The Aesthetic of Reality: The Poetry of Cinema in Muhammad Rizā Aslānī’s Films

Figure 1: Portrait of Muhammad Rizā Aslānī

Introduction

Muhammad Rizā Aslānī is a prominent Iranian filmmaker whose work holds a unique place in Iranian documentary and fiction cinema. He exhibits a sensitivity to history and traditions but with a specific perception about these two issues (history and traditions). In the Iranian cinema community, he is best known for his documentary films. However, he has emphasized that being labeled a documentary filmmaker is a “cliché and a misperception.”1Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, interview by Nematollah Fazeli and Mani Kalani in Chashm-andāzhā-yi farhang-i mu‛āsir-i Īrān, vol. 3 (Tehran: Pazhūhishgāh-i Farhang, Hunar va Irtibātāt, 2020), 178-179. Vice versa, he has, in fact, made more fictional films than documentaries, including television series such as Samak the ‛Ayyār (Samak-i ‛Ayyār, 1974) and Dust of light (Ghubār-i Nūr, 1996), as well as short films such as Badbadah: The Story of the Boy Who Asks (Badbadah: Dāstān-i pisarī kih mī-pursad, 1969), produced with the support of the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults (Kānūn-i Parvarish-i Fikrī-i Kūdakān va Nawjavānān). His notable feature films, The Green Fire (Ātash-i Sabz, 2007) and Chess of the Wind (Shatranj-i Bād, 1976), stand out among his non-documentary works.2Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, interview by Nematollah Fazeli and Mani Kalani in Chashm-andāzhā-yi farhang-i mu‛āsir-i Īrān, vol. 3 (Tehran: Pazhūhishgāh-i Farhang, Hunar va Irtibātāt, 2020), 178-179.

Although Aslānī distinguishes between his documentary and fictional films, he does not recognize a clear boundary between the two genres, at least not in the conventional sense.3Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, interview by Nematollah Fazeli and Mani Kalani in Chashm-andāzhā-yi farhang-i mu‛āsir-i Īrān, vol. 3 (Tehran: Pazhūhishgāh-i Farhang, Hunar va Irtibātāt, 2020), 178. Aslānī states, “what matters is creating a film, and through it, communicating and expressing something meaningful.”4Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, interview by Nematollah Fazeli and Mani Kalani in Chashm-andāzhā-yi farhang-i mu‛āsir-i Īrān, vol. 3 (Tehran: Pazhūhishgāh-i Farhang, Hunar va Irtibātāt, 2020), 179. The question is, given Aslānī’s sensitivity to Iran history, what is this “something ” that he is trying to convey through his films? He has, in fact, directly responded to this question:

[As a response] the documenting of the collective memory […] I do not seek to guide anyone, as no one [in Iran] is helpless or in despair in this regard. I establish my own version of documentation, meaning that at least one person—myself—can assert that this country and its people should not be manipulated or misrepresented. These Documentations [show] the sagacity of the people. I am not here to guide or assist, as I am neither a preacher, teacher, nor prophet. Instead, I walk alongside the people, acting as a keenly observant, moving and illustrated witness. I depict the lives of the people of this land, but they are neither passive nor unintelligent. For this reason, unlike most Iranian films, you will never find an unintelligent character in mine.5Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, interview by Nematollah Fazeli and Mani Kalani in Chashm-andāzhā-yi farhang-i mu‛āsir-i Īrān, vol. 3 (Tehran: Pazhūhishgāh-i Farhang, Hunar va Irtibātāt, 2020), 197-198.

Thus, in his films, whether they are considered documentaries or fiction, Aslānī portrays the intellectual capacity, wisdom, and thoughtful nature of the Iranian people. The unique forms of historical representation that Aslānī creates do not adhere to traditional historical records, such as those concerning the life of Safavīd Shah ‛Abbās I, or documents on Iranian customs, rituals, and festivals.6Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, interview by Nematollah Fazeli and Mani Kalani in Chashm-andāzhā-yi farhang-i mu‛āsir-i Īrān, vol. 3 (Tehran: Pazhūhishgāh-i Farhang, Hunar va Irtibātāt, 2020), 204. Instead, they are artistic and intellectual portrayals that provide deeper insights into the Iranian people. Aslānī refers to these types of documents in his films as “bayn-al-asnād” (between the documents), arguing that:

We must read between the lines of historical documents, recognizing that some remain unread or have been destroyed, and we must work to read everything lost or plundered. What has reached us may not be an authentic document. We have no genuine documents. Even a document indicating the time and place of a person passing by us during our conversation is not a true document, but a false one. For example, I need to read a document that captures their thoughts on what they have lost while wandering in the space between their home and the place of our conversation, in that very gap. My aim is not to present or validate a document, as is often done in some documentary films. There are documentary films that provide documents, and they are invaluable; I have no doubt about their significance, as they are useful and contribute to further analyses of the relevant topic. However, that is not my approach. I do not provide or discover documents […] Actually, in a society where authentic documentation has been lost and its collective wisdom and experiences distorted, we actively document ourselves as the past events and experiences, emphasizing their continuity in the present. Our collective memory as Iranians essentially becomes, in essence, a document, open to renewed readability, its readability is possible through my own perspective. For this reason, through my films, I appear, and I bring forth the collective memory of my land in the contemporary world.7Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, interview by Nematollah Fazeli and Mani Kalani in Chashm-andāzhā-yi farhang-i mu‛āsir-i Īrān, vol. 3 (Tehran: Pazhūhishgāh-i Farhang, Hunar va Irtibātāt, 2020), 204-205.

1.1. Aslānī’s Cinema about Iranian Stories: A Dramatic Documentary Cinema

Aslānī is a storyteller, sharing stories of the wisdom and experiences of Iranians throughout history. He achieves this in both his fictional films and those regarded as documentaries by film professionals, critics, and the public—a distinction he sees as blurred. When Aslānī says that creating a document means, “I use my films as a means to bring the shared history, experiences, and identity of my people into the present,” he is outlining his approach to documentary filmmaking. He believes that “documentary cinema will evolve towards storytelling, and we may no longer see mere documentaries […] that simply capture images of walls and doors.” This genre of documentary cinema, which Aslānī refers to as “dramatic documentary,” has notable examples such as Arba‛īn (1970) by Nāsir Taqvā’ī, an epic dramatic documentary.8Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, “Rāh-i nijāt-i sīnimā-yi Īrān rujū‛ bih mustanad ast,” Sharq Daily, December 6, 2016. Accessed March 22, 2025. https://www.magiran.com/article/3476232.

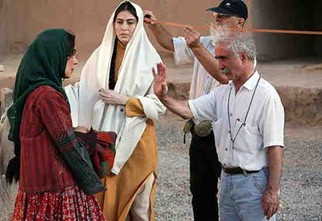

Figure 2: Muhammad Rizā Aslānī behind the scenes of The Green Fire (Ātash-i Sabz), 2008.

Some of Aslānī’s fictional films also reflect the unique storytelling and narrative-driven approach he uses in his documentaries. Take, for example, The Green Fire, which tells historical and documentary stories from the city of Kerman, beginning with its founding and including the story of the blinding of the young men of Kerman by the founder of the Qājār dynasty, Āqā Muhammad Khan Qājār, in 1794-95.9J. R. Perry, “Āḡā Moḥammad Khān Qājār,” Encyclopaedia Iranica Online, https://iranicaonline.org/articles/aga-mohammad-khan. These historical events serve as the backdrop for a love story between Nārdānah and Bahrām, whose struggle to stay together – throughout the historical eras of pre-Islamic and post-Islamic periods – is told up to the present day. Ultimately, by chance, they continue their passionate bond far from the historical setting of Kerman, fictionally (beyond a linear narrative) in a family court in contemporary Tehran.10The Green Fire, dir. Muhammad Rizā Aslānī (Iran: Kerman & Tehran, 2007), 00:83:30. It means that Aslānī’s films are not like Albert Lamorisse’s documentaries such as The Lovers’ Wind (1968). Aslānī believes that such documentaries “lack a proper dramatic perception when everything [the people, buildings, and nature] is viewed from above [by a helicopter].” No matter how beautiful, lively, and poetic those films are, or how much educational value they offer in terms of documentary film structure, to Aslānī they lack dramatic depth.11Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, “Rāh-i nijāt-i sīnimā-yi Īrān rujū‛ bih mustanad ast.” Sharq Daily, December 6, 2016. Accessed March 22, 2025. https://www.magiran.com/article/3476232.

Figure 3: A still from the film The Green Fire (Ātash-i Sabz), directed by Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, 2008.

Aslānī asserts that the term “poetic cinema” is a misnomer, advocating instead for the concept of “the poetry of cinema.” This poetry, he argues, is not conveyed through verbal expression—such as recited verse or narrated poetry in documentaries such as The Lovers’ Wind—but rather through “images [drawn from reality, a reality] that inherently manifests its poetic essence.” According to Aslānī, cinema—and by extension, his own films—have the potential to “discover the poetry of the world” through poetic imagery rather than poetic language.12Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, “Sīnimā’ī kih shi‛r-i-jahān rā kashf mīkunad.” Mehr News Agency, January 17, 2024. Accessed March 22, 2025. https://www.mehrnews.com/news/5997319.

In tracking reality through poetic imagery, his films set in cities such as Kerman, Hamedan, and Tehran allow audiences to grasp the essence of these urban spaces through Aslānī’s cinematic lens. For instance, in the film Tehran: Conceptual Art (Tehran: Hunar-i Mafhūmī, 2012), the reality of Tehran becomes a subject of artistic exploration through the poetic images reflected on the glass of boutiques and car windows, capturing the city’s essence.

Figure 4: Poster for the film Child and Exploitation (Kūdak va Istismār), directed by Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, 1982.

Also, the tragic/heroic reality of motifs, engraved on the Hasanlū Cup is explored in the short film Hassanlou Cup: The Tale of the One Who Asks (Jām-i Hasanlū, 1964). Similarly, poetic imagery is employed to depict the harsh or sorrowful realities of children subjected to oppression and violence in films such as Badbadah: The Story of the Boy Who Asks, and Child and Exploitation (Kūdak va Istismār, 1982). Poetic imagery is also used to depict the realities of issues and challenges that have persisted since the establishment of Bank Millī of Iran, as seen in the film Memoirs of a 75-Year-Old Man (Khātirāt-i yak 75 sālah, 2007). One such image features a female employee at Bank Millī, wearing a pūshīyah—the traditional full-face veil worn by Iranian women in the late Qājār era—sitting behind a computer in one of the bank’s modern branches, working diligently. She represents the women Aslānī references in other scenes: those who, after the Constitutional Revolution, helped provide the initial capital for Bank Millī by selling their jewelry.13Memoirs of a 75-Year-Old Man, dir. Muhammad Rizā Aslānī (Iran: Tehran, 2007), 00:15:11.

Figure 5: Muhammad Rizā Aslānī with the Hasanlū Cup in 2016, fifty years after creating Hassanlou Cup: The Tale of the One Who Asks (Jām-i Hasanlū), 1966.

Therefore, through various storytelling techniques in his films, Aslānī offers a unique approach to exploring historical phenomena that may not be directly tied to contemporary world issues. In some of his works, he examines the origins of old cities, ethnic rituals, or ancient artifacts. For example, in the films The Green Fire (2008) and The Hands of Hegmataneh (Dast-hā-yi Higmatānah, 2010-12), Aslānī narrates many events that have shaped Kerman and Hamedan from their beginnings to the present day. However, rather than following a linear progression from past to present, he adopts a cyclical approach, moving between past and future in a way that surprises the audience. The audience will be surprised, as they may expect a documentary-style historical narrative based on research that traces the key events that have shaped these cities over time. Instead, it is at times difficult to determine whether the stories about these cities are entirely factual. The audience can encounter Aslānī’s creative imagination, which is reflected in how he:

- either speaks about these cities and his feelings toward the hardships and suffering endured by their people,

- or addresses the cultural heritage passed down from previous generations to the contemporary audience of his films,

by incorporating poetic verses or lyrical statements woven into the film’s background narration, featuring poetic reflections on the cultural heritage and handicrafts of Hamedan, such the pottery made in the city of Lalahjīn.

So, to clearly illustrate how Aslānī, through the narrator’s voice, simultaneously presents:

- Both reality and his imagination regarding the hardships endured by the people of these lands,

- Both the past and the future of these cities, and

- Both the tradition of cultural heritage and its process of modernizing.

It is necessary to include an excerpt from Aslānī’s narration in the film The Hands of Hegmataneh to further illustrate this point:

These Kassite ancestors, from northern Khurāsān to Higmatānah, they live still, even now, in the hands of mine, [the potter]; I am gripped by a terrible, sleepless fear—how carry this delicate heir—born of generations of artistry—into a present too blind to the future it might shape. […] This is no mere craft; it is a trust. […] My hands press into the clay, grasping every pattern, feeling every texture. I sense them and hear the echoes of centuries. I see them moving—century by century—backward into the past and forward into the future, until they stand beside me. They murmur to me—echoing their hopes, despairs, and joys—yearning to break free, to be remembered, to step into the light from the depths of isolation and obscurity.14Hands of Hegmataneh, dir. Muhammad Rizā Aslānī (Iran: Hamedan & Tehran, 2010–12), 00:43:30.

Figure 6: A still from the film The Hands of Hegmataneh (Dast-hā-yi Higmatānah), directed by Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, 2010-2012.

At the end of this section, it is once again emphasized that Aslānī’s documentary cinema does not focus on describing verifiably historical events related to objects, people, cities, or social and historical institutions. With this perspective on dramatic documentary cinema, Aslānī selects the themes and concepts for both his fiction and nonfiction films to further his innovative explorations of cities, ancient artifacts, and administrative institutions.

1.2. Conceptual structure of article

Despite Aslānī’s enduring approach over more than half a century of filmmaking—one that blends storytelling with historical and documentary elements—his cinematic works exhibit a dynamic creative process in both form and content. This process allows his films to be classified into three configurations:

- a) Archaicism,

- b) Formalist Critique,

- c) Harsh Realism.

In the years leading up to the 1979 Revolution, Aslānī explored a stark and unflinching realism in depicting human suffering and deprivation, particularly in his feature film Chess of the Wind and the short film Badbadah: The Story of the Boy Who Asks. At the same time, in the short documentary-style film Hassanlou Cup: The Tale of the One Who Asks and the television series Samak the ‛Ayyār and Abū Rayhān Bīrūnī (1975), the question of tradition and its reproduction (following a historic sensibility) became a central theme in his cinematic vision. This intellectual and cinematic inquiry continued in the years following the revolution.

While Aslānī’s work often features formalist critique, artistic freedom, and avant-garde imagery, these elements take on a distinct and independent form—from the other configurations of historicity and realism—in Tehran: Conceptual Art. This artistic approach sets the film apart as a significant and singular piece within Aslānī’s body of work. This work will be discussed in the second section of the article, where Aslānī’s techniques and perspective on reality—captured through his camera—will be examined to create a framework for explaining his ideas. Therefore, before examining the main themes of Aslānī’s cinema and his approach to dramatic documentary filmmaking, it is important to first explore his core principles and ideas. So, in the second part of the article, we examine Aslānī’s filmmaking ideas through a theoretical analysis of Tehran: Conceptual Art. Then, using his theoretical framework, we refer to Aslānī’s understanding of Ferdinand de Saussure’s semiotic theories to explain how reality is presented in his films.

The methodology section (Part Three) examines a key theme in Aslānī’s cinema, “universal intelligence,” which represents the core thesis of his filmmaking.15See the dialogue between Nārdānah and Kanīzak (Servant) in The Green Fire, dir. Muhammad Rizā Aslānī (Iran: Kerman & Tehran, 2007), 00:95:00. Part Four then explores its antithesis, “mournful, and murderous modernity.”16Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, Dīgarkhānī-i Sīnimā-yi Mustanad (Tehran: The Documentary and Experimental Film Center, 2015), 59. By selecting these two films, The Green Fire and Chess of the Wind, we highlight the two main stylistic approaches in Aslānī’s cinema: A synthesis of historical tradition and a revitalized tradition in The Green Fire, reflecting the theme of “universal intelligence,” and a harsh, horrified and unsettling realism that drives the cinematic narrative of Chess of the Wind. The two mentioned films, besides Tehran: A Conceptual Art analyzed in detail below, fall under the category of dramatic documentary cinema.

In Part Five of this article, the synthesis of these two theses will be examined—considering how the filmmaker’s contrasting perspectives before and after the 1979 Revolution can be brought into balance. How can these two contrasting approaches in Aslānī’s engagement with reality—explored in detail in Parts Three and Four—be reconciled into a balanced form? This contradiction can be resolved if audiences and critics of Aslānī’s films try to “discover beauty” in understanding his works, as he himself puts it.17‛Alī Ranjī Pūr, “Az pīchīdagī-i jahān bih zībā’ī-shināsī-i Tihrān: Guftugū bā Muhammad Rizā Aslānī,” Insān-shināsī va Farhang, January 3, 2014, http://bit.ly/49oz04b. As a result, three of Aslānī’s signature films, Tehran: Conceptual Art, The Green Fire, and Chess of the Wind, are examined in detail in this article.

- A theoretical framework for analyzing Aslānī’s cinema; A case study of Tehran: Conceptual Art

Aslānī, through the strategies of “shifting position” and “repositioning”18Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, Dīgarkhānī-i Sīnimā-yi Mustanad (Tehran: The Documentary and Experimental Film Center, 2015), 23. the subjects of his films—ranging from Bank Millī and Tarbīyat-i Mudarris University to the Hasanlū Cup and the city of Tehran—by challenging conventional perceptions, invites his audience to reengage with realities of Tehran, Bank Millī, and the Hasanlū Cup. He presents Tehran, Hasanlū Cup, and a particular aspect of Bank Millī as something entirely different from what we have previously known.

From Aslānī’s point of view, reality is constituted through “becoming” and “movement.”19Regarding “movement,” Aslānī writes: “Reality, or the real, unfolds through movement—it takes place, happens, and becomes real in the moment of its actuality.” See Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, Dīgarkhānī-i Sīnimā-yi Mustanad (Tehran: The Documentary and Experimental Film Center, 2015), 30. Accordingly, as the camera moves, the audience’s perception of reality—such as that of a street in Tehran—undergoes a transformation. Aslānī uses filmmaking techniques that are fundamental to cinema, particularly by making the camera move in a way that simulates how people naturally shift their look in everyday life. This reflects how individuals constantly change their sight when looking at buildings, people, objects, and even their bodies in an urban setting. Through this approach, he aims to portray urban reality as fluid and ever-changing, challenging any fixed perception about the reality of city.

In the case of Tehran, he depicts the city as inherently unstable and in a constant state of flux. In other words, the camera’s movement, along with recitations of poetry (that do not directly explain the reality of Tehran), invites the audience into a state of imagination, showing that imagining something is, in itself, part of the reality of something. In this sense, Aslānī’s depiction of Tehran emerges through the reflections of its streets, buildings, cars, and citizens on glass surfaces, such as the windows of boutiques, cars, and buses.20For the shots of boutiques, cars, and bus windows, see Tehran: A Conceptual Art, dir. Muhammad Rizā Aslānī (Iran: Tehran, 2012), 00:13:48, 00:19:30, 00:23:19, 00:03:04, 00:04:06, 00:23:19. By creating such conditions, the audience may, intentionally or unintentionally, be prompted to question what Tehran’s reality would be in the absence of its streets: is it the poems recited by the narrator in the film, or the voice of Rūshanak (1935-2012) in the Gulhā program on Radio Iran? Or is it nostalgic images of old Tehran and its Tūpkhānah Square? Or the ancient artifacts in the National Museum of Iran (mūzah-yi millī-i Īrān)? Or is it the modern art sculptures installed in the outdoor area of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art (mūzah-yi hunarhā-yi mu‛āsir-i Tihrān)?21For all the shots and scenes depicting the aforementioned elements, see Tehran: A Conceptual Art, dir. Muhammad Rizā Aslānī (Iran: Tehran, 2012), 00:03:04, 00:04:06, 00:07:52, 00:08:29, 00:18:05, 00:19:30, 00:22:06, 00:23:19, 00:24:10, 00:26:00, 00:29:37, 00:31:09, 00:31:20, 00:32:48, 00:38:19, 00:43:23, 00:49:26, 00:64:31. The last two are filmed directly, without reflecting historical objects on glass surfaces. Therefore, imagining what Tehran was in the past or what the realities of this city would become in the future are also part of Tehran’s reality, especially since, from Aslānī’s perspective, “reality = becoming, not being.”22Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, Dīgarkhānī-i Sīnimā-yi Mustanad (Tehran: The Documentary and Experimental Film Center, 2015), 29.

In summary, it can be noted that based on this understanding of reality, Aslānī presents Tehran’s reality to be as dynamic, diverse, and multifaceted in the film Tehran: Conceptual Art. This depiction about the reality of Tehran can include poems about the city, imaging its buildings and urban facades as ruins (because seen as distorted images caused by reflections on glass), and the recreation of that charming solitude of old Tehran. In other words, Aslānī seeks to express reality in a way that breaks from fixed reality through his films such as Chīgh (1996), and others depicting Bank Millī, Hasanlū Cup, Tehran, Hamedan Kerman, and Tarbīyat-i Mudarris University; by “freeing”23Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, Dīgarkhānī-i Sīnimā-yi Mustanad (Tehran: The Documentary and Experimental Film Center, 2015), 97-98. Tehran, Hamedan, and Hasanlū Cup from the singular true reality imposed upon them.

Figure 7: A still from the film Chīgh, directed by Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, 1996.

With this understanding of reality in Aslānī’s works, we can now gain a clearer insight into how he visualizes his central theme, “universal intelligence,” in one of his most prominent films, The Green Fire, and the cinematic techniques he employs to represent it. This raises the question of how he creates the images that represent this theme in his works. In addressing this methodological question, particularly in relation to the film The Green Fire, one could argue that if the cosmos—or the world itself—possesses intelligence, then, by extension, cities such as Kerman, Tehran, and Hamedan also embody a distinct form of intelligence and insight. This suggests that the very fabric of these cities, much like that of the universe, is interwoven with an inherent consciousness embedded within them, waiting to be recognized and understood.

- Analysis of the theme of “universal intelligence” (as a thesis) in The Green Fire

The supposed engaged audiences understand “universal intelligence” when they experience Tehran’s reality presented in different forms—such as poetry, ancient artifacts, and old images of the city—and recognize its transformation. They connect with certain elements of the film, such as the reflections of Tehran on bus windows, while feeling less emotionally or intellectually engaged with other aspects, such as the recited poems, which seem more distant or harder to relate to. Aslānī explains this dynamic of proximity and distance between the audience and the realities of Tehran using the semiotic concepts of signifier and signified. Simply put, when the audience derives profound pleasure from Rūshanak’s voice, it signifies the union of the lover and the beloved.24Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, Dīgarkhānī-i Sīnimā-yi Mustanad (Tehran: The Documentary and Experimental Film Center, 2015), 57. Conversely, when the film becomes tiresome or boring, it reflects a state of estrangement between them—Tehran, in this case, being the beloved.

Similarly, focusing on Aslānī’s The Green Fire in a semiotic analysis, Kerman’s transformation parallels the lovers’ separation—Nārdānah and Bahrām as Laylī and Majnūn—symbolizing the city’s reality. In this state of distance and parting, Aslānī expands upon Saussure’s notion of signifier and signified. There is no separation between “Majnūn [Bahrām] = signifier” and “Laylī [Nārdānah] = signified,” much like “the two sides of a single sheet of paper.”25Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, Dīgarkhānī-i Sīnimā-yi Mustanad (Tehran: The Documentary and Experimental Film Center, 2015), 57. Thus, the reality of Kerman, across various historical periods, undergoes a transformation towards the unification of “the self and the non-self,” embodied by Bahrām and Nārdānah.26Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, Dīgarkhānī-i Sīnimā-yi Mustanad (Tehran: The Documentary and Experimental Film Center, 2015), 198. However, this union is disrupted before the film’s conclusion due to the betrayal of a maid, a rival to Nārdānah’s faithful love for Bahrām. Despite receiving food and water from Nārdānah, she betrays her out of vileness and disloyalty. The story unfolds as Nārdānah encounters Bahrām, who has been struck by seven arrows and perished. Each day, she must remove one arrow from his body so that he may come back to life and ultimately reunite with her. After Nārdānah has removed six arrows, the maid takes the final one, knowing that whoever removes the last arrow will awaken Bahrām and become his wife. As a result, the once-poor servant girl rises to a position of wealth and status in Bahrām’s noble household.27The Green Fire, dir. Muhammad Rizā Aslānī (Iran: Tehran, Kerman, 2007), 00:14:00, 00:77:30.

Figure 8: A still from the film The Green Fire (Ātash-i Sabz), directed by Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, 2008.

On this basis, among the themes of the film The Green Fire, the masculine signifiers of Bahrām’s embodiment who ultimately does not reach his beloved Nārdānah—though he gradually moves toward union with her—include the following elements:

Lutf-’Alī Khan Zand, who was besieged in the city of Kerman and blinded by Āqā Muhammad Khan Qājār, and Mushtāq-‛Alī Shah, who sang the Quran to the tune of a sitār and was stoned to death by the city’s religious fanatics, are both signifiers of the city of Kerman’s failure, reflecting Bahrām’s ultimate failure to reach his beloved Nārdānah.28The Green Fire, dir. Muhammad Rizā Aslānī (Iran: Tehran, Kerman, 2007), 00:56:00. Another case is the maid’s desire, which, as noted by Aslānī, symbolizes Nārdānah’s “base desire.”29Alī Rizā Hasanzādah, “Guftugū bā Muhammadrizā Aslānī: Afsānah-hā-yi Īrānī va sīnimā-yi mustanad va ā’īnī,” Vista. Accessed March 22, 2025. https://vista.ir/w/a/21/7ax5v. Her failure to fulfill her romantic duty of caring for Bahrām ultimately results in her separation from him. Thus, all these signifiers are the signifiers of separation, distance, and absence, which unfold within the context of the reality of the city of Kerman, as narrated by Aslānī. However, this drifting apart does not embody “universal intelligence,” which is another facet of the reality of Kerman that is “reality = becoming, not being.”30Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, Dīgarkhānī-i Sīnimā-yi Mustanad (Tehran: The Documentary and Experimental Film Center, 2015), 29. “Universal intelligence” is that signified of “love and union,” which, beneath all signifiers of alienation and separation, remains “silent”, yet “flows” in motion.31For more on the theme of love and union: The Green Fire, dir. Muhammad Rizā Aslānī (Iran: Tehran, Kerman, 2007), 00:84:00. Love is fluid, a constant “becoming,” drawing Bahrām and Nārdānah toward one another, particularly when Bahrām defends the legitimacy of his marriage to Nārdānah in a contemporary Tehran civil court, stating:

“[…] Neither death is a tale, nor life. When union occurs, the beloved is reached, love is present, and in that moment, we exist. We are all here.”32The Green Fire, dir. Muhammad Rizā Aslānī (Iran: Tehran, Kerman, 2007), 00:84:00.

Thus, anyone who challenges the “universal intelligence,” the union between the beloved and the becoming of humanity toward dignity, will be humbled by this intelligence and falter—much like the people of Kerman, who, due to their silence or complicity, failed during the stoning of Mushtāq ‘Alī Shah in 1791, just three years before Kerman fell to the forces of Āqā Muhammad Khan Qājār. The passivity or complicity in the crime erodes their collective spirit of unity and mutual support, leaving them vulnerable to collapse following the conquest of Kerman by Āqā Muhammad Khan, who blinded the city’s inhabitants.33The Green Fire, dir. Muhammad Rizā Aslānī (Iran: Tehran, Kerman, 2007), 00:98:00. Nārdānah’s parents, too, were brought down by “universal intelligence,” for they failed to comprehend Nārdānah’s love for Bahrām, so, in their legal complaint at court, no ruling was made in their favor.34The Green Fire, dir. Muhammad Rizā Aslānī (Iran: Tehran, Kerman, 2007), 00:68:30. Similarly, the maid sees herself in a distorted, grotesque form in the mirror that Bahrām bought for her, and in the final scene of the film, she falls from grace.35The Green Fire, dir. Muhammad Rizā Aslānī (Iran: Tehran, Kerman, 2007), 00:98:00. In the scene before her descent, Nārdānah warns her, and the following conversation ensues:

Maid: I might have made a mistake in my choice [choosing Bahrām and removing the last arrow from his body], and indeed, I did surely, [but a mistake like] this should not end in such torment.

Nārdānah: This is not torment; it is a trial, an experience. Perhaps a deeper experience. A vast circle exists, drawing you and me into its fold, compelling us to carry [the world with us.] […] It is our fragile hands that bear the world’s trust. This is both suffering and joy, both fulfillment and the price it demands.

Maid: No! I am not of this world. Why should the world not bear my burden? Why should the world condemn me to experience? […] Why shouldn’t I subject the world to experience myself? To a trial?

Nārdānah: This is perilous for both of us. To undertake such a thing, one must be elsewhere, endowed with a different kind of intelligence.

Maid: What kind of intelligence? Another kind? The intelligence to know the entire world? For what purpose? Why? No! I will not trade my own intelligence for a universal intelligence, one that is not mine.

Nārdānah: This is your choice—to battle against universal intelligence. And so, you will fall. You will be subjected to…

Maid: To what?

Nārdānah: To confession.36The Green Fire, dir. Muhammad Rizā Aslānī (Iran: Tehran, Kerman, 2007), 00:92:30.

Thus, the maid who betrays Nārdānah and covets Bahrām’s possessions falls into conflict with the “universal intelligence.” The very notion of being a maid and servant while simultaneously being the wealthy Bahrām’s wife had already been explored in Aslānī’s cinema years before The Green Fire, in his film Chess of the Wind. In that film, too, a maid and an aristocratic lady, who is paralyzed and confined to a wheelchair, in a manor house in Tehran, are driven to confess to the murders, including that of the lady’s tyrannical stepfather, with the complicity of the men involved in their crime. They witness the consequences of their actions and descend into depravity one by one. On the women’s side of the murder, the aristocratic lady’s fall from her wheelchair serves as an allegory for her moral descent into confession. Symbolically, she dies both before and after killing her stepfather.37Chess of the Wind, dir. Muhammad Rizā Aslānī (Iran: Tehran, 1976), 00:82:19. Moreover, these women killing the traditionalist stepfather serves as a metaphor for modernity’s massacre of tradition. While in The Green Fire, the “universal intelligence” holds a determining position as the main thesis and key axis of the work, in Chess of the Wind, modernity and human intelligence, which ensnares Tehran and Iran, serve as an antithesis.

Years after Chess of the Wind, Aslānī introduced a conceptual expression he called “the killer modernity” in his book Rereading Documentary Cinema (Digarkhānī-i Sīnimā-yi Mustanad, 2015).38Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, Dīgarkhānī-i Sīnimā-yi Mustanad (Tehran: The Documentary and Experimental Film Center, 2015), 59. After the re-release of Chess of the Wind on the international stage and its reception by critics at the 2020 Cannes Film Festival, an Iranian anthropologist and a film scholar of Aslānī’s works, Nāsir Fakūhī, employs phrases similar to “killer modernity” when describing a sorrowful, melancholic modernity imbued with a sense of hatred and vengeance. He analyzes the manifestations of this vengeful ‘killer modernity’ in the film Chess of the Wind.

From Fakūhī’s perspective, the antithesis of “universal intelligence,”—modernity in Iran—manifests as a form of desire to modernity that unleashes a destructive energy, allowing the oppressed and tormented women to take blind revenge on men. The maid in The Green Fire does not possess such power and confesses her wrongdoing, but the maid and the aristocratic lady in Chess of the Wind seem to represent “a vengeful modernity that is alive yet melancholic, perhaps leaving [these women] with nothing of modernity except feelings of hatred and revenge.” In Aslani’s narration of Iranian modernity, “he does not question whether modernity is legitimate, whether it should be accepted, or which social class or group benefits from it [women or men.] Instead, he seeks to give modernity a visual-cinematic, and material embodiment—such as womanhood, disability, and a wheelchair.”39Nāsir Fakūhī, “Tūfān-i sunnat va taʿlīq-i mudirnītah,” Insān-shināsī va farhang, February 8, 2021. Accessed March 22, 2025. https://bit.ly/3Tf5yHB.

Figure 9: Khānūm Kūchak (Fakhrī Khurvash), a paralyzed woman in a wheelchair inside a manor house in Tehran. A still from the film Chess of the Wind (Shatranj-i Bād), directed by Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, 1976.

Since Aslānī’s intention is not to propose or expand theoretical ideas about modernity and its legitimacy, our article, similarly, does not aim to provide a theoretical understanding of modernity. Rather, the focus is solely on analyzing the instances of “killer modernity”—a modernity imbued with feelings of vengeance and hatred—which serves as the antithesis to the theme of “universal intelligence,” as portrayed in the film Chess of the Wind.

Therefore, before turning to section 5 of this article, in which I will examine the confrontation, interaction, and clash of the thesis and antithesis—namely, “universal intelligence” and “killer modernity” (or vengeful and melancholic modernity), in the next section it is important to note that we will analyze Aslānī’s portrayal of the theme of “killer modernity” as it is depicted in the film Chess of the Wind, rather than as the concept of modernity experienced in Iran.

- Analysis of the theme of “killer modernity” (as an antithesis) in Chess of the Wind

In his later films, Aslānī portrays the world—including cities and romantic relationships—as dynamic and ever-evolving aspects of his exploration of reality. This is exemplified by Bahrām and Nārdānah on their path towards union, as well as by the shapeless, multifaceted city of Tehran. In contrast, his earlier works—particularly Chess of the Wind—portray a world that resists this “becoming” and dynamic evolution and, in doing so leads to catastrophe.

Chess of the Wind can be classified as a crime genre film, engaging the audience with excitement and anxiety. But especially, following the discovery of its lost original version—restored in high quality by the Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project and Cineteca di Bologna at L’Image Retrouvée laboratory (Paris)—and its positive reception at the 2020 Cannes Film Festival, this continued interest and public acclaim, even after half a century, indicate that the film contains deeper conceptual layers beyond a mere crime story. These layers reflect a depiction of an insecure and unstable world, a consequence of the failed reforms of the Constitutional Revolution and the thwarted revisionism of Iranian intellectual. The film portrays this insecure world through a narrative set in the final years of the Qājār dynasty. This unstable world came to an end during the first and second Pahlavī periods, amidst Iran’s modernization and industrialization, which upended the country’s traditional order. It is portrayed by a dramatic focus on the character of Khānūm Kūchak:

A paralyzed aristocratic woman conspires with her maid—who is also her companion and lover40Chess of the Wind, dir. Muhammad Rizā Aslānī (Iran: Tehran, 1976), 00:61:00. —to murder her stepfather, Atābak. Khānūm Kūchak ultimately dies as part of the maid’s plot, who shares the plan to murder Atābak with her.41Chess of the Wind, dir. Muhammad Rizā Aslānī (Iran: Tehran, 1976), 00:35:40. Despite this relationship, the maid’s ultimate goal, in collaboration with one of Atābak’s nephews, was to murder Khānūm Kūchak and seize her maternal inheritance because Atābak, a man of the bazaar who appears religious and traditional but is, in fact, foul-mouthed and lustful in sexual desire to maid, had secretly transferred the estate of Khānūm Kūchak’s deceased mother into his own name.42Chess of the Wind, dir. Muhammad Rizā Aslānī (Iran: Tehran, 1976), 00:04:35. Meanwhile, Atābak’s nephew, Sha‛bān, a nouveau riche and pretentious intellectual figure, was in league with the maid. Having promised her marriage, he intended to kill both his uncle and Khānūm Kūchak in order to use the wealth from her mother’s estate to establish factories, thereby reviving their aristocratic lineage under the guise of industrialism and capitalism.43Chess of the Wind, dir. Muhammad Rizā Aslānī (Iran: Tehran, 1976), 00:91:00. The other nephew, on the other hand, sought to marry Khānūm Kūchak and, after his uncle’s murder, attempted to rent out their manor house to the English for speculative and unproductive activities, in a bid to generate effortless income by renting out the property.

While in many of Aslānī’s films we encounter a dreamy world, a reality that is evolving and transforming, and a journey towards unity, connection, and love, the other side of Aslānī’s cinematic universe is harsh, overly realistic, and based on events that he had read about or personally experienced—mainly from the 1950s to the 1970s. This side is ultimately reflected in Chess of the Wind.

Figure 10: Shuhrah Āghdāshlū, as the maid, in a still from the film Chess of the Wind (Shatranj-i Bād), directed by Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, 1976.

Throughout his half-century career in filmmaking following Chess of the Wind, Aslānī rarely portrayed the harsh, tragic, and dramatic fate of modernism and the process of modernization in Iran during the late Qājār and Pahlavī eras with such intensity again. He framed the game of Chess of the Wind with feminine and masculine-coded winds: winds with white and black pieces on a chessboard. The chessboard was set in Khānūm Kūchak’s house, with pieces representing white-clad women who are modern yet frail, weak, sick, lesbian sensuality, loveless, and murderous, as well as black-clad, traditionalist men who are also traditional, lustful and murderous; this is a chess game between the world of traditionalists and that of modernists.

Aslānī soon distanced himself from Chess of the Wind and transitioned into a new phase of filmmaking, one that delved into themes such as “universal intelligence,” existence, union, and love. Over the subsequent fifty years of his professional career, he refrained from revisiting the themes of Chess of the Wind, as he believed the film had already encapsulated everything the industrial world could lead to at its endpoint. From his point of view “in modernity, the signs [of these masculine and feminine-coded winds] were massacred;”44Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, Dīgarkhānī-i Sīnimā-yi Mustanad (Tehran: The Documentary and Experimental Film Center, 2015), 59. figures such as the maid, Atābak, and Khānūm Kūchak. In this film, the idea that “those who sow the wind reap the storm” is central, suggesting that anyone who repeats such actions in the modern world will inevitably face the same destructive consequences. The film dismantles the false chess game between pieces of traditionalism and modernism, and the ideas representing both sides were finally eradicated. By moving beyond the repetitive themes of tradition versus modernity, Aslānī shifted his focus towards exploring the concept of “universal intelligence.”

Due to its criminal themes, mysteries, and the sense of fear it evokes in the audience—such as through Atābak, who, despite appearing to be killed by Khānūm Kūchak, is later shown to be alive and engaging in lustful acts with the maid in the bathhouse45Chess of the Wind, dir. Muhammad Rizā Aslānī (Iran: Tehran, 1976), 00:85:23. —Chess of the Wind can also be classified as a film with a suspenseful and horror-driven narrative. However, it is not that simple. In the final scene—after the deaths of Khānūm Kūchak, Atābak, and the nephew (Sha‛bān)—the maid frees herself from this game of chess and decides to leave the house, which is filled with crime and fear, especially after her own failed murder plot. From the graceful figure of a charming, heart-stealing girl, she emerges—draping a chador over her head—and as the melodious call to morning prayer fills the air, she steps out of the house, taking the path through the beautiful garden-lined alley across the street.46Chess of the Wind, dir. Muhammad Rizā Aslānī (Iran: Tehran, 1976), 00:96:28.

Figure 11: A still from the film Chess of the Wind (Shatranj-i Bād), directed by Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, 1976.

Figure 12: A still from the film Chess of the Wind (Shatranj-i Bād), directed by Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, 1976.

In a paradoxical manner, despite the chador’s dark hue and the prevailing sense of alienation in the urban landscape, the maid’s liberation from the manor house, allowing her to walk freely in the city, coupled with the beauty and greenery of the alley, anticipates a vision of the future for many traditional women in the years following the 1979 Revolution. Women, in a paradoxical manner, submitted to all the restrictions imposed upon them following the revolution, while simultaneously finding opportunities for progress, employment, and education outside the home.

This sense of freedom becomes increasingly evident as the camera gradually distances itself from the veiled maid and the manor house of the late Qājār era, ascending to greater heights. Through its movement and cinematographic focus on the Plasco Building—a symbol of mid-Pahlavī modernist architecture—it articulates the trajectory of Tehran’s urbanization and transformation. This emphasis becomes even more pronounced when the camera comes to a halt in front of the Sāmān Twin Towers and the former Ministry of Agriculture building—modern structures from the late Pahlavī era—further reinforcing the narrative of Tehran’s transformation.47Chess of the Wind, dir. Muhammad Rizā Aslānī (Iran: Tehran, 1976), 00:99:00. Thus, the film concludes with shots that depict the telos of modernization at the time as the expansion of Tehran towards the northern part of the city. The call to dawn prayer, too, gets lost in the clamor of car engines. It seems that, at the end of the film, following all the violence, Aslānī elegantly captures a sense of void, weightlessness and flight; Beauties that evoke alternate realities that might exist within this city.

In other words, in the final sequence of Chess of the Wind, the architecture of the urban space around Lālahzār Street and Firdawsī Square—featuring old yet beautiful buildings from the late Qājār and early Pahlavī periods—the beauty of the call to prayer, the flight of pigeons around the swamp coolers on the gabled roofs, and the tranquil solitude of early morning Tehran all merge to create a distinct atmosphere. This moment signals Aslānī’s vision of his future work, namely the film Tehran: Conceptual Art.

The contradictions of Tehran for the maid are revealed in this final scene of the film, which shows that this ostensibly beautiful and serene city is, in fact, constructed upon the suffering and pain of women. Through the departure from the house laden with violence and the tower crane camera shots, Aslānī endeavors to emancipate the maid, and symbolically all women, from their hardships at the dawn of a new, modernized city. This is where the recitation of Surah Al-Takāsur at the beginning of the film becomes meaningful:

It busied you with waging war against one another in multitudes,

until you counted the dead in their graves.

No, it must not be — no, never — to be distracted from the path of deliverance.

No, no, no — indeed, awaken, and be aware!48The film uses the Persian translation of the Surah Al-Takāsur by Abu al-Fazl Rashīd al-Dīn Maybudī, a 12th century Persian scholar, theologian, and commentator on the Quran. See Chess of the Wind, dir. Muhammad Rizā Aslānī (Iran: Tehran, 1976), 00:03:36.

The path to salvation here is the very reality of the city of Tehran and its beauties, which Aslānī later explores in Tehran: Conceptual Art.

- In quest of beauty; The synthesis of peace and wisdom (thesis) and hatred and anger (antithesis) as the aesthetic pursuit

The audience’s engagement with Aslānī’s cinema is deeply creative. This means that, based on the discussions outlined in the introduction and his three main filmmaking approaches (archaicism, formalist critique, and harsh realism), viewers—especially of his later works, such as Tehran: Conceptual Art and The Green Fire—have more freedom to interpret the films in their own ways, in betweenness of peace and wisdom (thesis) and bitterness and realism (antithesis). But how do viewers gain such freedom? The answer lies in Aslānī’s innovations in form, which continually engage the audience by maintaining a sense of suspense. He skillfully avoids an overemphasis on traditional Iranian customs, while simultaneously allowing viewers to retain a sense of optimism towards the beauty of the world, despite the bitterness and disillusionment present in contemporary global realities. Aslānī calls on us to liberate ourselves from the terrifying game of chess by seeking and discovering beauty in the world, thereby becoming conscious of the unending wars and the pervasive exploitation and oppression in the contemporary world. He writes:

Releasing more than six billion codes—thirsty codes, yearning to reveal their infinite poetic potential amid poverty, oppression, invisibility, absence, and the humiliation imposed by chains that bind them—[to express] their boundless capacity for freedom, a potential that resides in the mind of God […].49Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, Dīgarkhānī-i Sīnimā-yi Mustanad (Tehran: The Documentary and Experimental Film Center, 2015), 59, 97. [Yet] in modernity, the signs of [this poetic nature and desire for liberation] were obliterated.50Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, Dīgarkhānī-i Sīnimā-yi Mustanad (Tehran: The Documentary and Experimental Film Center, 2015), 59.

Humans, from the maid to Nārdānah and Bahrām, possess the capacity to find beauty, a beauty that belongs to God. Or more precisely, it could be said that beauty is “universal intelligence,” as previously mentioned. Beauty, in this context, is “a reality = becoming.” From Aslānī’s perspective, beauty is an inherent potential or quality that exists within the mind of God; beauty is “universal intelligence,” or a reality embodied in cities like Tehran or Kerman, which transforms into a thousand different forms. The ultimate manifestation of this multifaceted beauty, and the ultimate purpose of this ever-evolving reality, is becoming—a becoming that aims toward the union of Nārdānah and Bahrām. The telos of becoming is also the connection of the city’s inhabitants with “public spaces” and providing them the opportunity to pause in the city’s “sidewalks” and “squares” in order “to find and see each other.” To this end, at the conclusion of Chess of the Wind, the camera optimistically focuses on the city’s newer buildings. Aslānī later invites his audience to encounter one another and explore the beauties of the National Museum of Iran or the Museum of Contemporary Art in Tehran—public spaces of the city.

Thus, “universal intelligence” helps Aslānī’s audience, who are in search of beauty, to attain freedom. By portraying beauty as “aesthetic rapture,” Aslānī aims to empower his audience to transition from the “reality [of Tehran] to its metaphorical image [like reflection on glass and the poetry describing the city].”51‛Alī Ranjī Pūr, “Az pīchīdagī-i jahān bih zībā’ī-shināsī-i Tihrān: Guftugū bā Muhammad Rizā Aslānī,” Insān-shināsī va Farhang, January 3, 2014. Accessed March 22, 2025. http://bit.ly/49oz04b. Thus, he liberates his audience’s imagination, allowing them to explore other potentials of the city. This constitutes a form of freedom through aesthetic experience, enabling them to uncover a beauty that has been concealed from them. Aslānī aims to free his audience from the harsh realities of the cities they live in and the institutions that negatively affect their lives and trap them. He seeks to rescue his audience from a killer modernity in cities such as Tehran, Hamedan, Kerman, and even at institutions such as Tarbīyat-i Mudarris University and Bank Millī. He believes they can be saved if they are able to perceive beauty in an alternate reality of Tehran—whether in the reflections of the city on its glass facades, the tranquility of its early morning, or in the romantic beauty of Nārdānah and Bahrām’s struggle to unite. Aslānī’s cinema is aesthetically profound, inviting us to uncover distinct forms of aesthetics that go beyond the conventional and ordinary beauty.

Cite this article

This article explores the cinematic philosophy of Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, focusing on his unique integration of poetry, visual aesthetics, and documentary realism within Iranian cinema. Through an analysis of key works, including Shams-e Tabrizi and The Chess Game of the Wind, the article investigates how Aslānī constructs a lyrical mode of storytelling that blurs the boundary between the real and the imagined. Drawing on theories of poetic realism, phenomenology, and post-revolutionary aesthetics, the study positions Aslānī as a filmmaker whose work resists dominant cinematic conventions by infusing his films with mysticism, historical memory, and symbolic fragmentation. The article argues that Aslānī’s cinema is not merely a reflection of reality but a reinterpretation of it—rendered through poetic form, cultural allegory, and philosophical depth. In doing so, it redefines the potential of Iranian cinema as a medium for intellectual and aesthetic innovation.