of a significant part of many human mythologies. In Travelers, Bayzāʼī elaborately engages with and appropriates not only myths of Rebirth but also of Death. The result, I argue, is the construction of a contemporary myth of rebirth that the grandmother and her wishful thinking symbolize in a situation darkened by the shadow of death.

Further, I argue that in Travelers, Bayzāʼī provides a version of a progressive gender politics in contemporary Iran. By using the film’s symbolic and mystical themes, he encourages this progressive gender politics which he has developed in almost all of his films and plays. Bayzāʼī’s treatment of female protagonists with strong, decisive, and independent personalities is evident in films such as Ragbār (Downpour, 1972), Gharībah va mih (The Stranger and the Fog, 1974), Kalāgh (The Crow, 1977), Chirīkah-yi Tārā (Ballad of Tara, 1979), Shāyad vaqt-i dı̄gar (Maybe Some Other Time, 1988), Bāshū: gharībah-yi kūchak (Bashu, the Little Stranger, 1989), Sag kushī (Killing Mad Dogs, 2001), Vaqtī hamah khvābīm (When We Are All Asleep, 2009) as well as scripts such as Haqāyiq darbārah-yi Laylā dukhtar-i Idrīs (Facts about Leila, the Daughter of Idris, 1975) and Shab-i samūr (Night of Sable, 1980).

In Travelers, the celebration of female characters is reflected in the young bride’s joyful presence and the life-affirming insights of the grandmother as an archetypal figure of hope and life. In a film culture in which the hero and savior is usually a male protagonist, it is notable that the main characters of Travelers are two women from two generations: Māhrukh (played by Muzhdah Shamsā’ī) and the grandmother (played by Jamīlah Shaykhī), who generate hope and life against death. The grandmother in particular symbolically addresses matriarchy’s life-saving insights. This theme, in turn, helps Bayzāʼī to structure his film both formally and conceptually.

For instance, the female characters in Travelers create the dramatic dynamism of the progression of the plot and subplots. At the beginning of Travelers, when her husband Hishmat (played by Hurmuz Hidāyat) worries about being late, Mahtāb (played by Humā Rūstā) offers a response that addresses Bayzāʼī’s alternative gender politics: “I am on time according to my watch. Does the world revolve around your watch?” (00:2:32). Similarly, the village woman who joins them to visit a doctor in Tehran is clearly independent, going against her husband’s will who suggested that she should not travel to the city. Thus, the representation of women in Bayzāʼī’s film challenges the conventional image constructed in most Iranian movies, especially mainstream movies of the time. Instead of censoring women and their affective presence, Bayzāʼī attempts to provide a dramatic context that reveals their empowered identity.

In an interview with Zavon Ghokasian, published in Ghokasian’s book Darbārah-i musāfirān (About Travelers, 1992), Bayzāʼī emphasizes the fact that even in Iranian traditional and patriarchal families, women frequently are the “center of the household” even though men “apparently” are seen as the ones who make decisions. Bayzāʼī further discusses how men’s decisions are guided by “an emotional way” that cannot be seen, and it is women’s art not to show this centrality. This centrality is invisible except when it is filmed.4Zavon Ghokasian, Darbārah-yi Musāfirān (On Travelers) (Roshangarān and Motaleat-e zanan Publication, 1992), 192. Furthermore, Bayzāʼī challenges patriarchy in the introduction to his book Namāyish dar Īrān (Performance in Iran, 1965) by claiming that “patriarchy” is equivalent to “despotism.”5Bahrām Bayzāʼī, Namāyish dar Īrān (Theatre in Iran) (The writer, and later Roshangaran Publication, 1965), 4.

Jamileh Sheykhi’s solemn yet powerful presence in her role as the grandmother adds to this powerful “centrality.” Her performance is a delicate and powerful portrayal that amplifies the conflicting emotions she feels and subsequently evokes in the audience. However, her presence also ignites a surge of self-empowering hope, nurtured by years of experience and resilience in the face of life’s trials and tribulations. On the other hand, she embodies more than just a motherly figure; she is a warrior, tirelessly striving to turn hope into reality despite the obstacles that occasionally drain her strength such as the moments when doubt creeps in, so intense that she staggers into her room, closes the door, and puts the photograph of Mahtāb and her grandchildren upside down (00:53:12). Similarly, after the burial, she finds herself standing alone in the falling snow, her heart heavy with sorrow and the weight of responsibility. She pleads silently to Mahtāb, urging her to appear, for without her presence, the life of “this kid”—Mahtāb—will be shattered (00:58:38). One may go further and argue that the grandmother is a contemporary rendering of Shahrzād (شهرزاد) from One Thousand and One Nights, who similarly defies death through her hope-inducing stories. Consequently, the grandmother can also be seen as a reference to the myth of creation, rebirth, and fertility set against death and infertility, which is embodied by the film’s theme and another character: Zarrīn-kulāh Subhānī, the village woman.

For instance, as Hikmat, the husband of Mahtāb’s other sister Hamdam, discusses the idea of demolishing the house to build new apartments, Khānum Buzurg, engrossed in her sewing, interjects, “Don’t talk about the destruction” (00:21:02; see Figure 7). And then later while every family member is impacted by the news of the death of Mahtāb and her family, the grandmother repeatedly says “She promised that the mirror will be here on time. She is on her way” (00:51:36). At times the grandmother even addresses the presence of the travelers despite the news of their death: “They died but didn’t finish” (01:06:11). Khānum Buzurg, a genuine embodiment of life-affirming wisdom, possesses the remarkable ability to perceive the intricacies of life’s challenges and transform them into a realm of unwavering hope. When sorrow and spiritual anguish permeate the family’s reality, Khānum Buzurg stands as a beacon of resilience and patience, breathing hope into the situation and reminding us that suffering can be overcome through holding on to and working towards hope.

Figure 7: Khānum Buzurg engrossed in her sewing, stopping Hekmat from talking about destruction. Musāfirān (Travelers, 1991). Bahrām Bayzāʼī (00:21:02)

Despite the harsh reality staring her in the face and the family members and guests offering their condolences to Khānum Buzurg, she adamantly clings to hope, employing the transformative power of “active imagination” (see below and footnote 6) to create a magical realm where Mahtāb and her family will undoubtedly attend the wedding.

Figure 8: After the burial, Khānum Buzurg pleads silently to Mahtāb, urging her to appear, for without her arrival, the life of “this kid” will be shattered. Musāfirān (Travelers, 1991). Bahrām Bayzāʼī (00:58:38)

Alongside these progressive gendered politics, in Travelers infertility is portrayed as a symbolic representation of death, effectively hindering the natural cycle of life. For instance, the theme of barrenness as death emerges through the character Zarrīn-kulāh Subhānī, the village woman, who accompanies Mahtāb’s family on their journey to Tehran specifically to seek medical treatment for her infertility. Tragically, Zarrīn-kulāh meets her demise in the car accident, thereby intensifying the motif of death in the narrative. Similarly, within the Dāvarān family, the other sister Hamdam (played by Mahbubah Bayāt), faces a daunting predicament. If she decides to conceive of carrying on the Dāvarān family lineage and name, she confronts a fifty percent chance of death.

Amid these various hauntings by death and infertility, the grandmother’s speculative, wishful, and self-fulfilling hope can be interpreted as what Henry Corbin (1997) coined the “active imagination”—a mystical faculty that brings ideas and thoughts to life. Although in Islamic mysticism, this vision can work as a mediator for understanding the image and presence of God through creating specific forms and images, Bayzāʼī subtly appropriates active imagination as a force that creates forms that address the very concept of “presence,” despite the material/physical absence of the recently deceased characters. Inspired by Ibn al-ʿArabī’s teachings, Corbin further writes: “The active imagination guides, anticipates, molds sense perception; that is why it transmutes sensory data into symbols (in the ‘ʻālam al-misāl’).”6Henry Corbin. Alone with the Alone: Creative Imagination in the Sufism of Ibn ‘Arabi (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1969), 80. In the realm of active imagination, the encounter between the invisible and the visible takes place.

Referring to the Persian Illuminationist philosopher Suhravardī’s (1154–1191) unique vocabulary, the scholar of mysticism Mehdi Amin-Razavi explains that according to him, this “imaginal domain” is seen as “the ontological origin of the corporeal world.” The imaginal forms that are suspended in the in-between world of the imaginal are not fixed entities like those in the world of Plato’s Ideas. The Sufi imaginal forms suspend between the material world and the spiritual world. Suhravardī identifies this “city of the soul” (shahristān-i jān) as the eighth domain (iqlīm-i hashtum). Corbin refers to this domain as mundus imaginalis or the Archetypal World and considers it to be a level of reality that has no external existence and yet is real; in fact, it is more real than the external world, the seemingly real. This real world therefore is the “imaginal” as opposed to “imaginary” which implies both non-real and non-existence.7Mehdi Amin Razavi, Suhrawardi and the School of Illumination (Surrey: Curzon Press, 1997), 87.

Notably, the ending of Travelers is inspired by mystical, archetypal forms of what Corbin termed the “Imaginal World” (‘ʻālam al-misāl,’ which has been mistranslated as an equivalent to Nā-kuj-Ābād, the “land of No-where”), forms that are the products of an “active-mystical imagination.” In this way, Bayzāʼī elaborately displays how the power of belief and hope can yield an affirmation of life vis-à-vis death. The ending materializes the imaginal generated by the mirror as a mediator between the two worlds: the real and the imagined. In a fascinating mise-en-scène, the mirror moves adjacent to the astonished and mourning participants, reflecting their images next to their true presence as if this imaginal world is a double of the real. Similarly, referencing ta‛zīyah in her book Displaced Allegories: Post-Revolutionary Iranian Cinema (2008), the Iranian-American scholar and film theorist Negar Mottahedeh relates the “imaginal (a word that combines image and original) . . . through which the articulation of national (identity) is desired.”8Negar Mottahedeh, Displaced Allegories: Post-Revolutionary Iranian Cinema (Durham NC: Duke University Press, 2008), 14; Mottahedeh considersʻālam al-misāl as “a timeless nowhere land (nā-kujā-ābād)” (14), which according to Corbin’s discussion of the term is not an appropriate equivalent. Corbin writes “Na-koja-Abad is a strange term. It does not occur in any Persian dictionary, and it was coined, as far as I know, by Sohravardi himself, from the resources of the purest Persian language. Literally, ( … ) , it signifies the city, the country or land (abad) of No-where (Na-koja) That is why we are here in the presence of a term that, at first sight, may appear to us as the exact equivalent of the term ou-topia, which, for its part, does not occur in the classical Greek dictionaries, and was coined by Thomas More as an abstract noun to designate the absence of any localization, of any given situs in a space that is discoverable and verifiable by the experience of our senses. Etymologically and literally, it would perhaps be exact to translate Na-koja-Abad by outopia, utopia, and yet with regard to the concept, the intention, and the true meaning, I believe that we would be guilty of mistranslation. It seems to me, therefore, that it is of fundamental importance to try, at least, to determine why this would be a mistranslation.” Corbin further explains thatʻālam al-misāl is s Spiritual Sphere, a visionary perception that is not a physical place, a where and “It is the ‘where’ that is in it. Or, rather, it is itself the ‘where’ of all things”; a spiritual sphere. See: Henri Corbin, “Mundus Imaginalis, or the Imaginary and the Imaginal,” Hermetic Library, retrieved 21/04/2023, https://hermetic.com/moorish/mundus-imaginalis

On the other hand, if we extend our interpretation, the ending can also attend to the second coming and reappearance of the Savior in Abrahamic religions. In his interview with Ghokasian while discussing the ending of Travelers, Bayzāʼī directly refers to the wish for the return of the dead from the underworld in Mesopotamian, Greek, and Christian mythologies: “Basically, every kind of thought of resurrection and coming alive after death is related to this wish.”9Zavon Ghokasian, Darbārah-yi Musāfirān (On Travelers) (Rushangarān Publication, 1992), 94.

Bayzāʼī’s skillful and contemporary treatment of motifs and archetypes of hope and life in Travelers ensured that it was a well-received and intellectually influential film of the period, even though it only relied on Iranian motifs without referencing any Western philosophies. Interestingly, even the so-called “Brechtian” instantiation technique at the beginning of Travelers originated in Islamicate ritualistic passion plays (ta‛zīyah) and other Eastern performance traditions such as those of Indian and Chinese ritualistic plays, long before the German poet and theatre theorist Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956) theorized and coined the technique.

Indeed, in the vast region of Iran and its neighboring areas, since approximately 700 BCE, a rich tapestry of ancient plays came to life in various forms with fertility as their original inspiration. Among these, ta‛zīyah, Islamicate passion plays, emerged as a timeless art. As a reimagined interpretation of these ancient plays, ta‛zīyah becomes a potent and evocative element in Bayzā’ī’s cinematic and theatrical creations.

In Travellers, Bayzā’ī ingeniously extracts ta‛zīyah from its traditional religious roots, transforming it into a captivating artistic expression within the realm of dramatic performance. These performances, whether they be fertility rituals or tragic and elegiac dramatic pieces like Sūg-i Sīyāvash (Mourning for Siavash) and ta‛zīyah commonly referred to as passion plays, leave an indelible mark on the hearts and minds of the audience. They stir deep emotions through their engaging performances and provoke profound thoughts through their self-reflexive and distancing style of performance and direction by addressing the fictionality of the events.

Zeroing in on these Iranian motifs, Hamid Naficy astutely discusses Bayzā’ī’s ta‛zīyah-inspired self-reflexivity and circular stage aesthetics in the making of Travelers:

As in taziyeh, the acting in the film is often declamatory, and some of the main characters being mourned are missing. The elaborate wedding ceremony in opulent circular hallways and a stairwell resembles a taziyeh in which guests, bride, and groom mourn the death of their loved ones in the accident. Circularity, an important principle of taziyeh staging, is emphasized not only by the film’s circular setting but also by the circular traveling of the camera as it covers the action and by the characters’ circular movements, particularly the bride as she spins around herself often.10Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema. Vol. 4, The Globalizing Era, 1984-2010 (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2012), 195-96.

Figure 9 (left): The ta‛zīyah aesthetics can be seen in the way the two drivers are surrounded by Mahtāb’s family members and the mourners. Musāfirān (Travelers, 1991). Bahrām Bayzāʼī (01:23:30)

Figure 10 (right): A still from Musāfirān (Travelers, 1991). Bahrām Bayzāʼī (01:25:51)

Such ta‛zīyah aesthetics are extended in the scene in which the relatives of Zarrīn-kulāh attack the driver and his assistant in the center of the hall. The driver’s wife Effat (played by Mahtāb Nasīrpūr) stands up and helplessly begs the attackers while holding her infant: “Please have mercy on this innocent infant” (01:22:04; see figure 11). This scene symbolically refers to similar scenes usually performed in ta‛zīyah which are reminiscent of the innocence of Imam Husayn’s son, ‛Alī Asghar, who was only six months old when martyred in Karbala.

Figure 11: Another symbolic reference to ta‛zīyah and the martyrdom of Imam Husayn’s son, ‛Alī Asghar in Karbala. Musāfirān (Travelers, 1991). Bahrām Bayzāʼī (01:22:04)

The unique rendition of ta‛zīyah by Bayzāʼī is mixed with Mihrdād Fakhīmī’s distinctive cinematography. Bayzāʼī’s directing style blends passion play traditions with cinematic realism. His distinct visual style presents a fictionalized version of reality that is impressionistic and at times expressionistic, reminiscent of the visually captivating scenes crafted by cinema by renowned modern European filmmakers like Andrei Tarkovsky (1932-1986), Krzysztof Kieślowski (1941-1996), Ingmar Bergman (1918-2007), and Federico Fellini (1920-1993).

The skillful use of meditative and intricately designed visuals in Travelers masterfully engages the audience, provoking introspection on questions about life, death, hope, and the essence of existence itself. In this way, his cinematic style serves as a catalyst for the audience’s contemplation through distancing performances that urge them to navigate the world without succumbing to sorrow, regret, or fear. In this fusion of ancient tradition and contemporary cinematic artistry, Bayzāʼī’s rendering of ta‛zīyah captivates the senses and stimulates the intellect—a testament to the enduring power of the performing arts to transcend time and cultural boundaries, leaving a lasting impact on those fortunate enough to witness its magic.

Through the build-up of all of these aesthetic and stylistic elements, Bayzāʼī’s account of the believability of the film’s final scene is worth mentioning:

No one needs to believe the final scene. It is enough to love it and sympathize with the desire hidden in it—which is an ancient human desire. The idea that even the dead advise us to live is more important than asking whether the dead would come alive.11Ghokasian, Darbārah-yi Musāfirān (On Travelers), 117.

. . . Many of us live with those we have lost, and they are present in our lives, even if they are not visible. Khānum Buzurg [the grandmother] displays that. It is easy to understand it, especially for a nation that lives with its past culture and its dead. In the final scene, they come and hand over the mirror. They come to praise life and celebrate it for the new generation.12Ghokasian, Darbārah-yi Musāfirān (On Travelers), 167.

Indeed, among all the symbolic elements in Travelers, the mirror has the most powerful implications of clarity, vitality, and, more importantly, the authentic historical identity of a nation—the archival memory of it—in addition to the abstract symbol of lucid mythological truth associated with life. “The mirror in Persian [āʼīnah] has the implication of āʼīn [rite]. In addition, āʼīn is a rite/custom with which an individual or a group of people identify.”13Omid Behbahani, “Vāzhah-i Sughdī-yi βδ¦en¦e va rābitah-i ān bā ā‛īn va ā‛īnah,” Nāmah-yi Farhangistān 6, no. 1 (2003), 189-90. As preparations for Mahtāb’s family’s arrival and the commencement of the wedding ceremony are underway, the grandmother takes a moment to reflect on the profound significance of the mirror within their family’s history:

Grandmother: “Mastān, you saw the mirror at your wedding ceremony. It was at the wedding ceremony of each of us several generations ago. Each of us gave it to the new bride in the subsequent marriage. It was lost at the last wedding. Mahtāb searched a lot until she found it. We agreed that she would keep it.” (00:22:33)

This intergenerational connection strengthens the ritualistic symbolism of the mirror at the beginning and the end of the film. After stating that the film has two structural textures—the documentary-like and the ritualistic one—Bayzāʼī argues that it is the “ritualistic level of Travelers that allows Mahtāb to speak through images . . . by bringing in the mirror at the end.”14Ghokasian, Darbārah-yi Musāfirān (On Travelers), 120.

Mirrors have significant embodied symbolism in several of Bayzāʼī’s films, such as Ragbār, Chirīkah-yi Tārā, and Shāyad vaqt-i dīgar. Bayzāʼī himself directly refers to the mirror in Travelers as “a symbol of everything good; light; purity; culture; hope; creativity; fertility; happiness and life. This special mirror is a sign of continuity and fortune in Ma‛ārifīs’ [the grandmother’s ancestral surname] household.”15Ghokasian, Darbārah-yi Musāfirān (On Travelers), 167. Most importantly, a mirror as a symbol of Iranian cultural values and identity can be seen in the grandmother’s concerns about finding the mirror after the spread of the news of the death of Mahtāb’s family in the car accident. She occasionally asks about the mirror and relates it to the characters’ lives. In this way, the grandmother’s denial of the news of their deaths is indelibly linked to the fact that the mirror is not found; therefore, the travelers must still be alive. As she asks:

Grandmother: “Have you found a mirror?”

Traffic officer: “Not at all.”

Grandmother: “Even a fragmented one?” (00:50:25).

The mirror also reflects the memory of the past that creates both hope and identity, which is echoed in both Mastān’s husband Māhū and the grandmother’s accounts:

Grandmother: “We are each other’s dream.” (00:24:04).

Maho: “They continue in us in the form of memories and their effects.” (01:03:41)

As can be clearly seen through the film itself and his reflections about it, Bayzāʼī considers the past and its legacy to be alive in the present. For him, the in-between world of the imaginal can be more authentic than the real world (which is always a copy of the imaginal). In other words, the authenticity of a memory of the past finds itself in the present and becomes an element of identity. An element that not only determines what the past was but also determines what the following generations will develop as a vision of the future. Further and in relation to the mirror itself, according to the Moein Online Farsi Dictionary “A’īnah-yi Bakht (the mirror of fortune), is a mirror that is placed in front of the bride at the wedding ceremony,” i.e., the bride sees the reflection of her happiness when she looks at herself in it.16Muhammad Mu‛īn, “ آیینه بخت [A’īnah-yi Bakht, the mirror of fortune],” Mu‛īn Farsi Dictionary Vajehyab. accessed 02/22/2023, https://www.vajehyab.com/moein/آیینة+بخت

In this way, it seems that an individual or a nation is nothing without an image to hold onto, which keeps its culture and legacy alive. In his seminal book, But’hā-yi zihnī va khātirah-i azalī (Idols of the Mind and Eternal Memories, 1977), the cultural theorist and philosopher Dariush Shayegan (1935-2018) considers the Persian Garden as the archetypal image of Iranian culture and anthropology. However, in Travelers, Bayzāʼī offers instead an image of the mirror that reflects speculative truth: reality is not but the reflection of what we think/make of it. Bayzāʼī draws for us here a contemporary myth of an enlightening hope from the depth of the Shiʿi mythology of mourning/martyrdom—a myth which has occupied the Iranian psyche for fourteen centuries.

Figure 12 (left): When Mahtāb arrives with the mirror, the light in the mirror is reflected on everyone’s faces. Musāfirān (Travelers, 1991). Bahrām Bayzāʼī (1:30:43)

Figure 13 (right): A still from Musāfirān (Travelers, 1991). Bahrām Bayzāʼī (01:32:12)

The grandmother’s insistence on finding the mirror as a sign that would have confirmed the car crash further highlights the mythic dimension of the mirror. Death is the lack of life, and the mirror is the reflection of a nation’s life, without which the nation’s culture and legacy will fade away. To be in time and sustain it in life, there must be a continuation, and the mirror carries a trace/continuation of the past/heritage for future generations. Finally, the bride takes the bouquet from the bridegroom and the image of the bride falls in the mirror (see figure 14). To which the grandmother exclaims, “They came! I told you they are on their way. She promised me. Happy wedding, dear girl!” (01:32:43).

Figure 14 (left): Mahtāb and the five other recently deceased suddenly arrive with Mahtāb holding the mirror in front. Musāfirān (Travelers, 1991). Bahrām Bayzāʼī (01:29:17)

Figure 15 (right): The bride takes the bouquet from the bridegroom and the image of the bride falls in the mirror. Musāfirān (Travelers, 1991), Bahrām Bayzāʼī (01:33:41)

Travelers is thus conceptually acted out between the two powerful images of the mirror: the mirror in the film’s opening scene, which reflects the real world outside (i.e., the car, the sky, and the sea complemented by the diegetic sound of seagulls and sea waves), while the mirror at the end illuminates what was still not in sight—the imaginal space made of material life and effervescent creation.

In addition to the dominant significance of the mirror in Musāfirān, the enigmatic theme of “twins” in Bayzāʼī’s film has been usually missed in film criticism. However, in Musāfirān, twins serve as a deliberate and significant element that explores the duality of life. Although we cannot ascertain it with absolute certainty, Mahtāb’s two sons’ and Hamdam’s two daughters’ identical outfits and playful demeanors strongly suggest that they might be twins. The use of twins in Travelers (see figures 16 & 17) is not mere coincidence as it also appears in his other film, Maybe Some Other Time (Original title: Shāyad Vaghtī Dīgar, 1988), too. The most accessible example of the symbolic representation of twins in cinema is Stanley Kubrick’s film The Shining (1980), in which the twin sisters, known as the Grady twins, are seen as ghostly and malevolent apparitions who haunt the hotel and lead the isolated writer to death at the end. Contrary to Kubrick’s depiction, the twins in Travelers symbolize a fleeting yet joyful and vibrant force that resonates with the film’s theme of life. Mahtāb, accompanied by her twin boys at the beginning and end of Travelers, in addition to Hamdam’s twin girls, highlight this vital significance in the narrative. At the end, Mahtāb and the other travelers appear with Mahtāb’s two sons who look like twins on either side of the mirror, perhaps suggesting a parallel existence and the intricate complexities of life’s identity, encompassing both positive affirmations and negative denials. This theme is encouraged by the fleeting appearance of Hamdam’s daughters who look like twins, too. While the twin sisters in The Shining serve as an evil symbol contributing to the film’s themes of madness, death, and the supernatural, the twins in Travelers are represented as the embodiment of life’s vitality, reinforcing the film’s themes of hope, fertility, and rejuvenation.

Figure 16 (left): Mahtāb’s twin boys. Musāfirān (Travelers, 1991). Bahrām Bayzāʼī (00:02:16)

Figure 17 (right): Hamdam’s twin girls. Musāfirān (Travelers, 1991), Bahrām Bayzāʼī (00:45:52)

In Travelers, the stunning visual aesthetics are not the only impressive aspect of the film. The musical sound effects, which are sometimes digenic, add another layer of effectiveness. For example, when Māhrukh playfully moves around the house, she creates her own tunes with her mouth, adding a playful and joyful atmosphere. The music composer Bābak Bayāt’s music imitates these joyful mouth tunes extending them to the rest of the film, especially the ending. However, in stark contrast, as the mournful and tragic scenes unfold from the news of the death of Mahtāb’s family, the sound effects take on a digenic quality, resonating with the raw emotions. The echoes of wood striking a rug or the eerie cawing of crows intertwine, intensifying and imbuing these moments with a touchingly vivid emotional palette.

In the context of a wider history, it is notable that Travelers was made three years after the Iran-Iraq War (September 1980 to August 1988). During this time, Iranian society was experiencing the post-traumatic effects of a devastating conflict and, as a result, was longing for hope and confidence to rise from a depressive situation immersed in mourning for thousands of casualties of war. Although Travelers won six awards at the Fajr International Film Festival (1991) and held the record of fourteen nominations, Bayzāʼī was not able to make his next film, Sag-kushī (Killing Mad Dogs), for ten years.

As an “A-list director” who was not usually obliged to send their films’ screenplays for prior approval by the Islamic Cultural authorities, Bayzā’ī was still challenged by the authorities for the making of Travelers when he submitted the completed film for an exhibition permit to the MCIG (Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance). MCIG asked him to cut certain joyful scenes which made him so disappointed that he wrote a complaint letter to the ministry. As Naficy explains, after “protracted negotiations” and the revisions Bayzā’ī made to the film, “the official public screening of Travelers was still delayed by three years.”17Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, 38.

It is (perhaps cynically) surprising that despite Bayzā’ī’s success and celebrated fame among intellectuals and educated circles in Iran, and despite the frequent success among viewers of whatever he produced whether films or theatrical plays, both the Pahlavi regime and the post-1979 Revolution Islamic government often caused him difficulties whenever he decided to produce his films or plays. It becomes even more ironic when we know that Bayzā’ī’s themes and the language of his works are authentically Iranian.

However, apart from the many obstacles against his creative and cultural activities, Iranian New Wave Cinema has been continually graced by Bayzā’ī’s films. An important intellectual and cultural figure with a singular vision underpinned by hard work, research, and unparalleled knowledge of mythology and ritual performances, Bayzāʼī’s name and works are tied to the use of purified and original language and authentic intellectualism that has always proved necessary during the upheavals of Iranian society and its unstable politics. In a film culture dominated by Fīlmfārsī (pre-1979 revolutionary Iranian films with low quality and poor, vulgar plots) on one side and neorealism on the other, Bayzā’ī dedicated his wit and intellectual inquiries to a particular formalism in filmmaking that often is informed by its subject matter—the question of women’s identity, their impact, and their empowerment in the course of their lives amid a dominantly patriarchal society. Bayzā’ī adopts Eastern techniques of visual storytelling and takes them to an exceptionally high level by internalizing them and deploying them in his cinematic craftsmanship—a style that has become his epic signature.

Bahrām Bayzā’ī (born in 1937 in Tehran) emigrated to the United States in 2010 and has taught at Stanford University as the Bita Daryabari Lecturer of Persian Studies. He currently teaches courses on Iranian theater and cinema at Stanford.

Cite this article

This article investigates Bahrām Bayzāʼī’s Travelers through the prism of Iranian ritual performance (taʿziyeh) and the Sufi-inflected metaphysics of the “Imaginal World.” It argues that the film constructs a contemporary myth of spiritual rebirth—embodied in the figure of the grandmother—through richly symbolic and mystically charged imagery. The study also foregrounds Bayzāʼī’s progressive engagement with gender politics, illustrating how his formal innovations advance a feminist critique embedded within mythopoeic structures.