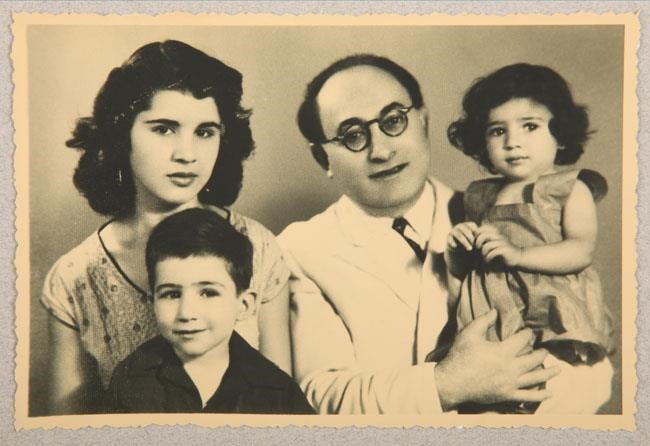

Uvānis Uhāniyān: Director of the First Feature Film in Iran

Figure 1: A portrait of Uvānis Uhānīyān.

Uvānis Uhāniyān (Ovanes Ohanian), also known as Uvānis Ugāniyāns (1896-1960), the director of the first feature film in Iranian cinema, led a mysterious life. Historians have often been puzzled by the inconsistent statements of Uhāniyān and those close to him about his place of birth, name, education, occupation, cinematic activities and political inclinations, leading to the creation of different and paradoxical narratives about his works and his past. Consequently, some historians have called Uhāniyān a storyteller and some, a charlatan. Since the day he came to Tehran, he had been telling stories about his past, none of which could have been verified.

In the 1950s, the magazine ‘Ittilā‛āt-i Haftigī (The Weekly News) wrote in a biographical sketch of Uvānis Uhāniyān that he was born in Mashhad,1“Lose No Time, Bald Men!” ‘Ittilā‛āt-i Haftigī 890 (October 10, 1958): 10. although Uhāniyān himself had mentioned in an interview with the same weekly that his birthplace was the Caucasus.2“An Iranian man has invented 24 types of jet and rocket bomber airplanes and three types of flying saucers and has named one of them Iranian Parastoo.” ‘Ittilā‛āt-i Haftigī 831 (August 16, 1957):12, 32-33. Thirty years later, a note by Uhāniyān was discovered which revealed that he believed he was born in the Caucasus in a village called Tugh in the Nagorno-Karabakh region.3 ‛Abbās Bahārlū (Ghulām Haydarī), “Documents from Iranian Cinema,” National Cinematheque Newsletter, nos. 10 and 11, 193. Khānbābā Mu‛tazidī Khānbābā Mu‛tazidī, one of the first cinematographers of the Iranian cinema and Uhāniyān’s collaborator in his first film, once said that Uhāniyān was born in Ashgabat in Turkmenistan based on what he had heard from Uhāniyān’s daughter, Zimā.4Jamāl Umīd, Uvānis Ugāniyāns: Zindigī va Sīnimā. (Tehran: Tehran Fāryāb Publications, 1984), 13. Most historians of Iranian cinema, including Hamid Naficy, believe that Uhāniyān’s birthplace is Ashgabat5Hamid Naficy, Social History of Iranian Cinema: Workshop Period, 1897 to 1940, trans. by Muhammad Shahbā (Tehran: Mīnū-yi Khirad, 2015), 264 However, since Uhāniyān was ethnically Armenian, some have also considered his family immigrants from Armenia.6‛Abbās Bahārlū (Ghulām Haydarī), “Dar fāsilah-i du kūditā (az 1299 tā 1332 sh.),” Tārīkh-i tahlīlī-i sad sāl sīnimā-yi Īrān. ed. ‛Abbās Bahārlū (Tehran: Cultural Research Institute, 2000), 35.

Uhāniyān has given two different accounts of his childhood: in one narrative, he said that after he was born, his parents immigrated from Iran to Uzbekistan and he was educated in the Trade School of Tashkent. Then, he took an interest in the arts and went to Moscow to study at a filmmaking school.7‘Ittilā‛āt-i Haftigī, no. 890, 10. In another narrative, he said that he immigrated with his mother from the Caucasus to Turkmenistan to live with his father who had a cotton factory in Ashgabat. He mentioned that he studied law and cinematic affairs in Ashgabat and was a judge at the judiciary for a period of time.8‘Ittilā‛āt-i Haftigī, no. 832, 12 He had also claimed that he was chosen as Iran’s consul in Siberia in 1921 by the Imperial Government of Iran, but he got tired of living in Russia after a while and returned home.9‘Ittilā‛āt-i Haftigī, no. 832, 32.

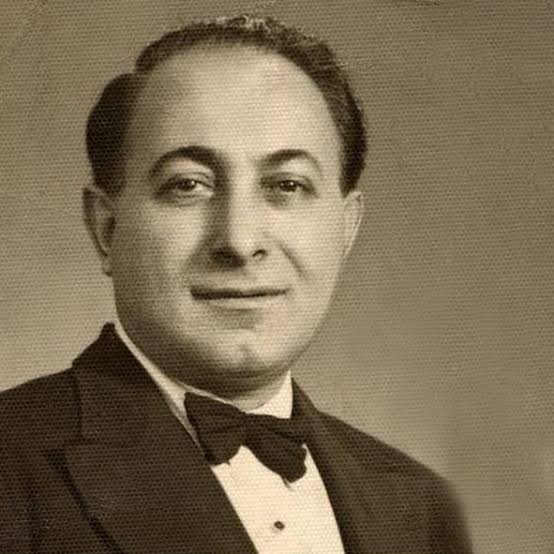

Figure 2: A portrait of Uvānis Uhānīyān in his youth.

The important point is his education at the Moscow Film School, where he got familiar with the principles of directing, acting, and scriptwriting.10Emily Jane O’Dell, “Iranian-Russian Cinematic Encounters,” In Iranian-Russian Encounter: Empires and Revolution since 1800, ed. Stephanie Cronin (Routledge, 2013), 330. According to Uhāniyān himself, after graduating from this school, he participated in the first Moscow Film Congress in 1928, where Sergei Eisenstein, Vsevolod Pudovkin, and Aleksandr Aleksandrov were also present. Based on this narrative, Uhāniyān was a member of the central committee of the Supporters of Soviet Cinema from 1926 to 1928 before his acceptance in the Soviet Cinema Experts Group in 1928. In the same year, he became a member of the general board of photo and film exhibition in Russia. Shortly after, he was one of the five people responsible for reviewing and censoring films. In the same year, he went back to Turkmenistan to become the founder and the president of the country’s Board of Cinema. He established the first screenwriters’ circle in Turkmenistan and even tried to establish an acting school in its capital.11National Cinematheque Newsletter, 193. These claims were never verified and the name Uhāniyān does not appear in the documents related to the establishment of cinema in Turkmenistan.

Several reasons are mentioned for Uhāniyān’s return to Iran. He himself said that he came back to his country at the request of the ambassador of Iran in the Soviet Union with a recommendation letter from him for establishing cinema in Iran.12‘Ittilā‛āt-i Haftigī, no. 831, 32. His friends, however, quote him tell another story. For example, Ahmad Gurjī, one of Uhāniyān’s students, related that before coming back to Iran, Uhāniyān had been involved with a group in Baku in the making of a film called Rāh-i ‛Alī bih Anzalī (Ali’s Way to Anzali) or Chigūnah Alī bih Khānah Murāji‛at Kard (How did Ali return home)13There is no information available about this film. There is only an advertisement published in Iran Newspaper: “This film has been made with Iranian artists and features Iranian music.” The film was apparently going to be screened in the cinemas of Iran. Iran Newspaper, January 25, 1928, 14. Uhāniyān had observed that in one scene of the film, canons were pointed toward the borders of Iran, as if the enemies of the people of Baku were the Iranians. When he had objected to the producers, he was not taken seriously, which offended him and led him to decide to return to Iran and stay.14Quoted from the radio program Fānūs-i Khiyāl (Lantern of Fantasy), produced and performed by Shāhrukh Gulistān for the BBC Persian Radio. The broadcast of this program series began on September 24, 1993 and was aired in sixteen episodes.

It seems that after his return, Uhāniyān first went to Mashhad and then, in 1929, to Tehran. There are narratives, however, testifying that he immigrated to Iran in 1925 and lived in Mashhad for about four years.15Muhammad Tahāmīnizhād, “Rishah-yābī-i ya’s dar sīnimā-yi Īrān,” Vīzhah-yi sīnimā va ti’ātr 2-3 (1972): 114. In 1925, Mūsā Khan I’tibār al-Saltanah, the chief of Mashhad’s armory, built a movie theater in that city and appointed a young Armenian called Monsieur Ughānuff as its projectionist. The identification information of Ughānuff completely matches with that of Uhāniyān.16Husayn Pūr-Husayn, Sad sāl sīnimā dar Mashhad (Mashhad: Tūs-Gustar Publications, 2010), 20; and Markaz-i Asnād-i Āstān-i Quds-i Razavī, document no. 100844.2. However, Uhāniyān never mentioned this anywhere.

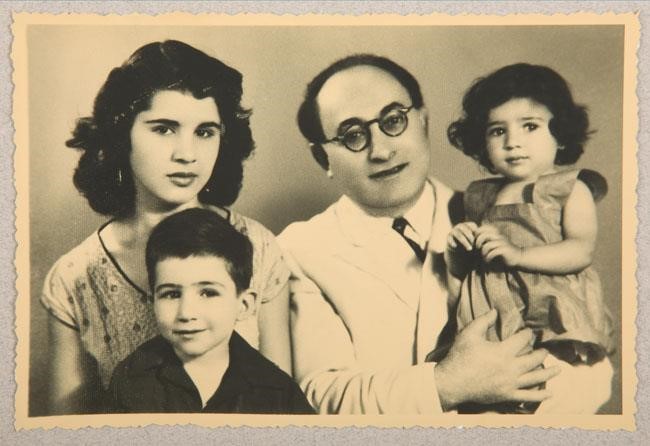

For Uhāniyān himself, as for most of the historians of Iranian cinema, Uhāniyān’s artistic life begins in 1929 when he goes to Tehran with his daughter, Zimā, who was born in Ashgabat, and whose mother Lydia, had not come to Iran. Uhāniyān was employed in 1929 at the police school, where he worked as a teacher. Apparently, his documents showing his legal education and at the trade school gained him his employment. In this period, he was trying to get closer to the Iranian society and think of Iran as his homeland, against the beliefs of most Armenians who believed that they were living in diaspora. Therefore, Uhāniyān’s emphasis on “being Iranian,”, as he later asserted in his interviews, was not in agreement with the views of the Armenian community. Moreover, at that period, the majority of Armenians in Iran were against the Soviet Union and most of them were members of Iran’s Dāshnāk, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (IRF), which fought against the Bolsheviks in various ways.17One of the important Armenian political parties that was founded in 1890 in Tbilisi. They held the government in the short period during Armenia’s independence in 1918, but left the country with the invasion of the Bolshevik forces and most of them came to Iran. Dāshnāk was and is the most important Armenian party in Iran. The suspicion toward immigrants was, more than anything else, due to the spies that came to Iran from the Soviet Union and infiltrated the political groups that were against the Soviet communist regime. It may well be the reason why Uhāniyān told yet another story to the Armenians of Iran about his return: that he escaped the Soviet Union on a carriage and got himself to Afghanistan and then, after three or four sleepless nights, came to Iran.18Karīm Nīkūnazar, Ādam-i mā dar Bālīvūd: zindigī-i pur-mājārā-yi rizhīstur-i mashhūr Uvānis Uhāniyān Ugāniyāns Rizā Muzhdah (Tehran: Chishmah Publications, 1400), 18.

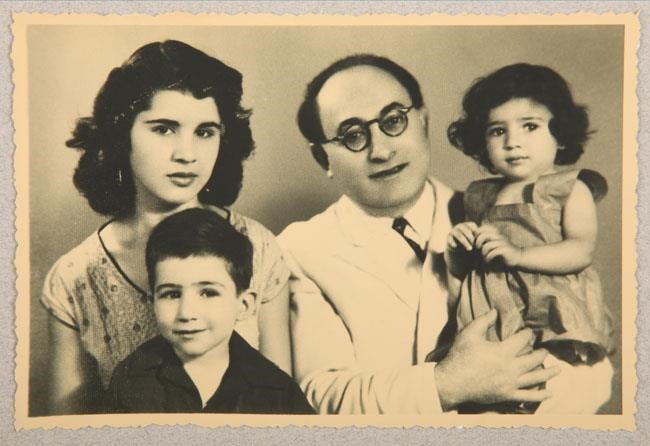

Figure 3: A picture of Uvānis Uhānīyān with his family.

In 1930, Uhāniyān was contemplating making a film, at a time when Reza Shah Pahlavi had explicitly prohibited photography and filming in the streets of Tehran due to the murder of Robert Imbrie, the Vice Consul of the United States in Tehran.19Robert Imbrie occasionally photographed for the National Geographic magazine. In those days, rumors had it that a blind person had found his eyesight after supplicating to a saqqākhānah (a drinking fountain in a holy shrine) in Tehran. Imbrie went there to take photos, but people, believing that he was of the Baha’i faith, attacked him and his guard and killed him. Also influential in this decision was the making of two documentary films, Grass: A Nation’s Battle for Life (1925) and Yellow Expedition (1934),20Grass: A Nation’s Battle for Life, was made in 1925 about the journey of the Bakhtiari nomadic tribe with the collaboration of Merian C. Cooper, Ernest B. Schoedsack, and Marguerite Harrison. The Pahlavi government banned the screening of the film because of its depiction of the poor state of the nomadic tribes and their possession of guns. The Yellow Expedition (1931-1934), directed by Léon Poirier was a documentary produced by the support of Citroën, the French automobile company. This film was banned in Iran because of its depiction of the poor people in the villages in the west of the country, the journey of the nomadic tribes, women in black chador, etc. since Reza Shah believed that Western filmmakers only intended to show the weaknesses of the country. That was the situation in which Uhāniyān intended to make a film, while he did not even have a specific story or a cast or crew to work with. First, he had to find collaborators for producing the film. Uhāniyān believed that theater actors were generally addicted to talking while in cinema, facial expressions play the main role because films were silent at the time21Fānūs-i Khiyāl, part one. He therefore decided to start an acting school and train students in the art of screen acting. Uhāniyān needed money for founding his acting school, and the person who invested in the school was Grisha Sākvālīdzah, better known as Grisha Sākāl, the Georgian owner of Sīnimā Māyāk in Tehran who had come to Iran after the Bolshevik revolution.22One of the first movie theaters in Tehran, founded in 1927 on Ittihādīyah Alley, off Lālahzār Street.

On 12 April 1930, the ‘Ittilā‛āt newspaper published the first advertisement for the acting school. The second advertisement was published the next day.23Iran Newspaper, April 13, 1930, 4. That the advertisement of the acting school invited women and girls for learning acting was an significant as in those days, acting was forbidden for Muslim women and most of the theater actors were Armenians or Zoroastrians. Unconcerned about the existing limitations in Iran, Uhāniyān invited women to register at his school, although no women signed up in the first semester.

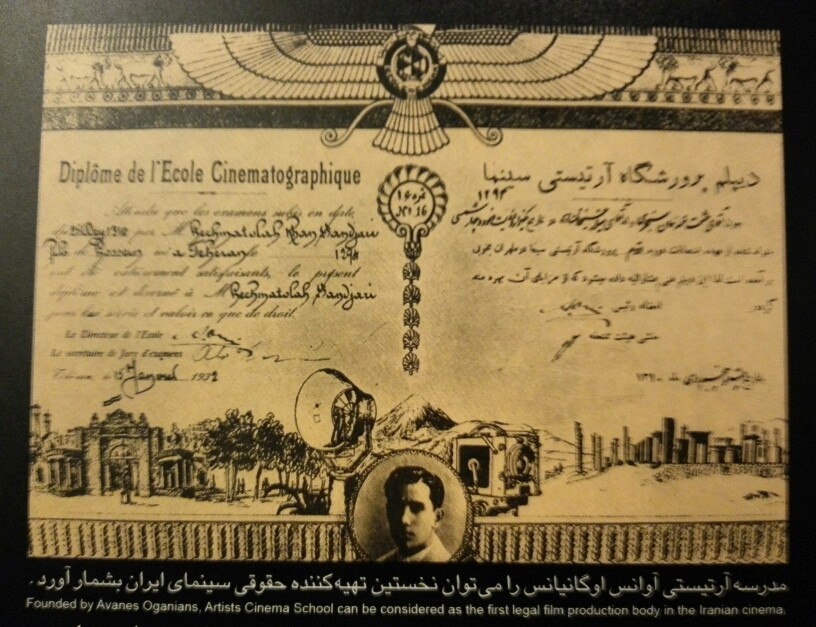

“Madrasah-i Artīstī-’i Sīnimā” (The Screen Acting School) was Iran’s first acting school. A few schools were already established for stage acting in Iran, but no one had thought of founding a school for cinematic arts. Therefore, Uhāniyān is also credited as the founder of cinematic schools in Iran.

The first semester of the Acting School began on 10 May 1930. Three-hundred people had registered at the school and were supposed to learn the crafts of acting, photography, calisthenics, boxing, fencing, ballet, Eastern and European dance, screen acting techniques, and acrobatics. But the school’s license was revoked only a few days after classes started due to the inclusion of the word “school” in the title of this art institute. According to the Iranian law, “schools” were required to obtain their licenses from the Ministry of Education, had to follow a specific curriculum and had to use experienced teachers. The Acting School met none of those standards. Uhāniyān wrote a letter to the Ministry of Education and emphasized that he had been assigned by the Iranian government to receive cinematic education and that the police had granted him his work license.24‛Abbās Bahārlū, Tārīkh-i tahlīlī-i sad sāl sīnimā-yi Īrān, 36. He signed this letter as Uvānis Ugāniyāns.as he seems to have been better-known as “Ugānīāns Ugānīāns” in the art society. Later, Uhāniyān chose other names for himself and was seldom called with his original name in Iran.

Figure 4: Diploma of Ohanian’s Artistic Cinema School.

On the other hand, Uhāniyān wrote in this letter that he had been assigned by the Iranian government to study cinema in Moscow; a claim for which he did not produce any evidence. The problem of the Acting School was solved after a month by changing the word “school” to “educational center” and Uhāniyān went on with his job.

Twelve people graduated from the first semester of the Acting School. Uhāniyān decided to make his first film with the help of those graduates. Before starting to shoot films, he founded named “Pers Film,” the first filmmaking company in Iran. “Pers” in the title was a form of “Persia,” the name given to Iran by other countries at the time.

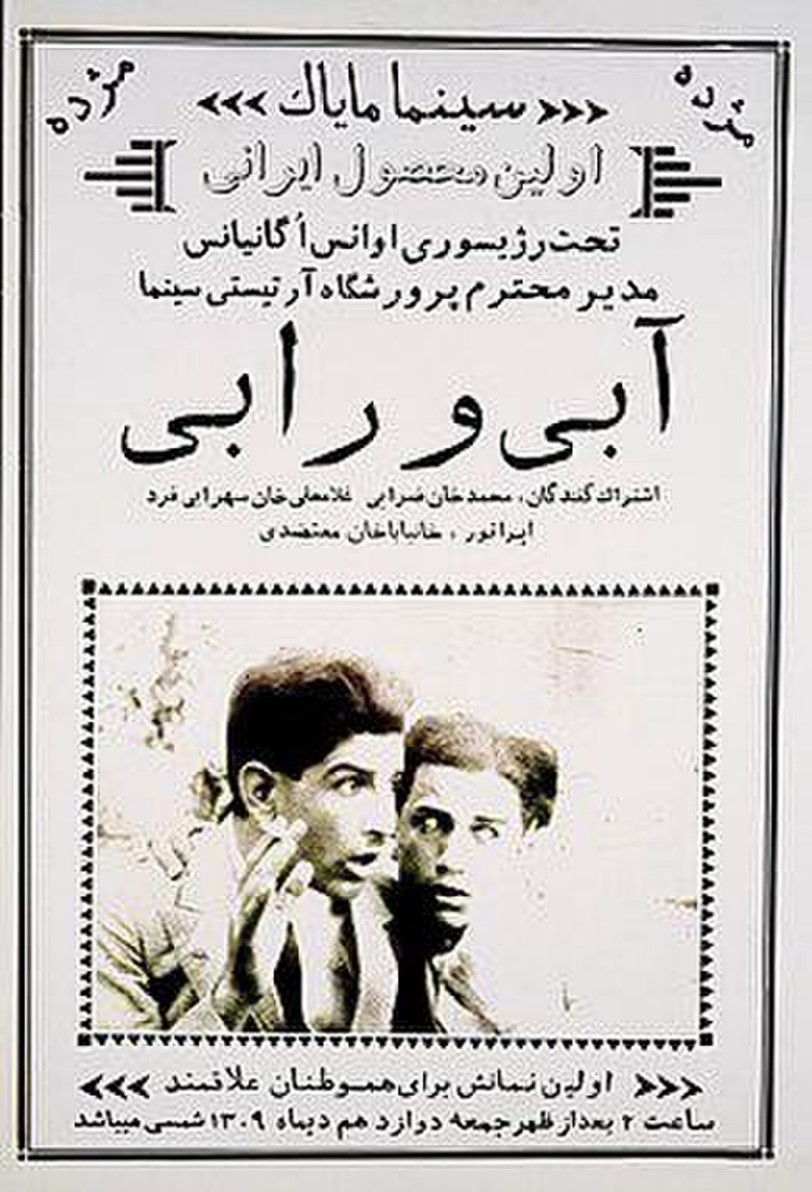

Inspired by the films of two Danish comedians Harald Madsen and Carl Schenstrøm, who were well-known as Pat and Patachon, Uhāniyān wrote a scrip titled Ābī u Rābī (Ābī and Rābī) for a film in several acts, each with a comic or adventurous and action story.25Arbi Avanessian, theater and cinema director, said in an interview in 2002 (in Handes, the Armenian literary and artistic quarterly, no. 5) that Abi o Rabi was influenced by the Armenian director Hamo Beknazarian’s Shor and Shorshor in the first place, which was itself influenced by Pat and Patachon. Shor and Shorshor was made in 1926 and Avanessian believed that it taught Uhāniyān how to bring a story from the western world to the east and get inspired by it instead of copying it. These stories were theses written by the students of the Acting School. Uhāniyān had put them together and added just two new pieces. The title Ābī and Rābī was taken from the names of two students who were acting in the film: Muhammad Zarrābī and Ghulām-‛Alī Suhrābī. The last three letters of the name Zarrābī and the last four letters of the name Suhrābī made up the title Ābī and Rābī. Uhāniyān wrote comic stories for these two characters; for example, one of them was drinking water but the other one’s stomach was getting swollen, or one of them was run over by a heavy roller and got flattened and the other one entered the room and hit him on the head with a hammer and he got short but wide. The other acts featured other graduates of the school. The first act was about three homeless beggars who were dying of hunger and cold weather. The second act was a prison escape story, and the third act showed three thieves in action. The next two acts made a short comedy about the trial of an uneducated dentist, and the last act was composed of acrobatics and variety shows; For instance, the main actor would lift a 104-kilogram bar with one hand and hammered a nail with the other hand, he would tear up a copper tray with bare hands, he would break large cones of sugar with the strike of a finger, etc.

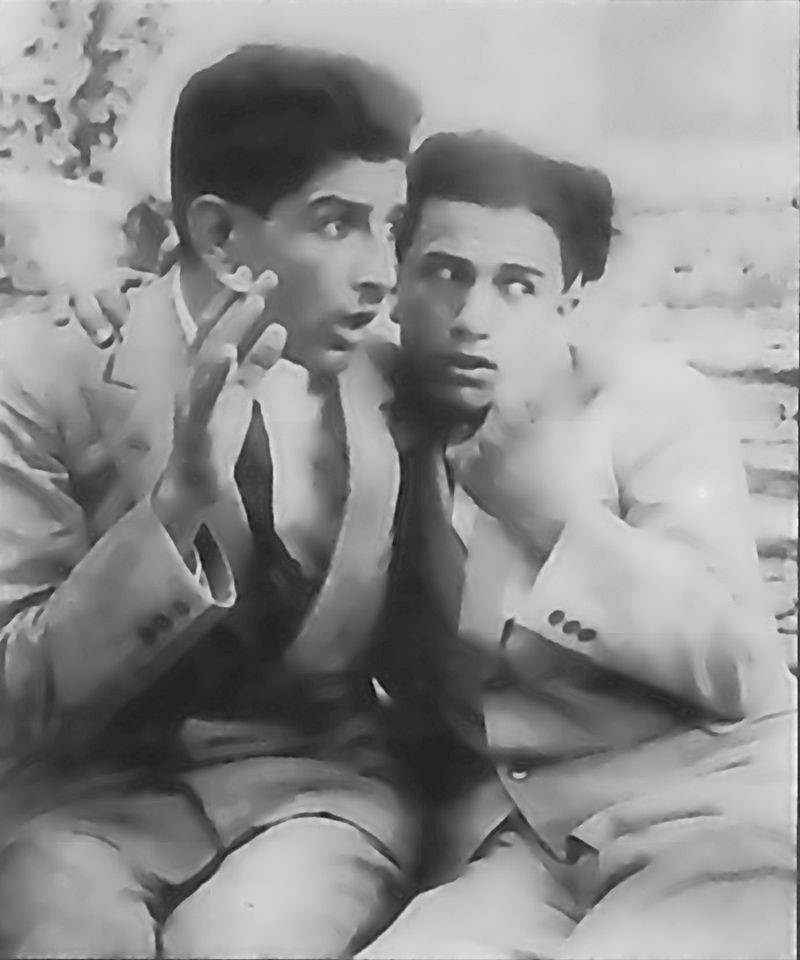

Figure 5: Muhammad Zarrābī and Ghulām-‛Alī Suhrābī in the film Ābī and Rābī, directed by Uvānis Uhānīyān, 1930.

The cinematographer of Ābī and Rābī was Khānbābā Mu‛tazidī who had worked previously at the Gaumont Studio in France. Mu‛tazidī and Uhāniyān owned twenty-five percent of the shares of the film, and Sākvālīdzah owned the other seventy-five percent. Shooting began in November 1930, although most of the negatives that reached Iran were decayed. In such circumstances, Uhāniyān showed his creativity by using positives instead of negatives, although parts of the film were of low quality because of different lighting. The film was ready for screening in December 1930.

Ābī and Rābī, the first feature film in Iranian cinema, was premiered on 2 January 1931 in Sīnimā Māyāk for journalists and government officials. The film was received warmly by journalists as most of them welcomed a feature film made in Iran by an Iranian cast and crew.26For example, Rizā Kamāl, the famous playwright, wrote using his penname, Shahrzād, in Iran Newspaper 4, January 1931: “It was good because it was Iranian. It was good because it led a group of our young fellow countrymen to an industrial and honorable and promising path, and because it can be a model for the other young people who think of no other way than office work for making their livings and do not bother to plow the ground for the fear of the exhaustion of sowing.” The only copy of Ābī and Rābī remained in the possession of Sākvālīdzah, the main investor of the film. This copy was burned in a fire accident in Sīnimā Māyāk in 1932. Today, there is nothing left of this film except for a few photos and the report of the stories of some of its acts.

Figure 6: Poster for the film Ābī and Rābī, directed by Uvānis Uhānīyān, 1930.

Nonetheless, after the success of Ābī and Rābī, Uhāniyān suddenly changed tracks. He founded an institute called Fidirāsiyun-i Bayn al-milalī-i Majāmi‛-i Tahqīqāt-i ‘Ilmī (The International Federation of Scientific Research Societies) in Tehran and announced that his aim was serving humankind by conducting research on science and art.27Umīd, Uvānis Ugāniyāns, 155. To become a member of the federation, one had to be a university graduate or have done valuable services and research in scientific fields. Uhāniyān selected famous literary and political figures as the vice deans of the Federation, and corresponded as its president with famous people such as Cecil B. DeMille, Rabindranath Tagore, and Adolph Zukor. He also granted honorary doctorates to each of them on behalf of the federation28Umīd, Uvānis Ugāniyāns, 173. In the letters that he sent to these people, he introduced himself as Professor Uvānis Uhāniyān/Ugāniyāns, but he never mentioned his field of study. In a short period of time, Uhāniyān wrote letters to Louis Lumière, Alexander Korda, Abel Gance, Frank Capra, Rouben Mamoulian, Vsevolod Pudovkin, and D. G. Phalke and announced to them that they had become honorary members of the International Federation of Scientific Research Societies, although none had made such a request.

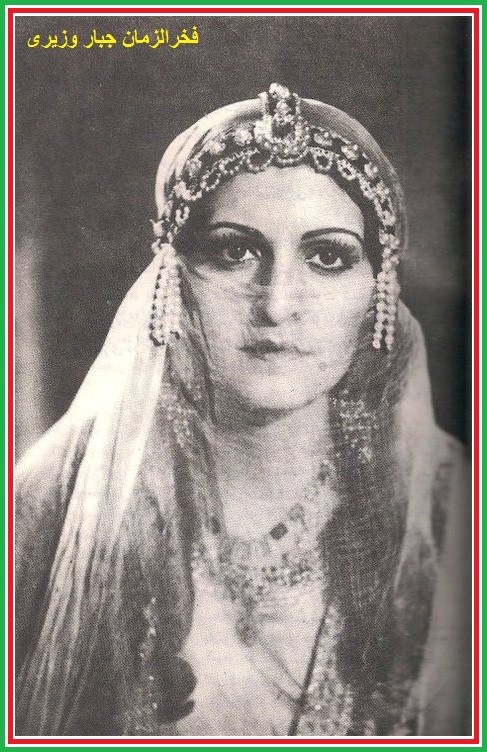

In February 1931, Uhāniyān returned to cinema and advertised for the second term of his Acting School. Just like the first term, the advertisement invited both interested men and women to register at the school. To solve the problem of the religious ban on men teaching women, Uhāniyān hired a woman to manage the female section of the school: Fakhr al-Zamān Jabbār Vazīrī, who later acted in the film Shīrīn u Farhād (Shīrīn and Farhād) directed by ‛Abd al-Husayn Sipantā.29This talking film was shot in 1934 in Bombay and was an adaptation of the love story of Shīrīn and Farhād written by Vahshī Bāfqī, the Persian poet in the tenth century A.H. A year later, in 1931, the names of the graduates from the second term were published in ‘Ittilā‛āt newspaper and it turned out that there were no women among them.30‘Ittilā‛āt Newspaper, Year 7, no. 1702, May 21, 1932. Uhāniyān had announced the number of graduates to be thirty-three, while only the names of eighteen people were published in ‘Ittilā‛āt.

Figure 7: A portrait of Fakhr al-Zamān Jabbār Vazīrī.

In those days, most of the Islamic clerics in Iran had forbidden watching films and acting in them. They considered the screening of films and performing music and theater as “tools for spreading the forbidden and promulgating debauchery.” They had thus issued a decree of excommunication for anyone who watched films or acted in them. It was Shaykh Fazl-Allāh Nūrī who banned watching films in cinema for the first time in circa 1907.31Mas‛ūd Mihrābī, Tārīkh-i Sīnimā-yi Īrān az Āghāz tā Sāl-i 1357 (Tehran: Nazar Publications, 2016), 11-12. Since then, Muslim clerics have not had a positive attitude towards cinema. This attitude helped Uvānis Uhāniyān find the subject of his second film.

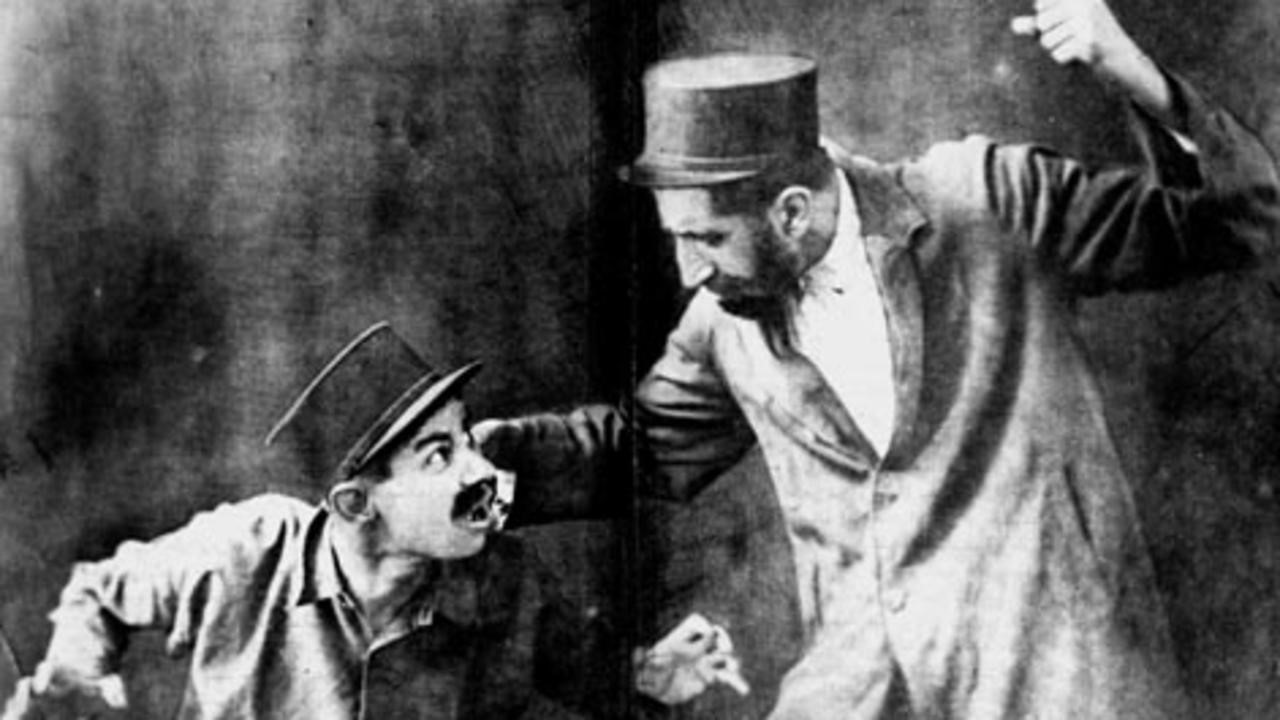

Hājī Āqā Āctur-i Sīnimā (Haji, the Cinema Actor), Uhāniyān’s second film, focuses on the issue of depicting religious men in cinema. The film is about a director who is looking for a new subject. One of his students called Parvīz tells him about an incident that happened to himself. Parvīz’s father-in-law works in the bazaar and is known as Hājī Āqā. Parvīz and his wife wish to be screen actors, but Hājī Āqā is against it. The director decides to make a film about Hājī and make him change his mind. With Parvīz’s help, he outlines a plan: Hājī’s servant is asked to steal his watch so that Hājī chases the thief, and the director follows him with his camera. At the end, they use a trick to make Hājī enter a movie theatre and he watches himself on the screen. At first, Hājī gets upset, but when the spectators find out he is present in the theater and clap for him, he is delighted and agrees that his daughter and son-in-law continue acting.

Figure 8: A still from the film Haji, the Cinema Actor, directed by Uvānis Uhānīyān, 1933.

To produce the film, Uhāniyān needed money and for the first time he put up all the shares of the film for sale. To raise the two-thousand-toman budget for the film, he divided this sum into forty shares of fifty tomans each and announced that anyone who wanted to do something good in cinema can buy a share and participate in the making of Haji, the Cinema Actor. He himself bought four shares and a police colonel named Maqāsidzādah-Furūzīn bought twelve shares. The entire budget was still not collected. Uhāniyān got creative again, and for the first time, he approached businesses and made them sponsor the film. A watch shop and a movie theater paid him to advertise for them, and he shot a part of the film for free at the newly-opened Café Pārs in Tehran.32Habīballāh Khān Murād, one of the film’s shareholders, played the role of Hājī Āqā.Habīballāh Murād (1906-1978) was one of the first actors and pioneering artists of Iranian cinema and the owner of Cinema Murād. In the 1950s, he appeared in Love Intoxication (1951), Mother (1952), Bīzhan and Manīzhah (1958) and Twins (1959). He owned Cinema Murād, too.

Selecting an actress for the leading role proved to be a problem. Uhāniyān intended to give this role to Fakhr al-Zamān Jabbār Vazīrī, but his close friends advised him against casting a Muslim woman in the film and warned him that it could spark harsh reactions from the hardliners and religious groups. As a result, he gave in and asked Āsīyā Qustāniyān, an Armenian actress who had formerly acted in a film in Egypt33Tahmāsb Sulhjū, “Bardāsht-i Avval,” Fārābī Quarterly 37 (Summer 2000): 151-172, quoted from 154. In Haji, the Cinema Actor, Uvānis Uhāniyān and Zimā, his nine-year-old daughter, also played short roles.

Figure 9: Āsīyā Qustānīyān in the film Haji, the Cinema Actor, directed by Uvānis Uhānīyān, 1933.

The cinematographer of this film was Paolo Potemkin, Khānbābā Mu‛tazidī’s assistant. The main problem in the production of the film, however, was the lack of a proper camera. The only camera that they had access to did not have an electric motor and someone needed to keep spinning the wheel on the side of the camera.

To avoid the constant spinning of the motor handle of the camera, Uhāniyān found an innovative solution. He asked a student, Kāzim Sayyār, from the Acting School who also worked as a tailor, to get him a sewing machine. He then attached the machine to the wheel of the camera to make it spin steadily and therefore solved the problem of the old camera.

But the budget shortage made the shooting of Haji, the Cinema Actor last for about two years. To provide the money, Uhāniyān turned to theater production, including a show that he called “live cinema.” On 12 September 1933, the ‘Ittilā‛āt published an ad for this show, announcing that Bachah-i Mafqūd (The Missing Child), directed by Uvānis Ugāniyāns, will be on stage for seven nights featuring forty-one artists of cinema and theater.34‘Ittilā‛āt Newspaper 1032, September 12, 1932.

Five months later, in February 1933, Haji, the Cinema Actor was ready for screening. The film premiered on 1 February 1933, for government officials and journalists at Cinema Royal.35‘Ittilā‛āt Newspaper, January 31, 1934. But the commentaries were mostly negative this time. The quality of the picture, which was either too dark or too bright, caused the most criticism.36Iran Newspaper 1341, February 5, 1934. The film was also a failure at the box office. Most historians believe that the screening of Dukhtar-i Lur (The Lur Girl), the first talking film in Iranian cinema, on 21 November 1933, was the main reason for the failure of Uhāniyān’s film since people were no longer pleased with silent movies.37Lur Girl, directed by Ardashīrkhān Īrānī, 1933, featuring ‛Abd al-Husayn Sipantā and Rūhangīz Sāmīnizhād. Uhāniyān’s second film was screened only thirteen days in Tehran. Most of the investors of the film complained to Uhāniyān for the low sales and even took the properties of the office of Pers Film Company as compensation. The only copy of the film was in the possession of Habīballāh Khān Murād, the lead actor and an investor of the film, and was not shown to anyone for years.

Uhāniyān was not disappointed by this failure. He was determined to work in cinema, and continued by developing the third term of his Acting School. But this term never took place. At the same time, in order to draw the attention of the Iranian officials to film production, he referred to the history of Iran in an article in the Iran newspaper and wrote that the best thing to do is to make films about the lives of poets and historical figures of the land, such as Firdawsī. The Firdawsī Millennial Celebrations were scheduled to be held in Tehran on those days.38Iran Newspaper, May 31, 1934. However, ‘Abd al-Husayn Sipantā, an Iranian in India, had already started making a film about Firdawsī’s life, and no one was willing to invest in Uhāniyān’s next film.39Firdawsī (1934), directed by ‘Abd al-Husayn Sipantā, Imperial Film Company of India.

For two years, Uhāniyān made several documentaries about the railway system and the Constitutional Revolution celebrations with the help of Khānbābā Mu‛tazidī and Paolo Potemkin. His family members reported that in this period, he staged a few plays, including an opera titled Parvānah (Butterfly).40Nīkūnazar, Ādam-i mā dar Bālīvūd, 82. although there are no records of the staging of this opera. It is likely that the report is only based on Uhāniyān’s words.

In 1938, Uhāniyān announced that he received an invitation from the Imperial Film Company in India to go there and make a film.41Jamāl Umīd, Tārīkh-i Sīnimā-yi Īrān 1279-1357 Sh. (Tehran: Rawzanah Publications, 1995), 53. First, he went to Ashgabat with his daughter to see his wife, Lydia. In addition to this meeting, Uhāniyān intended to start an acting school there,42Umīd, Tārīkh-i Sīnimā-yi Īrān, 53. but he was hindered by bureaucratic obstacles. Later, he claimed that he made a film called Gul va Īt Ulmāz in 1938 in Ashgabat, although, according to the archives of Turkman-Film, the Turkmenistan National Cinematheque, and the Russian Cinematheque, no such film has ever been made.

Uvānis Uhāniyān went to Calcutta, India, with his wife and daughter at the outbreak of World War II. Uhāniyān later claimed that he established an acting school in Calcutta.43Umīd, Tārīkh-i Sīnimā-yi Īrān, 53. He introduced himself as the president of the International Federation of Scientific Research Societies and granted honorary doctorates to Benoy Kumar Sarkar and Savitri Devi.44Benoy Kumar Sarkar had a Ph.D. in Economics but worked in different fields of social sciences. He was giving lectures at Calcutta University from 1925, focusing on extreme nationalism. Sarkar was trying to invite Hindu youths to fight against communists. Later, he became a proponent of the Nazis, argued that Adolph Hitler’s leading method was benevolent dictatorship, thus supporting the establishment of the Nazis in India. Savitri Devi’s original name was Maximiani Julia Portas. She had studied philosophy at the University of Lyon in France but was also engaged in political activities early on and was a member of Greek nationalist groups. She had become so interested in this group and their beliefs that she abandoned her French nationality and accepted Greek nationality. It was well-known that she had taken a trip to Palestine in her youth and upon her return, had become attracted to Nazi ideology. She was trying to make a connection between Hinduism and Nazism to attract young people to her thoughts and activities through her rhetoric. During the 1930s, Devi worked as an agent who gathered information about the English forces and gave them to the Germans. This aroused the English military’s suspicion as both figures were supporters of the Nazi ideology. The English officials assumed there was a connection between Uhāniyān and the supporters of Nazism.

Figure 10: Uvānis Uhānīyānhanians in India.

While sojourning in Calcutta, Uhāniyān took some classes in traditional medicine and claimed that he has received a medical license from the Calcutta Medicine School. Later, he said in an interview in Iran that he took some courses with Indian ascetics and mastered the properties of medicinal herbs.45‘Ittilā‛āt-i Haftigī, no. 831, 33.

But Uhāniyān wished to make a film in India and therefore went to Bombay alone. In order to draw the attention of Indian Parsis, he went to Sāzmān-i Līg-i Īrān (Iran League Organization) and presented diplomas and honorary doctorates to several members of the organization.46Iran League was one of the two organizations founded in 1922 by the Parsis of India. Its function was sending presents and financial aid to the Zoroastrians of Kerman and Yazd in Iran. Its founders were influential and wealthy Parsis living in Bombay, and the organization had an important role in building schools and hospitals in Iran. Uhāniyān made a speech at the degrees award ceremony and requested the Parsis of Bombay rescue cinema by investing in it and rivaling Hollywood.47Iran League Quarterly, October 1938. However, the Parsis of India demonstrated no interest in investing in a film by this director.

Figure 11: A poster showing Uhānīyān alongside Indian actors.

During his stay in Bombay, Uhāniyān used to introduce himself as the president of the Asian Film Academy. He also invented a device under the name Professor E. G. Uhāniyān. Called the “Uhāniyān System,” he claimed that the device made it possible to shoot a scene with twenty cameras and the sound could be synchronized in or outside the studio.48Umīd, Uvānis Ugāniyāns, 162-164.

In 1941, he was arrested and imprisoned in Bombay, India, for collaborating with the Nazis. The English authorities were suspicious of his relationship with ‘Abd al-Rahmān Sayf-Āzād, an Iranian journalist residing in Bombay, who was suspected of spying for the Nazis, and therefore arrested both Uhāniyān and Sayf-Āzād. Additionally, he was in trouble because of the honorary degrees he had presented to Sarkar and Savitri Devi. The English authorities kept him in prison for several months and released him after they realized that he was innocent. He later claimed that he had collaborated with the English authorities and invented a weapon that was the main factor in their victory over General Rommel in Africa. He said that to help the English in their war against the Nazis, he had designed a parachute to which gasoline could be injected through a pipe and explode when hitting the ground or soldiers.49‘Ittilā‛āt-i Haftigī, no. 831, 32.

Uhāniyān returned to Iran in 1951. This time, he was alone and had adopted the new name Rizā Muzhdah, claiming that he had converted to Islam. He was therefore known to different groups with different names Ugāniyāns, Uhāniyān, and Rizā Muzhdah. He opened a beauty salon in Tehran under the name Rizā Muzhdah and started treating baldness. Uhāniyān invented a medicine called “Bioherin,” which supposedly cured baldness. He also claimed to have made two other medicines, a pill called “Stomatin” which was meant for all types of gastrointestinal diseases, from stomachache to intestinal cancer, vomiting, constipation, and bloating. His other medicine was called “Romat,” which he claimed healed rheumatic fever, muscular rheumatism, arthritis, and even acne. But in 1953, several patients who had not been cured filed complaints against him at the Ministry of Health, and his license was revoked. From that time, Uhāniyān continued his work in secret and without a license.

But the thought of cinema never left him alone. In 1954, Uhāniyān announced that he was going to make a film called Savār-i Sifīd (White Rider) and published casting announcements in cinematic publications.50Sitārah-i Sīnimā (20 October 1954): 11. In order to show his determination in making this film, he even started shooting riding scenes in a desert without the main actors. The shooting stopped due to the uncertainty of the plot, the failed search for the main actor, and high production expenses. After that experience, Uhāniyān started moving away from cinema, although in 1960 he applied for financial aid from Iran’s Bureau of Radio and Advertisement to make a film called Rizā Shāh-i Kabīr (Reza Shah the Great).51Iran National Cinematheque Newsletter, no. 11-12, 192.

In the seven years after his attempt at making The White Rider, He spent most of his time treating patients. In 1957, he said in an interview that he was busy inventing various things. He claimed to have made a vertical take-off airplane called Parastū (swallow), and to have designed a bomber capable of flying nonstop for twenty-five hours at a speed of 1,500 kilometers per hour, with the ability to land on both land and sea. He also claimed to have designed a flying bus named “Autohydroplan” which would transport a large number of passengers, and stated that he was thinking about inventing flying saucers that could transport passengers at high speed.52‘Ittilā‛āt Weekly, no. 831, 33. These claims were met with different reactions. In the press, some people made fun of him and some people, including the guild of garage owners in Tehran, protested the invention of passenger flying machines as they argued it would lead to their unemployment. None of the alleged inventions came to fruition.

Until 1961, Uhāniyān was secretly practicing medicine and was engaged with his inventions. But on 23 June 1961, the Tehran Tax Office noticed that Uvānis Uhāniyān had not paid his taxes for any of his inventions, and they sent him a bill for sixty thousand tomans. Uhāniyān suffered a stroke after seeing the tax bill and died in the hospital a while later.53Umīd, Tārīkh-i Sīnimā-yi Īrān. 54.

Stories about Uhāniyān’s death are also inconsistent. Ārād, Uhāniyān’s first child from his second wife, believed that on the night of his death, his father had gone to the court to negotiate the production of his Parastū airplane, and when he returned from the court, he told him that he had been poisoned and died due to toxification.54Nīkūnazar, Ādam-i mā dar Bālīvūd, 142. However, Ashraf Karīmzādah, Uhāniyān’s second wife, believed that he had had a fight with his partner at his medical office, and had suffered the stroke as a consequence of stress.55The lack of clarity about the cause of Uhāniyān’s death led to increasing speculations of murder.Olga Kazak, “The Father of Iranian Cinema,” Armenian Cinema Museum, 2019, accessed 19/11/2024, www.armmuseum.ru/news-blog/ovanesiranfimfounder.

The inconsistent stories about Uhāniyān’s death resemble all the other aspects of his life. He lived and worked for almost sixty years under the names Uhāniyān, Ugāniyāns, and Rizā Muzhdah, and experimented with various jobs, including teaching, film and theatre directing, practicing medicine, making medications, and inventing army equipment. Ultimately, however, he is remembered in relation to cinema, as the founder of the first cinema school and the first filmmaking company, and the director of the first feature film in Iran.

Cite this article

This article explores the complex and enigmatic legacy of Uvānis Uhāniyān, the pioneering director of Iran’s first feature film and the founder of its first acting school for cinema in the early 20th century. It critically examines his contested history, disputed accomplishments, and eclectic career trajectory, which ranged from promising collaborations with Hollywood figures to ill-fated film ventures in India and, ultimately, detainment over alleged Nazi ties.

By tracing Uhāniyān’s cinematic foundations to his studies in 1920s Moscow and his early innovations in Turkmen cinema, the article situates his artistic ambitions within the broader evolution of Iran’s movie industry. A key focus is on his trailblazing yet financially unsuccessful works, such as Ābī o Rābī (1930) and Ḥājī Āqā Āktūr-i Sīnemā (1931), assessing how these films reflect his bold but commercially constrained vision. Through a reassessment of his contributions, this article seeks to unravel the contradictions and complexities of a figure both celebrated and overlooked in Iranian film history, positioning Uhāniyān as an audacious risk-taker whose groundbreaking efforts helped lay the foundations for Iranian cinema despite the challenges he faced.