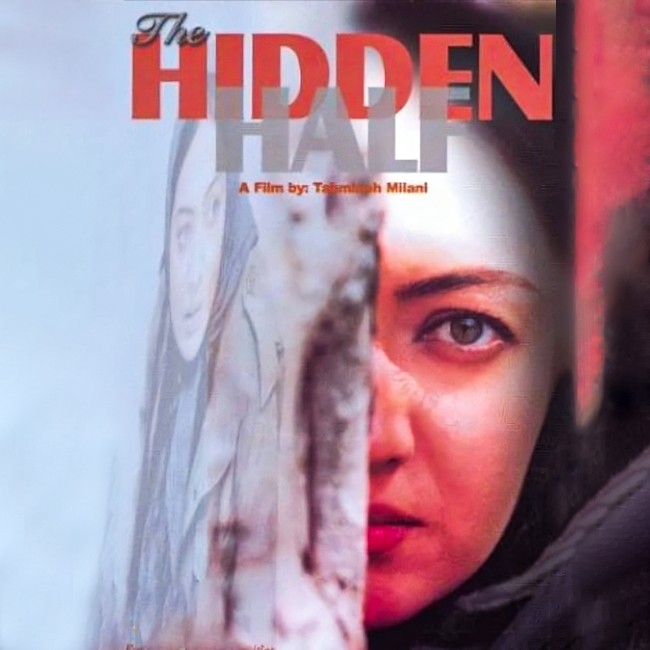

The Hidden Half

In The Hidden Half, the fictional narrative of a female activist’s life history generates a reevaluation of the political past, and throughout this self-reflective process not only the present but the nature of a woman’s subjectivity is questioned. This film’s plot revolves around the trip taken by a judge to see a female political prisoner on death row in Shiraz. The wife of this Islamic Republic’s American-educated presidential judge, Fereshteh (angel), ironically narrates a story of activism in the course of her diary flashbacks. Despite the fact that the protagonist seems to be leading a middle-class leisurely life with her husband and two young children, the presumably idyllic setting has an element amiss. It is only in Shiraz that the husband comes to understand his wife’s past as he reads her diary in a hotel room. Flashbacks reveal a young woman’s political activism, and romantic escapade, to the viewer and the husband at the same time.

Fereshteh’s early past, which she had successfully kept as a secret from her husband, contrasts with the peaceful setting of the early scenes. Surprisingly, the unraveling story reveals the protagonist’s oppositional stance to the prevailing revolutionary ideology, and most important it places her in opposition to the ideology of the government that her husband represents. The Hidden Half’s flashbacks are preceded by a visual shot of a mirror, which captures the meditative mood of its object, the protagonist, while offering an introspective mood into the past. In a way, the mirror image preceding the flashbacks reinforces the significance of the impact of the past event and its unsettling effect in the present.

In terms of its historical setting, this film takes place during the emergence of the reformist government of Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005), whose civil society platform provided a rare glimpse of hope and aspiration for those with divergent political points of view. The presidential judge, played by the late Atilla Pesiyani, is an active and conscientious representative of the reformist government. By assigning him to hear the appeal of a female prisoner in Shiraz, the judge represents the reformist government’s endeavor to right many wrongs. Ironically, the present dilemma—the last requests of a prisoner on death row—is directly linked to a silent past, which has now come to haunt them. As such, the national crime of the past adopts a new political meaning in the reformist platform of the present historical period. In the autobiographical letter to her husband, Fereshteh pleads for understanding and compassion, to judge not based on prejudices and biases, but rather judiciously, as one would expect from a reformist government’s judge. This is a call for sympathy and compassion, partly because by revealing to him the similar past shared between her and the political prisoner, Fereshteh is expressing the possibility of a second chance that the political prisoner has been denied, and according to Fakhreddin Azimi, “rekindling her submerged political commitment through her attempted intervention on behalf of the woman prisoner may make the past—the struggles, loves, passions, risks—worthwhile if it could save a life in danger of being wasted by the moralistic but ethically indifferent quasilegal and bureaucratic banalities that had destroyed or maimed so many lives in the past.”1Azimi, Fakhreddin. 2011 The Hidden Half (Tahmineh Milani): Love, Idealism, and Politics in Josef Gugler, ed. Film in the Middle East and North Africa: Creative Dissidence. 63-73 Austin: University of Texas, Austin. 72 As a representative of justice in a government that claims purity as well as a pluralist platform, he is certainly responsible to listen attentively and to judge judiciously.

In juxtaposing the present dilemma with past political events, the film reviews, and in the process reevaluates, the early revolutionary years, in which left-leaning political factions became outcasts in the newly established Islamic state. In the revolutionary past, this political activism led to the arrest and execution of hundreds of supporters and sympathizers of left-leaning organizations. From young Fereshteh’s outerwear, a trench coat and wide pants, the viewer extrapolates an inclination to one of the guerrilla factions of early revolutionary years, perhaps she was a sympathizer that not only distributed pamphlets and tracts but expressed readiness to take up arms to fight their opponents.

Fereshteh’s husband learns of her story not directly from her but in the silent process of reading her diary in a hotel room far from home, in the filmic form of a voice-over and multiple flashback scenes. It is Fereshteh’s voice from within the isolated hotel room, along with images, that narrates her life, her past, and the events that not only affected her “self” but impacted revolutionary Iran. The diary narration shows how she managed to overcome the odds, despite all political hurdles, and found refuge in an old lady’s house—a woman who later became her mother-in-law—whereas the rest of her classmates were destined to ill fate, as some were arrested, some fled into exile, some were sentenced to death by revolutionary courts, and some were executed. From the very outset, the juxtaposition of the imprisoned woman’s life, who seeks justice now with that of the free Fereshteh leaves room for reflection, reassessment, and reevaluation of the historical events that led to the events.

Especially significant in the course of the events is that Fereshteh’s initial plea for justice in the beginning of her autobiographical account merges at the end of the film with the same voice with which we hear the chador-clad female prisoner plea her case. This overlapping identical voice reiterates the common collective pain and suffering (dard-e moshtarek, in the words of Ahmad Shamlou) that Fereshteh insists on highlighting, emphasizing the indispensable necessity of a chance for life. By paralleling her own life with that of the female political prisoner, she prompts her husband to rethink and reevaluate the death sentence, hoping that he may draw parallels between his wife’s trajectory and the possibilities of the political prisoner’s reform. What would he do if his wife was sitting in front of him narrating her own life –instead of this girl? What if his wife did not have this chance if she had been arrested at the time and had to spend her entire life in political prisons? Azimi believes that “she writes her memoir to reveal to her unsuspecting husband the carefully subsumed secrets of her earlier life. The act of revisiting and revealing the tormenting, unforgettable emotional-political entanglements of her past is not merely intended for personal expiation—an act of self-revelation, a moment of catharsis, a form of healing confession. Fereshteh seeks to distance herself from the past altogether and to persuade her husband to try to understand why she and those like her acted as they did in their youth.”2 Ibid 71. While Fereshteh distances herself from the past, she also revisits it with a nostalgic sense, and most important, by recasting her past, she strategizes to dismantle preconceived notions about her political engagement and offers a chance to advance a political discourse that is suppressed and inhibited.

ronically, The Hidden Half calls for a reevaluation of the idealistic past by featuring archetypal characters. For instance, Mr. Rastegar, the main antagonist to Fereshteh throughout her years of study, represents the Islamic radical ideologues, who confidently took the lead in purging universities from dissidents in the process of a “cultural revolution” that closed academic institutions in Iran from 1981–1984. In this three-year period, figures like Rastegar (that translates as salvation), whose allegiance to a seemingly puritan Islamic ideology prevailed, gained control over academic institutions, trying to Islamize faculty and the student body as well as the content taught in humanities and social science programs, purging faculty and students whose adherence to the revolutionary ideology was dubious. In the latter part of the 1980s, these ideologues consolidated their control at Iranian universities through the Anjoman-e Eslami (The Islamic Society) and the official Harasat (The Security/Intelligence Office). In this process, they attempted to ensure that non-Islamic ideological strands and small organizations or factions would not reappear at universities and that they would establish an Islamized version of interaction and discourse throughout the academic setting. Rastegar represents this Islamizing apparatus that oversees the academic setting ensuring that the religious and ideological value system remains intact.

Milani also creates the archetype of the reformist judge, who is open for reform and change. In the judge’s character, the viewer notices a gradual evolution, which develops in the process of reading his wife’s life story. Earlier on, the judge seems to have a collegial relationship with Rastegar, but there is an attitude shift when Rastegar calls him from downstairs (presumably to tell him his own version of the story). The judge stands him up and continues to read his wife’s letter diary. Finally, in the last scene with the female political prisoner, the judge dismisses Rastegar, much to his chagrin. The fact that the director creates a character who evolves in the course of the film characterizes the reformist era’s change and reform platform that seeks to reevaluate the past and reconsider some of the early revolutionary and radical decisions of the early years.

In the same way as Rastegar and the judge, Javeed’s character is archetypal. It is through flashbacks that the viewer learns about the protagonist’s love affair with a middle-aged man called Javeed (translated as the eternal one), and thus a window is opened to learn about political activism in Iran. Azimi describes Roozbeh Javeed as “a man with a certain mystique,” who possesses “a seemingly stoic serenity, a self-confidence born of wealth and status, an impeccable if affected elegance, a conspicuously cosmopolitan deportment.” Azimi continues to say that Javeed’s “gentle, discreetly reassuring voice gives him a particularly appealing presence” and “a certain gravitas.”3Azimi 66. However, the film remains vague about the origins and wealth of Javeed and in fact questions his background at times, as Javeed himself questions the import of origin and wealth in one of his public speeches at the outset of the revolution. It is through the account of the woman who claims to be his wife that we understand Javeed’s staunch support of the Iranian communist party, The Toudeh. However, he keeps silent about this past activism, which leaves room for further conjecture and assumptions that add to the general ambiguity of the film and yet allow the viewer to define the man’s character irrespective of his political affiliations. At the same time, Javeed is the editor of the ‘Science and Industry’ weekly and is in constant contact.

With contemporary scholars and literati, who converse with him and pay him regular visits at the office. This is the intellectual class that has adopted a different approach from the early revolutionaries, a class that promotes and encourages reading and increasing knowledge and awareness of one’s own culture, political, and historical background rather than regurgitating what one political activist leader transmits as the right and true way of resistance. In other words, the political being who had acted perhaps rashly in his youth and participated in militant political activity has now adopted a new approach to reach his ideals, namely, through science and industry.

Rouzbeh Javeed creates the link between the aristocracy and the everyday classes when he proposes to take Fereshteh to England and to live with her in an environment in which they will be treated in an egalitarian manner. When the viewer learns of Javeed’s marriage to an eye-twitching, stuttering, limping wife (or ex-wife), who represents aristocracy, and finds out about his earlier leftist activism, Fereshteh’s love is framed within an uncanny love triangle, where Fereshteh seems to have been mistaken for Javeed’s first love, Mahmonir, a woman of striking resemblance to Fereshteh, who disappeared during the 1953 social movement.

What is significant about Javeed is that he never ages. When he re-appears at the end of the film after twenty years, he looks exactly the same as before. Rouzbeh Javeed’s mere presence creates a historical continuity between Iran’s social movements, from 1953 to 1979 and again from 1979 to 1999, and at the same time forges a link between the aristocratic and the everyday classes. Javeed’s static composure throughout the film, between his 1979 to 2000 stature is evident that the director depicts him as an archetypal representative of a particular generation of Iranians, which differentiates him from the other main characters in The Hidden Half, who each represent a different generation in Iran’s historical and political past. Furthermore, Javeed’s presence in the film evokes the collective memory of the 1953 coup, the process of the toppling of a prime minister who had championed the cause of Iran in international settings but was overthrown—with the help of American and British intelligence operatives in the course of a successful coup. Thus, there is a rather direct connection between this collective memory and the Iranian Revolution of 1979 as well as the reformist movement of 1997.

Mr. Rastegar, the early Hezbollahi, represents fear and radical dogmatism, as he follows Fereshteh’s life from her early college years to her married life. He is an essential figure in demonstrating the senseless radical pursuit of early Islamic revolutionaries. Earlier in the film, in a flashback, we see the young Fereshteh rushing back into Rouzbeh Javeed’s Range Rover (itself a symbol of wealth and prestige in the beginning years of the revolution) after seeing the revolutionary guards at her doorstep at the end of the alley. The scene effectively expresses the fear that Fereshteh experiences upon seeing the guards. These revolutionary guards, who had presumably come to arrest her, represent a dogmatic system that viewed an eighteen-year-old college student as a threat. They represented a system that arrested its young and restless and put them on death row as in the imprisoned woman in Shiraz. While Mr. Rastegar did not succeed in arresting Fereshteh or stopping her academic studies, the film succeeds in demonstrating the fear associated with his archetypal character as he reappears throughout various scenes and in different historical periods, and each time inciting more fear.

In addition to Rastegar, other fear-inciting characters manifest themselves throughout The Hidden Half, such as famous, or infamous, radical figures, militants, revolutionary guards, and self-made vigilantes like Zahra Khanum, the incomprehensible lady thug that started a witch-hunt campaign on Tehran University’s campus following the Islamic revolution. To the astonishment of many, Zahra Khanoom, a real-life figure who opposed the political students in very rudimentary ways with sticks and fists, is represented for the first time in the postrevolutionary film in The Hidden Half. Zahra Khanoom, who up to this day is casually referred to as a ruthless radical and an irrational revolutionary, is for the first time represented in a serious light. In the Zahra Khanoom scenes, she is accompanied by revolutionary guards, known as “komitehiis,” who hunt down the dissident voices on the streets of Tehran. In early revolutionary years, these revolutionary guards picked fights with peaceful student information stands at institutions of higher education, followed political activists dispersing political flyers, and ultimately arrested dissident students. In short, they created an atmosphere of fear for all those who had any political or social affiliations to leftist-oriented groups.

Social Class and Generational Gaps

Fereshteh’s social class also affects her decision-making process, as she comes from a provincial background, the fifth child of a family with thirteen children, and she has not had the same experiences as her other Tehrani friends. Upon her arrival at Tehran University during the first year of the Iranian revolution, the various leftist political groups who had also been active participants in the revolution had already started clashing with the Islamic forces, and this provincial young woman is thrown into the midst of the revolutionary fervor.

Toward the end of the film, the plot’s direction is complicated even further with a twist. Tahmineh Milani’s narration of a woman’s life some twenty years after the Iranian revolution, thus, is contextualized within its historical, social, cultural, and political background in order to relay a sense of a collective past that needs to be appropriately understood, analyzed, and taken as a lesson for future progress. Subversively, in a coded language, Tahmineh Milani shows a sympathetic view toward political activists and participants in the Iranian revolution, who were later arrested and some of whom were executed.

As a first attempt by a postrevolutionary Iranian director to treat a sensitive subject matter such as the role of different leftist groups in early revolutionary uprisings, it did not take long for the government to charge Milani with treason and threatening national security. So even twenty years after the revolution, although such a reevaluation of the past is not only necessary but mandatory, her treatment of the subject matter raised eyebrows. To a great extent, The Hidden Half presents a semiautobiographical account of the female filmmaker, Tahmineh Milani, who, like Fereshteh, began as a political activist in college and subsequently experienced persecution for that. It was during the early years of the revolution that left-leaning political factions turned in outcasts to the newly established Islamic state, leading to the arrest and execution of hundreds of their supporters and sympathizers. 4Scott, Stephanie. 2001 Tahmineh Milani Talks Back: A Feminist Filmmaker Forges Ahead and Fights for Freedom in Iran.www.New England Film.com. Fereshteh’s early stand, as a supporter of a guerilla faction in the early revolutionary years, exudes a certain naiveté and simplicity but at the same time a fervor and passion for a cause that was universal and praiseworthy. It was this idealism that attracted many to her, including Roozbeh Javeed. Resembling in many ways Makhmalbaf’s A Moment of Innocence, The Hidden Half calls for a reevaluation of the idealistic past, posing critique but at the same time narrating the incidents of a past that has remained unheard and stories that were untold as a result of the subsequent repression.

While the questions the film poses remain crucial in understanding the historical period, by such a critique, but the message that early revolutionary purges could have been flawed is certainly one that the revolutionary Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance (MCIG) did not tolerate. 5Also see Azimi. The film was designated as seditious and banned shortly after its release, with Milani arrested and jailed by Iran’s judiciary and accused of “abusing arts as a tool for actions to suit the taste of the counterrevolutionary and mohareb [those who fight god] grouplets.” Tahmineh Milani’s sympathetic treatment of dissident organizations and political prisoners was deemed as supportive of their oppositional political stance. [mfn]Hamid Mazra’eh. 2001 Fereshteh haye Sukhteh: Naqd va barresiye film haye Tahmineh Milani. Tehran:Varjavand. [/mfn] But Tahmineh Milani knew of the politically sensitive project she was embarking upon, and in an interview with the World Socialist Website (WSWS), she confirmed that, “With the Hidden Half, I understood that it could lead to my arrest and imprisonment, but I was an established director and felt it was my duty to make this film. I had to do it for all those who had been exiled or killed.”6 See “Iranian filmmaker faces death penalty in upcoming trial.” Iranian director Tahmineh Milani speaks with WSWS, By Richard Phillips 29 September 2006. http://www.wsws.org/articles/2006/sep2006/mila-s29.shtml After renowned international filmmakers, such as Francis Ford Coppola, Oliver Stone, and others, wrote letters on her behalf, she was freed after a week of incommunicado arrest. Eventually, after several months of legal tension for her family, the charges were dropped. [mfn]Ibid.[/mfn]

Fereshteh’s Notion of Past and Justice

Like all the other characters discussed here, Fereshteh too represents an archetype of political activist women, who saw the world from a certain angle. With the revelation of her past ideological inclination, the viewer and the husband find out about the female protagonist’s political stand, and its inherent opposition to the very government the judge/husband represents, at the same time. But the taking power of the reformist government represents a glimpse of hope, and it is this new hope that prompts Fereshteh to reveal her story and to ask her husband to judge not based on hitherto ideological clichés and narrow-minded conclusions, but rather on account of facts and life trajectories as her own.

Fereshteh’s Notion of Past and Justice

Like all the other characters discussed here, Fereshteh too represents an archetype of political activist women, who saw the world from a certain angle. With the revelation of her past ideological inclination, the viewer and the husband find out about the female protagonist’s political stand, and its inherent opposition to the very government the judge/husband represents, at the same time. But the taking power of the reformist government represents a glimpse of hope, and it is this new hope that prompts Fereshteh to reveal her story and to ask her husband to judge not based on hitherto ideological clichés and narrow-minded conclusions, but rather on account of facts and life trajectories as her own.

The voice narrating the past events belongs to Fereshteh. This voice is not only the protagonist’s voice, but it is also the voice of revolutionary Iran as well as the voice of the female prisoner in Shiraz. As mentioned earlier, there are clear links established between Fereshteh and the chador-clad, face-less woman pleading her case to the judge in an isolated prison office. This woman’s story starts with exactly the same words as Fereshteh’s, as well as the same dramatic voice. By creating this unmistakable link between the female protagonist and the female prisoner, Milani questions the rationality of arresting and imprisoning young early revolutionaries, holding them for over two decades, and handing them down life sentences. The film is thus a cogent critique of the justice system, but she also critiques the judgmental traits of humans. At the end of the film, at a coincidental meeting between Fereshteh and Javeed after twenty years, the former admonishes Fereshteh for her briskness to judge before knowing all the facts.

The film ends with a number of ambiguities, as it is unclear why Javeed admonishes Fereshteh for her rashness in judgment. Had the ex-wife of Javeed deceived her when she recounted Javeed’s early marriage, or had she merely represented a different version of the truth? Were there other facts that could have changed her opinion about leaving with Javeed for London twenty years earlier? We also do not know what the fate of the female prisoner will be. Did the diary affect the decision of the husband/judge in any way or form? Was her life sentence commuted, or carried out?

The film’s ending remains oblique, and the viewer leaves not knowing the outcome of Fereshteh’s revelations and their possible impact on the life of the female prisoner. It is exactly the existence of such final ambiguities that opens up space for reflection, for thinking of the critical notions of justice, judging and being judgmental, and the crucial role of judges in contemporary Iran.

Conclusion

Ah…

This is my share

This is my share

my share is the sky that a hanging veil takes it away from me

my share is descending isolated stairwells

and to be dispatched to exile and ruin

my share is a tragic leisurely walk in the garden of memories

and transpiring in the sadness of a voice that says

“I love your hands.”

(Forough Farrokhzad)

In The Hidden Half, we encounter women who have struggled for self- expression, for achieving their goals and their ambitions. In the course of this struggle, they construct a negotiated identity, which situates them in a liminal space. This liminal space is neither concrete nor preestablished but conditioned on historical circumstances, individual exigencies, and social norms and values, and it certainly is rather fluid and dynamic. The ambiguous ending of the film and the multiple layers of meaning that is worked through the film leave room for a multilayered interpretation that undermines the status quo and points to a fragmented subjectivity. The contrastive discourse that juxtaposes peace and harmony against conflict and disharmony underscores and problematizes women’s subjectivity and identity by throwing the focus on their social, cultural, and psychological dilemma. The Hidden Half exposes a narrative that has remained hidden from the public and untold to future generations. This narrative also demonstrates how women in post-revolutionary Iran struggled to negotiate their various identities, sometimes at the cost of hiding, or even killing, the personal, social and political desires. As Ziba Mir-Hosseini has explained this situation as “younger voices demanding personal freedom and questioning the whole notion of feqh-based gender relations. These voices are heard in films that deal openly and critically with gender roles and have love as their main theme.”7Mir-Hosseini, Ziba. 2001. Iranian Cinema: Art, Society and the State. Middle East Report 229 (Summer): 26-29.

We encounter how women’s identities are established within this bifurcated space, where harmony and chaos coexist. Like Fereshteh, many Iranian women seek to make sense out of the complexities and contradictions of urban life, where their identity is predicated on how they succeed in overcoming social, political, and cultural obstacles facing their everyday lives. In this vein, their identities gain meaning based on a composite construct that society and women themselves have identified as acceptable, but it is also the result of a constant negotiation that takes place in the wake of the steady societal changes that occur, mostly despite them rather than with them. In The Hidden Half, we see a woman in midlife, reevaluating her life and questioning the quality of their past.

In The Hidden Half, this re-evaluation of the past is no longer a personal and individual necessity, rather this revelation and reevaluation could lead to reversing of a life sentence . The judgment in the film can only be informed by the revelations of a feminine past, which have direct impact on the present, and illustrates how Iran’s past revolutionary ideology has a direct impact on the protagonist’s present life and how it has contributed to the liminal space.