The Cinematic and Cultural Legacy of Farrukh Ghaffārī

Introduction

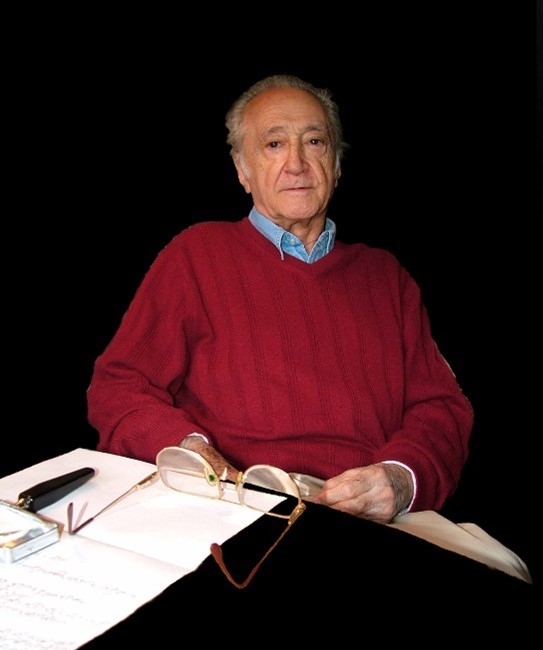

This article focuses on the life and professional career of Farrukh Ghaffārī (1922-2006), an outstanding cinematic and cultural figure in Iran. By covering various aspects of Ghaffārī’s life, including his early years and diverse roles such as a film critic, founder of the National Iranian Film Centre, film director, actor, Cultural Deputy of National Iranian Radio and Television (NIRT), and key organizer of Jashn-i Hunar-i Shīrāz (Shiraz Arts Festival), this article aims to provide readers with a comprehensive examination of his contributions and enduring legacy.

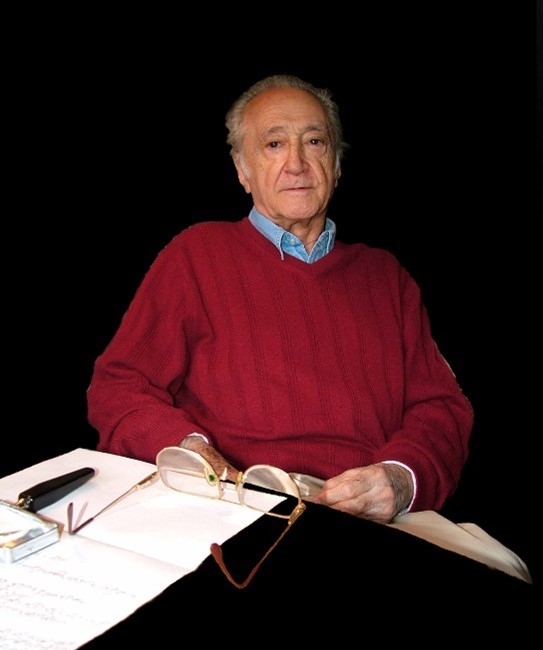

Figure 1: Farrukh Ghaffārī. photo by Parviz Jahed. August 2005.

Ghaffārī was a multifaceted figure in the history of Iranian cinema and distinguished himself as a leading filmmaker, film historian, film critic, and actor. His impactful roles extended beyond the screen as he assumed directorship at NIRT between 1966 and 1978, and organized Jashn-i Hunar-i Shīrāz (Shiraz Arts Festival) from 1966 to 1977. He was the visionary founder of Iran’s National Film Archive (Fīlmkhānah-i Millī-i Īrān) and stands as a luminary figure deeply connected to the cultural roots that grew into Iran’s New Wave Cinema movement.

Ghaffārī ’s enduring influence on the landscape of Iranian cinema holds paramount significance, yet it remains regrettably underappreciated. The true resonance of his cinematic works was stifled by the oppressive censorship imposed by the shah’s regime, and his contributions were unfortunately marginalised by contemporary Iranian film critics when his films were initially screened. As a profoundly influential figure, Ghaffārī played a pivotal role in shaping the film industry and cinematic culture, a contribution that extended far beyond his relatively limited filmography.

Ghaffārī’s Early Life

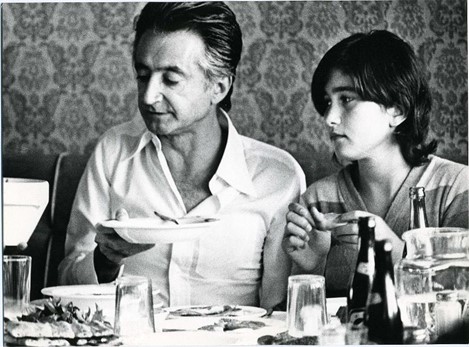

Farrukh Ghaffārī was born in Tehran on 26 February 1922. At the age of 11, he went to Belgium with his father, Hasan-‘Alī Khān Mu‘āvin al-Dawlah (1886–1976), also known as Hasan-‘Alī Ghaffārī, a high-ranking officer in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs during the Qājār and Pahlavi periods, and plenipotentiary minister (vazīr-i mukhtār) at the Iranian embassy in Belgium in the early twentieth century. He finished high school and began studying accounting in Belgium but did not complete his studies. Ghaffārī moved to France where he graduated in literature at the University of Grenoble in 1945. At that time, he was infatuated with cinema and started to write about films for local magazines and newspapers.1Parviz Jahed, Az Sīnimātik-i Pārīs tā Kānūn-i Fīlm-i Tihrān [From Paris Cinémathèque to Tehran Film Club, Interview with Farrokh Ghaffari] (Tehran: Nay Publication, 2014), 10. This and all further translations are by the author.

Figure 2: The young Farrukh Ghaffārī with his father Hasan-‘Alī Khān Mu‘āvin al-Dawlah. 1933.

Figure 3: The young Farrukh Ghaffārī at the age of 11 when he was studying in Belgium. 1933.

Ghaffārī as a Film Critic

In France, young Ghaffārī’s love for cinema flourished, leading him to delve into the realm of film criticism. He contributed insightful articles to various local magazines and newspapers as part of his cinematic exploration. Ghaffārī’s written reflections on the world of film found their way into the pages of prestigious French publications such as Positif, Jean Define, Variété, and Le Monde. His sojourn in Paris, as a devoted cinephile and frequent visitor to La Cinémathèque Française, deepened his passion for film culture and the rich tapestry of cinematic history. These experiences ignited within him the aspiration to establish a film club in Iran upon his eventual return.

In a November 1983 interview with Akbar I‛timād, Ghaffārī revealed that he had been a member of the French Communist Party until his return to Iran in 1949. In Iran, Ghaffārī was initially not affiliated with the Hizb-i Tūdah (literally “the masses party,” commonly known as the Tudeh Party). In the beginning, he had no knowledge of the Party, but he was later introduced to it by a friend:

Upon my return to Iran in 1949, a friend who was a Tudeh Party member approached me, mentioning that he heard about my affiliation with the French Communist Party. Confirming this, he urged me to fulfill my duty, explaining that the Tudeh Party was Iran’s communist party. Consequently, I readily joined the organization and became a member of the Tudeh Party of Iran.2Farrukh Ghaffārī, “Guftugū bā Akbar I‛timād [Interview with Akbar Etemad],” Oral History Program, Foundation for Iranian Studies, (November 1983 and July 1984), 5, https://fis-iran.org/fa/oral-history/ghaffari-farrokh/.

Despite this declaration, Ghaffārī made a contradictory statement in a later interview with me when he was suffering from cognitive decline. He claimed he was never a communist party member in France or Iran.3Jahed, Az Sīnimātik-i Pārīs, 46. Therefore, it makes sense to consider his initial claims more reliable, although I was unable to verify his involvement through documentation. Ghaffārī stated that after 1950, leftist intellectuals supported him and asked him to write film reviews in the Tudeh Party’s publications. He brought over whatever he had learned in France, referencing Georges Sadoul (1904-1967) and André Bazin. When he came to Iran, he gave his writings to a friend, who published his work in a political newspaper. Unaware that the newspaper was a Tudeh Party publication, Ghaffārī used a nom de plume, Mubārak, for security reasons.4Jahed, Az Sīnimātik-i Pārīs, 46.

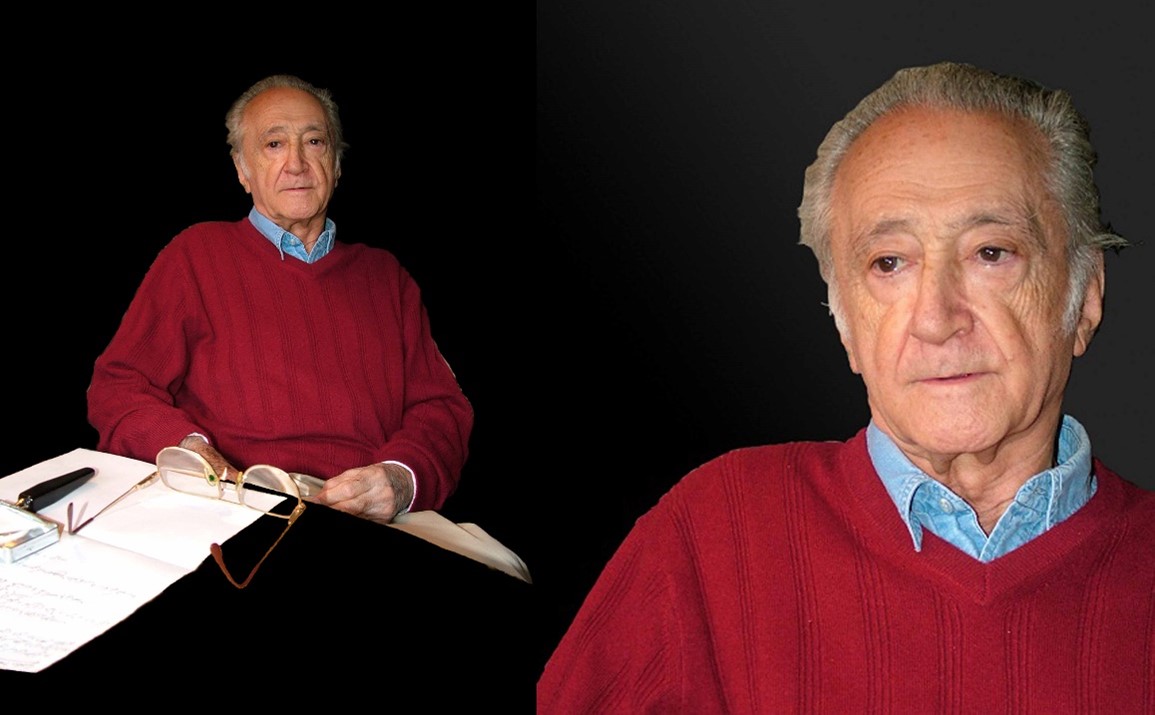

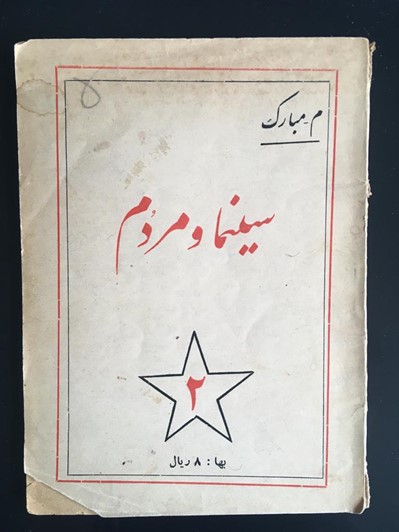

Figure 4: Farrukh Ghaffārī and Parviz Jahed at Ghaffārī’s residence in Montparnasse. Paris. August 2005.

Ghaffārī began publishing articles on cinema and film criticism. At that time, due to his Marxist leanings and his political engagement with the Tudeh Party, his articles were only published in the Tudeh Party’s leftist journals such as Kabūtar-i Sulh (Peace dove) and Sitārah-i Sulh (Peace star). In that period of time, the Tudeh Party’s activity had become secret and therefore its members were operating under pseudonyms. Therefore, the editors of party publications asked Ghaffārī to follow suit.

Ghaffārī maintained his support for the Tudeh Party and leftism until he heard First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev’s speech at the Twentieth Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (25 February 1956) which exposed Stalin’s crimes. It was at this point that he decided to part ways with the party:

I had retained my left-wing creed until after 1953 when Stalin died, and at the [Twentieth] Congress of the Communist Party Khrushchev stood behind a podium and exposed what a murderer Stalin was, and when I learnt that Stalin had spilt more blood than Hitler had in all his years in power, I cut myself off from all of it.5Jahed, Az Sīnimātik-i Pārīs, 47.

Having a political view towards cinema and film criticism, Ghaffārī started to challenge the predominant approach to film criticism in Iran: “A film critic should find fault with works of art, based on a particular social philosophy. Impartiality while judging and not getting any results from this judgment is a futile act.”6Farrukh Ghaffārī, Sīnimā va Mardum [Cinema and the people] (Tehran: self-published, 1950), 51. Ghaffārī asserted that a film critic should adopt a specific social philosophy when assessing works of art. He also emphasized the need to align with a philosophy that seeks to suppress these negative elements in art. This stance reflects Ghaffārī’s belief in the intertwined relationship between art, politics, and society, shaping his distinctive approach to film criticism.

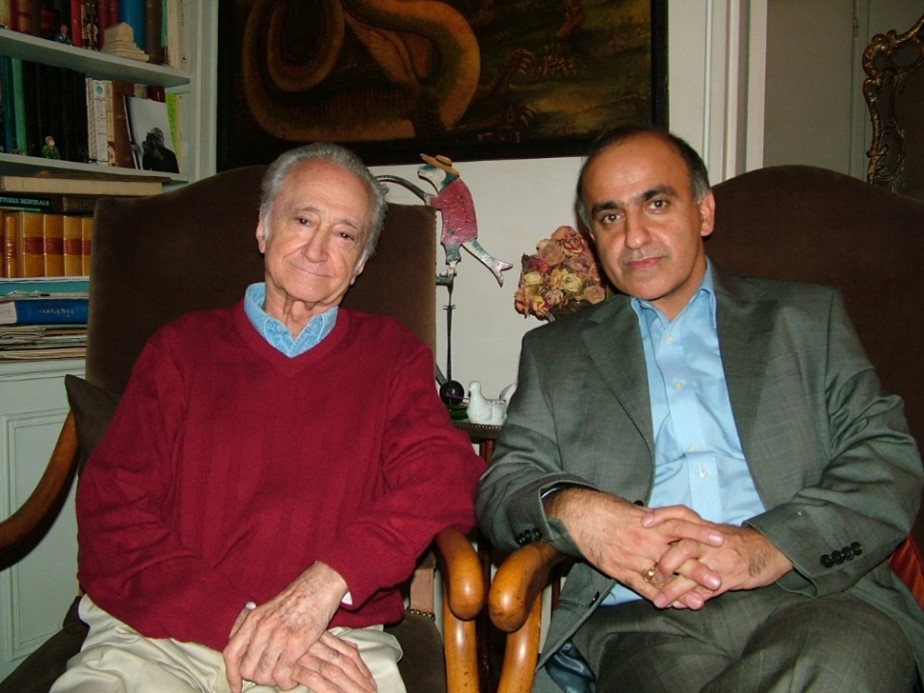

In 1950, Ghaffārī published a book entitled Sīnimā va Mardum (Cinema and the people), comprising his writings on cinema in Iran. The influence of French leftist film critics and historians like Sadoul is unmistakable in this work and his other critical writings on film. Sadoul was a French film critic and film historian who advocated for social and political cinema. Instead of focusing primarily on the intricacies of cinematic language, Sadoul believed in prioritizing the economic aspects of film. His emphasis lay in highlighting the socio-political influence of a film’s content, along with its ideological and moral dimensions. In a 2014 interview, Ghaffārī shared insights into his connection with Sadoul and their close relationship: “My friendship with Georges Sadoul developed post-World War II. While I knew of his pre-war cinema writings, I truly got to know him afterward. His perspectives on cinema were quite unique.”7Jahed, Az Sīnimātik-i Pārīs, 88.

Figure 5: Ghaffārī’s book Sīnimā va Mardum (Cinema and the People) published under the pseudonym M. Mubārak in 1950.

Ghaffārī’s friendship with Sadoul had a meaningful impact on his approach to film criticism and writing about cinema. Ghaffārī’s acknowledgment of Sadoul’s unique perspectives also indicates that this influence wasn’t merely about imitation but about appreciating and internalizing a distinctive way of thinking about cinema. Upon his return to Iran, the prevailing cinematic landscape was dominated by shallow, low-quality Fīlmfārsī productions, largely imitating Egyptian or Indian popular cinema, replete with musical and dance sequences. Ghaffārī observed that those involved in the prevalent Fīlmfārsī industry lacked a deep understanding of film and remained oblivious to the artistic dimensions of cinema in Europe and worldwide.

Similar to Sadoul, Ghaffārī focused his critiques of popular films primarily through a socio-political leftist lens, delving into their ideological and moral dimensions rather than conducting aesthetic analyses. However, in time, he grew disenchanted with these staunch leftist perspectives and voiced strong criticism of Sadoul for his pro-Soviet stance in film criticism, particularly in light of the revealed atrocities:

When I found out that my mentor Georges Sadoul showed great support for the Soviet Union and for their substandard films, I made an ideological departure from Sadoul very early on, and I adopted a different approach towards understanding the history of cinema from Sadoul’s ideological approach relating to the Soviet Union.8Jahed, Az Sīnimātik-i Pārīs, 47.

Subsequently, Ghaffārī commenced the publication of his film critiques in journals dedicated to film and culture, including Saddaf, Āshinā, Fīlm va Zindigī, and Sītārah-i Sīnimā. In his appraisals of Iranian mainstream cinema, Ghaffārī vehemently criticized the feeble narratives, one-dimensional characters, and superficiality that permeated the realm of commercial Iranian cinema. His intention was to improve the technical and aesthetic standards of Iranian cinema, fostering a more refined film culture and deeper cinematic knowledge among both filmmakers and the general audience in Iran. Disappointed by the vulgarity and incompetence of Fīlmfārsī, he sought to create a dignified cinema that would represent Iran’s national culture.

Despite his eagerness to contribute to Iran’s film industry, Ghaffārī faced disheartening conditions. The Iranian producer and director Ismā‛īl Kūshān offered him an opportunity to direct a film, but Ghaffārī realized he would not have creative control. In his review of Kūshān’s Sharmsār (The Ashamed, 1950), Ghaffārī criticized the film’s clichés and weak elements, highlighting its reliance on conventions used in low-grade foreign romances aimed at teenage girls who idolized Hollywood stars.9Farrukh Ghaffārī, “Naqd-i fīlm-i Sharmsār [A review of Ashamed],” Sitārah-i Sulh, no. 5 (August 1951): 46.

Ghaffārī coined the derogatory term “band-i tunbānī,” which literally means “girdle” in Persian, to depict the deficiencies in Fīlmfārsī. He believed that Fīlmfārsī’s fundamental shortcoming lay in its failure to confront genuine societal issues. He stood among the pioneering figures in the collection of historical documents related to Iranian cinema. In 1950, with the assistance of The Commission on Historical Research, he documented this archival endeavor in Iran, with certain portions subsequently entrusted to the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Although he aspired to compile his research into a book, he was unable to do so. Only select chapters found their way into the pages of the magazine ‛Ilm u Hunar (Science and art) in September 1951, while another segment appeared in volume five of Fīlm va Zindigī (Film and life) under the editorial guidance of Farīdūn Rahnamā. Regrettably, Ghaffārī’s involvement in the executive aspects of cinema and film production prevented him from pursuing his endeavors in film criticism. This also hindered his efforts to collect and analyze historical documents related to Iranian cinema for a comprehensive historical book on the subject.

The Establishment of the National Iranian Film Center

With the aim of enhancing the language of film and fostering cinematic culture in Iran, Ghaffārī made the significant decision to establish a film center similar to La Cinémathèque Française. In 1949, he founded the inaugural Iranian film club Kānūn-i Millī-i Fīlm-i Īrān (The National Iranian Film Center). In his article titled “San‛at-i Sīnimā dar Īrān” (The cinema industry in Iran), he voiced his apprehensions about the state of Iran’s film industry:

In our country, with a population of twelve million there are about sixty cinemas. This number is really disappointing . . . there should be many cinemas built in Iran. The country has the capacity for five hundred cinemas. These theatres will serve as a place for airing the artistic and cultural thoughts of people.10Farrukh Ghaffārī, “San‛at-i Sīnimā dar Īrān [The cinema industry in Iran],” Sitārah-i Sulh, no. 1 (September 1950): 11.

The main objective of the National Iranian Film Center was to cultivate a film culture among Iranian audiences by presenting artistic and culturally significant films, as well as showcasing world cinema masterpieces. To achieve this goal, the center conducted its inaugural British film season in 1950, an event resembling a festival, in collaboration with The British Film Council. In a bulletin published for this occasion, Ghaffārī criticized the commercial cinema imported to Iran, describing it as a dangerous tool in the hands of merchants interested only in profit, which was detrimental to Iranian audiences. He emphasized the need for intellectuals to combat these vulgar and misleading films and hoped that Kānūn-i Millī-i Fīlm would propagate and defend the real art of cinema, paving the way for the creation of an artistic cinema in Iran.11Jamal Omid, Tārīkh-i Sīnimā-yi Īrān, 1279-1357 [The History of Iranian Cinema, 1900-1978] (Tehran: Intishārat-i Rawzanah, 1995), 948-949.

Right from the outset, Ghaffārī embarked on the mission of nurturing Iranian film culture within the practical limitations of the time. During the British film season, he showcased films by renowned British filmmakers such as Michael Powell, Emeric Pressburger, Carol Reed, and also some British documentary films. The program’s objective was to acquaint Iranian audiences with the diverse genres and styles prevalent in British cinema. A parallel endeavor was undertaken with a French film season. The bulletin for this event explicitly conveyed Ghaffārī’s aspiration to foster artistic perspectives amongst general audiences.

The initial phase of The National Iranian Film Center concluded in July 1951 when Ghaffārī returned to Paris where he worked as an assistant to Henri Langlois at La Cinémathèque Française. Farīdūn Rahnamā (1930–1975), a distinguished Iranian filmmaker and another pioneer of modernist cinema in Iran, expressed his sorrow at the shuttering of the National Iranian Film Center: “The closure of the first Iranian film club was brought about by Mr. Ghaffārī ’s relocation to Paris. When the club first opened, genuine cinema enthusiasts were a scarce few, but the landscape has since changed.”12Omid, Tārīkh-i Sīnimā-yi Īrān, 955.

Ghaffārī later recounted his collaboration with Langlois and its influence on the formation of The National Iranian Film Center. He noted that he founded Kānūn-i Millī-i Fīlm in 1949 at Langlois’s suggestion, but it closed after twenty weeks due to his return to Europe. In 1951, at Langlois’s demand, Ghaffārī accepted the position of executive manager at the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF), which he held for five years from 1952 to 1957. According to Ghaffārī, during this time, he learned a lot from Langlois, “who was full of love, enthusiasm, and excitement towards cinema and had exceptional taste in choosing films.”13Jahed, Az Sīnimātik-i Pārīs, 45.

Upon Ghaffārī’s return to Tehran from Paris in 1957, the Film Center resumed its operations, but this time with a more deliberate and expansive approach. The Center was officially relaunched in November 1959 with the screening of Robert Flaherty’s documentary Louisiana Story (1948). Upon its revival, The National Iranian Film Center quickly became a beloved hub for Iranian cinephiles and individuals with an appreciation for art films. With the collaboration of Ibrāhīm Gulistān (1922-2023), Ghaffārī successfully screened masterpieces from European and American cinema, featuring films by masters such as Ingmar Bergman, Orson Welles, and representatives of modernist French cinema.

In 1973, the National Film Center underwent a name change, becoming the Fīlm-Khānah-i Millī-i Īrān (National Film House of Iran), and it remained under the administration of the Ministry of Culture and Art until the Islamic Revolution in 1979. Presently, it operates as a film department affiliated with the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance. The National Film Center played an outstanding role in promoting film culture amongst Iranian filmmakers. Many of the key figures in the New Wave of Iranian cinema, including Bahrām Bayzā’ī (1938-), Farīdūn Rahnamā (1930-1975), Dāryūsh Mihrjū’ī (1939-2023), Nāsir Taqvā’ī (1941-), Muhammad Rizā Aslānī (1943-), Kāmrān Shīrdil (1939-), and Bahman Farmān-Ārā (1942-), were members of the Film Center. It was through their affiliation that they were introduced, often for the first time, to significant film movements from around the world, such as Italian neorealism and the French New Wave. Hence, the National Film Center deserves recognition as an internal factor in the formation of New Wave Cinema in Iran.

Ghaffārī as a Film Director

Aside from his contributions to film criticism and the establishment of a film center aimed at promoting cinema culture in Iran, Ghaffārī is considered one of the forerunners of modern cinema in Iran. Although he was not a prolific filmmaker, he played a significant role, along with Ibrāhīm Gulistān and Farīdūn Rahnamā, in laying the foundations of modern cinema and paving the way for the emergence of Iranian New Wave Cinema. Upon his initial return from France to Iran in 1949, he made an unsuccessful foray into filmmaking, attempting to create an educational documentary on tuberculosis prevention intended to be titled B.C.G. for the Pasteur Institute in Tehran in 1950. However, this project remained incomplete as he later returned to Paris.

Figure 6: Farrukh Ghaffārī with Ibrāhīm Gulistān and his wife Fakhrī Gulistān in a restaurant in Paris.

Following the end of his collaboration with Langlois at La Cinémathèque Française in 1956, Ghaffārī embarked on his journey in filmmaking again. During his stay in France, he made a short film called Impasse (released in English as Cul-de-Sac, 1957) with the help of Claude-Jean Bonnardot (1923-1981) and Fereydoun Hoveyda (1924-2006), an Iranian diplomat who was also a member of the editorial board of Cahiers du Cinéma. The film revolves around a criminal incident unfolding within the confines of an apartment located in a secluded, dead-end alley. Subsequently, he ventured into the role of an assistant director, collaborating with renowned filmmakers such as Luis Buñuel and Jean Renoir. After returning to Iran in 1957, he was involved in making documentary films for various state organizations such as the National Iranian Oil Company, the Ministry of Industries and Mines, the Ministry of Health, and the Ministry of Culture and Art.

Ghaffārī made eight short documentary films about the oil industry in the 1960s, all of which were commissioned by the National Iranian Oil Company. In 1961 he made Raghā-yi Sīyāh (Black veins) about the oil pipeline extending from southern Iran to Tehran. One of his notable documentary films in this series was Zindigī-yi Naft (The life of oil, 1963), an industrial reportage that delves into the origins of oil, its extraction, and consumption. This film bears the influence of Ibrāhīm Gulistān’s style in industrial documentaries on oil. However, it distinguishes itself by its more didactic approach, characterized by a cold and matter-of-fact narration, in contrast to Gulistān’s documentaries which are known for their poetic tone and rhythm.

Ghaffārī’s Nūr-i Zamān (The light of the era, 1962), also centered on the significance of oil, however, its humorous storyline didn’t align with the expectations of the oil company’s management, and the film was not ultimately accepted. In 1962, at the behest of the French Committee of Anthropological Films in Paris, led by Jean Roche, Ghaffārī made a documentary film titled Qālīshūr-hā (Carpet cleaners). The film shed light on the lives of carpet cleaners and was later donated to the Museum of Anthropology in Paris.

Ghaffārī places the harsh socio-political circumstances of the nation, especially those faced by the underprivileged, at the forefront of his films. During a period when intellectuals generally displayed apathy, if not outright disdain, toward mainstream Iranian cinema, Ghaffārī’s aim was to strike a balance between the trends in cinema intended for mass audiences and a more artistically demanding form of filmmaking, closely aligned with the European arthouse style. He undertook the creation of his initial two films through self-financing, borrowing funds from his family, and even selling a portion of his mother’s estate.14Jahed, Az Sīnimātik-i Pārīs, 56.

Ghaffārī drew distinct inspiration from Italian neorealism and the French Nouvelle Vague. His filmography includes just four feature-length films: Junūb-i Shahr (South of the City, 1958), ‛Arūs Kudūmah? (Which One Is the Bride?, 1960), Shab-i Qūzī (Night of the Hunchback, 1964), and Zanbūrak (The Falconet, 1975). The first was considered the pioneering example of realist cinema in Iran, however, it was banned due to its harsh critical content. Night of the Hunchback also played a pivotal role in paving the way for the creation of artistic cinema in Iran, with the film serving as a foundational element of the Iranian New Wave movement.

In 1957, Ghaffārī established his film studio, Iran Nama, and embarked on creating his debut feature film, Junūb-i Shahr (South of the City). This film, depicting the impoverished areas of Tehran and the dire economic conditions endured by Iran’s underprivileged classes, was screened for just five nights in Tehran before being banned. The censorship board destroyed copies of the film, disapproving of its unflinching portrayal of these harsh realities. The narrative follows a young woman who works as a waitress in a café in southern Tehran to sustain herself and her child after her husband’s death. She attracts the attention of two tough guys with a longstanding rivalry, which intensifies as they vie for her affections.

South of the City was the first Iranian film to employ a neorealist approach in exploring the lives of marginalized members of society. A heavily censored and retitled version, Riqābat dar Shahr (Rivalry in the city), was released in 1962, conspicuously omitting Ghaffārī’s directorial credit. Ghaffārī explained his motivation for infusing the original film with cutting-edge realism. He and Jalāl Muqaddam, a filmmaker and scriptwriter, wrote the screenplay based on the lives of lower-class people. They explored the lower quarters of Tehran to find locations and saw the real lives of people that had never been captured in Iranian cinema, prompting them to revise the script to create realistic characters.

I felt that there are differences between the way characters spoke in the script and the real people that I saw in the street. So we changed the script and created realistic people instead of superficial characters. The main character of the film was a cowardly macho man who had delusions of being a champion. We also added a hoodlum and a prostitute.15Jahed, Az Sīnimātik-i Pārīs, 69.

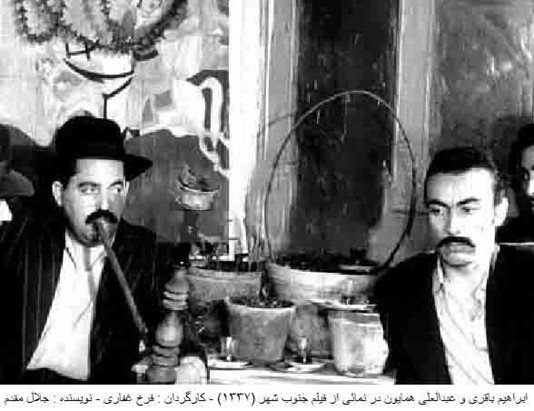

Figure 7: Ibrāhīm Bāqirī and ‛Abdul-‛Alī Humāyūn in a scene from Ghaffārī’s South of the City. 1958.

The censorship and subsequent destruction of the original version of South of the City by SAVAK (the secret police and intelligence service in Iran during Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s reign) were disheartening for Ghaffārī. He aimed to instigate a shift in mainstream and popular cinema in Iran, an endeavor prematurely stifled. Ghaffārī’s efforts differed from the elitist and intellectual approaches of directors like Farīdūn Rahnamā and Ibrāhīm Gulistān. He emphasized the need for national cinema to be rooted in Iranian culture and literature, authentically depicting the lives of ordinary people. He believed that good films, whether commercial or intellectual, should promote general understanding and knowledge among the audience:

Our filmmakers were in touch with what was happening around the world. They know that modern cinema has existed in the world for fifteen years. They got to know of the movements in Brazil, England, Japan, France and Ingmar Bergman’s film tendencies in Sweden and America. And in turn, they tried to create a movement in Iranian cinema.16Farrukh Ghaffārī, “Guftugū bā Farrukh Ghaffārī [Interview with Farrokh Ghaffari],” Farhang va Zindigī 2 (June 1970): 156.

Ghaffārī emphasized the need to bridge the significant gap between commercial films and art films, stating, “Steps need to be taken to fill the huge gap between the commercial films and art films.”17Ghaffārī, “Guftugū bā Farrukh Ghaffārī,” 156. He noted that films such as Farīdūn Rahnamā’s Sīyāvash dar Takht-i Jamshīd (Siavash in Persepolis, 1965), Ibrāhīm Gulistān’s Khisht u Āyinah (Brick and Mirror, 1964), and his own works South of the City and Night of the Hunchback were instrumental in establishing Iranian modern cinema.18Ghaffārī, “Guftugū bā Farrukh Ghaffārī,” 156. This new movement was visible not only among intellectual filmmakers but also within the commercial filmmaking sphere. However, Ghaffārī remained unwavering in his criticism of Fīlmfārsī and its catering to the most basic and vulgar tastes of the public. In his discourse regarding the duty of Iranian filmmakers, he articulated:

Any knowledgeable filmgoer can understand how the Iranian filmmakers are just copying the most vulgar and worthless cultural products to make their so-called populist films. I would say it is OK for filmmakers to make films to match the interests of people in order to make money, but they also have a responsibility to promote the level of general understanding and knowledge of the audience, otherwise we have no choice but to get closer to the tastes of the ignorant.19Ghaffārī, “Guftugū bā Farrukh Ghaffārī,” 161.

In South of the City, Ghaffārī made earnest efforts to combine elements of both artistic and commercial cinema. However, it failed to strike the desired balance, and the wider audience it aimed to enlighten did not turn out in large numbers. Additionally, the film faced disparaging critiques from eminent Iranian film critics of the era, such as veteran filmmaker and critic Hūshang Kāvūsī. Ghaffārī had criticised Kāvūsī’s film Hifdah Rūz bi I‛dām (17 Days to Execution, 1956), for what he deemed as its shallowness. It’s possible that Kāvūsī saw the debut of South of the City as an opportunity for reprisal and thus decided to hammer the film: “[South of the City] consists of a few scattered and ordinary scenes, and the only thing that has connected them together is the tape splicer of the editing, not cinematic thought.”20Hūshang Kāvūsī, “Naqdī bar Junūb-i Shahr [A review of South of the City],” Firdawsī 372 (25 November 1958): 43-45.

After the low box office turnout and poor critical reception of his second film, the comedy ‛Arūs Kudūmah? (Which One Is the Bride? in 1960), Ghaffārī made his third film, Night of the Hunchback in 1964. Night of the Hunchback was a modern satirical adaptation of one of the stories from Hizār u Yak Shab (commonly translated as either A Thousand and One Nights, or Arabian Nights). The original story is set during the time of Caliph Harun al-Rashid (r. 786-809), but Ghaffārī brought forward the setting to modern Tehran in another gritty portrayal of 1960s society. The film is a dark comedy about smugglers who try to hide the body of a dead hunchback who is left on their doorstep. Starting with a performance by a popular theatre troupe, Night of the Hunchback traces the unexpected demise of a comedian named Asghar Qūzī, the eponymous hunchback. In a farcical mishap, Asghar the hunchback becomes the unintended victim of a misguided practical joke instigated by his bumbling friends while having dinner together after their performance. Subsequently, his lifeless body assumes a central role in the darkly humorous film, passing from one individual to another.

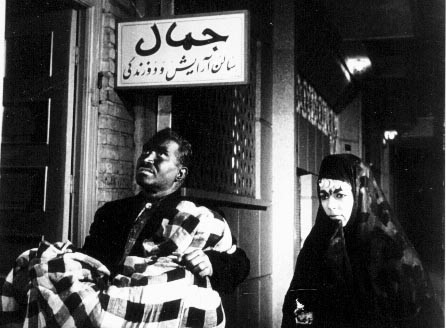

Figure 8: A scene from Ghaffārī’s The Night of the Hunchback. 1964.

Much like a Hitchcockian MacGuffin (i.e., a plot trigger), reminiscent of Harry’s body in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Trouble with Harry (1955), Asghar’s corpse in Night of the Hunchback serves as a catalyst, revealing the corruption, hypocrisy, and underlying fear in a society held captive by an almost subconscious dread and despotism. The hunchback’s cadaver descends upon a group of unscrupulous individuals entangled in a transgression (i.e., a smuggling ring), disrupting their tranquility like an unforeseen calamity from the heavens. This unexpected turn of events lays bare their genuine natures as they grapple with panic and hurried self-preservation efforts. The characters can be categorized into four bands: the naive and the simple-minded (such as the members of the troupe); smugglers and gangsters (the landlady and the owner of the barbershop); the drunken and oblivious; and the authorities that want to control society (the police force). The casting of prominent stage actors from that era, such as Parī Sabirī, Muhammad ‛Alī Kishāvarz, and Khusraw Sahāmī, reflects Ghaffārī’s distinct and artistic inclination.

Figure 9: Muhammad-‛Alī Kishāvarz in a scene from The Night of the Hunchback. 1964.

In Night of the Hunchback, Ghaffārī allegorically deals with the notion of fear within Iranian society after the 1953 coup d’état against Muhammad Musaddiq in the form of an attractive and joyful Iranian satire. A challenging and controversial film with a socio-realistic approach and an innovative narrative structure, the style of this film was totally new and shocking to the sensibilities of its day. It was unlikely to be welcomed by the ordinary people of society that the film was trying to address, particularly when public taste had been shaped by the simplicity of narrative and naive themes of Fīlmfārsī productions. As Ghaffārī indicates:

I wanted to somehow talk about the concept of fear not only in Iran, but within the Eastern mentality in my film, a fear of unknown origins. That is why I chose this particular story from Hizār-u Yak Shab [A Thousand and One Nights, also known as Arabian Nights] and worked on it for three years with Jalāl Muqaddam. Iranian audiences did not like the film because I heard that people [did] not like to see the corpse being dragged from one place to another, but it was the main element that led to the success of this film abroad. In my original draft, the hunchback would come alive in the end and for some reason we were forced to forgo his resuscitation. So, the difference between Junūb-i Shahr [South of the City] and Shab-i Qūzī [Night of the Hunchback] was that the first was related to the language and culture of ordinary people and the latter had a more personal aspect and gauged specific issues.21Jahed, Az Sīnimātik-i Pārīs, 109.

Ghaffārī’s exploration of fear and the challenges faced in aligning artistic vision with audience preferences adds depth to the narrative surrounding his cinematic endeavors. Night of the Hunchback garnered positive acclaim from international audiences when it was showcased at renowned film festivals like the Cannes, Karlovy Vary, and Locarno film festivals and was welcomed by Western film critics and historians like George Sadoul.

Despite some of its technical and narrative shortcomings, Night of the Hunchback has a unique place in the history of Iranian cinema. However, its reception among domestic viewers was predominantly unfavorable, although a few film critics, including Hazhīr Dāryūsh, held the film in high regard. Dāryūsh went so far as to proclaim that the film marked the birth of “real Iranian cinema.”22Hazhīr Dāryūsh, “Naqdī bar Shab-i Qūzī [Review of Night of the Hunchback],” Hunar va Sīnimā 7 (February 2, 1964): 17. With its darkly jubilant, dissonant, and satirical ambiance, Night of the Hunchback delved into critical societal issues within Iran. In his review of the film, Dāryūsh put forth the notion that:

Shab-i Qūzī addresses the current problems of society and intellectually criticises the different classes of people. But, the ingenuity of the filmmaker is to the extent that when in the last scene the police officer says: “The death of the hunchback unveiled many issues” it makes you contemplate and you do not have the peace of mind you had before seeing the film. But if you are not intelligent enough you cannot correctly find the reason for your discomfort. Something has been said, a fundamental statement about you and people like you, belonging to this time and this place. But a curtain of ambiguity has deliberately covered this utterance. In short, it is a film that will not mesmerise the stupid.23Dāryūsh, “Naqdī bar Shab-i Qūzī,” 17.

According to Ghaffārī, while his film was shown in six cinemas in Tehran, it was not well received by spectators. Despite its straightforward narrative, Night of the Hunchback failed to resonate with moviegoers due to its departure from the conventional appeal found in popular commercial Iranian films of the time. Ghaffārī believed that his film was “too modern” for audiences accustomed to the “Egyptian and Indian junk films” popular at the time.24Jahed, Az Sīnimātik-i Pārīs, 64. The comedic tone of the film was influenced by the French comedies of the 1950s, especially the films of Jacques Tati, but Ghaffārī gives it an Iranian flavor by relying on Persian traditional performing arts. It is also notable that Ghaffārī takes a critical and satirical approach towards upper class Iranians in this film.

Figure10: Ghaffārī in a scene from The Night of the Hunchback.

Coming from an aristocratic family himself, Ghaffārī was well aware of cultural preferences and behaviors of wealthy Iranians and was, therefore, able to convey this in a very effective manner by juxtaposing rock ‘n’ roll and Western forms of revelry with traditional attitudes. Ghaffārī’s profound knowledge of Iran’s traditional and ritual performing arts, such as ta‛zīyah and sīyāh-bāzī theater, enabled him to creatively use some of these attractive theatrical elements in his film.25Ta‛zīyah commonly refers to passion plays about the Battle of Karbala and the tragic death of Imam Husayn and his companions. Sīyāh-bāzī is a type of Iranian folk performing art that features a blackface, mischievous, and forthright harlequin that does improvisations to stir laughter. The whole story occurs within one night—one of the A Thousand and One Nights—happening in modern Tehran in the 1960s. Thanks to the narrative structure of A Thousand and One Nights and the appealing theatrical features of Iranian traditional comedy plays, Ghaffārī’s film successfully managed to create a balance between the grotesque, the mysterious, and a realistically critical and modern approach towards Iranian society.

The failure of Night of the Hunchback at the box office, coupled with the lukewarm response from Iranian film critics, left Ghaffārī discouraged. In response to these setbacks, he chose to shift gears, transitioning to roles in cultural management at NIRT and later the Shiraz Arts Festival, opting to step away from filmmaking. Despite this change in direction, Ghaffārī’s passion for filmmaking endured. A decade after the disappointment of Night of the Hunchback, he decided to rekindle his cinematic pursuits and made a comeback to the industry with a new film titled Zanbūrak (The Falconet, 1975).

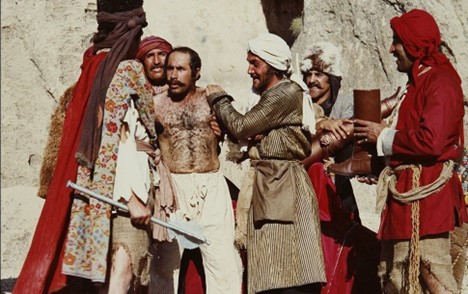

Ghaffārī’s fourth and last film, The Falconet was a farcical comedy inspired by Iranian folktales. The story occurs in the eighteenth century in central Iran and is about a soldier who gets lost in the middle of a war and is stranded from his squad following the disastrous defeat of their army. He is in charge of a zanbūrak, the film’s Persian namesake, a small swivel gun (i.e., a falconet) mounted on and fired from camels, which was a real technology used in Iran from the Safavīd Dynasty period to the end of the nineteenth century. The narrative structure of the film was inspired by the structure and style of medieval chivalric and picaresque literature such as Don Quixote, as well as Pier Paolo Pasolini’s filmic adaptations of The Decameron (1971) and The Canterbury Tales (1972).

Following the style of European and Persian picaresque literature, The Falconet consists of disconnected stories taking place in different settings with little exploration of the life of its main character. Similar to picaresque novels, the main character in The Falconet is a picaro who embarks on a lengthy, adventurous journey. Ghaffārī skillfully integrated elements of Persian classical literature into a comedic and humorous narrative featuring farcical characters and captivating events. Simultaneously, this narrative provided a critical examination of Iran’s history during the Qājār era, showcasing his profound mastery of Iranian culture and literature. He takes the structure from the picaresque genre in literature and cinema to depict a classical Persian story in a modernist way, which he had also used a decade earlier in his masterpiece Night of the Hunchback. The Falconet is a unique film in the history of Iranian cinema in terms of narrative, and, moreover, it produces a brilliant visual effect influenced by the artistic style of Persian miniatures.

Figure11: Farrukh Ghaffārī acting in a scene from his feature film The Night of the Hunchback. 1964.

Ghaffārī and the Shiraz Arts Festival

Ghaffārī served in an administrative role in Iranian state radio and television before the victory of the Islamic Revolution in 1979. In 1966, Ghaffārī was appointed the Cultural Deputy to Rizā Qutbī, head of NIRT. Being in this position allowed Ghaffārī to implement some of his innovative ideas in producing artistic films. As Muhammad ‛Alī Īssārī points out, “in 1969 NIRT established Telefilm, an affiliated company, to produce feature films as a commercial venture as well as for later release on television.”26Muhammad ‛Alī Īssārī, Cinema in Iran, 1900-1979 (Metuchen: The Scarecrow Press, 1989), 215. Ghaffārī’s contributions in this role significantly influenced the artistic direction of Iranian cinema during this period.

According to Īssārī, a number of young and foreign-trained filmmakers who had criticized the local film industry for its materialistic attitude took advantage of this offer and made several films in collaboration with Telefilm.27Īssārī, Cinema in Iran, 215. Ghaffārī thus made it possible for some young New Wave filmmakers such as Farīdūn Rahnamā, Parvīz Kīmīyāvī, Nāsir Taqvā’ī, Hazhīr Dāryūsh, and Muhammad Rizā Aslānī to realize their artistic visions with the funds provided by Telefilm. Ghaffārī then became the main organizer of Jashn-i Hunar-i Shīrāz (Shiraz Arts Festival), an annual culture and arts event sponsored by NIRT that was founded on the suggestion of Farah Pahlavi, the former Queen of Iran, in 1967 and ran for eleven years until 1977. The event unfolded as a grand celebration of both traditional and modern theater, music, film, and dance, set amidst the ancient ruins of Persepolis. It served as an exceptional rendezvous point for artists hailing from both the East and the West, a vision that Ghaffārī had ardently cherished throughout his life.28See Jahed, Az Sīnimātik-i Pārīs.

Over the course of eleven years, distinguished artists from the realms of theater, music, and cinema, both from Iran and across the globe, took part in the Shiraz Arts Festival including Peter Brook, Tadeusz Kantor, Maurice Béjart, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Ravi Shankar, Bismillah Khan, Yehudi Menuhin, John Cage, Jerzy Grotowski, Robert Wilson, Shoji Trayama, Parvīz Sayyād, Arbi Ovanesian, Bīzhan Mufīd, Ismā‛īl Khalāj, ʿAbbās Nā‛lbandīyān, Muhammad Rizā Shajarīyān, Muhammad Rizā Lutfī, Parīsā, Husayn ‛Alīzādah, Parvīz Mishkātīyān, Farāmarz Pāyvar, Ahmad ‛Ibādī, ‛Alī-Asghar Bahārī, Hasan Kasā’ī and Majīd Kīyānī.

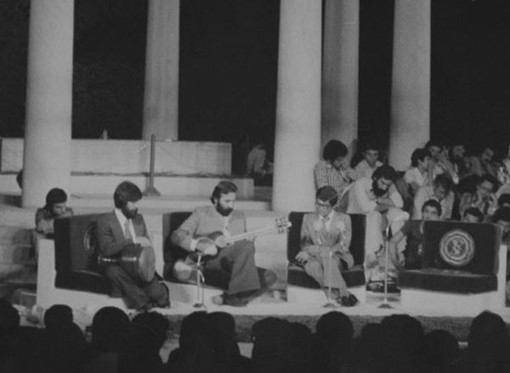

Figure 12: Shiraz Arts Festival, 1970, from left: Nāsir Farhangfar, Muhammad Rizā Lutfī, Muhammad Rizā Shajarīyān.

The Shiraz Arts Festival performed a pivotal role in introducing some of the world’s modernist trends in art and cinema to Iranians, shaping the artistic and cinematic sensibilities of a generation. Nonetheless, the festival encountered resistance from religious and traditional groups, particularly from mullahs and certain leftist intellectuals who opposed the shah’s regime. Mullahs and radical religious factions could not embrace the festival’s modernist and avant-garde approach to the performing arts at times. Their resistance against modern art did not stem from a lack of comprehension of these works. Instead, their objection primarily centered around the inclusion of nudity and what they perceived as the imprudence in depicting sexual content. According to them, such elements were considered morally corrupt and haram (forbidden or unlawful) and led the Muslim youths astray.

Meanwhile, Marxist and revolutionary intellectuals, while rejecting the traditional and ritual elements of the festival like ta‛zīyah, also opposed avant-garde and experimental theater performances by figures such as Arbi Ovanesian, and the works of Jerzy Grotowski and Peter Brook. They viewed the festival’s programs as “reactionary” and considered them to be aligned with the shah’s top-down modernization project financed by oil revenues. Additionally, Ghaffārī noted that traditional and regressive elements within the shah’s court, like Asadullāh ‛Alam (then minister of Royal Court and previously the thirty-fifth Prime Minister of Iran), consistently opposed the modernist artistic orientations and approaches championed by Farah Pahlavi and Rizā Qutbī, the festival’s director.

The controversial staging of the Hungarian play Pig, Child, Fire! (1977, Squat Theatre Group) during the eleventh edition of the festival in 1977 incited the ire of Ayatollah Ruhallāh Khumaynī (1902-1989) and other religious authorities, sparking protests against the shah and his progressive cultural and artistic policies. The provocative performance of the Hungarian Squat Theater group, which unfolded in the streets of Shiraz, provided religious authorities with ammunition to denounce the shah for promoting “obscenity and depravity” in society. Regarding the selection of this show for performance, Ghaffārī explained:

I hadn’t personally seen the show before its selection. Some individuals described it as the boldest and most avant-garde performance in Europe and suggested we bring it to Shiraz. We were cautioned about its explicit content and deemed it too provocative. Even Farah Pahlavi inquired about its nature from Qutbī, who initially deemed it risky and advised against its performance. Later, we realized the version presented in Shiraz was relatively ordinary. Despite the initial hype, the theatrical merit of the show was not particularly significant.29Jahed, Az Sīnimātik-i Pārīs, 127.

However, despite all the controversy and opposition it faced, the Shiraz Arts Festival not only played a vital role in shaping avant-garde and modern trends in Iranian theater and cinema but also facilitated the revival of some overlooked traditional Iranian performing arts, including ta‛zīyah, naqqālī, rū-hawzī, and sīyāh-bāzī.30For ta‛zīyah and sīyāh-bāzī see footnote 25. Naqqālī can be roughly described as publicly performed dramatic storytelling. Rū-hawzī is a comic form of traditional folk musical drama.

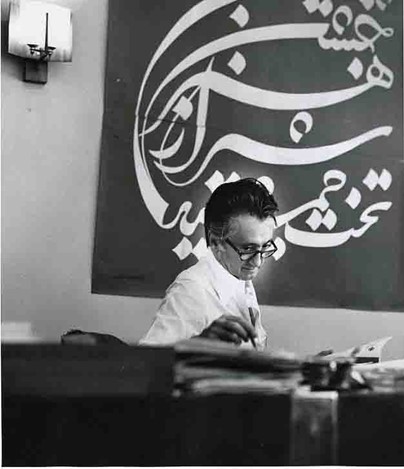

Figure 13: Farrukh Ghaffārī in his office where he was organizing the Shiraz Arts Festival.

Ghaffārī’s Acting Roles

Ghaffārī was also interested in the craft of acting. Nonetheless, his acting career, much like his work in film directing, was not prolific and encompassed only a handful of films. This included a role in his own film, Night of the Hunchback, where he took on the character of a woman hairdresser attempting to smuggle an antique out of Iran. Ghaffārī also performed a role in Parvīz Sayyād’s comedy film Samad and the Steel Armored Ogre (Samad va Fulād Zirrah-yi Dīv, 1972). His final acting role was portraying William Knox d’Arcy, the English oil explorer and a key figure in founding Iran’s oil and petrochemical industry in 1901, in Parvīz Kīmīyāvī’s surrealist postcolonial satire, O.K. Mister (1979). In this fictional narrative, a historical character arrives in a remote village in Iran with the intention of exploiting the land’s natural resources.

Figure14: Parvīz Sayyād in a scene from Ghaffārī’s Zanbūrak (The Falconet, 1975).

Ghaffārī’s Life in Exile and Death and Concluding Thoughts

The cultural and artistic journey of Ghaffārī came to an end with the advent of the Islamic Revolution in 1979. Following the Revolution, he was compelled to leave Iran and take up residence in France. Due to his association with the shah’s regime, he was denounced by the new Islamic government, rendering him unable to return to Iran, and he spent the rest of his life in exile in Paris. He married the renowned Iranian writer Mahshīd Amīrshāhī but they divorced after a few years. From this marriage, Ghaffārī has a daughter named Maryam. Ghaffārī passed away on 17 December 2006, succumbing to heart and kidney complications.

Figure 15: Ghaffārī with his daughter Maryam Ghaffārī.

By tracing Farrukh Ghaffārī’s journey from his early life to his significant roles in film, culture, and festival organization, this article aimed to illuminate the profound impact of this cinematic luminary on Iranian cultural history. In essence, this examination of Ghaffārī’s life and contributions serves as more than a historical account; it reveals his cinematic and cultural legacy and his artistic passion. By focusing on the various aspects of Ghaffārī’s life, the article invites readers to contemplate the profound impact of an individual who not only shaped the landscape of Iranian cinema but also left an indelible mark on the cultural heritage of the nation. Beyond the chronicle of his achievements, it is an ode to an enduring legacy that resonates far beyond the frames of a film reel or the echoes of a festival, underscoring Ghaffārī’s lasting influence and enriching our understanding of the dynamic interplay between cinema, culture, and the human spirit.

Cite this article

This article delves into the multifaceted life and career of Farrukh Ghaffārī (1922–2006), an influential figure in the development of Iranian cinema and cultural history. It traces his journey from a cinephile and film critic in France to a prominent filmmaker, cultural administrator, and advocate for the arts in Iran. As the founder of the National Iranian Film Centre, Ghaffārī played a pivotal role in fostering cinematic literacy and introducing Iranian audiences to international film movements. His directorial works, including South of the City and Night of the Hunchback, are examined as groundbreaking contributions to the Iranian New Wave, blending socio-political realism with artistic innovation.

The article also explores Ghaffārī’s legacy as a cultural organizer, notably as the architect of the Shiraz Arts Festival, a platform that brought avant-garde and traditional arts into dialogue and influenced a generation of artists. Despite facing censorship, political challenges, and exile following the 1979 Islamic Revolution, Ghaffārī’s impact resonates through his advocacy for a culturally rooted yet modern Iranian cinema. By re-evaluating his contributions, this article underscores the enduring significance of his vision in shaping Iranian cinematic and cultural identity, bridging artistic excellence with a commitment to social discourse.