The Horror Genre in Post-Revolutionary Iranian Cinema

Figure 1: Poster for the film Under the Shadow (Zīr-i Sāyah), directed by Bābak Anvarī, 2016.

Introduction

Films of any given genre will inevitably reflect the cultural, political, and social contexts of their time. Moreover, the development of each genre is closely connected to the changes occurring in a society over time, and this is certainly the case for horror. According to Brigid Cherry, the films in this genre “meaningfully address contemporary issues and reflect cultural, social or political trends.”1Brigid Cherry, Horror (New York: Routledge, 2009), 11. Thus, films in the horror genre can serve as mirrors of societal anxieties across different periods, and the evil they depict can be read as representing a culture’s collective fears.

A historical analysis of horror, from its inception with James Searle Dawley’s 1910 film Frankenstein to the present, suggests that its enduring presence is rooted in its ability to adapt and reflect the social concerns of different eras. As Cherry states, since “fear is central to horror cinema, issues such as social upheaval, anxieties about natural and manmade disasters, conflicts and wars, crime and violence, can all contribute to the genre’s continuation.”2Brigid Cherry, Horror (New York: Routledge, 2009), 11. Cherry, in an effort to articulate the reciprocal relationship between horror genre films and political-social transformations, as well as the underlying anxieties of each period, presents the concept of the “limited experience of fear.” Referencing Isabel Pinedo, she writes that “such films are thus cathartic, allowing for these anxieties and other negative emotions towards the world or the society one inhabits to be released safely.”3Brigid Cherry, Horror (New York: Routledge, 2009), 12. Further elaborating, Cherry asserts:

And, of course, horror cinema can also represent more personal fears and phobias, which are ever present, and thus act to confront or release those fears on a psychological as well as a social level. We can thus see horror cinema as fulfilling a basic human need—for society and for the individual.4Brigid Cherry, Horror (New York: Routledge, 2009), 12.

Thus, one of the primary reasons for creating horror films is that audiences confront their personal fears and anxieties within the safe confines of the cinematic experience. This article aims to explore the reflection of societal anxieties in post-revolutionary Iranian horror cinema, with the goal of examining how these films engage with political and social transformations across different periods. The significance of this research lies in the fact that Iran has undergone fundamental changes over the past fifty years—including a revolution and an eight-year war—which can be reflected in the themes and production of Iranian horror films. This analysis is conducted using the theoretical framework of English film critic Robin Wood (1931-2009). His proposed model has proven effective in categorizing the societal anxieties reflected in American horror films, thereby offering a framework that can be extended to the horror cinema of other countries, including Iran.

In “The American Nightmare: Horror in the 70s,” Wood draws on Sigmund Freud’s theory of the “return of the repressed” and its manifestation in the concept of the “Other,” ultimately identifying a distinct Freudian pattern in 1970s American horror films. Wood argues that the monster in these films serves as a reflection of the fears and anxieties of a society that, through the mechanism of “repression,” has relegated these fears to the unconscious. These repressed elements are then reintroduced and represented in the form of the “Other,” embodied by the “monster.” Wood distinguishes between eight types of the “Other”:

Quite simply, Other people, Woman, The proletariat, Other cultures, Ethnic groups within the culture, Alternative ideologies or political systems, Deviations from ideological sexual norms—notably bisexuality and homosexuality, Children.5Robin Wood, Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan…and Beyond (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 68.

He classifies the monsters of horror films into various forms of “otherness” to clearly demonstrate the reciprocal relationship between horror cinema and relevant socio-political transformations of the era. By emphasizing this perspective on horror films, Wood argues that his theory provides a framework for a more rigorous and committed engagement with the genre.

With this background in mind, this article first offers a clear definition of the horror genre and then examines two notable Iranian horror films—The 29th Night (Shab-i bīst u nuhum, 1989) by Hamīd Rakhshānī, and Under the Shadow (Zīr-i Sāyah, 2016) by Bābak Anvarī—as fairly successful examples that fit within Wood’s theoretical framework. In analyzing these two key films, along with several other Iranian horror films, this article also seeks to answer the following questions:

1.How can horror films reflect a society’s collective anxieties? 2. How do post-revolutionary Iranian horror films align with Wood’s theory of the “return of the repressed” and his concept of “the Other”? 3. How do The 29th Night and Under the Shadow create fear by reflecting social and political changes, as well as common beliefs, of Iranian society? 4. And finally, why are films that directly address a society’s political and social anxieties more frightening and impactful?

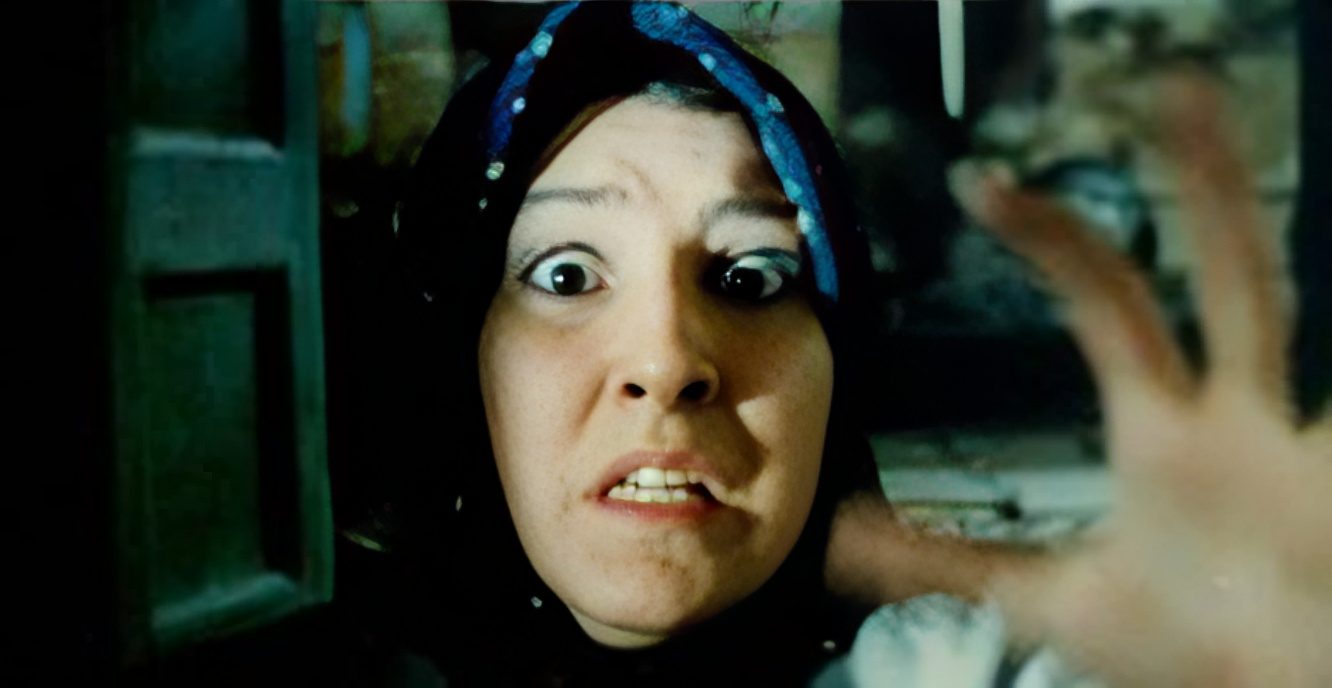

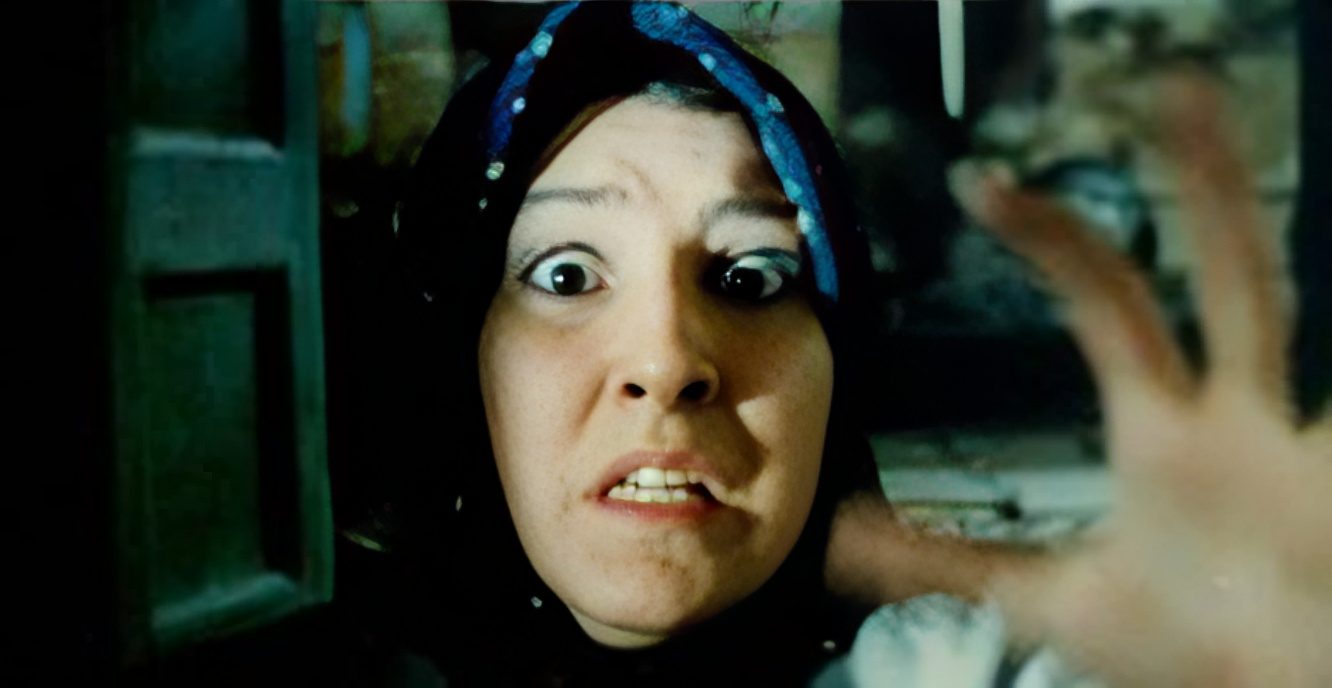

Figure 2: A still from the film The 29th Night (Shab-i bīst u nuhum), directed by Hamīd Rakhshānī, 1989.

Theoretical Observations

Wood begins by acknowledging that his theoretical framework is grounded in the concepts of “repression” as articulated by Freud, and the “return of the repressed” as proposed by Herbert Marcuse, the German sociologist.6Robin Wood, Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan…and Beyond (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 63. As a result, his theory is consistent with the psychoanalytic approach to horror films. Freud defines the concept of the “repressed” in the opening of an article by the same title as follows:

One of the vicissitudes “an” instinctual impulse may undergo is to meet with resistances which seek to make it inoperative. Under certain conditions, which we shall presently investigate more closely, the impulse then passes into the state of “repression.”7Ivan Smith, ed. Freud: Complete Works (open-access pdf, 2010), 2977.

From Freud’s perspective, repression occurs when a gap is created between the conscious and unconscious. He argues that repression prevents certain drives or desires from reaching the conscious mind.8Ivan Smith, ed. Freud: Complete Works (open-access pdf, 2010), 2978. Freud further asserts that these repressed desires never disappear:

The doctrine of repression, which we need in the study of psychoneuroses, asserts that such repressed wishes still exist, but simultaneously with an inhibition which weighs them down. The psychic mechanism which enables such suppressed wishes to force their way to realization is retained in being and in working order.9Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams (New York: Avon. 1980), 94.

In an article focusing on aesthetics, in which he analyzes works such as E.T.A. Hoffmann’s The Sandman, Freud defines the concept of “the uncanny” as follows:

It is undoubtedly related to what is frightening─ to what arouses dread and horror; equally certainly, too, the word is not always used in a clearly definable sense, so that it tends to coincide with what excites fear in general.10Ivan Smith, ed. Freud: Complete Works (open-access pdf, 2010), 3675.

Figure 3: An illustration for The Sandman, a short story by E. T. A. Hoffmann.

He further asserts that “the uncanny” is directly linked to the repressed, with strange and unnatural phenomena serving as manifestations of repressed desires or memories that have returned to consciousness.11Ivan Smith, ed. Freud: Complete Works (open-access pdf, 2010), 3676. According to Freud’s theory, what evokes the feeling of “the uncanny” and an unnatural sensation in humans is not something entirely unknown. Rather, it is something that appears to be unknown but was repressed into the unconscious long ago. Therefore, in Freud’s model, these experiences, drives, and thoughts continually threaten to resurface in the conscious mind, and this phenomenon is nothing other than the “return of the repressed.” Freud argues that these repressed elements can resurface in the form of hallucinations and dreams, and may also give rise to phobias, fears, and anxieties.12Brigid Cherry, Horror (New York: Routledge, 2009), 104.

Drawing on Freud, the German philosopher and sociologist Herbert Marcuse divides the repression of natural instincts and drives into two categories: basic repression and surplus repression. Basic repression is linked to the development and advancement of humanity, while surplus repression refers to the repression of desires and behaviors deemed unnecessary but required for social control and domination.13Horowitz, Gad. Repression – Basic and Surplus Repression in Psychoanalytic Theory: Freud, Reich and Marcuse (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1977), 2. Basic repression is a prerequisite for civilization and the peaceful coexistence of human beings. As Wood states: “It is what makes possible our development from an uncoordinated animal capable of little beyond screaming and convulsions into a human being.”14Robin Wood, Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan…and Beyond (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 63. In contrast, surplus repression is specific to cultures and varies significantly from one civilization to another.

Before introducing his proposed framework for horror films, Wood first addresses the differences between these two forms of repression. To differentiate between the two types of repression, he draws on examples from American culture:

Basic repression makes us distinctively human, capable of directing our own lives and co-existing with others; surplus repression makes us into monogamous heterosexual bourgeois patriarchal capitalists (“bourgeois” even if we are born into the proletariat, for we are talking here of ideological norms rather than material status)—that is, if it works.15Robin Wood, Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan…and Beyond (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 64.

He also addresses the revolt against these two forms of repression, asserting:

Basic repression (universal, necessary to any form of civilization) and surplus repression (specific to each culture, varying enormously in degree from one culture to another), the two levels being continuous and interactive rather than discrete. The revolt against repression may then be valid or invalid, a legitimate protest against specific oppressions or a useless protest against the conditions necessary for society to exist at all, the two not being easily or cleanly distinguishable.16Robin Wood, Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan…and Beyond (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 42.

Subsequently, Wood distinguishes between the concept of “repression” and that of “oppression.” He considers repression to be an internal process, as it is linked to the unconscious. He then explains a form of repression that is primarily external, referring to the ideological confrontation between governments and individuals, before raising a key point: “What escapes repression has to be dealt with by oppression.”17Robin Wood, Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan…and Beyond (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 64. As a result, Wood establishes a reciprocal relationship between “the return of the repressed” and external repression, arguing that the foundation of his theory on horror cinema rests on the idea that the monsters in horror films serve as manifestations of repressed matters that have resurfaced in monstrous form. He describes the “true subject” of the horror genre as:

… the struggle for recognition of all that our civilization represses or oppresses, its re-emergence dramatized, as in our nightmares, as an object of horror, a matter for terror, and the happy ending (when it exists) typically signifying the restoration of repression.18Robin Wood, Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan…and Beyond (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 68.

What complements the concept of “the return of the repressed” in Wood’s theory is the notion of the “Other.” Cherry succinctly presents selected definitions of the “Other” as outlined by Edward Said and Jacques Lacan:

The Other is central to definitions of identity since it is anything that is outside of or different from the self or the society. Edward Said (2003), for example, explored how Western societies Othered the people of the ‘Orient’ in order to control and subjugate them. Jacques Lacan (1998) introduced the idea of the Other in his account of language and symbolic order. In very simple terms, the Other is that which is separated off from ourselves by subjectivity (we are only created as subjects in relation to the Other and for Lacan desire is always of/for/by the Other – so perhaps we can see why the monstrous Other of horror cinema is so fascinating).19Brigid Cherry, Horror (New York: Routledge, 2009), 107.

Wood discusses the concept of the ‘Other’ as follows:

Otherness represents that which bourgeois ideology cannot recognize or accept but must deal with in one of two ways: either by rejecting and if possible annihilating it, or by rendering it safe and assimilating it, converting it as far as possible into a replica of itself.20Robin Wood, Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan…and Beyond (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 65.

We will now briefly outline eight aspects of the “Other” according to Wood’s theory.

1.Other People

Wood believes that in a capitalist system, concepts such as power, domination, and control extend to human relationships. One of the relationships he emphasizes is the marriage between a man and a woman. He states that, according to American capitalist culture—similar to the prevailing marriage culture in Iran—“marriage as we have it is characteristically a kind of mutual imperialism/colonization, an exchange of different forms of possession and dependence, both economic and emotional.”21Robin Wood, Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan…and Beyond (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 66.

2.Women

Wood believes that in a system of domination, particularly in a patriarchal one where the power of most social institutions lies in the hands of men, women occupy an inferior position that meets the criteria of the concept of the “Other.”22Robin Wood, Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan…and Beyond (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 66. Under male domination, women lose their autonomy and independence. Men, in turn, repress or reject traits considered feminine, projecting these repressed qualities onto women to undermine their status.

3.The Working Class

The working class serves as a useful means for the capitalist system in terms of exploitation and oppression. Wood also believes:

The bourgeois obsession with cleanliness, which psychoanalysis shows to be an outward symptom closely associated with sexual repression, and bourgeois sexual repression itself, find their inverse reflections in the myths of working-class squalor and sexuality.23Robin Wood, Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan…and Beyond (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 67.

4.Other cultures

According to Wood, when other cultures come into proximity with American culture, there is a tendency to either suppress them or reshape them to align with our values. To illustrate this point, he references John Ford’s dualistic portrayal of Native Americans in his film Drums Along the Mohawk (1939):

If they are sufficiently remote, no problem arises: they can be simultaneously deprived of their true character and exoticized (e.g., Polynesian cultures as embodied by Dorothy Lamour). If they are inconveniently close, another approach predominates, of which what happened to the American Indian is a prime example. The procedure is very precisely represented in Ford’s Drums Along the Mohawk, with its double vision of the Indians as “sons of Belial” fit only for extermination and as the Christianized, domesticated, servile, and (hopefully) comic Blueback.24Robin Wood, Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan…and Beyond (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 67.

5.Ethnic communities within a culture

Wood regards culturally distinct groups—such as African Americans, Native Americans, other racial minorities, and the working class—as tools employed by the capitalist system onto which it projects its own values. If they refuse to function as such instruments, they are left with two options: either to remain on the margins without disrupting the dominant order, or to emulate dominant values and behaviors, thereby becoming a version of the “good bourgeois.” This resembles the case of Pakistanis who, by adopting Western attire such as the business suit, become more readily accepted within dominant cultural or social frameworks.25Robin Wood, Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan…and Beyond (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 67.

6.Alternative ideologies and political systems

According to Wood, Marxism represents the most significant ideological challenge to the capitalist system. For this reason, despite the significance of this theory, Marxism is deliberately disregarded in the capitalist system of public education due to the constant fear that it could potentially challenge the dominant capitalist ideology. He adds that “Marxism exists generally in our culture only in the form of bourgeois myth that renders it indistinguishable from Stalinism.”26Robin Wood, Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan…and Beyond (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 67.

7.Deviations from Ideological Norms in Sexual Relations: Bisexuality and Convergence

Homophobia, defined as an irrational fear and hatred of homosexuality, manifests as a psychological process of repression and the failed projection of repressed bisexual tendencies onto others. The mainstream hatred towards this form of “Otherness” is essentially the result of these tendencies being repressed within the individual.27Robin Wood, Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan…and Beyond (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 67.

8.Children

Wood identifies children as the most repressed segment of the population. “What the previous generation repressed in us, we, in turn, repress in our children, seeking to mold them into replicas of ourselves, perpetuators of a discredited tradition.”28Robin Wood, Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan…and Beyond (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 68. He categorizes this group based on their depiction in American horror films of the 1960s and 1970s.

In Iranian horror films, monsters often take the form of one of the above-mentioned “Others.” In some Iranian horror films, the lack of a clear political or social context weakens the monster’s impact, making it harder for the audience to connect with it. In other words, it is not anchored in the real-world issues or fears that could render it more frightening, and more meaningful, to the Iranian audience. Although the monster appears to emerge from the “return of the repressed,” embodied as an “Other,” this figure sometimes fails to serve as a reliable representation of societal anxieties. Instead, the monster is reduced to a disposable figure, crafted solely for the purpose of entertaining through the act of frightening the audience, and, at times, even fails to achieve this effect.

To categorize Iranian monsters within Wood’s framework of the “Other,” it is necessary to selectively examine examples that align with the cultural context of Iran. The most significant group of “Others” in Iranian horror cinema is “women.” It can be said that in almost every Iranian horror film, we can find the trace of a female victim. Women in Iran—historically shaped by traditional and patriarchal attitudes—have been systematically deprived of their agency. The repression of feminine traits in men has also relegated women to a subordinate status in society.

In Iranian horror cinema, women typically appear in two forms. The first and more common form is that of the female victim. In this case, the monster of the film often attacks a woman. The second form, which is less common, is the monstrous woman. According to Wood, the repressed element in women can take the shape of a monstrous figure, attacking the patriarchal system and establishing its presence. We will discuss the role of women as the “Other” in each of these two categories. It is worth noting that while women are the most common examples, the working class, individuals with alternative ideologies, and children also appear as “Others” in Iranian horror films.

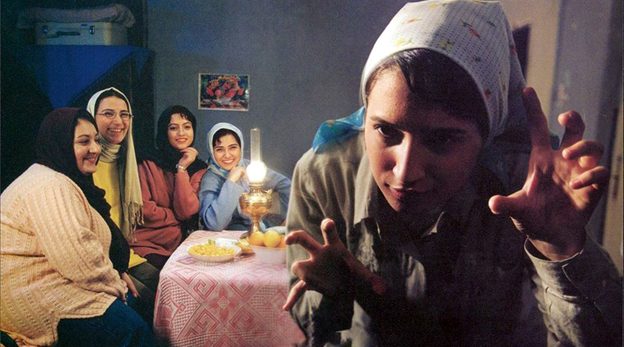

Figure 4: A still from the film Girls’ Dormitory (Khābgāh-i Dukhtarān), directed by Muhammad Husayn Latīfī, 2004.

Wood also introduces an important element in the creation of monsters in American horror films, which is relevant for analyzing Iranian examples. Among the themes of the horror genre, such as the psychotic or schizophrenic individual, nature’s revenge, demonic possession, the child, horror and cannibalism, Wood identifies a unifying element: “the family.” The relationship between the family and the horror genre is such that even the psychotic or schizophrenic individual, the Antichrist, and the child-monster are viewed as products of the family—regardless of whether the family is responsible in their creation.29Robin Wood, Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan…and Beyond (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 75.

The traditional family plays a significant role in the creation of monsters in many Iranian horror films. Thus, the family, along with various forms of the “Other,” plays a crucial role in horror cinema and serves as a significant source of fear. We will now turn to key horror films in Iranian cinema, categorizing each type of monster within the concept of “Otherness” and discussing their political and social roots.

Figure 5: A still from the film Girls’ Dormitory (Khābgāh-i Dukhtarān), directed by Muhammad Husayn Latīfī, 2004.

Research Background

Zahra Khosroshahi argues that two Iranian horror films, A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014) and Under the Shadow (2016), employ elements of the magical and the monstrous to explore issues of femininity in diasporic Iranian horror cinema.30See Zahra Khosroshahi, “Vampires, Jinn and the Magical in Iranian Horror Films,” Frames Cinema Journal 16 (Winter 2019), https://framescinemajournal.com/article/vampires-jinn-and-the-magical-in-iranian-horror-films/ Khosroshahi points out similarities between these films, such as using the veil as a symbol of female figures and their connection to the magical and the monstrous, as well as using grotesque magical female figures to explore the limits and possibilities for women. She also discusses the theme of hybrid identity in A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night and the concept of “in-betweenness,” based on Homi Bhabha’s theory of “the third space,” in the film Under the Shadow.

Pedram Partovi analyzes the representations of popular Muslim belief and practice in modern Iran by focusing on the horror film Girls’ Dormitory (Khābgāh-i Dukhtarān, 2004), where the “horror” is rooted in the concept of the jinn.31See Pedram Partovi, “Girls’ Dormitory: Women’s Islam and Iranian Horror,” Visual Anthropology Review 25 no. 2 (Fall 2009), 186-207. He examines how the female character’s encounter with a jinn contrasts with mainstream religious views, which often attribute belief in such supernatural phenomena to the perceived mental or emotional weakness of women. He argues that the female character’s bravery in confronting the jinn-possessed man leads to her rescue, while dominant religious views criticize such courage in women and regard belief in jinn as superstition. In the film’s universe, formal religion is absent, and religious practices do not function as they do in the real world, thus allowing the film to offer a critical or ironic commentary on the role of religion in confronting supernatural or spiritual concerns.

Ārizū Shādkām, in a brief note published in 2008, provides an overview of topics such as the history of the horror genre in Iran, the interplay between horror and comedy, the role of women in the genre, and the insufficient attention given to the horror genre in Iranian cinema.32Ārizū Shādkām, “Nigāhī bi zhānr-i vahshat va sīnimā-yi jināyī-pulīsī-i Īrān: Kābūs-i Vahshat dar Sīnimā-yi Īrān,” Naqd-i Sīnimā, 54 (2008): 44–45. On the relationship between horror and comedy, Shādkām argues that comedy can complement the horror and help attract an audience. For instance, she regards this element as a strength of the film Girls’ Dormitory. However, she believes that the excessive use of comedy in this film overshadows its horror elements.

Husām al-Dīn Islāmī examines five Iranian horror films, including The 29th Night, The Enclose (Harīm, 2011), Cottage (Kulbah, 2009), The Postman Doesn’t Knock 3 Times (Pustchī sih bār dar nimīzanad, 2009), and Girls’ Dormitory (2004), analyzing elements such as the monsters’ characteristics, and habitat. He also analyzes the narrative elements of the screenplays and the visual elements of the films, such as lighting style, architecture, and set design. However, Islāmī does not analyze the process of each monster’s creation, the specific frightening traits it embodies, or its connection to the political and social transformations of the era. A significant critique of his analysis is that the elements he employs to study horror films lack a defined theoretical framework.33See, Husām al-Dīn Islāmī, “Guzashtah va Āyandah-yi Fīlm-i Tarsnāk dar Sīnimā-yi Īrān,” (Master’s thesis, University of Art, Cinema and Theater, Tehran, 2011).

Figure 6: A still from the film The Postman Doesn’t Knock 3 Times (Pustchī sih bār dar nimīzanad), directed by Hasan Fathī, 2009.

A Definition of the Horror Genre

The entry on horror films in the Schirmer Encyclopedia of Film defines the genre as follows:

Horror films take as their focus that which frightens us: the mysterious and unknown, death and bodily violation, and loss of identity. They aim to elicit responses of fear or revulsion from their audience, whether through suggestion and the creation of mood or by graphic representation. Horror paradoxically provides pleasure, providing a controlled response of fear that is presumably cathartic. Stories of fear and the unknown are timeless, no doubt beginning around the prehistoric campfire.34Barry Keith Grant, ed. Schirmer Encyclopedia of Film, vol. 2 (Thomson Gale, 2007), 391.

Based on this definition, both the audience’s response to what is perceived as frightening and the thematic elements that provoke fear are key aspects of horror films. According to this definition mentioned earlier, the subject matter of such films can be classified into three main categories:

1) Entering the realm of the supernatural and the unknown.

2) Violating the body’s secure boundaries (crossing the line between what is normal and what is terrifying or unnatural by disrupting the body’s natural state).

3) The loss of identity, which can also be interpreted as a violation of the human psyche.

Schirmer Encyclopedia goes on to refer to other fears:

Horror films address both universal fears and cultural ones, exploiting timeless themes of violence, death, sexuality, and our own beastly inner nature, as well as more topical fears such as atomic radiation in the 1950s and environmental contamination in the 1970s and 1980s.35Barry Keith Grant, ed. Schirmer Encyclopedia of Film, vol. 2 (Thomson Gale, 2007), 391.

Therefore, this classification could be expanded to encompass issues such as the fear of both natural and unnatural disasters, whether caused by humans or non-human entities. In defining the horror genre, Cherry highlights not only the various themes that evoke fear in the audience but also the desired response from viewers, emphasizing the significance of viewers’ reactions in classifying a film as part of the horror genre: “The principal responses that a horror film is designed to exploit, is thus a more crucial defining trait of the horror genre than any set of conventions, tropes or styles.”36Brigid Cherry, Horror (New York: Routledge, 2009), 4. She argues that filmmakers of this genre continually redefine its boundaries and adapt their techniques for inducing fear, ensuring that audiences do not become accustomed to a fixed formula. Cherry explains that a key element of the horror genre is how films are designed to provoke specific emotional responses from the audience:

Thus, any film that shocked, scared, frightened, terrified, horrified, sickened, or disgusted, or which made the viewer shiver, get goosebumps, shudder, tremble, jump, gasp or scream in fear could be classified as horror.37Brigid Cherry, Horror (New York: Routledge, 2009), 16.

Cherry also writes about films that were not originally intended to be horror films but still evoke some of the aforementioned reactions from the audience:

Accounts of genre should not just engage with film form, then, but with function and intended audience as well (and in this respect the marketing of films and the construction of audience expectations, together with the receptions of genre films, as well as aspects of the texts themselves, are all important considerations in analyzing the horror genre).38Brigid Cherry, Horror (New York: Routledge, 2009), 16.

Drawing on Rick Altman, a prominent theorist in the field of genre studies, Cherry introduces the concept of “genre hybridity” to analyze certain horror films. She quotes Altman, stating: “Not all genre films relate to their genre in the same way or to the same extent.”39Brigid Cherry, Horror (New York: Routledge, 2009), 27. Regarding the definition of “genre hybridity,” Cherry once again quotes Altman, who defines as “ the cross-pollination that occurs between genres to produce recombinant forms – borrowing conventions from one or more different genre(s) and mixing them up with horror genre conventions.”40Brigid Cherry, Horror (New York: Routledge, 2009), 3.

Cherry provides examples of horror films that have been created through the process of “genre hybridity:”

The Silence of the Lambs employs several visual and narrative patterns of the thriller, but is about the rite of passage of a final girl; Alien (Carol Clover 1992 includes Ripley in her list of final girls) is a combination of the mise-en-scène of a science fiction film with the psycho-sexual themes of horror.41Brigid Cherry, Horror (New York: Routledge, 2009), 27.

Figure 7: A still from the film The Silence of the Lambs, directed by Jonathan Demme, 1991.

Cherry also provides the following classification of the major sub-genres of horror: gothic, supernatural, mystery, and ghost films; psychological horror films; monster films; slasher films; body horror films; splatter films; blood and gore films; exploitation cinema; video nasties; and other films featuring explicit violence.42Brigid Cherry, Horror (New York: Routledge, 2009), 5–6. Based on her classifications, we can briefly outline the key aspects that should be considered when analyzing a film in the horror genre:

1) The factors that contribute to the film’s horror could include the mysterious and unknown world, death and physical violence, loss of identity, atomic radiation, environmental pollution, mysterious diseases, and other components associated with sub-genres of horror. 2) The film’s genre hybridity and its potential to extend beyond the confines of the horror genre. 3) The filmmakers’ intentions in presenting frightening scenes and evoking a specific emotional reaction from the audience. 4) The film’s promotional goals, establishing an unspoken agreement with the audience, and how posters, advertisements, and promotional materials influence the audience’s perception of the film’s genre.

The classification of Iranian horror films

Table 1 classifies Iranian horror films. This classification is based on the definitions and criteria established for the horror genre. It is important to note that whether or not these films succeed or fail in frightening the audience, or whether the final product is critically acclaimed, is not a criterion in this categorization.

|

Film Title |

Year of Production |

Source or Theme of Fear |

What Triggers the Fear |

Genre Hybridity |

Sub-Genre |

|

The 29th Night (Shab-i Bīst-u Nuhum) |

1989 |

Popular beliefs about an unknown woman who casts spells on others (The unknown realm and influence on the human psyche) |

Presence of a woman |

Non |

Supernatural |

|

The Ethereal (Asīrī) |

2002 |

The return of the spirit of a woman who died in the past (The unknown realm and its influence on the human psyche) |

Presence of a woman |

Horror – Mystery |

Supernatural |

|

Girls’ Dormitory (Khābgāh-i Dukhtarān) |

2004 |

A man who appears to be insane threatens the girls in a dormitory with death (Fear of death and physical threat) |

Presence of a man |

Horror |

Psychological – Slasher |

|

Iqlīmā |

2007 |

A woman who appears at a couple’s house at night (Fear of death and the unknown realm) |

Presence of a woman |

Horror |

Mystery – Psychological |

|

Parkway (Pārkvay)

|

2006 |

A psychotic boy who attracts girls and then threatens them with death (Fear of death and physical threat) |

Methods of killings |

Horror |

Slasher Psychological |

|

Leila’s Sleep (Khāb-i Laylā) |

2007 |

The return of the spirit of a little girl who died in the past (Unknown realm and influence on the human psyche) |

Presence of a little girl |

Horror-Mystery |

Psychological-Supernatural |

|

The Postman Doesn’t Knock 3 Times (Pustchī sih bār dar nimīzanad) |

2009 |

A killer’s presence in a house affected by temporal distortion (Fear of the unknown realm and death) |

Nightmares of a house’s inhabitants |

Horror |

Supernatural |

|

Cottage (Kulbah) |

2009 |

A corpse that seemingly comes back to life (Unknown realm) |

Body relocation |

Horror-Crime |

Supernatural |

|

The Enclose (Harīm) |

2011 |

Serial killing of several tourists in an abandoned village—the return of villagers’ spirits (Unknown realm) |

The characters are ghosts |

Horror-Mystery |

Supernatural |

|

Āl |

2010 |

The presence of a mysterious neighbor woman – belief in an unknown entity called “Āl” and its psychological impact on the main character (Unknown realm) |

A neighbor woman and her potential violent actions |

Horror |

Psychological-Supernatural |

|

Fish and Cat (Māhī va Gurbah) |

2013 |

The presence of a wandering killer in a lake and the serial killing of several young people (Fear of death and physical threat) |

The death or disappearance of young people, one by one |

Horror – Mystery |

Slasher |

|

A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night |

2014 |

The presence of a female vampire who attacks men (Fear of death and physical threat) |

Woman’s attacks |

Horror-Romance |

Monstrous – Physical horror |

|

Under the Shadow |

2016 |

The presence of a supernatural figure in the shape of a chador resembling a djinn (Unknown realm) |

Djinn attacks |

Horror |

Supernatural |

|

Zār |

2016 |

Characters possessed by spirits (unknown realm) |

Possession of each character by a djinn – Djinn attacks |

Horror |

Supernatural |

|

The Night (Ān Shab) |

2020 |

A couple trapped in a hotel where, apart from them, the other guests are abnormal (Unknown realm) |

The abnormal nature of a hotel and its inhabitants |

Horror |

Supernatural |

A Review of Notable Horror Films

The 29th Night, by Hamīd Rakhshānī

Wood’s concept of the “Other” highlights how women are often portrayed as outsiders or in a patriarchal society, where their autonomy and independence are systematically denied or suppressed.43Robin Wood, Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan…and Beyond (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 66. Thus, it can be argued that in a patriarchal system, the woman is helpless, confined, and subjugated. The 29th Night can be discussed from this perspective.

At the beginning of the film, a girl named Muhtaram is born. When her umbilical cord is cut, the mother of a boy named Ismāʿīl asks the Muhtaram family to agree that their children will marry when they come of age, meaning Muhtaram is to marry Ismāʿīl in the future. According to Hasan Ẕulfaghārī: “It was customary that when cutting a child’s umbilical cord, a wish would be made, based on the belief that the child would inevitably follow the path wished for them throughout their life.”44Hasan Ẕulfaghārī, and ʻAlī Akbar Shīrī, Bāvar´hā-yi ‛Āmiyānah-yi Mardum-i Irān (Tehran: Nashr-i Chishmah, 2017), 676. This introduction of the film immediately presents the woman as the “Other,” someone who has no control over her destiny from the moment of her birth. Muhtaram is portrayed as the embodiment of a victimized woman, someone who, without agency, must marry Ismāʿīl according to an agreement made for her (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Muhtaram as the embodiment of a victimized woman in The 29th Night (Shab-i bīst u nuhum), directed by Hamīd Rakhshānī, 1989.

At the time of Muhtaram’s marriage to Ismāʿīl, a woman named Zahrā and her sisters were living next door to Muhtaram’s house. One of Zahrā’s sisters, Ātifah, had a husband who divorced her due to her infertility. Now, Zahrā was searching for a husband for Ātifah, hoping to relieve herself from the responsibility of covering her expenses. In a key scene, Zahrā blames Ātifah, saying that she can no longer bear the responsibility of taking care of her. Zahrā is worried that, because of Ātifah’s divorce, people would gossip about their family and that the other sisters would also struggle to get married.

Ātifah, who has repressed any desire or affection for a man in the traditional society shown in the film, is about to enter Ismāʿīl’s life, hoping not to burden her sister and to reclaim her identity through marriage. Ātifah’s repressed desires resurface, and she now threatens Muhtaram in the form of a monster, while at the same, in the form of an alluring woman, drawing Ismāʿīl toward her. Ātifah’s emotions or desires, once repressed, are now expressed outwardly, becoming a powerful force for her. Ātifah reappropriates the popular beliefs and traditions that victimized her to turn them against the society that created them. She knows that if she appears in Muhtaram’s private space after the birth of her child and frightens her, Muhtaram will be seen as “cursed” or “bewitched” by the community.45Hasan Ẕulfaghārī, and ʻAlī Akbar Shīrī, Bāvar´hā-yi ‛Āmiyānah-yi Mardum-i Irān (Tehran: Nashr-i Chishmah, 2017), 749. With her power, Ātifah is able to challenge the beliefs of this family and eliminate Muhtaram. Her powerful presence as a monster on the rooftop, watching over Husayn, clearly demonstrates the transformation of someone who has been suppressed in society into a figure of power and fear (Figure 9).

Figure 9: The appearance of the monster on the roof in The 29th Night (Shab-i bīst u nuhum), directed by Hamīd Rakhshānī, 1989.

Furthermore, the element of family, which Wood identifies as a crucial factor in the birth of the monster, is also linked in the film to traditional and popular beliefs. The family acts as a form of repression, setting the stage for the monster’s emergence. The monster is a product of a patriarchal and traditional society that uses people’s beliefs against them.

The monster uses deeply ingrained beliefs in society and exploits Ismāʿīl’s emasculation as a passive man controlled by his father to influence his life. Constantly repressing his desire for authority and rebellion against his father, Ismāʿīl seems helpless but gradually tries to break free from his father’s dominance and engages in subversive actions in society. Initially, he decides to pursue a different career from his father’s and establish his own independent business. After the monster makes Muhtaram sick and isolates her, Ismāʿīl, tempted by Ātifah, decides to tell his mother that he wants to marry Ātifah through sīqah (temporary marriage) during Muhtaram’s absence (Figure 10). His desire leads him to stand up against his family and, despite the gossip surrounding him, marry Ātifah. Therefore, the monster causes Ismāʿīl’s suppressed desires or emotions to resurface.

Figure 10: Ātifah tempting Ismāʿīl in The 29th Night (Shab-i bīst u nuhum), directed by Hamīd Rakhshānī, 1989.

The film The 29th Night reflects the anxieties of Iranian society in the 1960s, during a time when the nation was shifting towards modernism. Traditional beliefs were slowly giving way to subversive and long-repressed ideas, making it increasingly difficult for the patriarchal system to maintain its dominance. In addition to Ismāʿīl mocking traditional values, Muhtaram’s love for him is completely beyond the understanding of society at the time. In a society where men viewed women as commodities, addressing them with phrases like “women are a curse,” “a woman’s presence is one disaster, her absence another,” or “I didn’t think a divorced woman would have many marriage options,” Muhtaram’s love for Ismāʿīl is progressive and beyond the comprehension of her society. Her true love is only recognized once Muhtaram is no longer alive.

What fate awaits the monster in the end? According to Wood, in horror films, a happy ending often signifies the re-establishment of the repressive system:

One might say that the true subject of the horror genre is the struggle for recognition of all that our civilization represses or oppresses, its re-emergence dramatized, as in our nightmares, as an object of horror, a matter for terror, and the happy ending (when it exists) typically signifying the restoration of repression.46Robin Wood, Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan…and Beyond (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 75.

Wood’s assertion applies to films in which the monster is, in the end, killed and eliminated. However, in the conclusion of The 29th Night the monster does not die; instead, it is left to its fate. The crucial point in the film’s ending is that Husayn, Muhtaram’s father, refrains from killing the monster and instead abandons it in the bazaar. The monster fleeing into this central hub of traditional culture symbolically and metaphorically signifies the monster’s infiltration into Iranian society (Figure 11). One of the men in the bazaar, who has also fallen victim to the monster, puts it bluntly: this monster is “the child of the devil.” When the monster is left on its own, there remains a lingering fear that it may return at any moment.

Figure 11: The monster fleeing into the bazaar in The 29th Night (Shab-i bīst u nuhum), directed by Hamīd Rakhshānī, 1989.

A horror film that reflects the anxieties of its society does not confine its fear to the time it takes to watch the narrative; instead, it stays with the audience long after the film ends. The source of fear in this film is not limited to a conniving neighbor girl; it extends to a traditional and decaying mindset that can gain control of the people in society. If such beliefs remain the standard for judgment, and this passivity and emasculation—whether in men or women—are transmitted from generation to generation, the fear of the monster’s return will endure. A summary of the film’s aspects that match Robin Wood’s theory can be found in Table 2.

|

The Fate of the Monster |

Connection between the Other and the Monster |

Repressed Issue | Other |

|

The monster does not die in the end; it is left to face its own fate. Whenever society falls back into its traditional beliefs, the monster will return. |

Muhtaram appears as the victim of the monster. |

Muhtaram does not express her desires to her family and represses them within herself |

A woman named Muhtaram, who involuntarily marries a man (the denial of women’s freedom in Robin Wood’s theory) |

|

Ātifah’s repressed desires resurface, and as a monster, they revolt against the traditional society by frightening Muhtaram and seducing Ismāʿīl, drawing a married man toward her. |

Ātifah remains silent in the face of her sister’s reproaches and initially represses her desire to marry Ismāʿīl. |

A divorced woman named Ātifah, who is forced to marry (the denial of women’s freedom in Robin Wood’s theory). |

Under the Shadow, by Bābak Anvarī

In The 29th Night, it is the family that acts as a tool of the patriarchal system, in Under the Shadow, it is the political atmosphere that, through a patriarchal mechanism, strips a woman named Shīdah of her freedom. No longer allowed to work after the revolution, she is introduced as the “Other” from the very beginning of the film and, based on Marcuse’s theory, is subjected to “surplus repression.” Shīdah, who supported left-wing political movements before the Islamic Revolution of 1979, is now seen as representing an “alternative ideology,” which implies that her beliefs are now marginalized and not aligned with the dominant ideology of the Islamic Republic (Figure 12).

Figure 12: Shīdah is seen as a representative of the “alternative ideology” in the new regime in Under the Shadow (Zīr-i Sāyah), directed by Bābak Anvarī, 2016.

She should, ideally, express her anger against the religious and patriarchal dominant system and fight it, but instead she submits to this political regime and represses her anger. As the film progresses, the reason for her repressed anger is revealed. Shīdah’s husband, a doctor, has no choice but to go to war to continue his profession. The emasculation of men in this film is evident as they show no will to resist the dictates of the ruling system. The man must go to war and leave his family behind because if he disobeys this order, he will, like Shīdah, be confined at home. Therefore, when Shīdah’s husband submits to this system, Shīdah herself, due to her responsibilities such as taking care of the child, finds her position weakened in society and is no longer able to resist it.

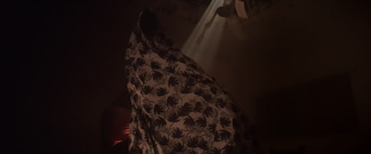

The monster in Under the Shadow differs in one important way from what Wood describes in his theory. Shīdah, introduced as the “Other,” remains a victimized woman but does not become a monster. Instead, the monster in the film, though it has a feminine appearance, represents the same system that suppresses Shīdah. An invisible monster, hidden in a chador, represents all the beliefs that have now infiltrated Shīdah’s home, taking over the once-safe domestic space (Figure 13).

Figure 13: The depiction of the monster wearing a chador in Under the Shadow (Zīr-i Sāyah), directed by Bābak Anvarī, 2016.

An example of this is a key scene in the film where Shīdah, afraid of the monster, steps out of the house without a hijab and is arrested by the police. Her fear reflects the anxiety of people such as Shīdah, who face rapid political and cultural changes and feel they have no longer have a place in Iranian society (Figure 14).

Figure 14: Shīdah fleeing from the monster in her house, only to be arrested by the police for not wearing her hijab. A still from Under the Shadow (Zīr-i Sāyah), directed by Bābak Anvarī, 2016.

In a manner akin to The Exorcist (William Friedkin, 1973), where the monster exploits the rift between the father and mother to infiltrate the household, the monster in this film takes advantage of the absence of the male figure, as well as Shīdah’s and her daughter’s vulnerability, to breach the sanctity of their private space. Based on Wood’s theory, the house—a recurring motif in horror cinema—is presented here as a threatened sanctuary, with the monster’s intrusion undermining its sense of safety.47Robin Wood, Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan…and Beyond (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 80.

Under the Shadow draws on another historical moment, the Iran-Iraq War, as a backdrop for the emergence of its monster. Director Bābak Anvarī depicts this period in Iran as one of rapid political and cultural transition, creating anxiety for Shīdah. The film uses the frightening atmosphere of war and the refuge of dark basements, serving as bombing shelters, to enhance its overall sense of horror. As Anvarī himself mentions in the opening of the film, life in such conditions is filled with darkness, creating fear and anxiety (Figure 15).

Figure 15: Facing the war situation and staying in a war-torn house make the conditions even more terrifying for Shīdah. A still from Under the Shadow (Zīr-i Sāyah), directed by Bābak Anvarī, 2016.

The monster in Under the Shadow not only frightens Shīdah but also focuses on her daughter. Wood describes children in horror films as either as the monster itself or as a medium through which the monster operates.48Robin Wood, Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan…and Beyond (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 67. In this film, the monster transforms Shīdah’s daughter into a vessel for its power, inciting her to rebel against her mother. The daughter’s cooperation with the monster and her role in carrying out its will suggest that the monster seeks to align the child’s thoughts with the ruling system, as opposed to her mother’s beliefs. The climax of this rebellion occurs in a scene where the return of repressed emotions is symbolized by the daughter slapping her mother.

As with The 29th Night, the monster in Under the Shadow does not vanish in the end. Instead, it manages to drive Shīdah and her daughter out of the house. The final shots of the film, showing every corner of the house empty, suggest that the monster remains powerful and that the family will no longer have a safe space there. At the film’s conclusion, Shīdah, dressed according to the imposed regulations of the ruling system, gets into a car to escape with her daughter, signifying her surrender to the political system. Thus, the fear in this film extends beyond its own cinematic world. This monster, symbolizing a force that opposes or suppresses differing beliefs through harsh and excessive control, can represent a situation or system that exists at any time or place. A summary of how the film fits with Wood’s theoretical framework is provided in Table 3.

| The Fate of the Monster | Connection between the Other and the Monster | Repressed Issue |

Other |

| The monster does not perish in the end and drives Shīdah and her daughter out of the house. The monster can still attack any woman with Shīdah’s mindset |

Shīdah appears as a victimized woman. However, the monster, wearing a feminine chador that represents the ruling system, attacks Shīdah in her home. |

Reacting to and protesting the surplus repression of society.

|

A woman named Shīdah who is not allowed to practice medicine (denial of women’s freedom in Robin Wood’s theory) |

|

Shīdah’s daughter becomes a means for the monster to frighten her mother.

|

Reacting to the mother’s beliefs.

|

Shīdah’s daughter, who is distrustful of her mother, while her mother suppresses her own fear (child repression in Robin Wood’s theory). |

|

|

Shīdah, as the representative of an ideology, becomes the victim of the monster. |

The reaction of those who follow this ideology to the dominant one. |

Shīdah’s leftist ideology before the revolution (alternative ideology in Robin Wood’s theory). |

A look at other Iranian horror films based on Robin Wood’s Theory

In this section, we will explore several other Iranian horror films whose monsters fail to accurately reflect anxieties relevant to social transformations. Although these films may scare the audience in some scenes, they fail to leave a lasting impression. Subsequently, it will be argued that by following Robin Wood’s model and grounding the creation of the monster in a strong socio-political foundation, these horror films could have evoked a more enduring fear in the audience while still achieving their primary goal of frightening and entertaining.

In Girls’ Dormitory (2004), directed by Muhammad Husayn Latīfī, the monster is a man who, having failed to win the affection of his lover, now seeks revenge by attempting to kill the girls in a dormitory. His behavior suggests that he has lost his mental stability. However, the film does not provide enough attention or detail to the antagonist to help the audience understand his role, social status, or background. This character has great potential, as a working-class member of society, to fit into Wood’s model of the “Other” (Figure 16). Had this aspect of his character been explored in the film, we could have seen a monster who, due to his lower social class and unattractive appearance, was scorned by his lover’s family.

Figure16: The depiction of the monster in Girls’ Dormitory (Khābgāh-i Dukhtarān), directed by Muhammad Husayn Latīfī, 2004.

Then, his repressed desires towards women would have resurfaced, transforming him into a monster emerging from society’s rejection. In that case, the terrifying nature of the film would have been enriched, and the film, as a horror genre piece, would have adopted a more responsible and serious approach towards its depiction of this social class. A comparable example could be The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (Tobe Hooper, 1974), where the monster is portrayed as coming from the working class. The killing of three workers in a burning oil storage unit, as narrated at the beginning of the film, is later reflected in the depiction of Leatherface and his family as outcast members of society, prone to rebellion. Moreover, their life in a small town, their background as former slaughterhouse workers, and their wearing of workers’ uniforms further reinforce this working-class portrayal.

In the film The Postman Doesn’t Knock 3 Times (2008), directed by Hasan Fathī, a man named Ibrāhīm arrives at a three-story, isolated house and kidnaps another man’s daughter hostage to settle a personal score with him. The filmmaker designates each floor of the house to represent a distinct historical period in Iran. The ground floor represents the contemporary narrative of Ibrāhīm and his personal feud, the second floor depicts a marital relationship from the late 1960s, and the third floor tells the story of a Qājār prince during the early years of Rizā Shah Pahlavī’s rise to power. The shared element across these three floors is a young boy who comes and goes between them. By the end of the film, it is revealed that this boy is the father of the girl whom Ibrāhīm, in the contemporary narrative, has taken hostage (Figure 17).

Figure 17: The depiction of the young boy who is destined to be a monster in the future in The Postman Doesn’t Knock 3 Times (Pustchī sih bār dar nimīzanad), directed by Hasan Fathī, 2009.

At first glance, this storyline has the potential to create a monster-child (one of Wood’s “Others”) within a historical context, examining how this boy, amidst the political and social changes in Iran, becomes a contemporary monster. However, in conclusion, the filmmaker undermines this possibility by attributing the birth of the monster-child solely to the absence of a mother. At the end of the film, Ibrāhīm and the girl decide to go to the third floor and kill the boy, preventing him from moving between historical periods. However, when they realize that the boy’s mother is still alive, they leave him, believing that with her presence, the boy will be able to lead a different life. The filmmaker addresses various historical periods in each narrative, all sharing the common theme of the oppression of women. Yet, instead of tracing the monster’s origins within this historical repression, the filmmaker offers an irrelevant explanation for its birth.

In The Enclose (2009), directed by Rizā Khatībī, we are presented with a series of murders involving English tourists in a mysterious village where all the inhabitants are dead. Thus, it appears that the film targets the fear of a foreign culture or an alternative ideology as the primary source of horror. However, once the murders are resolved, the detective protagonist uncovers the fate of his missing child in the village. Aside from the question of why the spirits of the village inhabitants would assist a detective in locating his child, the simplistic resolution of the serial murders and the unresolved identity of the monster squander the film’s potential to be truly terrifying (Figure 18).

Figure 18: The depiction of the spirits of the village, assumed to be the monster in The Enclose (Harīm), directed by Rizā Khatībī, 2011.

In Fish and Cat (2013), directed by Shahrām Mukrī, a middle-aged restaurant owner, in collaboration with his friend, murders a series of young campers near a lake. This film, inspired by Friday the 13th (Sean Cunningham, 1980), tends towards the slasher subgenre, while also retaining an element of mystery. However, the film’s atmosphere and the nature of its killer draw little from the generic conventions. Of course, this may be because the restrictions on depicting explicit violence in Iranian cinema have limited the film’s ability to fully adhere to the slasher subgenre. That said, the more pressing question about this film is what type of ideology or social class the killer belongs to. Is the conflict between the traditional mindset of previous generations and today’s youth a recurring theme in this film? Does the killer embody an ideology that corresponds to the socio-political issues of the time? If the filmmaker had integrated a subtle socio-political background for the killer, the film could have offered a deeper and more compelling horror experience—one that emerges from real-world anxieties of the time.

In A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014), directed by Ana Lily Amirpour, a fully veiled woman appears as a vampire, sacrificing men to suck their blood. The act of men being victimized by an Iranian female vampire dressed in religious attire obviously evokes a political metaphor for the woman’s motivations, considering the historical context of women’s oppression in Iran (Figure 19).

Figure 19: The depiction of the vampire woman in a chador as the monster in A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, directed by Ana Lily Amirpour, 2014.

However, the absence of a robust socio-political context and a clearly defined motivation for her actions reduce the film to a rather superficial work, ultimately preventing it from achieving its potential impact. Unanswered questions, such as the woman’s family background, when and how she became a vampire, and why she targets certain men, undermine the film’s engagement with political and social issues beyond its own limited world. Throughout the film, the female vampire kills men who wish to engage with her; the film’s climax shows the woman falling in love with one of these men and choosing not to kill him. By reducing the fundamental fear and horror to a simple romance, the film limits its own potential for cultural impact.

Conclusion

With an effective and committed approach, a horror film can reflect the anxieties and political and social transformations of its time. The most important element in achieving this is creating a monster or source of fear rooted in social anxieties. Wood’s approach provides valuable insight by connecting the concept of the “Other”—a marginalized and oppressed group—to the monster in a wide range of horror films. The deeper this connection, the more effectively the film can serve as a powerful reflection of social anxieties and oppression. For example, films such as The Postman Doesn’t Knock 3 Times or Girls’ Dormitory fail in this respect because they do not establish a clear connection between the social “Other” and the monster of their films. In contrast, the success of a film like The 29th Night lies in its accurate portrayal of traditional Iranian society on the brink of modernity. This understanding is reflected as a woman, oppressed by traditional beliefs, transforms into the monster of the film, fitting perfectly into the category of the “Other” as described in Wood’s theory. Similarly, Under the Shadow successfully gives significance to its monster by combining a supernatural woman, representing an external repressive ideology, with a child who serves as the monster’s mediator. This combination forms a complete portrayal of a woman’s fear during the war.

The horror born from societal anxiety should not end with the closing credits of a film. The fear lingers with the audience long after the movie ends, and the viewer knows it could, like an undefeatable monster, return at any time. This type of horror is more impactful than entertainment-driven horror, which confines the film to a one-time experience in the movie theater. In this way, the film’s “safe space” functions not only as a medium for the audience to psychologically release their own fears but also as a mechanism for society to face and address collective fears in a meaningful way. In summary, this type of horror encourages the audience to continue reflecting on their own reactions, offering a deeper, more complex understanding of the source and nature of the fear, and perhaps what they can do to assuage it.

Cite this article

This article offers a critical examination of the horror genre in post-revolutionary Iranian cinema through the theoretical lens of Robin Wood’s concept of horror as the return of the culturally repressed. Despite its marginal presence within Iranian cinematic history, horror has increasingly emerged as a potent genre for articulating collective anxieties and negotiating sociopolitical tensions in the aftermath of the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Drawing on Wood’s framework, this study interrogates how Iranian filmmakers mobilize horror aesthetics to navigate themes that remain culturally or politically sensitive, including gendered subjectivity, state violence, moral panic, and the policing of desire. Through close textual analysis of selected films, the article demonstrates how the horror genre, often reconfigured within local narrative and aesthetic constraints, operates as a coded critique of hegemonic power structures and ideological repression. In doing so, it positions Iranian horror not as a deviation from global genre norms, but as a contextually embedded mode of resistance and expression, reflecting the unique intersection of censorship, trauma, and creativity in contemporary Iranian filmmaking.