A Simple Event

Introduction

This article offers an analysis of Suhrāb Shahīd Sālis’s debut film, A Simple Event (Yek Ettefaq-e Sadeh, 1973),1A Simple Event (Yek Ettefaq-e Sadeh), directed by Suhrāb Shahīd Sālis (Central Film Office of the Iranian Ministry of Culture, 1973). by exploring the complex themes of silence, duration (la durée), and minimalism, which contribute to the film’s narrative depth. The article also draws comparisons between recurring motifs in A Simple Event, such as daily routines and the theme of repetition, and the works of Albert Camus, specifically his essay “The Myth of Sisyphus” (1942) and his novel The Stranger (1942). Furthermore, the article provides a concise exploration of the historical context surrounding the film’s production, and Shahīd Sālis‘s background.

Figure 1 – Muhammad’s single rectangular house. Screenshot from the film Yek Ettefaq-e Sadeh (00:58:20).

A Simple Event displays life during the early 1970s in a depressing town nestled along the northern coast of Iran, where a ten-year-old boy named Muhammad lives alongside his helpless parents—an ill mother and a father who poaches and smuggles fish to make ends meet. Despite falling behind his school responsibilities, Muhammad assists his jaded father in his clandestine trade of forbidden fishing expeditions. Additionally, he assists his mother in their humble home—a single rectangular room (see figure 1)—by running errands and fetching water from a nearby well. Upon returning home from school each day, the boy’s diet of bread and kashk2Kashk is a traditional Persian food that is made from fermented dairy products. It is typically made from the whey of yogurt or cheese, which is strained and then dried to form a powder or a thick paste. Kashk has a tangy and slightly sour flavor. In Persian cuisine, kashk is used as a versatile ingredient in various dishes. It is commonly used as a topping or garnish for soups and stews. Kashk is also used as a base for sauces and dips, such as Kashk-e Bademjan (eggplant and kashk dip). In Sālis’s film kashk signals the lack of variety in Muhammad’s family’s food and their poverty. soup remains simple and monotonous. One night, Muhammad’s mother dies. His father displays a little more concern for him after his mother’s demise. Determined to express his affection, the father tries to buy a coat for Muhammad, but when the deal does not go through, the father leaves the store, and Muhammad follows him along the street. This simple storyline and the technical simplicity of Shahīd Sālis’s debut film belies its humanistic complexity.

Complexities of Simplicity

Suhrāb Shahīd Sālis’s A Simple Event is a carefully planned and directed film of Iranian New Wave cinema that deviates from conventional cinematic techniques by usually placing the camera in a fixed corner assuming the role of an observer, thus allowing the viewer to witness the unfolding events solely from the camera’s perspective. Shahīd Sālis’s own account of his filmmaking style is enlightening: “I make my films from the point of view of an observer and in this way, I allow my audience to judge for themselves.”3Tara Ostad-Agha, “Yek Ettefaq-e Sadeh, A film by Suhrāb Shahīd Sālis” NetNevesht, September 13, 2019, https://netnevesht.com/a-simple-event-review/ Accessed 10/18/2023 [Translated by the author]. In this manner, A Simple Event represents the situation of a family in northern Iran in the 1970s that is involved in mundane daily fixed actions. The only dramatic incident of the film is the death of the mother, and even this death is shown simply and devoid of emotional provocations. The main character of A Simple Event is the child Muhammad, whose life is intricately woven with the challenges of caring for his ailing mother and supporting his weary fisherman father. It seems that Muhammad is already old in his childhood. He is always on the run; he goes back home from the morning shift at school, buys bread and candies for his sick mother who is either in bed or sitting to wash dishes, eats simple foods, drinks tea and speaks a few words (see figure 2). Then he goes to a beach where his father fishes illicitly, smuggles the fish to a vegetable shop, takes the vendor’s money, goes to a tavern patronized by the same daily customers, and gives the money to his father. Then he goes back to school and comes home again. The only dialogue between the son and mother is when the mother coldly commands him to “go fetch water.”4A Simple Event, 00:22:32. The mother is usually asleep facing the wall. With her back turned to the home, she is unaware of and indifferent to her son’s life and education.

The film subtly portrays a predominantly masculine atmosphere, particularly through scenes set in a somber bar frequented by Muhammad’s father and many other tired-looking men. Notably, the portrayal of female characters in the film is quite sparse. With the exception of two nurses from the Ministry of Health who administer vaccinations to the students, the only female character focused on in the film is Muhammad’s mother who is predominantly shown involved in mundane activities like washing dishes, stirring the kashk soup, eating meals, or exhibiting signs of exhaustion.

Figure 2 – Muhammad’s mother prepares their repetitive meal of kashk soup. Screenshot from the film Yek Ettefaq-e Sadeh (00:21:14).

Although usually physically absent, Muhammad’s father urges his son to study when he returns home tired and drunk.5 A Simple Event, 00:24:39. This concern from the father, though minimal (and probably sarcastic), creates a closer bond between him and his son. However, when the mother is called to school due to her son’s lack of studying, she dismisses the issue, showing no care for her only child’s education or future by saying to them: “Do whatever you think is right!”6 A Simple Event, (00:39:29). It seems that her son’s educational status is not a concern for her and it doesn’t matter what fate her only child is facing.

Amidst the monotonous routine of Muhammad’s life, a simple-yet-could-be-tragic event occurs. Muhammad’s mother passes away quietly and the doctor casually announces her passing: “She’s already dead”7A Simple Event, 00:53:44. (see figure 3). But no tragedy strikes as they already have been living it and their dull lives continue to move forward. Muhammad’s daily life remains unaffected: he continues to wear his school uniform, and the father too wears his fishing clothes, showing their detachment from the mourning ritual of wearing black. The teacher’s response to Muhammad’s loss only amplifies the absurdity of the situation. “It’s alright, everyone eventually dies. It was God’s will. It’s alright.” he declares, attempting to provide solace!8A Simple Event, 01:01:16.

Figure 3 – The doctor checking Muhammad’s mother who had already passed away. Screenshot from the film Yek Ettefaq-e Sadeh (00:53:24).

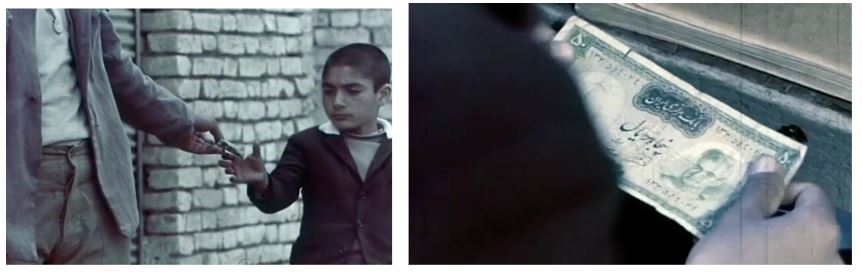

While Muhammad had tirelessly assisted his mother with household chores while she was alive, her death pushes him to follow his father and share his life. His father, a living embodiment of the sociopolitical production of a corrupt and unequal governing system, becomes his role model. It seems that the father’s feelings towards his son grow a little stronger after the demise of the mother. He gives him a fifty rial note (see figure 4), as a gesture of consolation, to “go to school and have lunch”;9A Simple Event, 00:57:11. later Muhammad seems to indulge in the simple pleasure of a sandwich and a soft drink, all the while with the same expressionless face.

Figures 4- Muhammad’s father gives him a fifty rial note, as a gesture of consolation after the demise of his mother. Screenshot from the film Yek Ettefaq-e Sadeh (00:57:11).

Even in the final scene, as Muhammad accompanies his father to go to a store to purchase a new suit, his lack of enthusiasm and anticipation remains palpable. However, the film poignantly portrays the harsh reality of their economic situation, as the price of the suit shocks Muhammad’s father to the extent that he abruptly changes his mind and exits the store.

The film’s empty and cold ambiance mirrors the emptiness that permeated Muhammad’s family members’ lives even before the mother’s passing. It appears that her demise only further dissolves into the void that already engulfs their existence. The film thus addresses the struggles faced by countless individuals who, like Muhammad, find themselves caught in the relentless cycle of poverty in the Second Pahlavi era (1925-1979) in Iran.

“But as soon as there are habits, the days become easy.”10Albert Camus, The Plague, trans. Stuart Gilbert (New York: Vintage-Random House, 1991), 7.

The essence of the essay “The Myth of Sisyphus”11Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1955). by French author Albert Camus (1954-1962) can be interpreted as the exploration of the absurdity of human existence and the importance of finding meaning and purpose in the face of an indifferent and chaotic universe. Camus uses the Greek myth of Sisyphus, who is condemned to endlessly roll a boulder up a hill, only to have it roll back down, as a metaphor for the human condition—a meaningless task whose mere accomplishment gives meaning to Sisyphus’s life and makes him happy! Instead of succumbing to despair or nihilism, Camus proposes that individuals can rebel against the absurd by embracing their freedom and creating their own meaning.

Similarly, in a seemingly mundane sequence of events, Muhammad remains unchanged, repeating the same actions over and over again, however, we do not see any impression of satisfaction on his face. As described above, his days are grounded in repetition: He hurries to school and then rushes to the shore to collect his father’s catch, which he subsequently sells at a vegetable store. With money in hand, he runs to a bar with a hazy atmosphere to the place where his father is usually standing for a drink to drown his despair in silence. Perhaps Muhammad and his family are, in a Camuesque way, plagued by time and the only medicines to sustain it are the habits of eating, going to school, drinking, sleeping, and their repetition. Shahīd Sālis beautifully displays this function of habits through different elements of setting, for example, the father’s repetitive visit to the tavern where he stands in a fixed place; the repeated presence of depressive customers in the tavern; the shot of the window at which Muhammad eats his meals of bread and kashk soup (see figure 5); and even the repeated frames in which Muhammad is shown running home or carrying the smuggled fish. This repetitive pattern starts and grows all through the film by the metaphorical presence of railroads and the sound of trains throughout the film.

Figure 5 – One of the repetitive elements in the film is when Muhammad sits at the same window to eat his regular meal of kashk soup. Screenshot from the film Yek Ettefaq-e Sadeh (00:09:56).

The first shot of the film shows Muhammad walking leisurely on the railway. He starts running away when the old railroad security guard shouts at him “go away!”12A Simple Event, 00:02:50. However, in this scene, he seems to be running on the spot without going forward. Shahīd Sālis’s choice of lens and cinematography engage us with the very theme of the film: A ten-year boy in a distant harbor in northern Iran with a problematic father who just runs but never moves forward (see figure 6).

Shahīd Sālis’s own account of this scene is worth mentioning in full:

I took the child who is walking next to the rail with a telephoto lens. As a result, it seems that the child is walking in place on the railroad, and in fact, he is walking in place all his life. It is like this now, and it will be like this later. In a standing position, he is walking in a direction and he does not even know which direction it is, and in my opinion, it will be the same in his adulthood.13Ostad-Agha, “Yek Ettefaq-e Sadeh,” September 13, 2019.

Figure 6 – Muhammad walking on railway tracks at the beginning of the film which seems as if he is walking but never moving forward. Screenshot from the film Yek Ettefaq-e Sadeh (00:02:18).

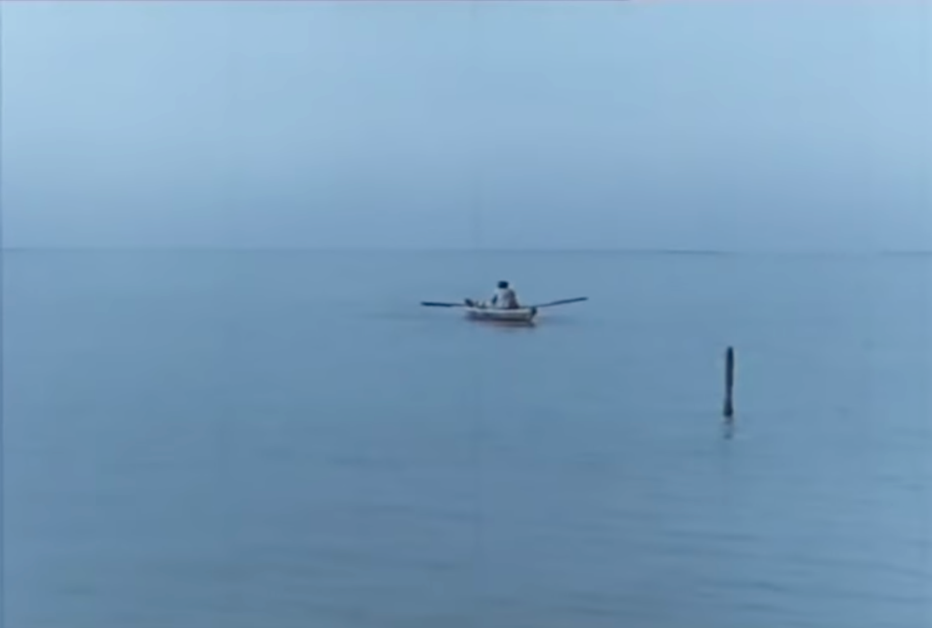

Similarly, in a later scene Shahīd Sālis shows the father navigating a boat (see figure 7). Muhammad is on the shore waiting for his father to come. From a distance, the boat appears to be a stationary object, while the waters beneath it flow in harmony with the wind. The father propels the boat forward by roaring the oars always in the same direction. This sequence serves as a poignant critique of a system within which the father is merely a passive figure without any future, without going forward. The son is left watching and waiting for his father in whose footsteps he will follow.

Figure 7 – Muhammad’s father navigates his boat which seems as if it is not moving forward. Screenshot from the film Yek Ettefaq-e Sadeh (01:08:56).

In Shahīd Sālis’s bleak film, the exploration of a young schoolboy’s alienation following the death of his mother goes beyond Meursault’s stark opening to The Stranger, “Maman died today.” Shahīd Sālis deeply explores the boy’s coming-of-age journey, showcasing his detachment through a consistent facial expression devoid of empathy, but filled with scorn and anger, as we the audience are led to assume. Shahīd Sālis highlights the passive nature of his characters, who find themselves pitted against a cruel and unequal system that has emotionally paralyzed them to the point of numbness and indifference. By minimizing dialogue among the characters, and conveying a lack of empathy and emotions among them, Shahīd Sālis underscores Muhammad’s alienation against the backdrop of a dry and often desolate setting. Muhammad is reminiscent of a protagonist in another work by Camus, the novel The Stranger. Camus’s novel criticized the existential absurdity of life at the time of World War II in Europe. Shahīd Sālis engages with the existential absurdity of a ten-year-old boy on the northern coast of Iran who lacks parental love and empathy, and whose family struggles with poverty. The Stranger follows the story of Meursault, a detached protagonist who is indifferent to societal norms. His inability to conform makes him an outsider, or stranger, in society. The novel challenges conventional notions of morality and justice, highlighting the meaninglessness of existence by raising questions about the nature of human existence and the search for personal authenticity in an indifferent world. Furthermore, similar to the Sisyphus addressed in Camus’s essay “The Myth of Sisyphus,” Muhammad is engaged in unremarkable habits and unemotional affects through which his life is reduced to a meaningless routine.

In a mesmerizing fusion of repetition, passivity, and silence reminiscent of some of Camus and Chekhov, Shahīd Sālis masterfully crafts a cinematic experience that explores the essence of human existence and its disaffection.

“Silence is the most perfect expression of scorn.”14 George Bernard Shaw, Back to Methuselah: A Metabiological Pentateuch (New York: Brentano’s, 1921), 255.

Philosophers of language such as Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein (1889-1951) and Martin Heidegger (1889-1976) have employed and discussed silence and its implications, whether mystical, literal, or political.In his seminal book Tractatus (1922), Wittgenstein attempts to formalize an approach to describing the ineffable, mystical (das Mystische) nature of language and what can and cannot be said: “What can be said at all can be said clearly, and what we cannot talk about we must pass over in silence.”15Wittgenstein cited in Louis S. Berger, Language and the Ineffable: A Developmental Perspective and its Applications (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2011), 23. The scholar of English literature Gerald Bruns refers to the late Heidegger’s thinking about language in which Heidegger “consistently and frequently gives listening and silence a strange priority over speaking: The unspoken is the true source of what is said… Stillness is something you can hear if you listen for it….. Language speaks as the peal of stillness… The peal of stillness is not anything human.”16Berger, Language and the Ineffable, 40. [Emphasis in original].

Notably, the contemporary implications of silence, especially in Western and Eastern literary texts go beyond mere unreadability and address more complicated themes such as psychoanalysis, history, and political thought. The scholar of comparative literature Jason Bahbak Mohaghegh discusses the relationship between these themes and silence and offers a comparative study of silence in the East—specifically in the work of modern Iranian authors such as Ahmad Shamlu, Sadegh Hedayat, and Forough Farrokhzad—and theories of the philosophers and literary scholars of the West such as Gilles Deleuze, Maurice Blanchot, and Gaston Bachelard.17Jason Bahbak Mohaghegh, Silence in Middle Eastern and Western Thought: The Radical Unspoken (New York: Routledge, 2013), xiv-xv. Mohaghegh argues that Deleuze’s philosophical interests often suggested the imperative of a “becoming-silence,” namely, a final threshold at which Being is dragged into flux and therefore has no recourse but to convey itself through indistinct articulations (nonsense, the stutter, the refrain). This becoming-silence can only execute its vitality in writing by forsaking the concept of the author, and thus opening the doors to a post-subjective orbit that privileges both multiplicity and singularity. It is at this stage, moreover, that literature seeks the instantiation of its own limit—a supra-linguistic juncture wherein the tyranny of expression ceases and the rein of the unspeakable begins.

One may argue, therefore, that silence is an element that refers to both the inability of human language in articulating the ineffable and to the display of its uncanny profoundness. Similarly, filmmakers may employ silence in film to enhance the visual storytelling and allow for a deeper engagement with the narrative and the psychology of the characters. Temporal silence is the most basic component that formally defines Shahīd Sālis’s film. For Muhammad, silence seems to be an expression of fear, disdain, and wordless rage echoing George Bernard Shaw’s understanding of silence as “the most perfect expression of scorn.” Muhammad’s face remains stoic, unaffected by any emotion, even in the face of the heart-wrenching loss of his mother. This unwavering facial impression is further exemplified as Muhammad maintains an apparently impassive expression when his father slapped him upon discovering that Muhammad had lost some smuggled fish during an encounter with Coast Guards.18A Simple Event, 00:34:08.

Suhrāb Shahīd Sālis’s meditative film can be described as a kind of cinema that eliminates the unnecessary and keeps the basics. This elimination extends to the use of silence as an (un)dramatic motif instead of the use of words and language. Added to this silence are the minimalized uses of numerous natural and mechanical sounds such as the barking of dogs and the continuous whistle of a passing train.

In Shahīd Sālis’s film, it is this concerted silence that pervades the small harbor throughout the movie, creating the impression of a sad, dull, and distant place reminiscent of films by several acclaimed filmmakers who also utilized silence as a thematic element to convey characters’ challenges with life. The Japanese filmmaker Yasujirō Ozu utilized minimal dialogue and silence in Tokyo Story (1953) to convey emotional depth; the Belgian filmmaker Chantal Akerman in Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) is known for employing deliberate pacing and the use of silence to convey the monotony and isolation of the protagonist’s life; the Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky in Stalker (1979) and Solaris (1972) utilized silence to allow the audience to immerse themselves in the atmospheric and philosophical themes; and the Italian filmmaker Michelangelo Antonioni in L’Avventura (1960) used silence to heighten the tension and ambiguity of the narrative.

However, due to significant resemblance, it seems that Shahīd Sālis’s was inspired by one of his favorite filmmakers, the French filmmaker Robert Bresson (1901-1999), who employed a notable style of minimal dialogue. Bresson is known for his minimalist style and intense focus on the psychological aspects of existentialism. With its slow visual rhythm, desolate scenery, simplistic visuals, and sparing conversations, Shahīd Sālis’s film bears a striking resemblance to Bresson’s film A Man Escaped (1956).19 In Bresson’s film A man condemned to death has escaped or The wind blows where it wants (“Un condamné à mort s’est échappé ou Le vent souffle où il veut”) is based on the true story of André Devigny, a French Resistance fighter imprisoned by the Nazis during World War II. The story follows Devigny’s meticulous and determined efforts to plan and execute his escape from the seemingly impenetrable prison. Bresson’s film focuses on the psychological and physical challenges faced by Devigny, highlighting his resourcefulness, resilience, and unwavering determination to regain his freedom. A Man Escaped is known for its minimalist style, precise storytelling, and intense portrayal of the human spirit’s struggle against oppression. Similarly, Shahīd Sālis’s unique blend of minimalism, lack of long dialogues, existentialism, and attention to detail in A Simple Event makes it contemplative, deeply humanistic, and for some, boring.

Furthermore, A Simple Event shares striking resemblances with the works of the Hungarian filmmaker Béla Tarr (1955-), particularly his masterpiece The Turin Horse (A torinói ló, 2011). Tarr is renowned for his distinctively slow approach to filmmaking, characterized by existential silences, extended shots, and minimalistic narrative. In The Turin Horse, Tarr portrays the monotonous and desolate existence of a rural father and daughter living in an isolated farmhouse alongside their horse. The horse serves as their sole means of survival and Tarr displays, in the course of six days, the gradual deterioration of the horse’s cooperation which threatens their very survival. Similar to Shahīd Sālis’s film, Tarr’s The Turin Horse employs atmospheric cinematography and deliberate pacing to convey the mundane routines of the father and daughter whose daily lives revolve around simple tasks, such as consuming potatoes as their primary food. Tarr’s film proceeds in full silence while A Simple Event excludes unnecessary dialogue and music to magnify the significance of the lack of human communication particularly between a mother and child living under the same roof. Throughout the entire movie, the conversations are incredibly sparse, consisting of brief sentences that often carry a sense of order and urgency. This is evident right from the start, when the old train station security guard coldly instructs Muhammad to “go away” as if society has abandoned him. Likewise, his parents’ constant commands to “turn off the light,“20A Simple Event, 00:09:23. “fetch water,“21A Simple Event, 00:22:32. “study,“22A Simple Event, 00:24:38. “close that door,“23A Simple Event, 00:25:34. “hey you, stand,“24A Simple Event, 00:31:13. “come closer,“25A Simple Event, 00:34:12. “Go and fetch the doctor,“26A Simple Event, 00:48:06. “wear this,“27 A Simple Event, 01:15:16. and “take it off,“28A Simple Event, 01:16:41. have alienated him to such an extent that more meaningful communication through words becomes impossible.

Each shot of both films is carefully crafted, often utilizing static camera positions and precise framing to create a visual harmony and a distinct internal pacing complemented by deliberate editing to sustain the slow flow. This technique creates a sense of immersion and allows the audience to experience the passage of time in a more realistic and contemplative manner. In addition to silence and minimal dialogue, the recurring motif in Tarr’s and Shahīd Sālis’s films is the depiction of bleak and desolate landscapes which mirror the inner turmoil and despair of the characters, emphasizing their isolation and the harshness of their existence. However, what truly binds these two films together is their shared exploration of existentialism and human suffering and their intertwinement of the mundane and disenchanted rituals of things like daily meals. Further, both films centrally employ silence and lack of empathy, as well as the immersive duration that is experienced by both characters and audience.

Although Shahīd Sālis’s focus is more on the power of silent impressions, there are also captivating visual elements at play. In particular, intense gazes are shared among the characters that hold deep significance, especially within Muhammad’s family, between Muhammad and his teacher, and even between his father and the tavern’s customers. Through these silent exchanges of gazes, a series of hidden emotions such as fear, passivity, and anger are magnified, deepening the complexity of the characters’ feelings (see figures 8, 9, 10).

Figure 8-9- The exchange of silent gazes between Muhammad and his father in the tavern where his father for the first time in the film buys him food after the demise of his mother. Figure 8 (Left)- Screenshot from the film Yek Ettefaq-e Sadeh (01:13:33). Figure 9 (Right)- Screenshot from the film Yek Ettefaq-e Sadeh (01:13:38).

Figure 10- Muhammad’s silent gaze when an educational representative asks him a question but he does not know the answer and stays silent. Screenshot from the film Yek Ettefaq-e Sadeh (00:31:13).

Minimalism: Less Is More

In his minimalism, by casting non-professional actors, Shahīd Sālis injects a raw and authentic quality into his films, aiming for a subdued and naturalistic acting style. Rather than relying solely on visuals or dialogue, Shahīd Sālis employs sound in a subtle and minimal manner to convey emotions and meaning, often incorporating off-screen sounds and ambient noises to enhance the realism and emotional impact of a scene. For example, the gentle Torkaman lullaby over the opening credits delicately weaves its way into the narrative, by setting the stage and addressing the significance of motherly love in a child’s flourishing. Ironically, this poignant melody seems to serve as a reminder of what Muhammad’s life lacks. The film’s soundtrack is made of sporadic dissonant piano notes, each struck by Shahīd Sālis to vent his anger by striking a piano key at the Ministry of Culture and Arts. Omid Rouhani remembers that these nondiegetic piano notes were recorded to be used later as the film’s soundtrack.29“Omid Rouhani’s memories of his friendship with Shahīd Sālis – How “A Simple Event” was made” Farhikhtegan Newspaper, September 12, 2022. https://farhikhtegandaily.com/news/74272/«یک-اتفاق-ساده»-چگونه-ساخته-شد؟/ [Translated by the author]. The September 10, 2022 meeting of “Pine Art House Saturdays” was dedicated to showcasing and analyzing Suhrāb Shahīd Sālis’s film A Simple Event. Omid Rouhani, an Iranian film critic and actor who collaborated with Suhrāb Shahīd as one of the script writers, was invited to share the experience of their collaboration. Rouhani provided insights into the making of the film and the intellectual climate of that era. Notably, although Shahīd Sālis explores the mundane and melancholic aspects of a certain kind of life, with “everyday routine” being a central theme, the film’s minimalism and universal humanistic theme transcends the specificity of his protagonists and offers a broader reflection on the human condition. According to Golbarg Rekabtalaie, “In the words of A. H. Weiler (1975), an editor and critic from the New York Times, ‘the documentary-like authenticity’ of the film portrayed the global ‘tragedy of isolation, poverty, and hopelessness’ localized in ‘the daily life of a [ten year old] boy’ in an Iranian hinterland.”30Golbarg Rekabtalaie, “Cinematic Modernity: Cosmopolitan Imaginaries in Twentieth Century Iran” (PhD diss., University of Toronto, 2015), 218. Accessed July 3, 2023. https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/69444/3/Rekabtalaei_Golbarg_201506_PhD_thesis.pdf

In Senses of Cinema Peter Hourigan equally praises the universalism of the theme of Shahīd Sālis’s film: “This ‘simple’ life is observed with a quiet, dispassionate gaze that at the same time is saying this is a life worth observing, because it simply is a life. There is also a degree to which this quiet observation is saying so much more about life and society in Iran, and by extension the whole world, than any polemical piece of filmmaking.”31Peter Hourigan, “Memories and Confessions of a Visit to Il Cinema Ritrovato,” Senses of Cinema, September 14, 2015. http://www.sensesofcinema.com/2015/festival-reports/memories-and-confessions-of-a-visit-to-il-cinema-ritrovato/

The minimalist and contemplative approach to filmmaking by Shahīd Sālis inspired and influenced the renowned Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami. However, Kiarostami’s cinema was fortunate enough to garner attention, analysis, and admiration from a wider international audience, thanks to its exceptional reception at foreign film festivals, notably the Cannes Film Festival in 1997 which granted Kiarostami the Palme d’Or (Golden Palm) award for his remarkable film Taste of Cherry (1997).

Influence on Kiarostami

Although Abbas Kiarostami’s documentary-like style of filmmaking was influenced by Shahīd Sālis’s cinema of slow rhythm with minimalist aesthetics, the comparison between Kiarostami’s and Shahīd Sālis’s styles misses an elusive difference. Kiarostami’s visual lyricism and subtle humor makes his cinema less alienating and more humanistic. Both Kiarostami’s films and Shahīd Sālis’s films often allow viewers to immerse themselves in the characters’ internal struggles and existential dilemmas. In Shahīd Sālis’s particular cinema of minimalism and elimination, the setting feels apocalyptic. This marks a difference from the lingering and attachment to remnants present in Kiarostami’s contemplative style which subtly sanctifies everyday life, as well as the timeless beauty of nature. In Shahīd Sālis’s case, particularly in A Simple Event, it also showcases the vulgarity that exists within everyday life (addressed by repetitive display of the acts of drinking, eating, and sleeping). In Muhammad’s village, contrary to the expectations of contemporary audiences who are used to the blissful pastoral image of Iran in Kiarostami’s films (sometimes amidst a human tragedy like an earthquake), there is a severe lack of intimacy and communication among the villagers especially among Muhammad’s family at the center of the film.

La Durée

Robert Bresson’s minimalist and highly controlled style often emphasized the concept of “la durée” or duration (literally, the subjective experience of time) that the French philosopher Henri Bergson (1859-1941) termed as such. Accordingly, the duration of a shot is crucial in conveying the essence of a scene or character. Bresson usually aimed to capture the essence of reality by allowing the audience to experience time in a more authentic and contemplative manner.

Shahīd Sālis’s film is similarly an example of “duration,” which highlights the separation between humans and their environment encapsulated in sequences of film. In A Simple Event and his second film Still Life (1974), Shahīd Sālis uses long takes and extended durations of shots as a common technique. Shahīd Sālis prolongs the duration of a shot to allow the audience to immerse themselves in the scene, to observe the characters and their actions more closely, and to reflect on the emotions and meanings conveyed. This deliberate pacing and duration also creates a sense of tension and anticipation, as the audience is forced to wait for the resolution or outcome of a particular scene.32For example, in Bresson’s film Au Hasard Balthazar (1966), the duration of shots is often extended to capture the mundane and repetitive aspects of life. This approach allows the audience to empathize with the characters and their struggles, as they experience the passage of time alongside them. The extended duration also serves to heighten the emotional impact of certain scenes, such as the suffering of the titular donkey, Balthazar. See Robert Bresson, dir. Au Hasard Balthazar (Argos Films. Athos Films. Parc Film, 1966), Film.

Shahīd Sālis’s emphasis on duration is also created through his use of non-professional actors who were not trained in traditional acting techniques. The extended duration of shots allowed these non-professional actors to authentically inhabit their characters more fully, as they were given the time and space to express themselves naturally.

Consequently, Shahīd Sālis’s decoupage is extremely static, with shots and angles that remain consistent without intending to follow the characters. The camera assumes the role of an unobtrusive observer, capturing the mundane events and lackluster human connections within the family. Usually, these shots are notably long, stretching time and avoiding fast cuts, as the director aims to convey a sense of stretched lagging moments, manipulating the viewer’s perception of time.33Henri Bergson’s concept of “duration” (or la durée in French) is a central idea in his philosophy. Explained in his book Time and Free Will (1889), duration refers to the subjective experience of time, distinct from objective, measurable time. In his thesis Creative Evolution (1907) included in Henri Bergson: Key Writings (2014) Bergson writes, “Duration is the continuous progress of the past which gnaws into the future and which swells as it advances” (211). He emphasizes that duration cannot be fully grasped through rational analysis or scientific measurement, as it is a deeply subjective and intuitive experience, which challenges the traditional view of time as a linear sequence of moments, highlighting the importance of lived experience and the fluidity of time. Understanding duration offers insight into human consciousness and reality. See Henri Bergson, “Creative Evolution,” in Henri Bergson: Key Writings, eds. Keith Ansell Pearson and John Ó Maoilearca (London and New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2014), 211. Through this decoupage, the audience is able to grasp the distant and detached nature of the relationships between the characters, particularly within Muhammad’s familial context.

This static decoupage is seen in various scenes throughout the film. For instance, when the son dutifully brings water to the house, the fixed dinner meals, the father’s daily routine of fishing, and visiting the tavern. These repetitive and predictable actions can serve as a harsh critique, highlighting the profound impact of societal and economic stagnation on individuals’ progress and their daily lives.

Historical Context

Although Shahīd Sālis joined Iran’s Marxist party Hezbe Tudeh in 197834Ali Amini Najafi, سالگرد شهیدثالث، شورشی نومید [“Shahīd Sālis’s Anniversary, A Desperate Rebel,”] BBC PERSIAN. com, July 30, 2008. https://www.bbc.com/persian/arts/story/2008/07/printable/080703_la-rm-aa-shahid-saaless (one year before the 1979 Revolution), A Simple Event, which was made in 1973, has certain strong sociopolitical implications in defense of marginalized workers that must be addressed.35Hezbe Tudeh, also known as the Tudeh Party of Iran, is a political party in Iran founded in 1941. Tudeh was a prominent force during the early years of Iran’s post-revolutionary period. The party initially gained popularity by advocating for workers’ rights, social justice, and nationalization of industries. Backed by the Soviet Union during the era, Hezbe Tudeh emerged as a formidable adversary against the encroaching dominance of US imperialism in Iran. Hezbe Tudeh played a significant role in the nationalization of Iran’s oil industry in the early 1950s, supporting Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh’s efforts to assert Iranian control over the country’s oil resources. However, after the 1953 coup d’état orchestrated by the United States and the United Kingdom, which overthrew Mossadegh and reinstated the Shah’s regime, Hezbe Tudeh faced severe repression. During the rule of Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, Hezbe Tudeh was banned, and its members were subjected to persecution, imprisonment, and torture. Despite this, the party continued to operate underground and played a role in organizing protests and resistance against the Shah’s regime. During the 1979 Iranian Revolution, Hezbe Tudeh initially supported the revolutionaries and hoped for a democratic and socialist Iran. However, as the Islamic Republic under Ayatollah Khomeini consolidated power, Hezbe Tudeh faced increasing repression once again. Many of its members were arrested, and the party was severely marginalized by 1982. In recent years, Hezbe Tudeh has become virtually non-existent. Nevertheless, within Iran’s political sphere, there are still a few political activists and marginalized factions leaning towards the left, striving to reclaim their significance through engagement in political endeavors and protests. Their primary objective is to champion democratic reforms, social justice, and the rights of workers. However, these individuals often encounter formidable obstacles as a result of government constraints and oppressive measures. See Maziar Behrooz, “The Tudeh Party in Iran: A Historical Analysis,” Iranian Studies 34, no. 3/4 (Summer-Fall 2001): 265-288. Shahīd Sālis made A Simple Event during the period of the second Shah of the Pahlavi dynasty, Mohammad Reza Shah (1941 to 1979) at a time when the Shah planned large-scale technological modernization which I call prosthetic modernization. The Shah started investing mainly in economic and technologic progress rather than improving sociocultural infrastructures. The concept of prosthetic modernization addresses a situation where a society focuses primarily on modernizing its technological systems without adequately addressing or developing the cultural, sociopolitical, and human aspects of that society such as promoting democracy and diversity of political parties. In this context, prosthetic can be understood as an artificial or external addition that is meant to enhance or replace a natural function. The concept implies that the technological advancements are being treated as a substitute or quick fix for societal progress, without considering the broader sociopolitical implications and democratic needs of the community. The shah’s neglect of these aspects led to imbalances, inequalities, and a lack of sustainable development that would extend beyond the large cities and include smaller rural areas too. For example, a contemporary society that focuses solely on building advanced infrastructure, such as high-speed internet or transportation systems, without investing in democracy, equity, education, healthcare, or social welfare programs, may experience a disconnect between the technological advancements and the well-being of its citizens which can result in a digital divide, social unrest, or cultural erosion.

In 1971, two years before the production of A Simple Event, the boastful shah had already started celebrating the 2,500-year anniversary of Iranian Empire with a flashy expensive historical gesture while many marginalized populations of Iranians were struggling with poverty and lack of development.36In 1971, Mohammad Reza Shah, who proudly declared himself the “king of kings,” commemorated the remarkable 2,500-year legacy of the Persian monarchy by orchestrating an unparalleled celebration, destined to become arguably the grandest festivity ever witnessed in history. The event was known as the “2,500 Year Celebration of the Persian Empire” or the “Persepolis Celebrations,” a grand and elaborate festival held in Persepolis, in Shiraz, an ancient city in the southwest of the remains of Persepolis which was once the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire. The festival aimed to commemorate the long history and cultural heritage of Iran, particularly the Persian Empire, which was founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BCE. The Shah intended to showcase Iran’s rich history and position the country as a modern and progressive nation. The celebrations included various events and performances, such as parades, theatrical productions, traditional music and dance performances, and exhibitions of historical artifacts. The Shah invited numerous foreign dignitaries and heads of state to attend the festivities, which lasted for several days. Although the 2,500 Year Celebration of the Persian Empire can be seen as a significant event in Iran’s history, it also faced criticism for its extravagant nature and the shah’s attempt to associate himself with the glory of ancient Persian kings. The festival took place a few years before the Iranian Revolution of 1979, which led to the overthrow of the shah’s regime and the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran. For more information on this topic, see: “Decadence and Downfall in Iran: The Greatest Party in History” Real Stories (November 1, 2020). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dWxwtILhfvE; Ali Rahnema, The Rise of Modern Despotism in Iran: The Shah, the Opposition, and the US, 1953–1968 (London: Oneworld Academic, 2021). Meanwhile, during the second Pahlavi period, Iran was grappling with the forces of global capitalism, leading to a reshaping of the class system within Iranian society. Rather than reacting to this influx of modernity in a reactionary manner, Shahīd Sālis, as a critical filmmaker, explores the intended and unintended consequences of this transformation. He focuses on the marginalized individuals who were rejected and stripped of their dignity within these new societal structures. While the Shah’s regime proudly flaunted the 2,500-year legacy of Persian monarchy and showcased the wealth generated from oil money exported to the West, Shahīd Sālis exposes the dark underbelly of social and political developments that unfold within the silent classes of society.

Within this context, Shahīd Sālis‘s focus on the ordinary lives of everyday people, particularly those on the margins of society, adds a layer of authenticity and social commentary to his work. Shahīd Sālis brings attention to the often-overlooked aspects of society and provides both a display of, and a voice for, those who are marginalized. Accordingly, his film offers a form of social criticism, specifically targeting the expensive impositions of shallow prosthetic modernization. A Simple Event is a subtle critique of the political and economic situation in Iran during the second Pahlavi period. For example, Shahīd Sālis’s subtle cynicism about the nature of the corrupt system is evident when the educational representatives visit Muhammad’s classroom to assess the students and teachers. In one instance, the teacher instructs a student to recite a heartfelt piece about Iran and its rich culture37A Simple Event, 00:29:47. despite the Iranian audience knowing that it may not be entirely truthful. This hypocrisy is further highlighted in another scene, where a child exchanges a cigarette with Muhammad to mimic the act of smoking. Suddenly, the child’s father emerges from the corner and reprimands him for his wrongdoing. Within seconds, the father wears dark sunglasses and walks with a cane, pretending to be blind, while abusing his child as a prop to beg for money (see figure 11).

In another classroom setting, two nurses from the Ministry of Health paid a visit to Muhammad’s class with the purpose of vaccinating both the students and their teacher. As they carried out their vaccination duties, another cynical scene unfolds, we see a famous line from Persian poetry: گنج خواهی در طلب، رنجی ببر “If you seek treasure, you need to afford suffering”38A Simple Event, 01:08:10. is written on the blackboard echoing Shahīd Sālis‘s ironic tone against the educational system (see figure 12). This verse serves as a rallying cry for prosperity achieved through hard work, akin to the well-known English adage: “No Pain, No Gain.” However, the bitter irony becomes apparent when we realize that it is the ordinary people of Iran who bear the brunt of suffering, while a corrupt system shamelessly reaps all the treasures!

The theme of subtle social critique is visually induced in another scene in which Muhammad and his father walked back home from visiting the mother’s tomb. The father and son pass through the cemetery’s open gates that stand tall, similar to prison bars, yet in a wide-open space (see figure 13). This sequence serves as a visual metaphor, symbolizing Muhammad’s journey alongside his father, as they traverse a seemingly open prison. In a beautifully monotonous style, the film explores the idea that individuals are powerless in the face of societal expectations, something that runs against the grain of the commercial films of the time.

Shahīd Sālis’s cynicism permeates his mise-en-scene again as the film concludes, depicting Muhammad trailing behind his father as they traverse a desolate, sprawling boulevard adorned with the emblem of Iran Gas (see figure 14), symbolizing the paradoxical state of Iran and its inhabitants—the stark contrast between the nation’s abundant oil and gas reserves and the lack of progress, well-being, and equity in its rural regions.

While the regime focused on materialistic and economic advancement as the key elements of modernization, Shahīd Sālis took a different approach and dipped into the aftermath of these rapid developments, shedding light on the horrors and paralyzing consequences they brought about. In an apparently undramatic way, Shahīd Sālis portrayed the struggles of those who were marginalized and overlooked amidst this dislocated modernization, individuals who were unprepared for such grandiose changes. Through his seemingly unassuming and apparently undramatic style, Shahīd Sālis challenged the narrow and partial image of progress projected by the shah’s regime and explored and displayed the realities of everyday life for many Iranians, particularly those living in rural areas and small towns.

Shahīd Sālis’s Background

It is likely that Shahīd Sālis’s exploration of existential themes was influenced by his own sense of alienation during his upbringing outside of Iran in Europe. As the Iranian critic, actor, and Shahīd Sālis’s cowriter Omid Rouhani remembers, “Suhrāb grew up in an unstable family.”39 “Omid Rouhani’s memories of his friendship with Shahīd Sālis – How “A Simple Event” was made.” Suhrāb Shahīd Sālis was born in 1944 in Iran. His passion for filmmaking led him to pursue formal training at the School of Film and Television in Vienna, which he later completed at Institut des hautes études cinématographiques (IDHEC) in Paris. Prior to his 1973 debut feature film, A Simple Event, Shahīd Sālis had already established himself as a talented filmmaker through the making of over twenty shorts and documentaries in Iran which were disliked by the government due to their sociopolitical criticism.

A Simple Event, shot in a mere ten days with a very modest budget, exceeded all expectations by winning the esteemed Grand Prize at the Second Tehran Film Festival.40In following years, Shahīd Sālis’s film won the Interfilm Award and the Prize of the Ecumenical Jury at Berlin International Film Festival (1974). It has been screened in several other film festivals such as the Locarno International Film Festival (1974 & 1988); International Film festival Rotterdam (1975); and Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival (2019). This recognition solidified Shahīd Sālis‘s position as one of the prominent figures in New Wave Iranian Cinema of the early 1970s. His second Iranian feature, Still Life (1974), has since become a revered classic and has been showcased multiple times at international festivals and venues such as Pacific Film Archive.

According to the Iranian film critic, actor, and cowriter of A Simple Event, Omid Rouhani, upon completing his studies in Europe, Shahīd Sālis ventured to Iran in 1969 and found employment in the Ministry of Culture and Arts. Over the course of four years, he dedicated himself to creating short cultural documentaries in the northeastern cities of Iran. However, it wasn’t until 1973 that he was granted the opportunity to bring his own script to life in a twenty minute film. Accompanied by the Ministry of Culture team and armed with approximately one hundred minutes of negative at his disposal, Shahīd Sālis set off for Bandar Torkaman, the location of A Simple Event. Rouhani adds, “The script was written in just two nights, as it contained minimal dialogue that was conveyed to the actors on set.”41“Omid Rouhani’s memories of his friendship with Shahīd Sālis – How “A Simple Incident” was made.” As Rouhani’s accounts of his friendship and collaboration with Suhrāb Shahīd Sālis shed light on the conditions of the film’s production, it is worth quoting his report of this event at length. Rouhani continues, “Suhrāb had a clear preference for non-professional actors, believing that they portrayed reality better than professional actors who performed under ideal circumstances. Suhrāb cast Muhammad’s parents, teachers, manager, school attendant, store man, and others from the local community who willingly participated without any expectation of payment… We engaged in constant brainstorming sessions, sometimes leading to disagreements. On the last day of March 1973, a group of eight individuals traveled to Bandar Torkaman to bring this film to life, completing the entire production within two weeks. The film embraced a harsh and dreamless realism, deliberately maintaining a slow pace. We never intended for this movie to be purely entertaining, fully aware that it would provoke strong reactions from audiences. All the actors in the film were locals, and it was one of the few works of that period to feature on-set sound recording, as we opposed dubbing. We aimed to strip away any unnecessary cinematic elements, such as makeup, lighting, design, and even dramatization, in order to create an entirely dry film, even in its execution and budget. It was an extremely minimalistic movie, at a time when minimal cinema was not yet a prominent concept. Our objective was to explore the extent to which the gap between cinema and reality could be bridged.” Rouhani concluded by discussing the prevailing intellectual climate of the time, stating, “During those years, all intellectuals were opposed to the government, and discussions about the left were not common. The focus was on challenging the status quo. We aimed to revolutionize the world of art, presenting this dry reality in the most bitter manner possible, juxtaposed against a fake and hypocritical world.” He also touched upon the failed collaboration between Kiarostami and Shahīd Sālis, revealing, “Kiarostami had a script about a love affair in Berlin and sought an Iranian actor fluent in German. He asked me to portray Shahīd Sālis in that film, but I advised him to abandon the idea, as their collaboration would not have been fruitful.” Despite being given the resources to shoot five takes of each scene, Shahīd Sālis chose to defy convention and managed to save enough negative to make a feature film.

In 1975 Shahīd Sālis decided to relocate his filmmaking endeavors to Berlin where he crafted Far from Home (In Der Fremde, 1975). In the following years he made 12 films in Germany, some of which were successful in international festivals and won awards: Time of Maturing (Reifezeit, 1976), and Diary of a Lover (Tagebuch Eines Liebenden, 1977), a feature-length documentary film about Anton Chekhov (Shahīd Sālis’s favorite writer), titled Anton P. Checkov: A life (1981), as well as Utopia (1982) and Red Flowers for Africa (1991). Each of these films garnered critical acclaim and were featured prominently at numerous international festivals, further establishing Shahīd Sālis as a filmmaker of great talent and vision.42For a more detailed biography of Suhrāb Shahīd Sālis, see: Paradis Minuchehr, “Shahīd Sālis Suhrāb,” in Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, 2023. Accessed July 11, 2023. https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/shahid-saless-sohrab Shahīd Sālis left Germany to join his family in the United States in 1992. On July 1, 1998, Shahīd Sālis’s life journey was tragically terminated by a chronic liver illness that he had suffered throughout his life.43Suhrāb Shahīd Sālis’s later films often reflect his own personal experiences of exile, as he himself was forced to leave his homeland and navigate the challenges of living in a foreign land. Through his unique perspective, Shahīd Sālis captures the essence of this exilic journey, portraying the profound sense of displacement, longing, and alienation that accompanies such an experience. To gain a comprehensive understanding of Shahīd Sālis’s filmmaking and his journey both as an existentially exilic filmmaker and a displaced subject/filmmaker, see: Hamid Naficy, “Cosmopolitan Accented Cinema,” A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 2: The Industrializing Years, 1941-1978 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012): 500-512.

Conclusion

This article briefly explored how the themes of silence, duration, and minimalism contributed to the narrative depth of Suhrāb Shahīd Sālis’s debut film, A Simple Event. By drawing comparisons between recurring motifs in A Simple Event, such as daily routines and repetition, and their similarity in the works of Albert Camus, Robert Bresson, and Béla Tarr the article also highlighted the existential underpinnings of the film. The existential theme in A Simple Event and the works of the above-mentioned authors and filmmakers allows these authors and filmmakers to explore questions of grief, fear, anger and alienation. In addition, Shahīd Sālis’s precision and rhythm, his meticulous attention to detail and precise compositions cultivate this theme. Like his European ancestor Robert Bresson, rather than focusing solely on the action itself, Shahīd Sālis places emphasis on the process or duration of an action to further show and emphasize the characters’ conditions. Consequently, the characters’ performances highlight the significance of small gestures, gazes, movements, and details that unveil the inner thoughts and emotions of these characters. Finally, to better analyze, perceive and appreciate Shahīd Sālis’s directorial debut, this article provided the historical context surrounding the film’s production and Shahīd Sālis’s background as foundations that need to be considered.