Tahmīnah Mīlānī’s The Hidden Half: The Art of Archetypes and Flashbacks

A sad little fairy dies at night from a kiss

And at dawn is re-born with a kiss

Reborn (Tavalludī Dīgar) by Furūgh Farrukhzād

Figure 1: Poster of the film The Hidden Half (Nīmah-yi Pinhān), directed by Tahmīnah Mīlānī, 2000.

In Tahmīnah Mīlānī’s film The Hidden Half (Nīmah-yi Pinhān, 2000), the narrative unfolds as a fictional account of a female activist’s personal history, encompassing the political upheaval of the 1979 Iranian Revolution, her romantic experiences, and her encounters with everyday life. The central plot focuses on a judge’s journey to Shiraz to visit a political prisoner facing execution. Concurrently, the judge discovers a hidden facet of his wife Farīshtah’s (Angel) past, as she recounts her own activist experiences through voice-over narration and diary flashbacks.

The judge, an American-educated envoy appointed by the reformist government’s newly elected president, is tasked with addressing the social injustices of the previous two decades by listening to grievances brought before the judiciary and potentially enacting reforms. Unbeknownst to him, his wife’s activism mirrors the struggles of the woman he is investigating—an ironic revelation only uncovered through her letters. Externally, the couple appears to lead a peaceful, middle-class life with their two children, yet their seemingly idyllic existence conceals Farīshtah’s hidden past as a member of a guerilla organization, kept for over two decades from the public and even her loving husband.

Tahmīnah Mīlānī faced charges of treason and threatening national security following her groundbreaking attempt to address the sensitive topic of leftist groups’ roles in early revolutionary uprisings. Her bold narrative approach, which challenged prevailing historiographies, quickly drew the ire of the government. Even two decades after the revolution, Mīlānī’s exploration of such contentious themes continued to provoke strong reactions, underscoring the enduring tension surrounding these historical and political subjects.

To a significant degree, The Hidden Half serves as a semiautobiographical reflection of its filmmaker, Tahmīnah Mīlānī. Like Farīshtah, Mīlānī began her journey as a political activist during her college years, when she too faced persecution for her beliefs.

Farīshtah’s youthful involvement with a guerrilla faction is portrayed with both naiveté and fervor, embodying a passionate idealism that may sound simplistic in her midlife. It is this idealism that contributed to her allure, including her appeal to the older gentleman she once loved, Rūzbah Jāvīd. Echoing elements of Makhmalbāf’s A Moment of Innocence (Nūn u Guldūn, 1996) The Hidden Half encourages a critical reevaluation of the idealistic past. Through its narrative, it critiques the repression that followed the revolution while also giving voice to histories and stories that had been silenced.

Following its release, The Hidden Half was swiftly labeled as seditious and subsequently banned. Tahmīnah Mīlānī faced severe repercussions, with Iran’s judiciary arresting and imprisoning her on charges of “abusing arts as a tool for actions to suit the taste of the counterrevolutionary and muhārib [those who fight God] grouplets.”1ADD CITATION Mīlānī’s empathetic portrayal of dissident organizations and political prisoners was interpreted as an endorsement of their oppositional stance, sparking strong condemnation from authorities. Her film’s reception underscores the fraught tension between artistic expression and political censorship in postrevolutionary Iran.2Hamīd Mazra‛ah, Farīshtah-hā-yi Sūkhtah: Naqd va Barrasī-i Fīlm-hā-yi Tāhmīnah Milānī (Tehran: Varjāvand, 2001), PAGE NUMBER?

Tahmīnah Mīlānī was fully aware of the potential political sensitivity surrounding The Hidden Half. In an interview with the World Socialist Website (WSWS), she acknowledged the risks, stating, “With The Hidden Half, I understood that it could lead to my arrest and imprisonment, but I was an established director and felt it was my duty to make this film. I had to do it for all those who had been exiled or killed.”3See Richard Phillips, “Iranian Filmmaker Faces Death Penalty in Upcoming Trial: Iranian Director Tahmineh Milani Speaks with WSWS,” World Socialist Web Site, September 29, 2006, accessed April 29, 2025, http://www.wsws.org/articles/2006/sep2006/mila-s29.shtml. After prominent international filmmakers, including Francis Ford Coppola and Oliver Stone, advocated for Tahmīnah Mīlānī by writing letters on her behalf, she was released from her week-long incommunicado detention. Her family endured several months of legal uncertainty and tension before the charges against her were ultimately dropped, bringing a resolution to her ordeal.4Richard Phillips, “Iranian Filmmaker Faces Death Penalty in Upcoming Trial: Iranian Director Tahmineh Milani Speaks with WSWS,” World Socialist Web Site, September 29, 2006, accessed April 29, 2025, http://www.wsws.org/articles/2006/sep2006/mila-s29.shtml.

Figure 2: Portrait of Tahmīnah Mīlānī, Iranian director.

Through her cinematic storytelling, Mīlānī reconstructed the lives of Farīshtah, the judge, and the imprisoned woman, prompting a critical reevaluation of the past. Her work engaged with the role of women in the revolutionary era and interrogated the complexities of female subjectivity in the sociopolitical context of revolutionary Iran through the use of cinematic storytelling techniques like flashbacks and creating archetypal characters.

Mirrors and Flashbacks

In The Hidden Half, the recurring use of mirrors as a visual precursor to the flashbacks is a deliberate and powerful storytelling device. The mirrors are employed not only to frame Farīshtah in moments of deep contemplation but also to signify her fragmented identity and the duality existing in her life. By reflecting her image, the mirror creates a meditative ambiance, allowing the audience to perceive Farīshtah as both a subject of the present and a vessel carrying memories of the past.

The coupling of mirrors and flashback technique serves an introspective purpose, urging the viewer to delve into the psychological layers of Farīshtah’s character. At the same time, it evokes an unsettling atmosphere, suggesting that her seemingly idyllic, present-day existence conceals a far more complex and untold reality. The mirror’s reflection becomes a metaphor for the hidden dimension of her life, inviting further investigation into her activist past and the secrets she has kept even from those closest to her.

Figure 3: The reflection of Farīshtah in the mirror. A still from the film The Hidden Half (Nīmah-yi Pinhān), directed by Tahmīnah Mīlānī, 2000. Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5gxPphnn_pQ (00:02:02).

Mīlānī’s use of mirrors emphasizes the act of looking inward while also creating an emotional dissonance, drawing attention to the tension between Farīshtah’s external appearance and her inner world. By intertwining this visual motif with the flashbacks, the film not only enhances its narrative depth but also challenges the audience to question the nature of identity, memory, and the stories that remain untold of the tumultuous past.

The film situates itself within the socio-political context of Muhammad Khātamī’s reformist government (1997–2005), a period marked by aspirations for civil liberties and inclusivity in Iran.5See Blake Atwood, Reform cinema in Iran: film and political change in the Islamic Republic, Columbia University Press, 2016, PAGE NUMBER This backdrop imbues the narrative with a deeper political resonance, as the crimes and injustices of the past are reinterpreted through the lens of the reformist agenda. The judge, portrayed by the late Ātīlā Pisiyānī, embodies this reformist ethos. As a conscientious envoy of the government, his role in addressing the appeal of a female prisoner on death row symbolizes the administration’s commitment to rectifying historical wrongs.

However, the irony lies in the convergence of the judge’s professional mission and his personal life. The prisoner’s case, emblematic of the unresolved injustices of the past, mirrors the hidden dimensions of his own wife Farīshtah’s activist history. This intertwining of the personal and political underscores the enduring impact of the past on the present, revealing how the silent histories of individuals resurface to challenge contemporary efforts at justice and reform. Through this narrative, the film critiques the complexities of addressing systemic injustices while navigating the personal and political entanglements that define them.

In her autobiographical letter, Farīshtah appeals to her husband not simply as a compassionate judge, but as a representative of justice in a reformist government—a government that professes ideals of moral integrity and pluralism. Her plea transcends the immediate case and calls for understanding and compassion devoid of biases and prejudices, emphasizing the importance of acting judiciously and conscientiously. Farīshtah’s act of revealing the shared experiences between herself and the political prisoner serves to humanize the prisoner’s plight, illustrating the denied possibility of redemption and the value of a second chance.

As Fakhreddin Azimi insightfully notes, Farīshtah’s intervention on behalf of the condemned woman “rekindles her submerged political commitment,” demonstrating that the struggles and sacrifices of the past—be it through love, activism, or risk-taking—can gain new meaning if they contribute to saving a life now threatened by rigid and ethically indifferent systems.6Fakhreddin Azimi, “The Hidden Half (Tahmineh Milani): Love, Idealism, and Politics,” in Film in the Middle East and North Africa: Creative Dissidence, ed. Josef Gugler (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2011), 72. By urging her husband to carefully examine the situation, she challenges him to uphold the principles of justice and reform that his government represents, and to transcend the bureaucratic banalities that have perpetuated harm in the past. Through this appeal, Farīshtah highlights the reformist judge’s responsibility not only to listen attentively but to act decisively with humanity and integrity, making her letter a powerful commentary on justice, morality, and the enduring legacy of personal and political commitments.

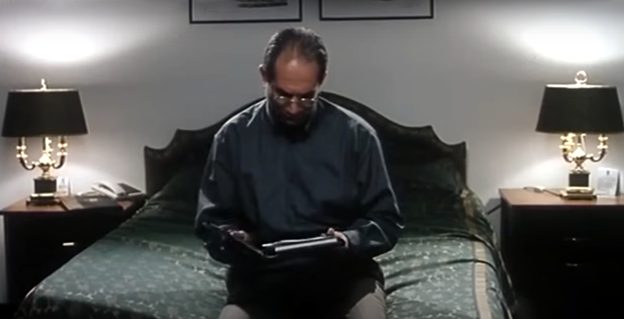

Farīshtah’s husband learns of her story not directly from her but in the silent process of reading her diary in a hotel room far from home, in the filmic form of a voice-over and multiple flashback scenes. It is Farīshtah’s voice from within the isolated hotel room, along with images, that narrates her past life, and the events that not only affected her “self” but impacted revolutionary Iran. The diary narration shows how she managed to overcome the odds, despite all political hurdles, and find refuge in an older woman’s house—a woman who would later become her mother-in-law—whereas the rest of her classmates met much worse fates: some were arrested, some fled into exile, some were sentenced to death by revolutionary courts, and some were executed. From the very outset, the juxtaposition of the imprisoned woman’s life seeking justice in the present day with that of the free Farīshtah leaves room for reflection, reassessment, and reevaluation of the historical events that led to the events.

Figure 4: Khusraw (played by Ātīlā Pisiyānī) reads Farīshtah’s diary. A still from the film The Hidden Half (Nīmah-yi Pinhān), directed by Tahmīnah Mīlānī, 2000. Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5gxPphnn_pQ (00:10:31).

In this vein, The Hidden Half juxtaposes present dilemmas with past political events, revisiting the revolutionary years when leftist factions were suppressed by the Islamic state. Farīshtah’s attire—a trench coat and wide pants—suggests her possible involvement with guerrilla movements, distributing pamphlets or preparing for armed resistance. These connections highlight the personal toll of political activism and the enduring impact of revolutionary struggles on individuals, urging a reconsideration of the view on historical injustices and to acknowledge their lasting echoes.

Archetypal Characters

The Hidden Half prompts a critical reassessment of an idealized past by employing archetypal characters. Among them is Mr. Rastigār (Salvation), the primary antagonist to Farīshtah during her academic years, who epitomizes the Islamic radical ideologues that spearheaded the “cultural revolution” in Iran between 1981 and 1984. During this period, universities were closed, and individuals like Rastigār—whose name ironically translates to “salvation”—emerged as figures of authority. Their unwavering commitment to a puritanical Islamic ideology led to the systematic Islamization of higher education, targeting faculty, students, and curriculum in the humanities and social sciences. The ideological purge aimed to eliminate individuals whose loyalty to revolutionary ideals was deemed suspect. Mr. Rastigār symbolizes the mechanisms of this Islamizing apparatus, overseeing the preservation of the dominant religious and ideological framework within academic institutions.

Figure 5: Mr. Rastigār with Farīshtah in the classroom. A still from the film The Hidden Half (Nīmah-yi Pinhān), directed by Tahmīnah Mīlānī, 2000. Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5gxPphnn_pQ (01:31:15).

Mīlānī portrays the reformist judge as an archetypal character embodying openness to change and progress, still within the dominant Islamic framework but with some more leniency. The judge’s gradual transformation is evident as he reads his wife’s diary, challenging his initial assumptions. Early in the film, he shares a collegial dynamic with Rastigār, but this shifts notably when Rastigār attempts to present his version of events, prompting the judge to continue engaging with his wife’s narrative instead. By the conclusion, the judge dismisses Rastigār during an interaction with the female political prisoner, signifying his evolving stance. This development reflects the reformist era’s ethos of reexamining past revolutionary decisions and embracing change.

Jāvīd (Eternity)

Rūzbah Jāvīd is another archetypal figure introduced through flashbacks that reveal his earlier love affair with the younger Farīshtah and his involvement in Iranian political activism. Azimi describes Jāvīd as enigmatic, exuding confidence, elegance, and gravitas, amplified by his reassuring demeanor. The film leaves Jāvīd’s origins and wealth ambiguous, aligning with his own critique of such values during a revolutionary speech. His ties to the Tūdah party are hinted at through the account of a woman claiming to be his wife, though his silence on this activism adds to his mystique. As editor of Science and Industry, Jāvīd’s connection with scholars and intellectuals underscores his significant role within cultural circles.

Figure 6: Rūzbah Jāvīd delivering a speech at a party. A still from the film The Hidden Half (Nīmah-yi Pinhān), directed by Tahmīnah Mīlānī, 2000. Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5gxPphnn_pQ (00:21:28).

Rūzbah Jāvīd actively establishes a link between the aristocracy and the everyday working and middle classes. This connection becomes evident when he proposes taking Farīshtah to England to live together in an egalitarian society. The narrative further enriches his role through the discovery of his marriage to a physically impaired wife (or ex-wife), symbolizing the fading aristocracy, and his earlier commitment to leftist activism, which adds depth to his bridging of social divisions.

Farīshtah’s love story unfolds within a hauntingly uncanny love triangle. She appears to be mistaken for Jāvīd’s first love, Māhmunīr—a woman who bears an extraordinary resemblance to Farīshtah and who vanished during the tumultuous events of the 1953 social movement. This resemblance not only deepens the psychological complexity of the narrative but also intertwines personal relationships with the larger political backdrop, highlighting the echoes of the past in the present. And presenting Farīshtah’s character as an archetypal one throughout history as well.

One of the most striking aspects of Rūzbah Jāvīd’s character is his agelessness, which reinforces his archetypal trait. When he reappears after two decades, his unchanged appearance creates a symbolic continuity across Iran’s social and political movements, from 1953 to 1979 and later to 1999. His mere presence serves as a bridge not only between these pivotal historical moments but also between the aristocratic elite and the everyday working and middle classes.

The director portrays Jāvīd as an archetypal figure representative of a generation of Iranians whose experiences and ideals set them apart from the other characters in The Hidden Half, each of whom embodies a distinct generational perspective within Iran’s political history. Jāvīd’s static composure and enduring presence evoke the collective memory of the 1953 coup and its aftermath—the overthrow of a prime minister who symbolized Iran’s national aspirations on the global stage. In doing so, Jāvīd becomes a living connection to this shared historical trauma, anchoring the past within the film’s contemporary narrative.

Figure 7: Rūzbah Jāvīd and Farīshtah talking at a party. A still from the film The Hidden Half (Nīmah-yi Pinhān), directed by Tahmīnah Mīlānī, 2000. Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5gxPphnn_pQ (00:52:09).

In a flashback, the young Farīshtah is shown rushing into Rūzbah Jāvīd’s Range Rover—a symbol of wealth and prestige in the early revolutionary period—upon encountering revolutionary guards at her doorstep. This scene vividly captures the profound fear she experiences, as the guards, presumed to be there to arrest her, embodying a dogmatic system that viewed even an eighteen-year-old student as a threat. This regime not only detained its youthful dissenters but sentenced many to death, exemplified by the imprisoned woman in Shiraz.

As mentioned earlier Mr. Rastigār, an early Hizballāhī, epitomizes fear and radical dogmatism, relentlessly shadowing Farīshtah from her college years to her married life. As an archetype of the uncompromising zealotry of early Islamic revolutionaries, his character underscores the film’s critique of their extremist pursuits. Although Mr. Rastigār ultimately fails to arrest Farīshtah or derail her academic pursuits, the recurring presence of his character across various scenes and historical periods accentuates his representation of pervasive fear.

In The Hidden Half, alongside Rastigār, a range of fear-inducing characters emerge, embodying the radicalism of the early revolutionary period. Among these is the infamous Zahrā Khānum, a real-life vigilante who initiated a witch-hunt campaign on Tehran University’s campus after the Islamic Revolution. Known for her rudimentary tactics of opposition, such as using sticks and fists against politically active students, Zahrā Khānum is portrayed in the film for the first time in a postrevolutionary context with depth and nuance, shifting her from a caricatured radical to a figure of serious contemplation.

In her scenes, Zahrā Khānum is accompanied by revolutionary guards, or komitehis, notorious for their suppression of dissenting voices. These guards would disrupt peaceful student gatherings, target activists distributing political flyers, and ultimately detain individuals with affiliations to leftist groups. Together, Zahrā Khānum and the kumītahis create an archetype of oppressive forces that stifled intellectual and political freedom, evoking the pervasive atmosphere of fear in the early years of the revolution. Zahrā Khānum, in particular, becomes a symbol of the threat faced by students navigating these turbulent times.

Figure 8: Zahrā Khānum, accompanied by the revolutionary guards known for suppressing dissent and targeting activists. A still from the film The Hidden Half (Nīmah-yi Pinhān), directed by Tahmīnah Mīlānī, 2000. Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5gxPphnn_pQ (00:52:38).

The archetypal characters in The Hidden Half are indeed crafted not to confine the narrative to simplified tropes but to widen the lens to encompass a more comprehensive sociopolitical landscape. By embodying broader dynamics—fear, radicalism, and social divisions—these figures serve as conduits for exploring the complexities of revolutionary Iran and its multifaceted history. Their presence encourages viewers to engage with the layers of political, cultural, and personal tensions throughout Iran’s postrevolutionary history rather than reducing them to singular, isolated events. It is a thoughtful narrative approach that adds depth and resonance to the film.

Farīshtah, like the other characters in The Hidden Half, embodies an archetype—specifically, that of a politically active woman with a distinct worldview. The revelation of her past ideological leanings exposes her political stance. However, the reformist government offers a glimmer of hope for societal progress, and it is this optimism that compels Farīshtah to share her story. She urges her husband to move beyond ideological stereotypes and rigid judgments, advocating instead for an evaluation grounded in facts and personal life trajectories that reflect her own experiences.

The narration of past events in The Hidden Half is delivered through Farīshtah’s voice-over, which goes beyond being merely her personal voice. It becomes emblematic of revolutionary Iran and connects her directly to the female prisoner in Shiraz. The film establishes this parallel by having the faceless, chador-clad woman begin her plea to the judge with the same opening words and the same dramatic tone as Farīshtah’s voice-over. This deliberate mirroring underscores their shared struggles and highlights the broader sociopolitical themes interwoven into their stories.

By drawing a deliberate connection between the female protagonist and the imprisoned woman, Mīlānī critiques the justice system’s treatment of early revolutionaries, particularly the prolonged incarceration and life sentences imposed on young activists. Beyond institutional critique, the film delves into the broader, more universal flaw of humanity’s tendency toward judgment without full understanding.

This theme culminates in the chance reunion of Farīshtah and Jāvīd, where Jāvīd admonishes Farīshtah for forming judgments before uncovering all the facts. Yet, the film deliberately leaves unresolved questions: Was Jāvīd’s ex-wife (or wife?) deceitful in her account of his past, or did she simply present an alternative version of the truth? Could undisclosed details have altered Farīshtah’s fateful decision to decline Jāvīd’s invitation to London? Similarly, the fate of the female prisoner remains unknown. Did Farīshtah’s diary influence the judge’s decision? Was the life sentence upheld, or did it offer a chance for redemption? These lingering ambiguities ensure that the narrative remains open-ended, encouraging reflection on concepts of judgment, truth, and justice across individual and societal dimensions.

Figure 9: Farīshtah meets Jāvīd’s wife. A still from the film The Hidden Half (Nīmah-yi Pinhān), directed by Tahmīnah Mīlānī, 2000. Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5gxPphnn_pQ (01:09:29).

The unresolved conclusion of The Hidden Half, leaving the impact of Farīshtah’s revelations on the female prisoner uncertain, creates a deliberate space for introspection. These lingering ambiguities invite the audience to contemplate profound themes such as justice, the act of judging, and the pervasive tendency toward being judgmental. By emphasizing the open-ended nature of the story, the film prompts reflection on the essential responsibilities and moral complexities faced by judges in contemporary Iran, and anyone else who needs to judge a situation. This intentional lack of closure transforms the narrative into a broader critique of societal and judicial systems while challenging the viewer to examine these concepts more deeply.

Conclusion

“Ah…

This is my share,

This is my share,

my share is the sky that a hanging veil takes it away from me,

my share is descending isolated stairwells,

and to be dispatched to exile and ruin,

my share is a tragic leisurely walk in the garden of memories,

and transpiring in the sadness of a voice that says,

I love your hands.”

Reborn (Tavalludī Dīgar) by Furūgh Farrukhzād

The ambiguous ending of The Hidden Half, along with its intricate layers of meaning, invites diverse, dynamic interpretations that challenge the established order and emphasize fragmented subjectivity. While the questions raised in The Hidden Half are vital for understanding the complexities of the historical period, its critique—particularly the suggestion that early revolutionary purges may have been flawed—presented a narrative that the revolutionary Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance (MCIG), and some other institutions, found intolerable. This opposition underscores the film’s audacious challenge to dominant historical interpretations, highlighting its subversive approach in addressing sensitive and often suppressed aspects of revolutionary history.7See Fakhreddin Azimi, “The Hidden Half (Tahmineh Milani): Love, Idealism, and Politics,” in Film in the Middle East and North Africa: Creative Dissidence, ed. Josef Gugler (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2011), 63–73.

Through its narrative, The Hidden Half unveils a history that had remained untold, offering others an insight into the struggles of women in post-revolutionary Iran as they navigated multiple identities—often at the expense of personal, social, and political aspirations. This struggle is depicted poignantly as women grapple with their desires within the constraints of societal norms. As Ziba Mir-Hosseini articulates, the film reflects “younger voices demanding personal freedom and questioning the whole notion of feqh-based gender relations.”8Ziba Mir-Hosseini, “Iranian Cinema: Art, Society and the State,” Middle East Report 229 (Summer 2001): 26–29.

Much like Farīshtah, numerous Iranian women navigate the intricate and often contradictory realities of urban life, where their identities are shaped by their ability to confront and overcome the social, political, and cultural hurdles of their daily existence. These identities emerge as multifaceted constructs, crafted both by societal expectations and the women’s own understandings of what is deemed acceptable. However, this identity formation is not static; it involves a continuous process of negotiation, driven by societal transformations that largely unfold independently of their agency rather than in collaboration with them.

In The Hidden Half, the process of reassessing one’s past transcends the personal and individual realm, becoming a societal and judicial imperative. The film presents the act of feminine reevaluation as a profound tool capable of informing judgment, even to the extent of overturning a life sentence. By shedding light on a feminine past—a narrative often overlooked yet integral to Iran’s historical and cultural fabric—the film highlights its continuing influence on the present. As a result, The Hidden Half not only critiques the mechanisms of justice but also emphasizes the essential role of women’s experiences and histories in shaping collective understanding and progress, making it a vital work of both cultural and cinematic significance.

Cite this article

A sad little fairy dies at night from a kiss / And at dawn is reborn with a kiss. These lines from Forugh Farrokhzād’s poem Reborn (Tavalludī Dīgar) evoke the cyclical death and renewal of feminine subjectivity—an image that frames Tahmineh Milani’s The Hidden Half (Nīmah-yi Pinhān, 2000). Through flashbacks, mirrored reflections, and diary narration, the film uncovers the suppressed revolutionary past of Farīshtah, whose personal history intersects with the case of a female political prisoner. As archetypal characters embody competing ideologies—radical zealotry, reformist moderation, and idealistic love—Milani crafts a critique of postrevolutionary justice and memory. The film’s interweaving of personal testimony with national trauma foregrounds the often-erased role of women in Iran’s political struggles. In doing so, The Hidden Half becomes both a cinematic intervention and a feminist counter-narrative—one that insists, like Farrokhzād’s poetry, that resurrection can come through truth, empathy, and the courage to speak the unspeakable.