Maybe Some Other Time (1988)

Introduction

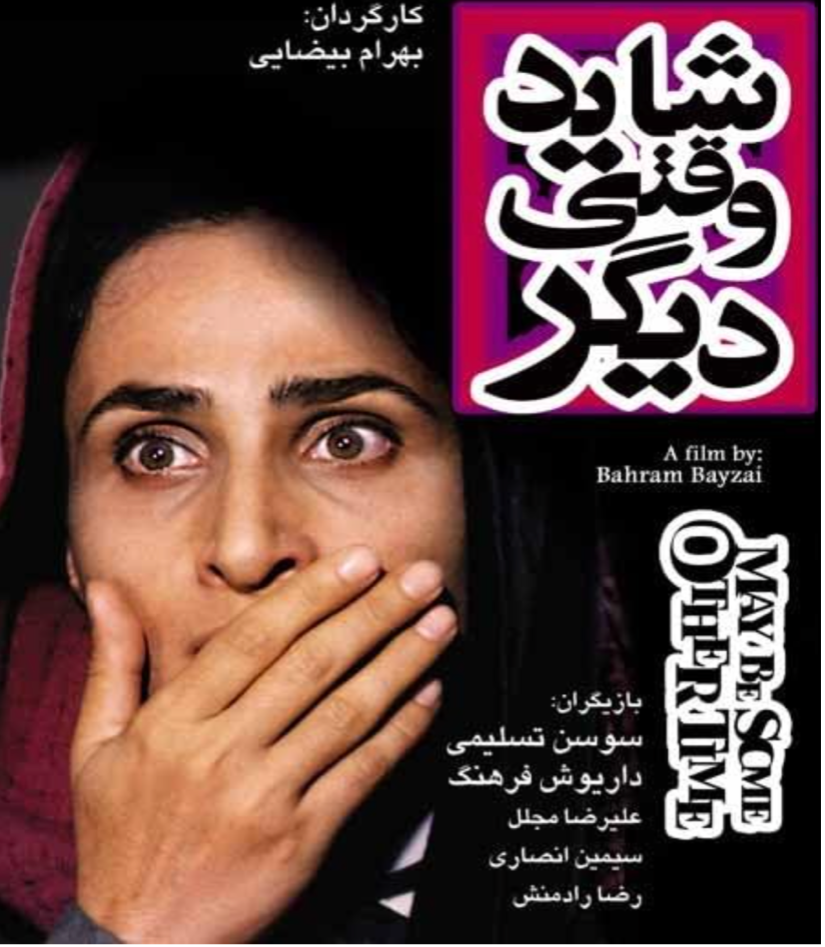

Maybe Some Other Time (Shāyad Vaqtī Dīgar, 1988)1All the images employed in this text are screenshots (under fair use) taken from different moments throughout the film on Namāshā. All the rights of these visual elements belong exclusively to the film’s owner/creator/producer. Shāyad Vaqtī Dīgar, directed by Bahrām Bayzāʼī (Namāshā, July 24, 2021), accessed July 3, 2023. https://www.namasha.com/v/dLYS3DdA/شاید_وقتی_دیگر displays the lives of Mudabbir and Kīyān, a middle-class couple residing in Tehran, Iran during the 1980s. The film was directed by Bahrām Bayzāʼī, one of the most prominent and highly influential filmmakers, playwrights, and writers associated with the Iranian New Wave.2Iranian New Wave Cinema that emerged in the 1960s and continued into the 1970s onward was a departure from traditional storytelling techniques and focused on social and political issues. The movement brought forth a new wave of talented filmmakers such as Hazhīr Dāryūsh, Bahrām Bayzāʼī, Nāsir Taghvā’ī, Furūgh Farrukhzād, Suhrāb Shāhid-Sālis, ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, Dāryūsh Mihrjūʽī, and others who challenged the conventions of Iranian cinema and in some cases gained international recognition. Bayzāʼī’s films often explore themes of identity, history, and cultural heritage, and he is known for his unique visual style, poetic storytelling and language, symbolism, innovative use of camera movements, and attention to details. Maybe Some Other Time is a fascinating example of the therapeutic exploration of the human psyche through cinematic enactments, particularly the role of the “mirror stage,” repression, dreams, and childhood experiences in shaping adult behavior. This article adopts Freudian and Lacanian approaches to understanding how Maybe Some Other Time explores Kīyān’s psychological repression, her mirror stage, her desire, and her formation of identity in relation to the symbolic order, as well as Mudabbir’s masculinity, male jealousy, vulnerability, and fear of castration. This article focuses on the ending of Bayzāʼī’s film and includes analysis of Gilles Deleuze’s notion of the camera eye. It then proceeds to explore the intricate connection between archives, the unconscious, and identity in the film.

Figure 1: Poster for the film Shāyad Vaqtī Dīgar (Maybe Some Other Time, 1988)

Although Bahrām Bayzāʼī is usually known for his use of powerful allegories with mythological themes in his films such as Charīkah-yi Tārā (Ballad of Tara, 1979) and Musāfirān (Travellers, 1990), Maybe Some Other Time is among Bayzāʼī’s less allegorical films which instead focus more on psychological investigations. The portrayal of a middle class Iranian urban couple in the 1980s seemed irrelevant at a time when Iranian cinema in international film festivals was known for its depiction of poor children characters and exotic rural settings in films such as Amir Naderi’s Davandah (The Runner, 1984), and ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī’s Khānah-yi Dūst Kujāst (Where Is the Friend’s House? 1987). More than two decades before the spread of social commentary films about middle-class families in Tehran such as Asghar Farhādī’s Oscar winning film A Separation (2011), Bahrām Bayzāʼī’s Maybe Some Other Time (1987) explores the complexities of a nuclear family living in Tehran during the 1980s.

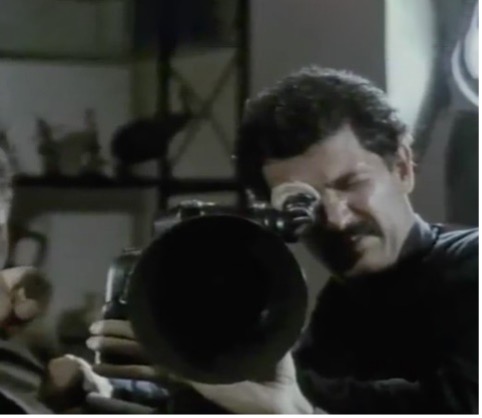

Maybe Some Other Time follows the story of Mudabbir, a television commentator working on a documentary about air pollution, who unexpectedly discovers his wife, Kīyān, engaging in a conversation with an unfamiliar man on the very footage he is dubbing (figures 1-2). This documentary footage casts Mudabbir into a turbulent emotional state, evoking feelings of jealousy, pride, and prejudice concerning his wife’s seemingly mysterious actions and subsequently his emotional feelings provoke a clash with his family’s moral values. The suspicion of Kīyān’s potential infidelity challenges Mudabbir’s understanding of reality, presenting him with a hypothetical scenario of Kīyān’s unfaithfulness that he must grapple with. Simultaneously, Kīyān, who has experienced a foster upbringing, is grappling with an identity crisis, intensified by her recent discovery of her pregnancy which contributes to her anxiety and unsettling dreams. To alleviate his doubts, Mudabbir, with the assistance of the documentary’s editor, locates the stranger from the footage, who is revealed to be Mr. Haq’nigar, an antiquarian with an extensive collection of historical artifacts in his cellar.

Intrigued, Mudabbir visits Mr. Haq’nigar’s antique store and unexpectedly comes across a portrait painting of Kīyān. This discovery prompts him to devise a plan to film a documentary on antique collecting at Mr. Haq’nigar’s house. His crew sets up at Haq’nigar’s house and checks their sound recording system. When Mudabbir sees that Haq’nigar’s wife, Vīdā, bears an exact resemblance to Kīyān, he calls Kīyān on the phone and asks her to join him at Mr. Haq’nigar’s address. As Kīyān knocks on Mr. Haq’nigar’s door, Mudabbir asks Vīdā to open the door. This unexpected meeting between sisters leads to a profound and distressing revelation for Kīyān, transporting her back to her childhood. She learns that their father passed away during their early years, and their mother, burdened by poverty, left Kīyān in the care of an anonymous family who rescued her from the street. This meeting with her sister contributed to Kīyān’s ongoing identity crisis and personal confusion. However, at the end of the film and upon leaving Haq’nigar’s house, Kīyān experiences a sense of relief, feeling that she has regained a sense of self.

The intricate storyline of Maybe Some Other Time explores the complexities of miscommunication and suspicion which could erode the desired trust and stability undergirding the Iranian middle class in the 1980s.

Figures 2-3: Mudabbir being shocked (Left) by seeing a woman resembling his wife Kīyān next to a male stranger in the footage he is dubbing (Right). Shāyad Vaqtī Dīgar (Maybe Some Other Time, 1988), Bahrām Bayzāʼī, (00:14:38)

Despite being a commissioned work, Bayzāʼī transformed the project into a remarkable film that explores the complicated journey of a woman in 1980s Tehran as she embarks on a quest to discover her true self. Bayzāʼī’s film seamlessly weaves together the alluring elements of the Noir genre, enveloping the audience in a world of suspense, suspicion, and enigmatic melodies where the Femme is not only fatal but also fatalized, adding depth to the characters and their struggles. The film mainly revolves around Kīyān, an Iranian woman who grapples with a complex psychological condition including an identity crisis, which is further intensified by disturbing feelings and dreams, all of which are triggered by the unsettling emotional consequences of obesity. Within this narrative framework, Kīyān also faces the challenges of marital pressures, particularly as her husband suspects her of infidelity. These suspicions exacerbate her existing identity crisis, creating a dynamic interplay between her personal struggles and the strains within her marriage. While Kīyān’s experiences serve as a focal point in the film, it is crucial to note that the narrative is equally propelled by Mudabbir’s suspicions and doubts regarding Kīyān’s faithfulness. Thus, both Kīyān and Mudabbir are equally important protagonists within the film’s narrative landscape.

Figure 4: Mudabbir talking on the phone at the dubbing studio where film images are projected onto a large background screen. Shāyad Vaqtī Dīgar (Maybe Some Other Time, 1988), Bahrām Bayzāʼī (00:07:44)

The film employs various cinematic techniques, such as flashbacks, surreal dream sequences, and film-within-film re-enactments that blur the line between reality and imagination, consciousness and unconsciousness, in the depth of Kīyān’s psychological struggles. (This is reminiscent of complicated psychological characters in films by cineastes such as Alfred Hitchcock’s Marnie [1964], Ingmar Bergman’s Persona [1966], Federico Fellini’s Juliet of the Spirits [1965], Andrei Tarkovsky’s Mirror [1975], Michelangelo Antonioni’s Identification of a Woman [1982], and David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive [2001]).

Repression

The concept of “repression” is addressed at the heart of the film through the delirious nightmares from which Kīyān suffers.3In her article “Bahram Bayzai’s Maybe…Some Other Time: The un-Present-able Iran,” Negar Mottahedeh explains that Bayzā’ī, in an interview with Sa‛īdah Pākravān from February 1995 in the journal Chantah, points out that the film directly addresses the question of identity (huvīyyat) and that, in fact, this is one aspect of Iranian life that had not been adequately explored in recent times. See: Negar Mottahedeh, “Bahram Bayzai’s Maybe…Some Other Time: The un-Present-able Iran.” Camera Obscura 15, no. 1 (May 1, 2000): 162. Her anxiety and delirious illusions (figure 5) reflect the workings of the unconscious mind, a central concept in Freudian theory. Furthermore, Kīyān’s vague memory of her past, her search for her identity, and her melancholic impressions affect her interactions with others, especially with her husband Mudabbir. Meanwhile, her inner turmoil is repeatedly triggered by Mudabbir’s suspicion-induced aggression and provocation through the use of cynical and bitter language which makes her suffer more throughout the film. In one of their family routines around the dinner table, Mudabbir loses his patience and verbally bullies Kīyān stating, “Life in these four-walled matchboxes must be very boring.”

Figure 5: One of the surreal and horrifying scenes that Kīyān envisions. Shāyad Vaqtī Dīgar (Maybe Some Other Time, 1988), Bahrām Bayzāʼī (01:45:40)

Later in the same scene, Mudabbir—believing he had seen Kīyān riding in a red car with an unknown man on the film he was editing—uses cynical language in an attempt to pry into what he erroneously imagines to be Kīyān’s secretive life:

Mudabbir: “If you were to have a car, what color would you wish it to be?”Kīyān: “What difference does it make?”Mudabbir: “So the difference is with the one who sits at the wheel?”4Maybe Some Other Time (00:28:25).

Mudabbir’s unintentional and spontaneous passive aggression and suspicion fuelled by strong moral taboos can be interpreted as symptomatic of his confrontation with his unconscious repressed anxieties, masculine vulnerability, fears, and insecurities.

According to Austrian psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic theory, dreams are the “royal road to the unconscious.”5Sigmund Freud, “The Interpretation of Dreams” in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, ed. James Strachey, vol. 4, (Hogarth Press, 1953), 608. In dreams, the unconsciousness talks with the individual in intimate yet different tones. The surreal and sweaty dream sequences in Maybe Some Other Time reflect Kīyān’s unconscious desire to know who she is and the anxieties caused by the absence of her birth parents’ attention and love.

The Freudian Oedipus complex is an essential aspect of Kīyān’s longing for her father. The void left by her father’s absence is an example of the Oedipus complex. According to Freud, in his seminal work The Interpretation of Dreams (1900), a child develops an unconscious desire for their opposite-sex parent and sees their same-sex parent as a rival.6Freud, “Interpretation of Dreams,” 274. Freud believed that resolving the complex is important for healthy adult sexuality.7We should note that the theory has faced criticism for its heteronormative and limited perspective. Mudabbir’s suspicion towards Kīyān reflects a fear of castration, which is a central aspect of the complex. Mudabbir’s desire to uncover the truth about Kīyān’s behavior derives from his jealousy about a rival to whom Mudabbir assumes he is losing Kīyān’s affection.

Figure 6: Kīyān and her foster parents in the background. Shāyad Vaqtī Dīgar (Maybe Some Other Time, 1988), Bahrām Bayzāʼī (00:05:24).

Figure 7: Photos of Kīyān’s foster parents in her photo album. Shāyad Vaqtī Dīgar (Maybe Some Other Time, 1988), Bahrām Bayzāʼī (00:19:00).

Mirror Stage

For the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, the unconscious is not merely a repository of repressed desires or traumatic experiences but a fundamental aspect of human subjectivity. According to Lacan, the formation of the subject’s identity is rooted in the mirror stage which fundamentally orients the subject within the symbolic order, a system of language and social norms that determines how individuals understand themselves and their place in society. Lacan believes that the mirror stage is a critical phase in the development of the human psyche through the formation of a self-coherent self:

[T]he mirror stage is a drama whose internal pressure pushes precipitously from insufficiency to anticipation—and, for the subject caught up in the lure of spatial identification, turns out fantasies that proceed from a fragmented image of the body to what I will call an “orthopedic” form of its totality—and to the finally donned armor of an alienating identity that will mark his entire mental development with its rigid structure.8Jacques Lacan, “The Mirror Stage as Formative of the I Function” in Écrits: A Selection, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Norton, 1977), 75-81, 78.

This stage usually occurs when an infant recognizes its reflection in a mirror, creating a sense of unity and coherence within her/his mind. The mirror stage is thus a critical moment in the formation of the ego, which Lacan sees as a necessary but ultimately illusory construct.9Lacan, “Mirror Stage,” 80.

Bayzāʼī’s fascination with mirrors and their mythological implications can be discerned in his earlier film, Ragbār (Downpour, 1972), all the way to his later works like Musāfirān (Travellers, 1991).10For more on the implications of mirrors in Bayzāʼī’s work, see Cinema Iranica’s entry for Bayzāʼī’s other film Musāfirān (Travellers, 1991). However, in Maybe Some Other Time, the mirror takes on a new significance, intertwining with the realm of cinema and psychology. Within the confines of their home, there is a mirror adorned with film perforations, serving as a visual motif (figure 8). At first, we see Kīyān on the phone in front of this mirror, and at another moment, she suddenly places her hand upon it after a heated dispute with Mudabbir. Maybe Some Other Time presents a unique conceptualization of the Lacanian mirror stage, exploring the depths of self-identity and perception.

Figure 8: Kīyān in front of the mirror with film perforations in the background. Shāyad Vaqtī Dīgar (Maybe Some Other Time, 1988), Bahrām Bayzāʼī (00:38:17).

Bayzāʼī further presents an intriguing exploration of Kīyān’s initial experience with the mirror stage within the setting of Haq’nigar’s antique store.11Maybe Some Other Time (01:59:53). It is through the surface of an artwork, specifically a painting (Vīdā’s portrait), that the revelation unfolds, impacting not only Kīyān but also, significantly, Mudabbir (figures 9-10). In Haq’nigar’s antique store, Kīyān’s eyes fell upon the portrait painting, an uncanny resemblance to Kīyān which unsettles her to the point of the feeling of suffocation and she flees from the antique store in a desperate frenzy. Later, in the climactic finale of the film where Kīyān first meets Vīdā, her long-lost twin sister, Kīyān comes to know the shocking truth that the haunting portrait actually belonged to Vīdā. Furthermore, Kīyān’s return to her childhood memories and her mother starts here from her recollection of the antique store which leads to her memories in Tehran, a revealing and cathartic episode that ends with healing and self-realization.

Figures 9-10: Kīyān visiting Haq’nigar’s antique store when she first sees a portrait that resembles herself which disturbs her to the point that she desperately runs outside the store. Shāyad Vaqtī Dīgar (Maybe Some Other Time, 1988), Bahrām Bayzāʼī (01:59:53).

Kīyān’s interaction with her twin sister Vīdā in the final scene emerges as an embodiment of her mirror stage, where she perceives her own reflection in the form of her twin sister. This is subtly conveyed through Vīdā’s deliberate hand movements in front of her face to verify that she is not merely a reflection in a mirror (figure 11). The mirror stage represents a crucial juncture of intense psychological transformation, facilitating the emergence of a cohesive sense of self, albeit masking the underlying fragility of the unconscious mind with an illusion of stability. Paradoxically, Kīyān’s encounter with Vīdā disrupts Vīdā’s established self-perception, compelling her to confront the disconcerting realization that she has lived with a false sense of identity and parentage. Consequently, it can be inferred that Vīdā plays the role of Kīyān’s “Other,” a catalyst for Kīyān’s attainment of a genuine sense of identity. Interestingly, Vīdā’s expertise in repairing and restoring antiques is relevant to this illuminating encounter. In his husband’s words, Vīdā is “the best restorer of old pottery and other antique items.”12Maybe Some Other Time (02:04:42).

Figure 11: After visiting her twin sister Vīdā, Kīyān moves her hand to sides to make sure it is not a mirror. Shāyad Vaqtī Dīgar (Maybe Some Other Time, 1988), Bahrām Bayzāʼī (02:10:37).

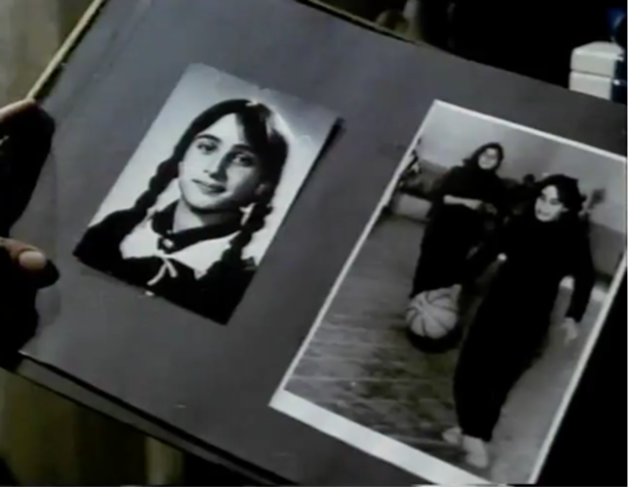

When Kīyān first meets Vīdā in the frame of Vīdā’s door—as if in a mirror frame—Vīdā is surprised by meeting someone so similar and therefore steps backward toward her husband. At this time, Mudabbir carefully scrutinizes a photograph of the twin girls in a family photo album (figure 12) while Vīdā explains that in her early childhood she had a sister but every time she asked about her, people said that she had gone on a long trip. The following shot displays Kīyān with her back facing the camera, overcome with tears. In this emotional moment, Vīdā recalls how their father had died and the hardships they faced, including hunger symbolized by the phrase “nān nabūd” (“there was no bread”).13Maybe Some Other Time (02:04:42). Evocative images of their mother engaged in domestic tasks like washing in basins and working with wool alongside other women appear on the screen.14See Mottahedeh, “Bahram Bayzai’s Maybe … Some Other Time,” for more detailed analytical discussion of the concept of Mother, cinema’s camera/screen; Bayzāʼī’s use of constant blocking of mirrors such as the doubling of the image of Mother in the antique cellar, and Vīdā’s door-frame scene; and the film’s emphasis on the present as a Benjaminian Jetztzeit (now-time—comprising the past and the present) that requests everyone’s responsibility. Subsequently, the film transports us back to the antique store, where the portrait painting of Vīdā extends and becomes a reflective mirror, revealing a reel of black and white film that shows the recollections and bleak memories of their mother’s circumstances that unfold before Kīyān, Mudabbir’s camera, and us as viewers. Like Diane in David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive (2001), Kīyān experiences a disintegration of identity and a fracturing of her psyche that leads to a series of melancholic surreal seances all caused by her desire to explore her past and family roots.15One of the film’s most iconic scenes in Mulholland Drive involves Diane’s confrontation with her reflection in a mirror, prompting her to confront the painful truth of her past. This moment of self-recognition is a pivotal moment in Lynch’s film, as it marks Diane’s acceptance of her own identity and the integration of her fragmented psyche. Other films that share similarities with Bahram Bayzāʼī’s Maybe Some Other Time can be Marnie (1964) the American psychological thriller directed by Alfred Hitchcock and Krzysztof Kieslowski’s The Double Life of Veronique (1991). They both explore themes of the unconscious, identity, and the supernatural and employ a dreamlike, surreal aesthetic.

Figure 12: Mudabbir checking the family album photos for a photo of the twins. Shāyad Vaqtī Dīgar (Maybe Some Other Time, 1988), Bahrām Bayzāʼī (02:11:24).

Desire, another central theme in Lacanian theory, is reflected in Kīyān’s search for her absent parents and for her identity to fill the “lack” (or absence) within herself. Lacan emphasizes the role of the lack inherent in our existence, stemming from the separation from the maternal unity experienced during the process of individuation. This lack gives rise to desire as individuals seek to fill this void and achieve a sense of wholeness. Desire, as a complex and elusive force shaped by the symbolic order is reflected in the absence of Kīyān’s father, and her search for her twin sister is an attempt to fill this lack or absence within herself.

Similarly, desire figures into Mudabbir’s character as well. Mudabbir’s suspicion towards Kīyān and his need to uncover the truth displays his desire to seek truth by shining light on the roots of his anxieties and uncertainties. Mudabbir’s fragile masculinity is challenged when he assumes that Kīyān has a lover. Mudabbir’s suspicion is a manifestation of his desire to seek and resolve his anxieties and uncertainties. According to Lacan, masculinity is a defense mechanism against the fear of castration but also a symptom of the male subject’s vulnerability.16Jacques Lacan, Écrits: The First Complete Edition in English (New Yok: Norton, 2006), 239. Thus, Mudabbir’s masculinity is precarious and dependent on recognition and authorization by the symbolic order that structures the social norms by which couples need to stay faithful in a marital tie.

Bayzāʼī deliberately tackles Kīyān’s complex struggle with her identity, using powerful symbolism, visuals, and the setting of the antique store to convey her profound sense of alienation. This is exemplified through the poignant depiction of a fish out of water, which serves as a metaphor for her deep suffering due to her lack of a solid sense of self. The first instance occurs in real life, following a heated dispute with Mudabbir.17Maybe Some Other Time, 01:38:21. Kīyān suddenly drops the jar of fish, which breaks, leaving the fish thrashing on the floor. This visual representation poignantly captures her deep-rooted anguish and the overwhelming sense of not belonging. Later, in the account of her mother’s past in Tehran, we see a fish out of water too, which communicates the emotional turmoil and existential crisis that Kīyān experiences. Furthermore, reminding cinephiles of similar scenes in the Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky’s film The Mirror (1975), Bayzāʼī uses slow-motion impressionist black and white and surreal dream scenes of the streets of Tehran in an earlier era including shots of a horse carriage and orphanage. Maybe Some Other Time and The Mirror both use non-linear narratives that blur the line between reality and dream. Both films explore themes of memory and identity. However, Bayzāʼī and Tarkovsky use their particular visual motifs to draw attention to the subjective nature of memory. Tarkovsky uses reflective surfaces and water as visual motifs to represent the fluidity of memory. In contrast, Bayzāʼī employs distorted surreal imagery to represent the protagonist’s fragmented identity.

Camera-eye: The Film-Within-Film Scene

The French philosopher Gilles Deleuze’s concept of the “camera-eye” offers valuable insights into the complex interplay between the camera’s gaze, the spectator’s gaze, and the unconscious elements present in Bayzāʼī’s film narrative.

Deleuze’s concept of the camera-eye introduced in his book Cinema 1: The Movement-Image highlights the importance of cinema as a medium that can transform our perception of reality and create new ways of seeing the world.18Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 1: The Movement-Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1986), 2-3. The camera-eye is a way of seeing that is unique to cinema and is different from the way we see the world with our own eyes. Deleuze argues that the camera-eye is not simply a mechanical device that records images, but rather a creative tool that can transform reality. The camera-eye can capture movement and time in a way that is impossible for the human eye, and it can create new perspectives and ways of seeing the world. Deleuze also suggests that the camera-eye is not neutral, but rather has its own subjective point of view. The camera-eye can be used to express the filmmaker’s own vision and ideas, and it can also be used to manipulate the viewer’s perception of reality. For example, Alfred Hitchcock and Stanley Kubrick are filmmakers who use the camera as a creative tool.

Deleuze emphasizes the camera’s detached gaze and its ability to reveal unnoticed emotions and issues. Through Bayzāʼī’s masterful camera movements and direct references to the lens in the final scene, the audience is delicately immersed in Kīyān’s moment of catharsis. This is displayed by the enactment of her memory of her mother holding onto the back of a carriage following those who adopted Kīyān (figures 13-14). In this scene, the projected shadow of the carriage’s wheels on the wall behind Kīyān can be seen as the projection of her psyche that the camera captures and reveals, implying both the recording and projection of the unconscious onto the screen.

Figure 13: Kīyān and Vīdā’s mother holding onto the back of a carriage following those who adopted Kīyān. Shāyad Vaqtī Dīgar (Maybe Some Other Time, 1988), Bahrām Bayzāʼī (02:21:03).

Figure 14: The surreal enactment of the mother holding onto the back of a carriage in Haq’nigar’s house. Shāyad Vaqtī Dīgar (Maybe Some Other Time, 1988), Bahrām Bayzāʼī (02:20:57).

Apart from the importance of camera eye in the final scene, this scene displays the moment of Kīyān’s trauma and anxiety as a result of confronting a sense of loss and a desire to return to the pre-symbolic state of unity with the mother.

The film’s final scene brings together cinema, performance, psychology, and philosophy, all intertwining and communicating with each other. After an impressive theatrical enactment of Kīyān’s cathartic moment of finding out her identity through the mirror stage drama of visiting her twin sister Vīdā, Mudabbir congratulates Kīyān in wishing her “Happy birthday,”19Maybe Some Other Time (02:31:01). while Kīyān breathes fresh air and stretches her arms as if waking up from a deep sleep (figures 15-16). This reference to Kīyān’s birthday highlights the significance of the mirror stage as the signifier of the birth of the “subject/self”—the moment of self-recognition and the formation of her subsequent subjectivity/identity recorded before the camera eye.

Figure 15: Kīyān stretches her arms as if waking up from a deep sleep. Shāyad Vaqtī Dīgar (Maybe Some Other Time, 1988), Bahrām Bayzāʼī (02:30:49).

Figure 16: Mudabbir celebrates her birthday by presenting her with a bouquet of flowers. Shāyad Vaqtī Dīgar (Maybe Some Other Time, 1988), Bahrām Bayzāʼī (02:31:01).

Furthermore, the final scene in Haq’nigar’s house where Mudabbir and his crew gather to capture and chronicle the twins’ meeting cleverly highlights the self-reflexivity of the film-within-film technique which asks for the audience’s active engagement with and contemplation about the situation (figures 17-18). Notably, Susan Taslimi remarkably portrays the roles of the mother, Kīyān, and Vīdā, effectively blurring the lines between the characters, thus seamlessly integrating their performances into the overall production of the film (figures 19, 20, 21).

Figures 17-18: Direct reference to camera lens and filmmaking equipment. Shāyad Vaqtī Dīgar (Maybe Some Other Time, 1988), Bahrām Bayzāʼī (02:10:53).

This self-reflexive address to the film-within-film technique drags the audience’s attention into the enacted self-discovery scene and asks them to subtly think about what is happening before them on the screen.

In addition to focusing on the psychological dimensions of the characters, Maybe Some Other Time equally emphasizes the technology of film as a means of psychological investigation and expression. The reference to camera and sound recording equipment casts a nostalgic spell over modern movie enthusiasts, transporting them back to the golden era of 33mm celluloid on the silver screen. Notably, the film’s engagement with film technology is addressed by Mudabbir’s job as a documentary commentator; his dubbing studio; his office full of film photos and the poster of a film made by the Japanese filmmaker Kenji Mizoguchi; the projection of the documentary onto the screen behind him; and especially the dimly lit dubbing room, accompanied by the gentle whir of the projector as it illuminates the cinema screen and the looming figure of Mudabbir standing before it.

Figures 19, 20, 21: Kīyān (02:11:37), Vīdā (02:09:49), and their mother (02:15:10) played by Sūsan Taslīmī. Shāyad Vaqtī Dīgar (Maybe Some Other Time, 1988), Bahrām Bayzāʼī.

Archives, the Unconscious, and Identity

The archive is a site of memory and forgetting, a place where the past is preserved and repressed, where the dead are remembered and forgotten.20Marlene Manoff, “Theories of the Archive from Across the Disciplines,” Portal: Libraries and the Academy10, no. 1, (2010): 9-25, 23.

Archives are the unconscious of a culture, the place where the repressed, forgotten, and marginalized aspects of collective memory are stored and can potentially resurface.21Hal Foster, “An Archival Impulse,” October110 (2004): 3-22, 9.

Archives—consisting of various artefacts, records, and documents from the past—serve a dual role in the construction of identity. They are not only crucial for understanding and shaping our sense of self but are also subject to the unconscious desires and fears that influence their interpretation and utilization. Several notable films, such as Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane (1941), Wim Wenders’ Wings of Desire (1987), and Wes Anderson’s The Royal Tenenbaums (2001), explore the theme of archives and their significance within narrative. Maybe Some Other Time is perhaps the first and only Iranian film that explores antique collections and the antique store as an important setting to explore and unfold psychological conflicts.

According to Terry Cook, a prominent scholar in the field of archives, the definition of archives encompasses a wide range of media, including textual records, photographs, sound recordings, and electronic records. Archives are carefully selected for permanent preservation based on their enduring value.22Terry Cook, “What is Past is Prologue: A History of Archival Ideas since 1898, and the Future Paradigm Shift,” Archivaria 43 (February 1997): 17-63, 29. Cook’s definition highlights the significance of archives as repositories of evidence that provide valuable insights into the past.

In Maybe Some Other Time, the influence of Kīyān’s past on her present is prominently portrayed through archival elements such as the antique store and references to family photos, and the Registry Office. As the film reaches its two-hour mark, the suspicious Mudabbir decides to discreetly trail Kīyān, who appears to be in a hurry to reach a mysterious destination. It is later revealed that Kīyān secretly visits her foster parents’ home, where she frantically sifts through the old family album while her foster parents try to calm her troubled mind (figures 22-23). These poignant moments intricately intertwine Kīyān’s psychological journey and her encounters with the archives of her own life.

Figures 22-23: Kīyān desperately sifts through the old family album (Left), while her foster father tries to calm her troubled mind (Right). Shāyad Vaqtī Dīgar (Maybe Some Other Time, 1988), Bahrām Bayzāʼī (01:52:00).

Later, in a dreamlike scene, Kīyān sees that all the recorded files in the archives of the Registry Office are burnt. Furthermore, once at home on the phone with the Registry Office she anxiously says: “Sometimes I think I am someone else. Sometimes I think I am not myself. No one responds to my requests. They need official requests. I can’t rely on their reply. Why do they burn the old files?”23Maybe Some Other Time (00:56:48).

Figures 24-25: Kīyān looking through her childhood’s photos in her family photo album. Shāyad Vaqtī Dīgar (Maybe Some Other Time, 1988), Bahrām Bayzāʼī (00:19:57).

Kīyān’s family photo album and the Registry Office serve as recurring motifs, both in her waking reality and in her dream sequences. These archives play a vital role in shaping her understanding of self and the events that unfold in the narrative. Through its exploration of Kīyān’s relationship with personal archives, Maybe Some Other Time invites viewers to contemplate the complex interplay between personal archives and the construction of identity, highlighting how the past continues to reverberate in the present. Family archives are not simply repositories of information but are also “sites of memory and identity construction,” and they can help individuals have a deeper understanding of one’s identity and history.24Jennifer Wood and Maria Tamboukou, “Family Archives: An Autoethnographic Exploration,” Life Writing 14, no. 1, (2017): 19-33, 20. By dipping into the realm of archives, Maybe Some Other Time illuminates the dynamic relationship between memory, identity, and the preservation of historical evidence.

As a pivotal setting, the captivating antique store not only serves as a key initiating location but also holds the essence of an archive, addressing implications surrounding the concept of collection. Mudabbir’s first visit to the antique store is very important as the antiquarian enthusiastically explains the antique items that have historical significance such as “the shield of Shah Ismā‛īl Safavī… the Ottoman’s weapon used in the Battle of Chaldiran … the Queen Victoria’s clock sent to Nāsir al-Dīn Shah (Qājār)”25Maybe Some Other Time (01:12:05). and “the stirrups of Sultan Mahmūd, the helmet of Uzun Hasan, and the seal of Genghis Khan.”26Maybe Some Other Time (02:00:33). Mudabbir’s excited and immediate comment—”The past of the world is here!”27Maybe Some Other Time (02:00:42).—turns out to be ironically correct insomuch as Kīyān’s past can be explored in the same archive, as this is where she meets the portrait of her twin sister that first led her to her horrifying recollection of the past.

Further, a comment made by Haq’nigar reinforces the ambivalent importance of archives such as antique stores. Haq’nigar notes that there are two different views about antique collections, that they are either “the rubbish heap of memories” or “the treasury of history.”28Maybe Some Other Time (01:12:29). Finally, the antique store serves as a metaphor for the archives of the unconscious mind in Maybe Some Other Time, as this is the place where Kīyān first met her double, in the guise of Vīdā’s portrait, which functions as the first reference to the Lacanian mirror stage in the film.

The fact that the antique store is in a cellar reinforces the idea of its relation to that which is repressed in the unconscious. As explained before, Kīyān’s first encounter with her twin sister’s image in the antique store is so irritating that she desperately rushes out of the store after seeing the portrait. However, it is this same archive that also opens up the door to her repressed memories that, in cathartic way, comfort and heal her. Within the same archive, Kīyān stumbles upon her “mirror image” reflected in Vīdā’s portrait,29Maybe Some Other Time (01:59:53). a moment that is later enhanced by her visit to Haq’nigar and Vīdā’s home.30Maybe Some Other Time (02:11:03). This convergence of events brings a therapeutic revelation for Kīyān, finally allowing her to attain a genuine sense of self and identity.

As Kīyān visits Vīdā and Haq’nigar in their house, Mudabbir notices the perplexed expressions on their faces. In response, he sheds light on Kīyān’s identity crisis by explaining, “My wife has recently been afflicted by a peculiar ailment. She yearns to understand why she possesses no photographs with her parents prior to the age of five.”31Maybe Some Other Time (02:07:18). Similarly, the meeting of the twins holding each other in their arms serves as an enlightening moment for Mudabbir, who exclaims, “Now I understand the meaning of the orphanage, the Registry Office. … The elderly couple are not her biological parents.”32Maybe Some Other Time (02:07:18).

Vīdā’s first account of her past after meeting Kīyān displays how the mirror stage is important for the two sisters’ identities: one raised in orphanage and foster parents, the other raised by her real mother; Vīdā: “I, in my childhood, when I was very little, had a sister about whom whenever I asked, I was told that she has been travelling.”33Maybe Some Other Time (02:13:01). As Clare Brant writes, “The unconscious is at work in archives, which contain fragments of a life, documents which may be purposefully or unconsciously saved, or which may be retained in order to ‘re-member’ a past self.”34Clare Brant, “Life Writing and the Unconscious: The Use of Archives in Autobiographical Narrative,” Life Writing 6, no. 1, (2009): 67-78, 71. In Kīyān’s case, the antique store works as a part of history that contributes to the demystification of her history.

Conclusion

The exploration of Iranian identity, particularly that of Iranian women, has been a recurring theme in Bayzāʼī’s body of work such as Haqāyiq Darbārah-i Laylā Dukhtār-i Idrīs (Facts about Leila, the Daughter of Idris, 1975) and Sag Kushī (Killing Mad Dogs, 2001). Additionally, his fascination with the use of mirrors to address mythological truth, history, and symbolism is also evident in many of his films such as Charīkah-i Tārā (Ballad of Tara, 1979) and Musāfirān (Travellers, 1991). However, it is unclear whether Bayzāʼī’s inclusion of mirrors in Maybe Some Other Time was influenced by Lacan’s concept of mirror stage. Nevertheless, the direct references to archives, the camera, and cinema technology in addition to the mirroring images of the twin sisters in Maybe Some Other Time opens up doors for psychological approaches for interpretation and analysis of themes such as the unconscious, identity, and mirror image. Furthermore, when considering Kīyān’s referring to her family photo album, her frequent calls and visits to the Registry Office, and the significant role of Mudabbir’s antique store as a central location in the film, it is evident that for Bayzāʼī’, the archives hold immense significance as a space that houses tangible remnants of the past, ultimately influencing the formation of one’s identity.

The music and sound effects in Maybe Some Other Time contribute significantly to creating a suspenseful thriller with a surreal atmosphere, particularly during dream sequences. Bābak Bayāt’s music is reminiscent of the works of the American composer Bernard Herrmann (1911-1975), and some of Alfred Hitchcock’s suspense thrillers such as Vertigo (1958), Psycho (1960), and Marnie (1964). However, Maybe Some Other Time exemplifies the Iranian New Wave aesthetic of introspective storytelling by focusing more on character and emotions over plot.

Bahrām Bayzāʼī is a highly regarded figure in Iranian cinema and culture, known for his long-time contributions as a filmmaker, playwright, researcher, educator and theatre director. He is recognized as one of the pioneers of Iranian New Wave cinema, using a poetic and visually stunning style to explore complex social and cultural issues, especially a progressive gender politics in Iran. Additionally, he is an innovative theatre director who incorporates traditional Iranian theatrical forms and techniques into his contemporary work. Bayzāʼī’s films serve as an invaluable laboratory where the timeless and modern aspects of performing arts seamlessly merge, appealing to individuals who appreciate the magic of theater, cinema, cultural legacy, artistic expression, and their enchantments.

Cite this article

This article explores Bahrām Bayzāʼī’s Maybe Some Other Time (1988), a psychological drama that delves into themes of identity, repression, and self-discovery in post-revolutionary Iran. The narrative follows Kīyān as she confronts her unconscious through mirrors, dreams, and archival objects, juxtaposed with Mudabbir’s struggle with jealousy and vulnerability. Drawing on Freudian and Lacanian psychoanalysis, the article examines Bayzāʼī’s use of cinematic devices, such as flashbacks and film-within-film techniques, to portray fragmented identities. By contextualizing the film within Iran’s socio-political shifts, the article highlights its symbolic exploration of gender, memory, and the transformative power of self-realization.